An Anthropometric Face Model Using Variational Techniques

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Evolutionary History of the Human Face

This is a repository copy of The evolutionary history of the human face. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/145560/ Version: Accepted Version Article: Lacruz, Rodrigo S, Stringer, Chris B, Kimbel, William H et al. (5 more authors) (2019) The evolutionary history of the human face. Nature Ecology and Evolution. pp. 726-736. ISSN 2397-334X https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-019-0865-7 Reuse Items deposited in White Rose Research Online are protected by copyright, with all rights reserved unless indicated otherwise. They may be downloaded and/or printed for private study, or other acts as permitted by national copyright laws. The publisher or other rights holders may allow further reproduction and re-use of the full text version. This is indicated by the licence information on the White Rose Research Online record for the item. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ THE EVOLUTIONARY HISTORY OF THE HUMAN FACE Rodrigo S. Lacruz1*, Chris B. Stringer2, William H. Kimbel3, Bernard Wood4, Katerina Harvati5, Paul O’Higgins6, Timothy G. Bromage7, Juan-Luis Arsuaga8 1* Department of Basic Science and Craniofacial Biology, New York University College of Dentistry; and NYCEP, New York, USA. 2 Department of Earth Sciences, Natural History Museum, London, UK 3 Institute of Human Origins and School of Human Evolution and Social Change, Arizona State University, Tempe, AZ. -

Effects of Glans Penis Augmentation Using Hyaluronic Acid Gel for Premature Ejaculation

International Journal of Impotence Research (2004) 16, 547–551 & 2004 Nature Publishing Group All rights reserved 0955-9930/04 $30.00 www.nature.com/ijir Effects of glans penis augmentation using hyaluronic acid gel for premature ejaculation JJ Kim1, TI Kwak1, BG Jeon1, J Cheon1 and DG Moon1* 1Department of Urology, Korea University College of Medicine, Sungbuk-ku, Seoul, Korea The main limitation of medical treatment for premature ejaculation is recurrence after withdrawal of medication. We evaluated the effect of glans penis augmentation using injectable hyaluronic acid (HA) gel for the treatment of premature ejaculation via blocking accessibility of tactile stimuli to nerve receptors. In 139 patients of premature ejaculation, dorsal neurectomy (Group I, n ¼ 25), dorsal neurectomy with glandular augmentation (Group II, n ¼ 49) and glandular augmentation (Group III, n ¼ 65) were carried out, respectively. Two branches of dorsal nerve preserving that of midline were cut at 2 cm proximal to coronal sulcus. For glandular augmentation, 2 cc of HA was injected into the glans penis, subcutaneously. At 6 months after each procedure, changes of glandular circumference were measured by tapeline in Groups II and III. In each groups, ejaculation time, patient’s satisfaction and partner’s satisfaction were also assessed. There was no significant difference in preoperative ejaculation time among three groups. Preoperative ejaculation times were 89.2740.29, 101.54759.42 and 96.5752.32 s in Groups I, II and III, respectively. Postoperative ejaculation times were significantly increased to 235.6758.6, 324.247107.58 and 281.9793.2 s in Groups I, II and III, respectively (Po0.01). -

Standard Human Facial Proportions

Name:_____________________________________________ Date:__________________Period: __________________ Standard Human Facial Proportions: The standard proportions for the human head can help you place facial features and find their orientation. The list below gives an idea of ideal proportions. • The eyes are halfway between the top of the head and the chin. • The face is divided into 3 parts from the hairline to the eyebrow, from the eyebrow to the bottom of the nose, and from the nose to the chin. • The bottom of the nose is halfway between the eyes and the chin. • The mouth is one third of the distance between the nose and the chin. • The distance between the eyes is equal to the width of one eye. • The face is about the width of five eyes and about the height of about seven eyes. • The base of the nose is about the width of the eye. • The mouth at rest is about the width of an eye. • The corners of the mouth line up with the centers of the eye. Their width is the distance between the pupils of the eye. • The top of the ears line up slightly above the eyes in line with the outer tips of the eyebrows. • The bottom of the ears line up with the bottom of the nose. • The width of the shoulders is equal to two head lengths. • The width of the neck is about ½ a head. Facial Feature Examples.docx Page 1 of 13 Name:_____________________________________________ Date:__________________Period: __________________ PROFILE FACIAL PROPORTIONS Facial Feature Examples.docx Page 2 of 13 Name:_____________________________________________ Date:__________________Period: -

