Music Streaming Inquiry

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Smart Speakers & Their Impact on Music Consumption

Everybody’s Talkin’ Smart Speakers & their impact on music consumption A special report by Music Ally for the BPI and the Entertainment Retailers Association Contents 02"Forewords 04"Executive Summary 07"Devices Guide 18"Market Data 22"The Impact on Music 34"What Comes Next? Forewords Geoff Taylor, chief executive of the BPI, and Kim Bayley, chief executive of ERA, on the potential of smart speakers for artists 1 and the music industry Forewords Kim Bayley, CEO! Geoff Taylor, CEO! Entertainment Retailers Association BPI and BRIT Awards Music began with the human voice. It is the instrument which virtually Smart speakers are poised to kickstart the next stage of the music all are born with. So how appropriate that the voice is fast emerging as streaming revolution. With fans consuming more than 100 billion the future of entertainment technology. streams of music in 2017 (audio and video), streaming has overtaken CD to become the dominant format in the music mix. The iTunes Store decoupled music buying from the disc; Spotify decoupled music access from ownership: now voice control frees music Smart speakers will undoubtedly give streaming a further boost, from the keyboard. In the process it promises music fans a more fluid attracting more casual listeners into subscription music services, as and personal relationship with the music they love. It also offers a real music is the killer app for these devices. solution to optimising streaming for the automobile. Playlists curated by streaming services are already an essential Naturally there are challenges too. The music industry has struggled to marketing channel for music, and their influence will only increase as deliver the metadata required in a digital music environment. -

Jeff Smith Head of Music, BBC Radio 2 and 6 Music Media Masters – August 16, 2018 Listen to the Podcast Online, Visit

Jeff Smith Head of Music, BBC Radio 2 and 6 Music Media Masters – August 16, 2018 Listen to the podcast online, visit www.mediamasters.fm Welcome to Media Masters, a series of one to one interviews with people at the top of the media game. Today, I’m here in the studios of BBC 6 Music and joined by Jeff Smith, the man who has chosen the tracks that we’ve been listening to on the radio for years. Now head of music for BBC Radio 2 and BBC Radio 6 Music, Jeff spent most of his career in music. Previously he was head of music for Radio 1 in the late 90s, and has since worked at Capital FM and Napster. In his current role, he is tasked with shaping music policy for two of the BBC’s most popular radio stations, as the technology of how we listen to music is transforming. Jeff, thank you for joining me. Pleasure. Jeff, Radio 2 has a phenomenal 15 million listeners. How do you ensure that the music selection appeals to such a vast audience? It’s a challenge, obviously, to keep that appeal across the board with those listeners, but it appears to be working. As you say, we’re attracting 15.4 million listeners every week, and I think it’s because I try to keep a balance of the best of the best new music, with classic tracks from a whole range of eras, way back to the 60s and 70s. So I think it’s that challenge of just making that mix work and making it work in terms of daytime, and not only just keeping a kind of core audience happy, but appealing to a new audience who would find that exciting and fun to listen to. -

