Nonrefundable Retainers: Impermissible Under Fiduciary, Statutory and Contract Law

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LARC @ Cardozo Law 1998-1999

Yeshiva University, Cardozo School of Law LARC @ Cardozo Law Student Handbooks Life @ Cardozo 1998 1998-1999 Benjamin N. Cardozo School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://larc.cardozo.yu.edu/student-handbooks Part of the Law Commons CARDOZO BENJAMIN N . CARDOZO SCHOOL OF LAW• YESHIVA UNIVERSITY Student Handbook 1998-99 This Handbook, effective September I, 1998, supersedes all previously published rules and regulations, announcements, statements, and publications with which it is inconsistent. The rules and regulations set forth in this Handbook are binding upon all students who are presently matriculated at Benjamin N. Cardozo School of Law (CSL), who are on leave of absence from CSL, or who are CSL students visiting at other law schools. Students are deemed to have read and understood both this Handbook and the CSL Bulletin (catalogue). Any questions concerning the contents of the Student Handbook or the CSL Bulletin should be addressed to the Office of the Dean. CSL reserves the right to change its rules and regulations, admissions and graduation requirements, course offerings, tuition, fees, and any other material set forth in its Bulletin or this Handbook at any time without prior notice. Changes become effective when posted on the official bulletin boards located on the second floor. Students should consult the designated bulletin boards at CSL for changes. TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION . 1 II. CALENDARS .......................................... 2 A: 1998-99 ACADEMIC CALENDAR . 2 B. COURSE SCHEDULE ................................ 6 C. CALENDAR OF EVENTS .............................. 6 III. FACILITIES ........................................... 7 A. Brookdale Center -- 55 Fifth Avenue . .. 7 B. Residence Hall . 7 C. Yeshiva University . -

Divorce Retainer Agreement

RETAINER AGREEMENT FOR_________________________________________________________________ BETWEEN FIRM NAME:__________________________________________________________ ADDRESS: ___________________________________________________________ CITY/STATE___________________________________________________________ TEL. NO.:_____________________________________________________________ AND CLIENT: _____________________________________________________________ ADDRESS: ___________________________________________________________ CITY/STATE: __________________________________________________________ TEL. NO.: ____________________________________________________________ This law firm will represent you with respect to legal problems concerning your marriage. We have discussed this firm’s representation of you. We have fully explained to you all services of our firm and your duties to our firm. LAWYER’S DUTIES 1. The primary duty of this firm will be to represent you in your matrimonial dispute. This firm will make all necessary preparations and, with your permission, aid you in retaining all necessary experts to resolve some or all of the following issues: (a) Custody (b) Visitation (c) Alimony (d) Child Support (e) Division of property (f) Allocation of counsel fees and costs (g) Other ____________________________________________ 2. This firm’s duties end upon entry of a final court order. This agreement will apply only to work to be performed by this firm at the trial level. If you wish to appeal the result after completion of the trial, we have to come to a new agreement. NO GUARANTEE 3. Judges are granted great discretion in matrimonial matters, so this firm cannot guarantee the results. REPRESENTATION BY THE FIRM 4. Any lawyer in the firm may be involved in your case. A partner will be in charge of managing your case. You may communicate with the partner in charge or with any of our other lawyers who may be handling your case. WITHDRAWAL BY LAWYER 5. (a) If you do not pay our bills on time, we shall be free to ask the court for permission to withdraw as your lawyer. -

New York Supreme Court APPELLATE DIVISION—FIRST DEPARTMENT

To Be Argued By: MARC E. ISSERLES New York County Clerk’s Index No. 113781/09 New York Supreme Court APPELLATE DIVISION—FIRST DEPARTMENT dSCAROLA ELLIS LLP, Plaintiff-Respondent, —against— ELAN PADEH, Defendant-Appellant. REPLY BRIEF FOR DEFENDANT-APPELLANT ALEXANDRA A.E. SHAPIRO MARC E. ISSERLES JAMES DARROW SHAPIRO, ARATO & ISSERLES LLP 500 Fifth Avenue, 40th Floor New York, New York 10110 (212) 257-4880 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Attorneys for Defendant-Appellant REPRODUCED ON RECYCLED PAPER TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF AUTHORITIES .......................................................................... ii PRELIMINARY STATEMENT .................................................................... 1 ARGUMENT .................................................................................................. 4 I. THE UNJUST ENRICHMENT CAUSE OF ACTION IS LEGALLY DEFICIENT AND SHOULD NOT HAVE GONE TO THE JURY ... 4 A. An Express Agreement Bars An Unjust Enrichment Claim Covering The Same Subject Matter ............................................... 4 B. Scarola’s “Correctly Calculated” Damages Theory Is Indefensible ..................................................................................... 9 C. Scarola’s Remaining Arguments Are Without Merit ................... 15 1. Padeh Specifically Challenged The Quasi-Contract Claims Below ............................................................................................ 15 2. Scarola Cannot Avoid A Valid Settlement By Calling It -