How to Create the Perfect Eyebrow

Creating the Perfect Brows . As a make-up artist, I was acutely aware of the fact that my mother had a need that conventional cosmetics could not meet. She suffered from a type of alopecia (hair loss) of the eyebrows and lashes ever since I could remember. I would draw the eyebrows on for her, but it was often a painstaking process for her to draw the eyebrows on herself on a daily basis. After my mom described the embarrassment of swimming and having the pencil wash off her eyebrows, and another afternoon when a neighbor stopped by after she had been napping and one eyebrow was completely wiped off when she answered the door, it clearly was time for a solution. After completing my certification with the Academy of Micropigmentation, I had one of the most fulfilling days of my life, the day I was able to give a gift of eyebrows to my mother. This was a life changing experience for her and an incredible boost to her self-image. She went on to do her eyeliner, which was especially beneficial to her due to the absence of eyelashes, and I was able to give her lips a fuller appearance with the permanent lipliner. It is said that the facial feature models spend the most time on is their eyebrows and most women, at some point, have altered their eyebrows by tweezing, waxing or electrolysis. As women grow older, the hair on the outer half of their brows tend to become sparse or even non-existent. In ancient China, royalty were the only ones adorned with “tattooed” eyebrows. -

Growth Hormone Deficiency Causing Micropenis:Peter A

Growth Hormone Deficiency Causing Micropenis:Peter A. Lee, MD, PhD, a Tom Mazur, PsyD, Lessons b Christopher P. Houk, MD, Learned c Robert M. Blizzard, MD d From a Well-Adjusted Adultabstract This report of a 46, XY patient born with a micropenis consistent with etiology from isolated congenital growth hormone deficiency is used to (1) raise the question regarding what degree testicular testosterone exposure aDepartment of Pediatrics, College of Medicine, Penn State to the central nervous system during fetal life and early infancy has on the University, Hershey, Pennsylvania; bCenter for Psychosexual development of male gender identity, regardless of gender of rearing; (2) Health, Jacobs School of Medicine and Biomedical suggest the obligatory nature of timely full disclosure of medical history; Sciences, University at Buffalo and John R. Oishei Children’s Hospital, Buffalo, New York; cDepartment of (3) emphasize that virtually all 46, XY infants with functional testes and Pediatrics, Medical College of Georgia, Augusta University, a micropenis should be initially boys except some with partial androgen Augusta, Georgia; and dDepartment of Pediatrics, College of Medicine, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, Virginia insensitivity syndrome; and (4) highlight the sustaining value of a positive long-term relationship with a trusted physician (R.M.B.). When this infant Dr Lee reviewed and discussed the extensive medical records with Dr Blizzard, reviewed presented, it was commonly considered inappropriate to gender assign an pertinent medical literature, and wrote each draft infant male whose penis was so small that an adult size was expected to be of the manuscript with input from all coauthors; inadequate, even if the karyotype was 46, XY, and testes were functional. -

Facial Image Comparison Feature List for Morphological Analysis

Disclaimer: As a condition to the use of this document and the information contained herein, the Facial Identification Scientific Working Group (FISWG) requests notification by e-mail before or contemporaneously to the introduction of this document, or any portion thereof, as a marked exhibit offered for or moved into evidence in any judicial, administrative, legislative, or adjudicatory hearing or other proceeding (including discovery proceedings) in the United States or any foreign country. Such notification shall include: 1) the formal name of the proceeding, including docket number or similar identifier; 2) the name and location of the body conducting the hearing or proceeding; and 3) the name, mailing address (if available) and contact information of the party offering or moving the document into evidence. Subsequent to the use of this document in a formal proceeding, it is requested that FISWG be notified as to its use and the outcome of the proceeding. Notifications should be sent to: Redistribution Policy: FISWG grants permission for redistribution and use of all publicly posted documents created by FISWG, provided the following conditions are met: Redistributions of documents, or parts of documents, must retain the FISWG cover page containing the disclaimer. Neither the name of FISWG, nor the names of its contributors, may be used to endorse or promote products derived from its documents. Any reference or quote from a FISWG document must include the version number (or creation date) of the document and mention if the document is in a draft status. Version 2.0 2018.09.11 Facial Image Comparison Feature List for Morphological Analysis 1. -