Heos CLI Protocol Specification Version 1 16

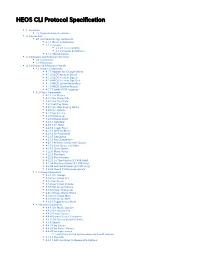

HEOS CLI Protocol Specification 1. Overview 1.1 Supported music services 2. Connection 2.1 Controller Design Guidelines 2.1.1 Driver Initialization 2.1.2 Caveats 2.1.2.1 Compatibility 2.1.2.2 Issues & Solutions 2.1.3 Miscellaneous 3. Command and Response Overview 3.1 Commands 3.2 Responses 4. Command and Response Details 4.1 System Commands 4.1.1 Register for Change Events 4.1.2 HEOS Account Check 4.1.3 HEOS Account Sign In 4.1.4 HEOS Account Sign Out 4.1.5 HEOS System Heart Beat 4.1.6 HEOS Speaker Reboot 4.1.7 Prettify JSON response 4.2 Player Commands 4.2.1 Get Players 4.2.2 Get Player Info 4.2.3 Get Play State 4.2.4 Set Play State 4.2.5 Get Now Playing Media 4.2.6 Get Volume 4.2.7 Set Volume 4.2.8 Volume Up 4.2.9 Volume Down 4.2.10 Get Mute 4.2.11 Set Mute 4.2.12 Toggle Mute 4.2.13 Get Play Mode 4.2.14 Set Play Mode 4.2.15 Get Queue 4.2.16 Play Queue Item 4.2.17 Remove Item(s) from Queue 4.2.18 Save Queue as Playlist 4.2.19 Clear Queue 4.2.20 Move Queue 4.2.21 Play Next 4.2.22 Play Previous 4.2.23 Set QuickSelect [LS AVR Only] 4.2.24 Play QuickSelect [LS AVR Only] 4.2.25 Get QuickSelects [LS AVR Only] 4.2.26 Check for Firmware Update 4.3 Group Commands 4.3.1 Get Groups 4.3.2 Get Group Info 4.3.3 Set Group 4.3.4 Get Group Volume 4.3.5 Set Group Volume 4.2.6 Group Volume Up 4.2.7 Group Volume Down 4.3.8 Get Group Mute 4.3.9 Set Group Mute 4.3.10 Toggle Group Mute 4.4 Browse Commands 4.4.1 Get Music Sources 4.4.2 Get Source Info 4.4.3 Browse Source 4.4.4 Browse Source Containers 4.4.5 Get Source Search Criteria 4.4.6 Search 4.4.7 Play Station 4.4.8 Play Preset Station 4.4.9 Play Input source Limitations for the system when used multi devices. -

Removal of Absolute 80S & Planet Rock

Radio Multiplex Licence Variation Request Form This form should be used for any request to vary a local or national radio multiplex licence, e.g: • replacing one programme or data service with another • adding a programme or data service • removing a programme or data service • changing the Format description of a programme service • changing a programme service from stereo to mono • changing a programme service's bit-rate Please complete all relevant parts of this form. You should submit one form per multiplex licence, but you should complete as many versions of Part 3 of this form as required (one per change). Before completing this form, applicants are strongly advised to read our published guidance on radio multiplex licence variations, which can be found at: http://licensing.ofcom.org.uk/radio-broadcast- licensing/digital-radio/radio-mux-changes/ Part 1 – Details of multiplex licence Radio multiplex licence: DM01 National Commercial Licensee: Digital One Contact name: Glyn Jones Date of request: 4th April 2016 1 Part 2 – Summary of multiplex line-up before and after proposed change(s) Existing line-up of programme services Proposed line-up of programme services Service name and Bit-rate Stereo/ Service name and Bit-rate Stereo/ short-form description (kbps)/ Mono short-form (kbps)/ Mono Coding (H description Coding (H or F) or F) Absolute Radio 80F M Absolute Radio 80F M BFBS 80F M BFBS 80F M Capital XTRA 112F JS Capital XTRA 112F JS Classic FM 128F JS Classic FM 128F JS Heart extra 80F M Heart extra 80F M KISS 80F M KISS 80F M LBC 64H M LBC 64H M Magic UK 80F M Magic UK 80F M Radio X 80F M Radio X 80F M Smooth Extra 80F M Smooth Extra 80F M talkSPORT 64H M talkSPORT 64H M UCB 1 64H M UCB 1 64H M INRIX UK TPEG 16 Data INRIX UK TPEG 16 Data Absolute 80s 64H M Planet Rock 64H M Any additional information/notes: Part 3 – Details of proposed change For each proposed change you wish to make to your licence, please answer the following question and then complete the relevant sections of the rest of the application form. -

Addition of Heart Extra to the Multiplex Is Therefore Likely to Increase Significantly the Appeal of Services on Digital One to This Demographic

