An Exploration of Social Systems As Informative for Urban Regeneration in Potchefstroom Central Business District

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Early History of South Africa

THE EARLY HISTORY OF SOUTH AFRICA EVOLUTION OF AFRICAN SOCIETIES . .3 SOUTH AFRICA: THE EARLY INHABITANTS . .5 THE KHOISAN . .6 The San (Bushmen) . .6 The Khoikhoi (Hottentots) . .8 BLACK SETTLEMENT . .9 THE NGUNI . .9 The Xhosa . .10 The Zulu . .11 The Ndebele . .12 The Swazi . .13 THE SOTHO . .13 The Western Sotho . .14 The Southern Sotho . .14 The Northern Sotho (Bapedi) . .14 THE VENDA . .15 THE MASHANGANA-TSONGA . .15 THE MFECANE/DIFAQANE (Total war) Dingiswayo . .16 Shaka . .16 Dingane . .18 Mzilikazi . .19 Soshangane . .20 Mmantatise . .21 Sikonyela . .21 Moshweshwe . .22 Consequences of the Mfecane/Difaqane . .23 Page 1 EUROPEAN INTERESTS The Portuguese . .24 The British . .24 The Dutch . .25 The French . .25 THE SLAVES . .22 THE TREKBOERS (MIGRATING FARMERS) . .27 EUROPEAN OCCUPATIONS OF THE CAPE British Occupation (1795 - 1803) . .29 Batavian rule 1803 - 1806 . .29 Second British Occupation: 1806 . .31 British Governors . .32 Slagtersnek Rebellion . .32 The British Settlers 1820 . .32 THE GREAT TREK Causes of the Great Trek . .34 Different Trek groups . .35 Trichardt and Van Rensburg . .35 Andries Hendrik Potgieter . .35 Gerrit Maritz . .36 Piet Retief . .36 Piet Uys . .36 Voortrekkers in Zululand and Natal . .37 Voortrekker settlement in the Transvaal . .38 Voortrekker settlement in the Orange Free State . .39 THE DISCOVERY OF DIAMONDS AND GOLD . .41 Page 2 EVOLUTION OF AFRICAN SOCIETIES Humankind had its earliest origins in Africa The introduction of iron changed the African and the story of life in South Africa has continent irrevocably and was a large step proven to be a micro-study of life on the forwards in the development of the people. -

The Geology of the Country Around Potchefstroom and Klerksdorp

r I! I I . i UNION OF SOUTH AFRICA DJ;;~!~RTMENT OF MINES GEOLOGICAL SURVEY THE GEOLOGY OF THE COUNTRY AROUND POTCHEFSTROOM AND KLERKSDORP , An Explanation of Sheet No. 61 (Potchefstroom). BY LOUIS T. NEL, D.Se., F.G.S., F. C. TRUTER, M.A., Ph.D, J. WILLEMSE, Ph.D., incorporating previous observations by E. T. MELLOR, D.Se., F,G.S. Published by Authority of the Honourable the Minister of Mines {COPYRiGHT1 PRINTED IN THE UNION OF SoUTH AFRICA BY THE GOVERNMENT PRINTER. PRETORIA 1939 G.P.-S.4423-1939-1,500. 9 ,ad ;est We are indebted to Western Reefs Exploration and Development Company, Limited, and to the Union Corporation, Limited, who have generously furnished geological information obtained in the red course of their drilling in the country about Klerksdorp. We are also :>7 1 indebted to Dr. p, F. W, Beetz whose presentation of the results of . of drilling carried out by the same company provides valuable additions 'aal to the knowledge of the geology of the district, and to iVIr. A, Frost the for his ready assistance in furnishing us with the results oUhe surveys the and drilling carried out by his company, Through the kind offices ical of Dr. A, L du Toit we were supplied with the production of diamonds 'ing in the area under description which is incorporated in chapter XL lim Other sources of information or assistance given are specifically ers acknowledged at appropriate places in this report. (LT,N.) the gist It-THE AREA AND ITS PHYSICAL FEATURES, ond The area described here is one of 2,128 square miles and extends )rs, from latitude 26° 30' to 27° south and from longtitude 26° 30' to the 27° 30' east. -