Cumulative Faculty Bibliography Through 2009 Fordham Law School Library

Fordham Law School FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History Faculty Bibliography Law Library September 2018 Cumulative Faculty Bibliography Through 2009 Fordham Law School Library Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/fac_bib Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Fordham Law School Library, "Cumulative Faculty Bibliography Through 2009" (2018). Faculty Bibliography. 13. https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/fac_bib/13 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Library at FLASH: The orF dham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Bibliography by an authorized administrator of FLASH: The orF dham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Fordham Law School Cumulative Faculty Bibliography Through 2009 ABRAHAM ABRAMOVSKY Books (Editor) Criminal Law and the Corporate Counsel. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1981. Journal Articles “Prosecuting Judges for Ethical Violations: Are Criminal Sanctions Constitutional and Prudent, or Do They Constitute a Threat to Judicial Independence?” 33 Fordham Urban Law Journal 727-773 (2006) [with Jonathan I. Edelstein] “Criminal Law Current Comment: People V. Suarez and Depraved Indifference Murder: The Court of Appeals' Incomplete Revolution.” 56 Syracuse Law Review 707-734 (2006) [with Jonathan I. Edelstein] ADepraved Indifference Murder Prosecutions in New York: Time for Substantive and Procedural Clarification.@ 55 Syracuse Law Review 455-494 (2005) (with Jonathan I. Edelstein). "The Drug War and the American Jewish Community: 1880 to 2002 and Beyond." 6 The Journal of Gender, Race & Justice 1-38 (2002 ) (with Jonathan I. -

In the Supreme Court of Georgia Decided

In the Supreme Court of Georgia Decided: September 8, 2020 S19G1026. INNOVATIVE IMAGES, LLC v. JAMES DARREN SUMMERVILLE, et al. NAHMIAS, Presiding Justice. Innovative Images, LLC (“Innovative”) sued its former attorney James Darren Summerville, Summerville Moore, P.C., and The Summerville Firm, LLC (collectively, the “Summerville Defendants”) for legal malpractice. In response, the Summerville Defendants filed a motion to dismiss the suit and to compel arbitration in accordance with the parties’ engagement agreement, which included a clause mandating arbitration for any dispute arising under the agreement. The trial court denied the motion, ruling that the arbitration clause was “unconscionable” and thus unenforceable because it had been entered into in violation of Rule 1.4 (b) of the Georgia Rules of Professional Conduct (“GRPC”) for attorneys found in Georgia Bar Rule 4-102 (d). In Division 1 of its opinion in Summerville v. Innovative Images, LLC, 349 Ga. App. 592 (826 SE2d 391) (2019), the Court of Appeals reversed that ruling, holding that the arbitration clause was not void as against public policy or unconscionable. See id. at 597-598. We granted Innovative’s petition for certiorari to review the Court of Appeals’s holding on this issue. As explained below, we conclude that regardless of whether Summerville violated GRPC Rule 1.4 (b) by entering into the mandatory arbitration clause in the engagement agreement without first apprising Innovative of the advantages and disadvantages of arbitration – an issue which we need not address – the clause is not void as against public policy because Innovative does not argue and no court has held that such an arbitration clause may never lawfully be included in an attorney-client contract. -

Judgment-Based Lawyering: Working in Coalition Mark Aaronson UC Hastings College of the Law, [email protected]

University of California, Hastings College of the Law UC Hastings Scholarship Repository Faculty Scholarship 2019 Judgment-Based Lawyering: Working in Coalition Mark Aaronson UC Hastings College of the Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/faculty_scholarship Recommended Citation Mark Aaronson, Judgment-Based Lawyering: Working in Coalition, 27 J. Affordable Housing 549 (2019). Available at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/faculty_scholarship/1718 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Judgment-Based Lawyering: Working in Coalition Mark Neal Aaronson I. In tro d uctio n ............................................................................................. 54 9 II. The Political and Professional Context ................................................ 552 III. Workin g in C oalition .............................................................................. 559 A . The H astings C ED C linic ................................................................ 559 B . W h o Is th e C lien t? ......................................... ................................... 560 C. M obilization and Collaboration .................................................... 562 D. The Development Agreement's Terms ........................................ -