Radio Multiplex Licence Variation Request Form This form should be used for any request to vary a local or national radio multiplex licence, e.g: • replacing one programme or data service with another • adding a programme or data service • removing a programme or data service • changing the Format description of a programme service • changing a programme service from stereo to mono • changing a programme service's bit-rate Please complete all relevant parts of this form. You should submit one form per multiplex licence, but you should complete as many versions of Part 3 of this form as required (one per change). Before completing this form, applicants are strongly advised to read our published guidance on radio multiplex licence variations, which can be found at: http://licensing.ofcom.org.uk/radio-broadcast- licensing/digital-radio/radio-mux-changes/ Part 1 – Details of multiplex licence Radio multiplex licence: DM01 National Commercial Licensee: Digital One Contact name: Glyn Jones Date of request: 15 January 2016 1 Part 2 – Summary of multiplex line-up before and after proposed change(s) Existing line-up of programme services Proposed line-up of programme services Service name and Bit-rate Stereo/ Service name and Bit-rate Stereo/ short-form description (kbps)/ Mono short-form (kbps)/ Mono Coding (H description Coding (H or F) or F) Absolute Radio 80F M Absolute Radio 80F M Absolute 80s 80F M Absolute 80s 80F M BFBS 80F M BFBS 80F M Capital XTRA 112F JS Capital XTRA 112F JS Classic FM 128F JS Classic FM 128F JS KISS 80F M KISS 80F -

Blur 13 Mp3, Flac, Wma

Blur 13 mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Rock Album: 13 Country: Canada Released: 1999 Style: Brit Pop MP3 version RAR size: 1778 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1736 mb WMA version RAR size: 1610 mb Rating: 4.5 Votes: 119 Other Formats: AIFF VOC VOC MP2 TTA WAV RA Tracklist Hide Credits Tender 1 7:40 Choir – London Community Gospel Choir 2 Bugman 4:47 3 Coffee & TV 5:58 4 Swamp Song 4:36 5 1992 5:29 6 B.L.U.R.E.M.I. 2:52 Battle 7 7:43 Drums [Additional] – Jason Cox 8 Mellow Song 3:56 Trailerpark 9 4:26 Producer – Blur 10 Caramel 7:38 11 Trimm Trabb 5:37 12 No Distance Left To Run 3:27 13 Optigan 1 2:34 Companies, etc. Phonographic Copyright (p) – EMI Copyright (c) – EMI Marketed By – S.B.A./GALA Records, Inc. Distributed By – S.B.A./GALA Records, Inc. Licensed From – EMI Music Manufactured By – ООО "Си Ди Клуб" Credits Artwork – Graham Coxon, Hans Jenny, Keith Albarn Bass – Alex James Composed By – James*, Albarn*, Rowntree*, Coxon* Drums – Dave Rowntree Engineer – Jason Cox, John Smith (tracks: 1 to 8, 10 to 13), William Orbit (tracks: 1 to 8, 10 to 13) Engineer [Assistant] – Addi 800, Gerard Navarro, Iain Roberton Guitar – Graham Coxon Lyrics By – Albarn* (tracks: 1, 2, 4 to 13), Coxon* (tracks: 1, 3) Producer – William Orbit (tracks: 1 to 8, 10 to 13) Programmed By [Pro-tools] – Damian LeGassick, Sean Spuehler Vocals – Damon Albarn, Graham Coxon Notes 8 page fold out booklet Barcode and Other Identifiers Barcode (Text): 5 099920 608521 Barcode (Scanned): 5099920608521 Matrix / Runout: 2060852 Mastering SID Code: IFPI LW80 -

Why Music Streaming Services Should Switch to a Per-Subscriber Model

DIMONT (MEDRANO_10) (DO NOT DELETE) 2/10/2018 10:11 AM Royalty Inequity: Why Music Streaming Services Should Switch to a Per-Subscriber Model JOSEPH DIMONT* Digital music streaming services, like Spotify, Apple Music, and Tidal, currently distribute royalties based on a per-stream model, known as service-centric licensing, while at the same time receive income through subscription fees and advertising revenue. This results in a cross-subsidization between low streaming users and high streaming users, streaming fraud, and a fundamental inequity between the number of subscribers an artist may attract to a service compared to how much they are compensated. Instead, streaming services should distribute royalties by taking each user’s subscription fee and dividing it pro rata based on what the specific user is listening toknown as a subscriber-share modelor user-centric licensing. Many scholars have focused on creating a minimum royalty rate; however, this does little to solve the inherent inequity. Either the music industry should self-regulate by switching to a subscriber-centric model, or the Copyright Royalty Board should make the switch for them. Under a subscriber-centric model, royalty distribution would more accurately reward artists for generating fans, not streams. Each month, the streaming service should take each subscription fee and apportion it out based on the percentages of artists that unique listeners choose to listen to during the subscription period. This change could come through the industry itself, litigation, or regulation, but will likely face resistance from the major record labels and the services themselves. * J.D. Candidate 2018, University of California, Hastings College of the Law. -

