The Latest Ebola Outbreaks: What Has Changed in the International and U.S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tuesday, September 24, 2019 Time: 6:00Pm – 8:00Pm Location: Delegates Dining Room (Private Dining Rooms 6 – 8) Please Email [email protected] to RSVP

The World Health Organization, the United Nations Development Programme and the Global Fund are pleased to invite you to a Side-Event to the High-Level Meeting on Universal Health Coverage: Anti-Corruption, Transparency and Accountability in Health. A multi-sectoral panel discussion will explore the impact of corruption on achieving Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 3, ensuring healthy lives and promoting wellbeing for all, with a specific focus on SDG 3.8, achieving universal health coverage (UHC). The discussion will consider how the ongoing establishment of an Anti-Corruption, Transparency and Accountability for Health Alliance (ACTA) can leverage its multi-stakeholder platform to foster coordination and collaboration, provide normative guidance to assist countries in developing strategies and partnerships to prevent health sector corruption, and contribute to interventions that strengthen the global pledge to leave no one behind. Date: Tuesday, September 24, 2019 Time: 6:00pm – 8:00pm Location: Delegates Dining Room (Private Dining Rooms 6 – 8) Please email [email protected] to RSVP. Due to limited seating, please confirm your attendance no later than Thursday, 19 September 2019. AGNÉS SOUCAT Director for Health Systems, Governance and Financing World Health Organization MANDEEP DHALIWAL DR. PETER SALAMA MARIJKE WIJNROKS Director of HIV, Health and Executive Director, Universal Health Coverage Chief of Staff Development Practice Life Course The Global Fund United Nations Development Programme World Health Organization JILLIAN KOHLER ALLAN MALECHE Professor, Leslie Dan Faculty of Pharmacy Executive Director University of Toronto KELIN DIWA SAMAD WILLIAM SAVEDOFF Deputy Minister of Policy and Planning Senior Fellow Ministry of Public Health Center for Global Development Afghanistan Mandeep Dhaliwal Director, HIV, Health and Development Team, Bureau of Policy and Programme Support United Nations Development Programme Mandeep Dhaliwal is the Director of UNDP’s HIV, Health and Development Group, Bureau of Policy and Programme Support. -

Of the United Nations Mission in the DRC / MONUC – MONUSCO

Assessing the of the United Nations Mission in the DRC / MONUC – MONUSCO REPORT 3/2019 Publisher: Norwegian Institute of International Affairs Copyright: © Norwegian Institute of International Affairs 2019 ISBN: 978-82-7002-346-2 Any views expressed in this publication are those of the author. Tey should not be interpreted as reflecting the views of the Norwegian Institute of International Affairs. Te text may not be re-published in part or in full without the permission of NUPI and the authors. Visiting address: C.J. Hambros plass 2d Address: P.O. Box 8159 Dep. NO-0033 Oslo, Norway Internet: effectivepeaceops.net | www.nupi.no E-mail: [email protected] Fax: [+ 47] 22 99 40 50 Tel: [+ 47] 22 99 40 00 Assessing the Efectiveness of the UN Missions in the DRC (MONUC-MONUSCO) Lead Author Dr Alexandra Novosseloff, International Peace Institute (IPI), New York and Norwegian Institute of International Affairs (NUPI), Oslo Co-authors Dr Adriana Erthal Abdenur, Igarapé Institute, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil Prof. Tomas Mandrup, Stellenbosch University, South Africa, and Royal Danish Defence College, Copenhagen Aaron Pangburn, Social Science Research Council (SSRC), New York Data Contributors Ryan Rappa and Paul von Chamier, Center on International Cooperation (CIC), New York University, New York EPON Series Editor Dr Cedric de Coning, NUPI External Reference Group Dr Tatiana Carayannis, SSRC, New York Lisa Sharland, Australian Strategic Policy Institute, Canberra Dr Charles Hunt, Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology (RMIT) University, Australia Adam Day, Centre for Policy Research, UN University, New York Cover photo: UN Photo/Sylvain Liechti UN Photo/ Abel Kavanagh Contents Acknowledgements 5 Acronyms 7 Executive Summary 13 Te effectiveness of the UN Missions in the DRC across eight critical dimensions 14 Strategic and Operational Impact of the UN Missions in the DRC 18 Constraints and Challenges of the UN Missions in the DRC 18 Current Dilemmas 19 Introduction 21 Section 1. -