(Rev. August 2005) Working Paper in Regulatory Studies

LOGOS Defining What to Regulate: Silica & the Problem of Regulatory Categorization Andrew P. Morriss & Susan E. Dudley CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF LAW Case Research Paper Series, No. __ (Rev. August 2005) MERCATUS CENTER AT GEORGE MASON UNIVERSITY Working Paper in Regulatory Studies ABSTRACT This article examines the history of human exposure to silica, the second most common element on earth, to explore the problem of categorizing substances for regulatory purposes and the role interest groups play in developing policy. The regulatory history of silica teaches three important lessons: First, the most compelling account of the cycle of action and inaction on the part of regulators is the one based on interest groups. Second, knowledge about hazards is endogenous – it arises in response to outside events, to regulations, and to interest groups. Accepting particular states of knowledge as definitive is thus a mistake, as is failing to consider the incentives for knowledge production created by regulatory measures. Third, the rise of the trial bar as an interest group means that the problems of silica exposure and similar occupational hazards cannot simply be left to the legal system to resolve through individual tort actions. We suggest that by understanding market forces, regulators can harness the energy of interest groups to create better solutions to addressing the problems of silica exposure, as well as other workplace health and safety issues. Defining What to Regulate: Silica & the Problem of Regulatory Categorization Andrew P. Morriss* & Susan E. Dudley** I. The Problem of Categorization................................................................................... 3 A. Characterization ...................................................................................................... 5 B. Silica Categorization and Health Effects ............................................................... -

A Rejoinder to Lester Brickman: on the Theory Class's Theories of Asbestos Litigation

Pepperdine Law Review Volume 32 Issue 4 Article 1 5-15-2005 A Rejoinder to Lester Brickman: On the Theory Class's Theories of Asbestos Litigation Charles Silver Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.pepperdine.edu/plr Part of the Legal History Commons, and the Torts Commons Recommended Citation Charles Silver A Rejoinder to Lester Brickman: On the Theory Class's Theories of Asbestos Litigation, 32 Pepp. L. Rev. Iss. 4 (2005) Available at: https://digitalcommons.pepperdine.edu/plr/vol32/iss4/1 This Response is brought to you for free and open access by the Caruso School of Law at Pepperdine Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Pepperdine Law Review by an authorized editor of Pepperdine Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected], [email protected]. A Rejoinder to Lester Brickman: On the Theory Class's Theories of Asbestos Litigation Charles Silver* INTRODUCTION In 2003, the Pepperdine Law Review hosted a conference on mass tort litigation and later published a symposium issue containing the articles pre- sented there. Professor Lester Brickman and I participated in a panel de- voted to legal ethics. I listened to Professor Brickman's spoken remarks, and I am certain he said nothing about me personally. I was therefore sur- prised to discover that an entire section of Professor Brickman's published article contained a personal attack on me. I was also dismayed to read a host of misstatements and misleading statements, none of which Professor Brickman attempted to verify by checking with me. -

Retainer Agreement This ATTORNEY

Retainer Agreement This ATTORNEY-CLIENT FEE CONTRACT ("Contract") is entered into by and between ("Client/Corporation") and JUN WANG & ASSOCIATES, P.C. ("Attorney"). 1. CONDITIONS. This Contract will not take effect, and Attorney will have no obligation to provide legal services, until Client returns a signed copy of this Contract and pays the deposit called for under paragraph 5. 2. SCOPE AND DUTIES. Client hires Attorney to provide legal services in connection with PERM Labor Certification Process for (Beneficiary) sponsored by (Employer). Attorney shall provide those legal services reasonably required to represent Client and shall take reasonable steps to keep Client informed of progress and to respond to Client's inquiries. Client shall be truthful with Attorney, cooperate with Attorney, keep Attorney informed of developments, abide by this Contract, pay Attorney's bills on time and keep Attorney advised of Client's address, telephone number and whereabouts. Attorney’s services in this matter will end, unless otherwise agreed upon in writing signed by Attorney, when there is a final agreement, settlement, decision or judgment by the court. 3. GUARANTEE OF PROFESSIONAL COMPETENCE. Attorney agrees to use due diligence in furthering Client’s best interests under the laws. Attorney is liable to Client for Attorney’s negligence or incompetence. However, Attorney makes on guarantee of the outcome of this representation. 4. LEGAL FEES AND EXPENSES. In consideration of the professional services rendered and to be rendered, the client agrees to pay the fee $4,000 as legal fee, plus costs and expenses. Client agrees to pay $50.00 administrative cost for bounced or stopped payment checks per transaction. -