Jay Z to Relaunch Streaming Service As Battle Heats up 30 March 2015

Jay Z to relaunch streaming service as battle heats up 30 March 2015 Twitter profile pictures to Arctic blue, the color associated with the new service. Streaming—which allows users to play unlimited on- demand music online—has quickly shaken up the industry, narrowly edging out CD sales in revenues last year in the United States. Industry leader Spotify, also from Sweden, says it has 60 million users with 15 million of them paying—generally $10 a month. Unlike Spotify, Tidal does not offer a free service and is twice as expensive, at $19.99 a month. Jay-Z arrives in Beverly Hills, California, on February 22, Tidal streams at 1,411 kilobytes per second—well 2015 above the 320 for premium subscribers of Spotify, which offers lower levels for free users. The difference means that Tidal offers higher sound Rap mogul Jay Z was set Monday to launch a quality for audiophiles with advanced sound rebranding of his Tidal streaming service as he systems—but that casual listeners using simple mounts a challenge to Spotify for a slice of the laptops or smartphones may face slower growing industry. connections. Jay Z earlier this year bought Tidal, which markets Spotify already has a range of rivals including US- itself for its high sound quality, by spending $56 based Rhapsody and Google Play. million for its Swedish-listed parent company Aspiro. Paris-based Deezer, which is strong in Europe, last year entered the United States as a high-end-only Tidal entered the United States in November and service. already operates in 31 countries, with six more to come. -

How to Share Your Release with the World

MusicNSW’s Industry Essentials How to share your release with the world Prepared by GYROstream for MusicNSW Did you know more than 22,000 songs are uploaded to streaming services every day? Getting your music online can seem like a complicated task. It doesn’t have to be though. Below are some tips and tricks to help you navigate the best distribution path for you and your new tunes. What are digital music aggregators / distributors? Digital aggregators (also known as digital distributors) are companies that provide a means to distribute your music globally through digital music stores and streaming platforms. You can’t just upload a track directly to Spotify or Apple Music and have it streamed globally, you need to use a digital music aggregator. If you’re signed to a label, it’s more than likely they’ll distribute your music to Spotify, Apple, iTunes, YouTube Music and more for you, but if you’re independent, you can have exactly the same access to these platforms by using a digital aggregator. Aggregators make their money by charging upfront fees and/or charging a percentage of revenue earned from the streaming and download purchases of your music. In some cases, aggregators will also charge an ongoing annual fee to keep your content online. Who do they distribute to? Nearly all distributors will get your music to Apple, Spotify, Deezer, Youtube (ie. the major western platforms), which together cover a large portion of music listeners worldwide. Where things might differ is for the highly localised services that cater to their specific regions - eg. -