COVID-19 Laboratory Testing Sites

Care | Dignity | Participation | Truth | Compassion COVID-19 Laboratory testing sites Risk assessment, screening and laboratory testing for COVID-19 The information below should give invididuals a clear understanding of the process for risk assessment, screening and laboratory testing of patients, visitors, staff, doctors and other healthcare providers at Netcare facilities: • Risk assessment, screening and laboratory testing of ill individuals Persons who are ill are allowed access to the Netcare facility via the emergency department for risk assessment and screening. Thereafter the person will be clinically assessed by a doctor and laboratory testing for COVID-19 will subsequently be done if indicated. • Laboratory testing of persons sent by external doctors for COVID-19 laboratory testing at a Netcare Group facility Individuals who have been sent to a Netcare Group facility for COVID-19 laboratory testing by a doctor who is not practising at the Netcare Group facility will not be allowed access to the laboratories inside the Netcare facility, unless the person requires medical assistance. This brochure which contains a list of Ampath, Lancet and Pathcare laboratories will be made available to individuals not needing medical assistance, to guide them as to where they can have the testing done. In the case of the person needing medical assistance, they will be directed to the emergency department. No person with COVID-19 risk will be allowed into a Netcare facility for laboratory testing without having consulted a doctor first. • Risk assessment and screening of all persons wanting to enter a Netcare Group facility Visitors, staff, external service providers, doctors and other healthcare providers are being risk assessed at established points outside of Netcare Group hospitals, primary care centres and mental health facilities, prior to them entering the facility. -

Directory of Organisations and Resources for People with Disabilities in South Africa

DISABILITY ALL SORTS A DIRECTORY OF ORGANISATIONS AND RESOURCES FOR PEOPLE WITH DISABILITIES IN SOUTH AFRICA University of South Africa CONTENTS FOREWORD ADVOCACY — ALL DISABILITIES ADVOCACY — DISABILITY-SPECIFIC ACCOMMODATION (SUGGESTIONS FOR WORK AND EDUCATION) AIRLINES THAT ACCOMMODATE WHEELCHAIRS ARTS ASSISTANCE AND THERAPY DOGS ASSISTIVE DEVICES FOR HIRE ASSISTIVE DEVICES FOR PURCHASE ASSISTIVE DEVICES — MAIL ORDER ASSISTIVE DEVICES — REPAIRS ASSISTIVE DEVICES — RESOURCE AND INFORMATION CENTRE BACK SUPPORT BOOKS, DISABILITY GUIDES AND INFORMATION RESOURCES BRAILLE AND AUDIO PRODUCTION BREATHING SUPPORT BUILDING OF RAMPS BURSARIES CAREGIVERS AND NURSES CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — EASTERN CAPE CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — FREE STATE CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — GAUTENG CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — KWAZULU-NATAL CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — LIMPOPO CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — MPUMALANGA CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — NORTHERN CAPE CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — NORTH WEST CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — WESTERN CAPE CHARITY/GIFT SHOPS COMMUNITY SERVICE ORGANISATIONS COMPENSATION FOR WORKPLACE INJURIES COMPLEMENTARY THERAPIES CONVERSION OF VEHICLES COUNSELLING CRÈCHES DAY CARE CENTRES — EASTERN CAPE DAY CARE CENTRES — FREE STATE 1 DAY CARE CENTRES — GAUTENG DAY CARE CENTRES — KWAZULU-NATAL DAY CARE CENTRES — LIMPOPO DAY CARE CENTRES — MPUMALANGA DAY CARE CENTRES — WESTERN CAPE DISABILITY EQUITY CONSULTANTS DISABILITY MAGAZINES AND NEWSLETTERS DISABILITY MANAGEMENT DISABILITY SENSITISATION PROJECTS DISABILITY STUDIES DRIVING SCHOOLS E-LEARNING END-OF-LIFE DETERMINATION ENTREPRENEURIAL -