MR Imaging of Vaginal Morphology, Paravaginal Attachments and Ligaments

MR imaging of vaginal morph:ingynious 05/06/15 10:09 Pagina 53 Original article MR imaging of vaginal morphology, paravaginal attachments and ligaments. Normal features VITTORIO PILONI Iniziativa Medica, Diagnostic Imaging Centre, Monselice (Padova), Italy Abstract: Aim: To define the MR appearance of the intact vaginal and paravaginal anatomy. Method: the pelvic MR examinations achieved with external coil of 25 nulliparous women (group A), mean age 31.3 range 28-35 years without pelvic floor dysfunctions, were compared with those of 8 women who had cesarean delivery (group B), mean age 34.1 range 31-40 years, for evidence of (a) vaginal morphology, length and axis inclination; (b) perineal body’s position with respect to the hymen plane; and (c) visibility of paravaginal attachments and lig- aments. Results: in both groups, axial MR images showed that the upper vagina had an horizontal, linear shape in over 91%; the middle vagi- na an H-shape or W-shape in 74% and 26%, respectively; and the lower vagina a U-shape in 82% of cases. Vaginal length, axis inclination and distance of perineal body to the hymen were not significantly different between the two groups (mean ± SD 77.3 ± 3.2 mm vs 74.3 ± 5.2 mm; 70.1 ± 4.8 degrees vs 74.04 ± 1.6 degrees; and +3.2 ± 2.4 mm vs + 2.4 ± 1.8 mm, in group A and B, respectively, P > 0.05). Overall, the lower third vaginal morphology was the less easily identifiable structure (visibility score, 2); the uterosacral ligaments and the parau- rethral ligaments were the most frequently depicted attachments (visibility score, 3 and 4, respectively); the distance of the perineal body to the hymen was the most consistent reference landmark (mean +3 mm, range -2 to + 5 mm, visibility score 4). -

Study Guide Medical Terminology by Thea Liza Batan About the Author

Study Guide Medical Terminology By Thea Liza Batan About the Author Thea Liza Batan earned a Master of Science in Nursing Administration in 2007 from Xavier University in Cincinnati, Ohio. She has worked as a staff nurse, nurse instructor, and level department head. She currently works as a simulation coordinator and a free- lance writer specializing in nursing and healthcare. All terms mentioned in this text that are known to be trademarks or service marks have been appropriately capitalized. Use of a term in this text shouldn’t be regarded as affecting the validity of any trademark or service mark. Copyright © 2017 by Penn Foster, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of the material protected by this copyright may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the copyright owner. Requests for permission to make copies of any part of the work should be mailed to Copyright Permissions, Penn Foster, 925 Oak Street, Scranton, Pennsylvania 18515. Printed in the United States of America CONTENTS INSTRUCTIONS 1 READING ASSIGNMENTS 3 LESSON 1: THE FUNDAMENTALS OF MEDICAL TERMINOLOGY 5 LESSON 2: DIAGNOSIS, INTERVENTION, AND HUMAN BODY TERMS 28 LESSON 3: MUSCULOSKELETAL, CIRCULATORY, AND RESPIRATORY SYSTEM TERMS 44 LESSON 4: DIGESTIVE, URINARY, AND REPRODUCTIVE SYSTEM TERMS 69 LESSON 5: INTEGUMENTARY, NERVOUS, AND ENDOCRINE S YSTEM TERMS 96 SELF-CHECK ANSWERS 134 © PENN FOSTER, INC. 2017 MEDICAL TERMINOLOGY PAGE III Contents INSTRUCTIONS INTRODUCTION Welcome to your course on medical terminology. You’re taking this course because you’re most likely interested in pursuing a health and science career, which entails proficiencyincommunicatingwithhealthcareprofessionalssuchasphysicians,nurses, or dentists. -

Effects of Eye Position on Eigenface-Based Face Recognition Scoring Joe Marques Nicholas M

Effects of Eye Position on Eigenface-Based Face Recognition Scoring Joe Marques Nicholas M. Orlans Alan T. Piszcz The MITRE Corporation The MITRE Corporation The MITRE Corporation 7515 Colshire Drive 7515 Colshire Drive 7515 Colshire Drive McLean, VA 22102 McLean, VA 22102 McLean, VA 22102 1.703.883.6337 1.703.883.7454 1.703.883.7124 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] ABSTRACT successful template generation and proper matching or rejection Eigenface based facial recognition systems rely heavily on pre- of input faces. determined eye locations to properly orient the input face prior to template generation. Gross errors in the eye detection process can be identified by examining the reconstruction image of the resulting eigenspace representation. Subtle variation in the precision of eye finding that does not prevent subsequent enrollment has not been effectively studied or reported by the biometrics testing community. We quantify the impact of eye locations on face recognition match scores for identical subject images. The scores are analyzed to better understand the consequences and sensitivity of eye finding for more general applications when eye locations must be determined automatically. Figure 1 - Eye Position defined by a bounding box1 Categories and Subject Descriptors D.2.8 Metrics (performance metrics) Once eye locations are known, they are used as reference points General Terms to normalize the input image to some standardized scale and rotation. The center of the face is then masked to remove non- Measurement, Performance, Reliability, Experimentation, face regions such as the hair and neckline. Finally, the resulting Verification. image is projected into the multidimensional eigenspace[1] . -