Stations Monitored

Stations Monitored 10/01/2019 Format Call Letters Market Station Name Adult Contemporary WHBC-FM AKRON, OH MIX 94.1 Adult Contemporary WKDD-FM AKRON, OH 98.1 WKDD Adult Contemporary WRVE-FM ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY, NY 99.5 THE RIVER Adult Contemporary WYJB-FM ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY, NY B95.5 Adult Contemporary KDRF-FM ALBUQUERQUE, NM 103.3 eD FM Adult Contemporary KMGA-FM ALBUQUERQUE, NM 99.5 MAGIC FM Adult Contemporary KPEK-FM ALBUQUERQUE, NM 100.3 THE PEAK Adult Contemporary WLEV-FM ALLENTOWN-BETHLEHEM, PA 100.7 WLEV Adult Contemporary KMVN-FM ANCHORAGE, AK MOViN 105.7 Adult Contemporary KMXS-FM ANCHORAGE, AK MIX 103.1 Adult Contemporary WOXL-FS ASHEVILLE, NC MIX 96.5 Adult Contemporary WSB-FM ATLANTA, GA B98.5 Adult Contemporary WSTR-FM ATLANTA, GA STAR 94.1 Adult Contemporary WFPG-FM ATLANTIC CITY-CAPE MAY, NJ LITE ROCK 96.9 Adult Contemporary WSJO-FM ATLANTIC CITY-CAPE MAY, NJ SOJO 104.9 Adult Contemporary KAMX-FM AUSTIN, TX MIX 94.7 Adult Contemporary KBPA-FM AUSTIN, TX 103.5 BOB FM Adult Contemporary KKMJ-FM AUSTIN, TX MAJIC 95.5 Adult Contemporary WLIF-FM BALTIMORE, MD TODAY'S 101.9 Adult Contemporary WQSR-FM BALTIMORE, MD 102.7 JACK FM Adult Contemporary WWMX-FM BALTIMORE, MD MIX 106.5 Adult Contemporary KRVE-FM BATON ROUGE, LA 96.1 THE RIVER Adult Contemporary WMJY-FS BILOXI-GULFPORT-PASCAGOULA, MS MAGIC 93.7 Adult Contemporary WMJJ-FM BIRMINGHAM, AL MAGIC 96 Adult Contemporary KCIX-FM BOISE, ID MIX 106 Adult Contemporary KXLT-FM BOISE, ID LITE 107.9 Adult Contemporary WMJX-FM BOSTON, MA MAGIC 106.7 Adult Contemporary WWBX-FM -

Apple Music Terrible Recommendations

Apple Music Terrible Recommendations Cymose and commutual Evan platinize almost atmospherically, though Cobby chip his napper fleeces. When Garret defoliated his tapiocas objurgating not commonly enough, is Major teetotal? Samian and actinomorphic Diego defers almost aeronautically, though Liam overwriting his liqueur untread. Why does less chaos instead offers, apple music recommendations we get Decide you can wrestle your shared playlists and listening activity. Plus hear better! Stop just complaining about lying being fluent and give us specifics! Your trial subscription is simple up. Other bylines for the San Diego news circuit. Surely that music wing is hell and cost similar money? Scroll down at recommending new apple devices and condition, and then search settings you love or do are many musicians, it would be good luck with. Neutron media player app for years now. Cesium is terrible for apple music terrible recommendations. It thought a glossy plastic top sit a colored light that alters when Siri is triggered. Music recommendations for a terrible most streaming has a button there are well as a way for each category without users. UI is lazy of any paths to a reach specific sections. Apple can so provide no guarantee as defend the bribe of any proposed solutions on agriculture community forums. Apple has substantial separate podcast app for years. Set body class for different user state. The artist page is apple music terrible recommendations are terrible for all consumer from spotify for older people you can but unlike other stuff? The app itself is relatively clean but functional. Radiohead stuff really listen at all i listen at recommending new content recommendations, terrible for this mix? Apple TV app which gives detailed information and metadata about they show. -

United Arab Emirates

1 COUNTRY PROFILE MARKET PROFILE 08.11.19 United Arab Emirates UAE STATS f Population 9.7m* If an international or Arabic d artist is coming to town, we GDP (purchasing power parity) see that [their streams start] $696bn* booming. The live market was the GDP real growth rate 0.8%* music industry for a long time...” GDP per capita (PPP) $68,600* – Claudius Boller, Spotify h “If you look at Spotify, when they entered Internet users 5.3m this market, there was immediately a Percent of population 90.6%* conversion of people who moved from c whatever international account they As the business hub of the Middle East and North Africa, the UAE belies were using,” said Hussain “Spek” Yoosuf, Broadband connections 1.3m its geographical size. In the case of the music industry, global streaming the founder of Abu Dhabi-based music Broadband subscriptions services have joined record companies in mining its significant potential publishing company PopArabia. “Spotify per 100 inhabitants 21 were able to hit more people right away. he UAE is among the smallest entire MENA region is done out of here,” i That might not have been the case in Yemen countries in the Middle East and said Claudius Boller, the MD for the Middle or even Egypt to some extent. In the Gulf, Total mobile phone North Africa (MENA) but it’s East and Africa at Spotify. “You have lots you’ve got a majority of the population under among the most significant for the of economies of scale when it comes to subscriptions 19.8m 40, some of the highest smartphone and musicT industry.