![NORTH WEST I NOORDWES ~ ~ ~ PROVINCIAL GAZETTE ~ I PROVINCIAL GAZETTE I ~ ~ ~@].@]~ ~ ~ ~ JUNE ~ ~ Vol](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2135/north-west-i-noordwes-provincial-gazette-i-provincial-gazette-i-june-vol-942135.webp)

NORTH WEST I NOORDWES ~ ~ ~ PROVINCIAL GAZETTE ~ I PROVINCIAL GAZETTE I ~ ~ ~@].@]~ ~ ~ ~ JUNE ~ ~ Vol

l!: @] ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ NORTH WEST i NOORDWES ~ ~ ~ PROVINCIAL GAZETTE ~ I PROVINCIAL GAZETTE i ~ ~ ~@].@]~ ~ ~ ~ JUNE ~ ~ Vol. 252 30 JUNIE 2009 No. 6653 ~ I I @] @] 2 No. 6653 PROVINCIAL GAZETTE, 30 JUNE 2009 CONTENTS INHOUD Page Gazette Bladsy Koerant No. No. No. No. No. No. GENERAL NOTICES ALGEMENE KENNISGEWINGS 197 Town-planning and Townships 197 Ordonnansie op Dorpsbeplanning en Ordinance (15/1986): Amendment Dorpe (15/1986): Wysigingskema 25...... 8 6653 Scheme 25 . 8 6653 198 do.: Rustenburg-wysigingskema 547...... 9 6653 198 do.: Rustenburg Amendment Scheme 199 do.: Ditsobotla-wysigingskema 43 .......... 9 6653 547 .. 8 6653 200 Wet op Opheffing van Beperkings 199 do.: Ditsobotla Amendment Scheme 43 . 9 6653 (84/1967): Opheffing van voorwaardes: 200 Removal of Restrictions Act (84/1967): Erf 2449, Flamwood 10 6653 Removal of conditions: Erf 2449, Flamwood . 10 6653 PLAASLIKE BESTUURSKENNISGEWINGS 208 Town-planning and Townships LOCAL AUTHORITY NOTICES Ordinance (15/1986): Local Municipality 208 Town-planning and Townships of Madibeng: Brits Amendment Scheme Ordinance (15/1986): Local Municipality 1/465....................................................... 10 6653 of Madibeng: Brits Amendment Scheme 209 Ordonnansie op Dorpsbeplanning en 1/465 . 10 6653 Dorpe (15/1986): Madibeng Muni 209 do.: do.: Rezoning: Erf 1874, Brits X9 .. 11 6653 sipaliteit: Hersonering: Erf 1874, 210 Rustenburg Amendment Scheme 478: Brits X9.................................................... 11 6653 Cancellation of notice .. 11 6653 210 Rustenburg-wysigingskema 478: Kansel- 211 Rustenburg Amendment Scheme 421: lasie van kennisgewing............................. 12 6653 Cancellation of notice . 12 6653 211 Rustenburg-wysigingskema 421: Kansel- 212 Local Government Ordinance (17/1939): lasie van kennisgewing 12 6653 Maquassi Hills Local Municipality: 212 Ordonnansie op Plaaslike Bestuur Closing: Portion of street adjacent to Erf (17/1939): Maquassi Hills Plaaslike 599 and Erf 600, Wolmaransstad Munisipaliteit: Sluiting: Gedeelte van Extension 5 . -

A Study Into the Meanings of Sports As a Medium of HIV Awareness in a South African Township