Retaliatory RICO and the Puzzle of Fraudulent Claiming

Michigan Law Review Volume 115 Issue 5 2017 Retaliatory RICO and the Puzzle of Fraudulent Claiming Nora Freeman Engstrom Stanford Law School Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mlr Part of the Litigation Commons, and the Torts Commons Recommended Citation Nora Freeman Engstrom, Retaliatory RICO and the Puzzle of Fraudulent Claiming, 115 MICH. L. REV. 639 (2017). Available at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mlr/vol115/iss5/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Michigan Law Review at University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Michigan Law Review by an authorized editor of University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. RETALIATORY RICO AND THE PUZZLE OF FRAUDULENT CLAIMING Nora Freeman Engstrom* Over the past century, the allegation that the tort liability system incentivizes legal extortion and is chock-full of fraudulent claims has dominated public discussion and prompted lawmakers to ever-more-creatively curtail individu- als’ incentives and opportunities to seek redress. Unsatisfied with these con- ventional efforts, in recent years, at least a dozen corporate defendants have “discovered” a new fraud-fighting tool. They’ve started filing retaliatory RICO suits against plaintiffs and their lawyers and experts, alleging that the initia- tion of certain nonmeritorious litigation constitutes racketeering activity— while tort reform advocates have applauded these efforts and exhorted more “courageous” companies to follow suit. Curiously, though, all of this has taken place against a virtual empirical void. Is the tort liability system actually brimming with fraudulent claims? No one knows. -

Nonrefundable Retainers: Impermissible Under Fiduciary, Statutory and Contract Law

Fordham Law Review Volume 57 Issue 2 Article 1 1988 Nonrefundable Retainers: Impermissible Under Fiduciary, Statutory and Contract Law Lester Brickman Lawrence A. Cunningham Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/flr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Lester Brickman and Lawrence A. Cunningham, Nonrefundable Retainers: Impermissible Under Fiduciary, Statutory and Contract Law, 57 Fordham L. Rev. 149 (1988). Available at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/flr/vol57/iss2/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. It has been accepted for inclusion in Fordham Law Review by an authorized editor of FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Nonrefundable Retainers: Impermissible Under Fiduciary, Statutory and Contract Law Cover Page Footnote Professor of Law, Benjamin N. Cardozo School of Law. B.S. 1961, Carnegie-Mellon University; J.D. 1964, University of Florida; LL.M. 1965, Yale University. Associate, Cravath, Swaine & Moore, New York, New York. B.A. 1985, University of Delaware; J.D. magna cum laude 1988, Benjamin N. Cardozo School of Law. This article is available in Fordham Law Review: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/flr/vol57/iss2/1 NONREFUNDABLE RETAINERS: IMPERMISSIBLE UNDER FIDUCIARY, STATUTORY AND CONTRACT LAW LESTER BRICKMAN* LAWRENCE A. CUNNINGHAM** TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction .............................................. 150 I. The Lawyer as Fiduciary .................................. 153 A. Client's Right to Discharge............................ 155 B. Codification of Trust ................................... 156 C. Exceptions to the Discharge Right ..................... 157 D. Historic Development ................................. 160 1. Up to Martin v. -

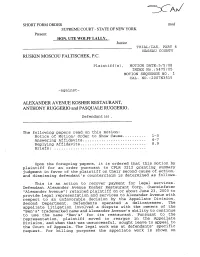

CPY Document

....... SHORT FORM ORDER mod SUPREME COURT - ST ATE OF NEW YORK Present: HON. UTE WOLFF LALLY. Justice TRIAL/lAS, PART NASSAU COUNTY RUSKIN MOSCOU FALTISCHEK, P. Plaintiff (s) , MOTION DATE: 5/5/08 INDEX No. : 5475/05 MOTION SEQUENCE No. CAL. NO. : 2007N3515 against- ALEXANDER A VENUE KOSHER RESTAURANT ANTHONY RUGGERIO and PASQUALE RUGGERIO, Defendant (s) . The following papers read on this motion: Notice of Motion/ Order to Show Cause. Answering Affidavits. Replying Affidavits. Briefs: Upon the foregoing papers, it is ordered that this motion by plaintiff for an order pursuant to CPLR 3212 granting sumary judgment in favor of the plaintiff on their second cause of action, and dismissing defendant I s counterclaim is determined as follows. This is an action to recover payment for legal services. Defendant Alexander Avenue Kosher Restaurant Corp. (hereinfater Alexander Avenue ) retained plaintiff on or about June 23, 2003 to provide legal representation and services to Alexander Avenue with respect to an unfavorable decision by the Appellate Division, Second Department. Defendants operated a delicatessen. The appellate litigation involved a dispute with the owners of the Ben " trademarked name and Alexander Avenue' s abili ty to continue to use the name " Ben for its restaurant. Pursuant to the representation, plaintiff moved to reargue in the Appellate Division, and when that was unsuccessful, sought leave to appeal the Court of Appeals. The legal work was at defendants ' specific request. For billing purposes the appellate work is shown on Ruskin v Alexander Avenue - 2 - Index No. 5475/05 plaintiff' s invoices, and referred to hereinafter as " Matter No.