OHA's Mask, Face Covering, and Face Shield Requirements for Health Care

OFFICE OF THE DIRECTOR Kate Brown, Governor 500 Summer St NE E20 Salem OR 97301 Voice: 503-947-2340 Date: June 30,2021 Fax: 503-947-2341 Mask, Face Covering, and Face Shield Requirements for Health Care Offices While the Governor has rescinded many of the Executive Orders, the declaration of emergency remains in effect and masks are still required in health care settings. See Executive Order 21-15. In addition, health care offices must continue to follow all applicable state and federal regulatory requirements related to masking, including Oregon-OSHA rules addressing COVID-19 workplace risks. Authority: ORS 433.441, ORS 433.443, ORS 431A.010 and ORS 431A.015 Applicability: These requirements apply to: • All health care personnel in health care offices, as defined below. • All patients and visitors in health care offices, as defined below. Definitions: • “Face covering” means a cloth, polypropylene, paper or other face covering that covers the nose and the mouth and that rests snugly above the nose, below the mouth, and on the sides of the face. • “Face mask” means a medical grade mask. • “Face shield” means a clear plastic shield that covers the forehead, extends below the chin, and wraps around the sides of the face. • “Healthcare Personnel (HCP)” means all paid and unpaid persons serving in healthcare offices who have the potential for direct or indirect exposure to patients or infectious materials, including body substances (e.g., blood, tissue, and specific body fluids); contaminated medical supplies, devices, and equipment; contaminated -

Glossary of Terms Related to Patient and Medication Safety

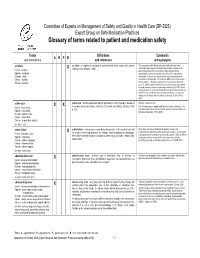

Committee of Experts on Management of Safety and Quality in Health Care (SP-SQS) Expert Group on Safe Medication Practices Glossary of terms related to patient and medication safety Terms Definitions Comments A R P B and translations and references and synonyms accident accident : an unplanned, unexpected, and undesired event, usually with adverse “For many years safety officials and public health authorities have Xconsequences (Senders, 1994). discouraged use of the word "accident" when it refers to injuries or the French : accident events that produce them. An accident is often understood to be Spanish : accidente unpredictable -a chance occurrence or an "act of God"- and therefore German : Unfall unavoidable. However, most injuries and their precipitating events are Italiano : incidente predictable and preventable. That is why the BMJ has decided to ban the Slovene : nesreča word accident. (…) Purging a common term from our lexicon will not be easy. "Accident" remains entrenched in lay and medical discourse and will no doubt continue to appear in manuscripts submitted to the BMJ. We are asking our editors to be vigilant in detecting and rejecting inappropriate use of the "A" word, and we trust that our readers will keep us on our toes by alerting us to instances when "accidents" slip through.” (Davis & Pless, 2001) active error X X active error : an error associated with the performance of the ‘front-line’ operator of Synonym : sharp-end error French : erreur active a complex system and whose effects are felt almost immediately. (Reason, 1990, This definition has been slightly modified by the Institute of Medicine : “an p.173) error that occurs at the level of the frontline operator and whose effects are Spanish : error activo felt almost immediately.” (Kohn, 2000) German : aktiver Fehler Italiano : errore attivo Slovene : neposredna napaka see also : error active failure active failures : actions or processes during the provision of direct patient care that Since failure is a term not defined in the glossary, its use is not X recommended. -

Software for Anthropometric Analysis of a Person Face⋆

Software for Anthropometric Analysis of a Person Face? Darya Panarina[0000−0001−7755−2629] ([email protected]), Pavel Balakshin[0000−0003−1916−9546] ([email protected]) ITMO University, Saint Petersburg, Russia Abstract. An accurate and quick assessment of psychological character- istics of a person is relevant in many areas of human activity, for example, in psychological research, education, coaching, career guidance, recruit- ment, etc. Scientific studies show that a face represents not only basic information about a person (age, race, etc.), but also some information about his state of health or individual psychological characteristics. In this study, a hypothesis was put forward that type of thinking expresses on facial features. This hypothesis was considered on the example of first and fourth year students of educational programs in the field of in- formation technology. Hypothesis testing was carried out using digital facial anthropometry methods. Therefore an application that performed anthropometric analysis of faces was developed. A database of students faces images was collected, the processing of which was carried out as follows. First, the program forms a collective image - an average model of a fourth-year student. After this, the models of first-year students faces were compared with this model-sample. The program gave out the per- centage of the models similarity as a result of comparison. Analysis of the obtained results showed the presence of similar facial features in first and fourth year students. The results of the study show possible direc- tions for further work on testing the hypothesis about the relationship between the type of thinking and facial features of a person.