Active HIV Awareness A study into the meanings of sports as a medium of HIV awareness in a South African township Utrecht University Utrecht School of Governance Organization, Culture & Management Author: Maikel Waardenburg Utrecht, February 2006 Active HIV Awareness A study into the meanings of sports as a medium of HIV awareness in a South African township Utrecht University Utrecht School of Governance Organization, Culture & Management Supervisor: drs. Marinette Oomen Author: Maikel Waardenburg Himalaya 164 3524 XJ Utrecht, the Netherlands [email protected] Student number: 0144274 Utrecht, February 2006 The picture on the cover of this document is property of Martijn Bergmans Extensive paper written for the final year of the study ‘Public Administration & Organizational Science’ at Utrecht University Active HIV Awareness Contents Summary iv List of Tables and Figures vi List of Abbreviations vii Acknowledgements viii Introduction 1 Chapter 1 Research Design 3 1.1 Central Research Question 3 1.2 Research Paradigm 4 1.3 Research Object 5 1.4 Research Methods 5 1.4.1 Observations 5 1.4.2 Interviews 6 1.4.3 Participation 7 1.5 Public and Scientific Relevance 8 Chapter 2 The Big Picture 10 2.1 Early South Africa 10 2.2 Political Struggle in South Africa 11 2.3 Present-day South Africa 13 2.3.1 Present-day Government & Politics 14 2.3.2 Economy of South Africa 16 2.3.3 Socio-cultural features of South Africa 17 2.4 The HIV/AIDS Pandemic in South Africa 17 2.4.1 HIV Determinants in South Africa 19 2.4.2 Government’s Response -

Wetland Plant Communities in the Potchefstroom Municipal Area, North-West, South Africa

Bothalia 28,2: 213-229 (1998) Wetland plant communities in the Potchefstroom Municipal Area, North-West, South Africa S.S. CILLIERS*, L.L. SCHOEMAN* and G.J. BREDENKAMP** Keywords: Braun-Blanquet, DECORANA. disturbed areas, MEGATAB, TURBOVEG. TWINSPAN, urban open spaces ABSTRACT Wetlands in natural areas in South Africa have been described before, but no literature exists concerning the phyto sociology of urban wetlands. The objective of this study was to conduct a complete vegetation analysis of the wetlands in the Potchefstroom Municipal Area. Using a numerical classification technique (TWINSPAN) as a first approximation, the classification was refined by using Braun-Blanquet procedures. The result is a phytosociological table from which a number of unique plant communities are recognised. These urban wetlands are characterised by a high species diversity, which is unusual for wetlands. Reasons for the high species diversity could be the different types of disturbances occurring in this area. Results of this study can be used to construct more sensible management practises for these wetlands. CONTENTS Many natural wetlands have been destroyed in the course of agricultural, industrial and urban development Introduction..............................................................213 (Archibald & Batchelor 1992), and are regarded as one Study area................................................................ 215 of South Africa’s most endangered ecosystem types Materials and methods..............................................215 (Walmsley -

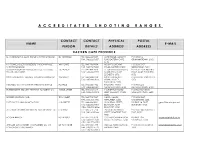

Accreditated Shooting Ranges

A C C R E D I T A T E D S H O O T I N G R A N G E S CONTACT CONTACT PHYSICAL POSTAL NAME E-MAIL PERSON DETAILS ADDRESS ADDRESS EASTERN CAPE PROVINCE D J SURRIDGE T/A ALOE RIDGE SHOOTING RANGE DJ SURRIDGE TEL: 046 622 9687 ALOE RIDGE MANLEY'S P O BOX 12, FAX: 046 622 9687 FLAT, EASTERN CAPE, GRAHAMSTOWN, 6140 6140 K V PEINKE (SOLE PROPRIETOR) T/A BONNYVALE WK PEINKE TEL: 043 736 9334 MOUNT COKE KWT P O BOX 5157, SHOOTING RANGE FAX: 043 736 9688 ROAD, EASTERN CAPE GREENFIELDS, 5201 TOMMY BOSCH AND ASSOCIATES CC T/A LOCK, T C BOSCH TEL: 041 484 7818 51 GRAHAMSTAD ROAD, P O BOX 2564, NOORD STOCK AND BARREL FAX: 041 484 7719 NORTH END, PORT EINDE, PORT ELIZABETH, ELIZABETH, 6056 6056 SWALLOW KRANTZ FIREARM TRAINING CENTRE CC WH SCOTT TEL: 045 848 0104 SWALLOW KRANTZ P O BOX 80, TARKASTAD, FAX: 045 848 0103 SPRING VALLEY, 5370 TARKASTAD, 5370 MECHLEC CC T/A OUTSPAN SHOOTING RANGE PL BAILIE TEL: 046 636 1442 BALCRAIG FARM, P O BOX 223, FAX: 046 636 1442 GRAHAMSTOWN, 6140 GRAHAMSTOWN, 6140 BUTTERWORTH SECURITY TRAINING ACADEMY CC WB DE JAGER TEL: 043 642 1614 146 BUFFALO ROAD, P O BOX 867, KING FAX: 043 642 3313 KING WILLIAM'S TOWN, WILLIAM'S TOWN, 5600 5600 BORDER HUNTING CLUB TE SCHMIDT TEL: 043 703 7847 NAVEL VALLEY, P O BOX 3047, FAX: 043 703 7905 NEWLANDS, 5206 CAMBRIDGE, 5206 EAST CAPE PLAINS GAME SAFARIS J G GREEFF TEL: 046 684 0801 20 DURBAN STREET, PO BOX 16, FORT [email protected] FAX: 046 684 0801 BEAUFORT, FORT BEAUFORT, 5720 CELL: 082 925 4526 BEAUFORT, 5720 ALL ARMS FIREARM ASSESSMENT AND TRAINING CC F MARAIS TEL: 082 571 5714 -

South African Jewish Board of Deputies Report of The

The South African Jewish Board of Deputies JL 1r REPORT of the Executive Council for the period July 1st, 1933, to April 30th, 1935. To be submitted to the Eleventh Congress at Johannesburg, May 19th and 20th, 1935. <י .H.W.V. 8. Co י É> S . 0 5 Americanist Commiitae LIBRARY 1 South African Jewish Board of Deputies. EXECUTIVE COUNCIL. President : Hirsch Hillman, Johannesburg. Vice-President» : S. Raphaely, Johannesburg. Morris Alexander, K.C., M.P., Cape Town. H. Moss-Morris, Durban. J. Philips, Bloemfontein. Hon. Treasurer: Dr. Max Greenberg. Members of Executive Council: B. Alexander. J. Alexander. J. H. Barnett. Harry Carter, M.P.C. Prof. Dr. S. Herbert Frankel. G. A. Friendly. Dr. H. Gluckman. J. Jackson. H. Katzenellenbogen. The Chief Rabbi, Prof. Dr. j. L. Landau, M.A., Ph.D. ^ C. Lyons. ^ H. H. Morris Esq., K.C. ^י. .B. L. Pencharz A. Schauder. ^ Dr. E. B. Woolff, M.P.C. V 2 CONSTITUENT BODIES. The Board's Constituent Bodies are as. follows :— JOHANNESBURG (Transvaal). 1. Anykster Sick Benefit and Benevolent Society. 2. Agoodas Achim Society. 3. Beth Hamedrash Hagodel. 4. Berea Hebrew Congregation. 5. Bertrams Hebrew Congregation. 6. Braamfontein Hebrew Congregation. 7. Chassidim Congregation. 8. Club of Polish Jews. 9. Doornfontein Hebrew:: Congregation.^;7 10. Eastern Hebrew Benevolent Society. 11. Fordsburg Hebrew Congregation. 12. Grodno Sifck Benefit and Benevolent Society. 13. Habonim. 14. Hatechiya Organisation. 15. H.O.D. Dr. Herzl Lodge. 16. H.O.D. Sir Moses Montefiore Lodge. 17. Jeppes Hebrew Congregation, 18. Johannesburg Jewish Guild. 19. Johannesburg Jewish Helping Hand and Burial Society. -

19Th Century Tragedy, Victory, and Divine Providence As the Foundations of an Afrikaner National Identity

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University History Theses Department of History Spring 5-7-2011 19th Century Tragedy, Victory, and Divine Providence as the Foundations of an Afrikaner National Identity Kevin W. Hudson Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/history_theses Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Hudson, Kevin W., "19th Century Tragedy, Victory, and Divine Providence as the Foundations of an Afrikaner National Identity." Thesis, Georgia State University, 2011. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/history_theses/45 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of History at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in History Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 19TH CENTURY TRAGEDY, VICTORY, AND DIVINE PROVIDENCE AS THE FOUNDATIONS OF AN AFRIKANER NATIONAL IDENTITY by KEVIN W. HUDSON Under the DireCtion of Dr. Mohammed Hassen Ali and Dr. Jared Poley ABSTRACT Apart from a sense of racial superiority, which was certainly not unique to white Cape colonists, what is clear is that at the turn of the nineteenth century, Afrikaners were a disparate group. Economically, geographically, educationally, and religiously they were by no means united. Hierarchies existed throughout all cross sections of society. There was little political consciousness and no sense of a nation. Yet by the end of the nineteenth century they had developed a distinct sense of nationalism, indeed of a volk [people; ethnicity] ordained by God. The objective of this thesis is to identify and analyze three key historical events, the emotional sentiments evoked by these nationalistic milestones, and the evolution of a unified Afrikaner identity that would ultimately be used to justify the abhorrent system of apartheid. -

Groundwater and Surface Water) Quality and Management in the North-West Province, South Africa

A scoping study on the environmental water (groundwater and surface water) quality and management in the North-West Province, South Africa Report to the WATER RESEARCH COMMISSION by CC Bezuidenhout and the North-West University Team WRC Report No. KV 278/11 ISBN No 978-1-4312-0174-7 October 2011 The publication of this report emanates from a WRC project titled A scoping study on the environmental water (groundwater and surface water) quality and management in the north- West Province, south Africa (WRC Project No. K8/853) DISCLAIMER This report has been reviewed by the Water Research Commission (WRC) and approved for publication. Approval does not signify that the contents necessarily reflect the views and policies of the WRC nor does mention of trade names or commercial products constitute endorsement or recommendation for use. ii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY BACKGROUND & RATIONALE Water in the North West Province is obtained from ground and surface water sources. The latter are mostly non-perennial and include rivers and inland lakes and pans. Groundwater is thus a major source and is used for domestic, agriculture and mining purposes mostly without prior treatment. Furthermore, there are several pollution impacts (nitrates, organics, microbiological) that are recognised but are not always addressed. Elevated levels of inorganic substances could be due to natural geology of areas but may also be due to pollution. On the other hand, elevated organic substances are generally due to pollution from sanitation practices, mining activities and agriculture. Water quality data are, however, fragmented. A large section of the population of the North West Province is found in rural settings and most of them are affected by poverty. -

British Scorched Earth and Concentration Camp Policies

72 THE BRITISH SCORCHED EARTH AND CONCENTRATION CAMP POLICIES IN THE 1 POTCHEFSTROOM REGION, 1899–1902 Prof GN van den Bergh Research Associate, North-West University Abstract The continued military resistance of the Republics after the occupation of Bloemfontein and Pretoria and exaggerated by the advent of guerrilla tactics frustrated the British High Command. In the case of the Potchefstroom region, British aggravation came to focus on the successful resurgence of the Potchefstroom Commando, under Gen. Petrus Liebenberg, swelled by surrendered burghers from the Gatsrand again taking up arms. A succession of proclamations of increasing severity were directed at civilians for lending support to commandos had no effect on either the growth or success of Liebenberg’s commando. His basis for operations was the Gatsrand from where he disrupted British supply communications. He was involved in British evacuations of the town in July and August 1900 and in assisting De Wet in escaping British pursuit in August 1900. British policy came to revolve around denying Liebenberg use of the abundant food supplies in the Gatsrand by applying a scorched earth policy there and in the adjacent Mooi River basin. This occurred in conjuncture with the brief second and permanent third occupation of Potchefstroom. The subsequent establishment of garrisons there gave rise to the systematic destruction of the Gatsrand agricultural infrastructure. To deny further use of the region by commandos it was depopulated. In consequence, the first and largest concentration camp in the Transvaal was established in Potchefstroom. The policies succeeded in dispelling Liebenberg from the region. Introduction Two of the most controversial aspects of the Anglo Boer War are the closely related British scorched earth and concentration camp policies.