Download File

UNICEF DRC | COVID-19 Situation Report COVID-19 Situation Report #9 29 May-10 June 2020 /Desjardins COVID-19 overview Highlights (as of 10 June 2020) 25702 • 4.4 million children have access to distance learning UNI3 confirmed thanks to partnerships with 268 radio stations and 20 TV 4,480 cases channels © UNICEF/ UNICEF’s response deaths • More than 19 million people reached with key messages 96 on how to prevent COVID-19 people 565 recovered • 29,870 calls managed by the COVID-19 Hotline • 4,338 people (including 811 children) affected by COVID-19 cases under 388 investigation and 837 frontline workers provided with psychosocial support • More than 200,000 community masks distributed 2.3% Fatality Rate 392 new samples tested UNICEF’s COVID-19 Response Kinshasa recorded 88.8% (3,980) of all confirmed cases. Other affected provinces including # of cases are: # of people reached on COVID-19 through North Kivu (35) South Kivu (89) messaging on prevention and access to 48% Ituri (2) Kongo Central (221) Haut RCCE* services Katanga (38) Kwilu (2) Kwango (1) # of people reached with critical WASH Haut Lomami (1) Tshopo (1) supplies (including hygiene items) and services 78% IPC** Equateur (1) # of children who are victims of violence, including GBV, abuse, neglect or living outside 88% DRC COVID-19 Response PSS*** of a family setting that are identified and… Funding Status # of children and women receiving essential healthcare services in UNICEF supported 34% Health facilities Funds # of caregivers of children (0-23 months) available* DRC COVID-19 reached with messages on breadstfeeding in 15% 30% Funding the context of COVID-19 requirements* : Nutrition $ 58,036,209 # of children supported with distance/home- 29% based learning Funding Education Gap 70% 0% 20% 40% 60% 80% 100% *Funds available include 9 million USD * Risk Communication and Community Engagement UNICEF regular ressources allocated by ** Infection Prevention and Control the office for first response needs. -

Bulletin of the World Health Organization

News WHO’s new emergencies programme bridges two worlds Peter Salama tells Fiona Fleck how the World Health Organization’s (WHO) new emergencies programme is changing the way the agency helps countries prepare for and respond to health crises. Q: WHO’s new health emergencies programme aims to create one single Peter Salama is leading the World Health Organization’s programme, with one workforce, one (WHO) efforts to reform its emergency work. He was budget, one set of rules and processes appointed Executive Director of WHO’s new Health and one clear line of authority. How Emergencies Programme at the level of Deputy will you do this with WHO’s governance Director-General last year. Before that, he held senior structure of seven entities: headquarters posts at the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) (HQ) plus six Regional Offices? including Regional Director for the Middle East and A: The programme has one work- North Africa, Global Coordinator for Ebola and Chief of force – and that is the critical point – one WHO set of people we can rely on in emergen- Peter Salama Global Health. Before joining UNICEF in 2002, Salama cies, whether they are at regional level was an epidemic intelligence service officer at the or at HQ, and, increasingly, we want International Emergency and Refugee Health Branch of the United States the heads of Country Offices to see Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and a visiting professor in nutrition themselves as an integral part of the at Tufts University in the United States of America. He has worked with Médecins programme with the same philosophy, Sans Frontières and Concern Worldwide in Asia and sub-Saharan Africa. -

Ebola: Democratic Republic of Congo

CRS INSIGHT Ebola: Democratic Republic of Congo Updated October 4, 2018 (IN10917) | Related Author Tiaji Salaam-Blyther | Tiaji Salaam-Blyther, Coordinator, Specialist in Global Health ([email protected], 7-7677) Monyai L. Chavers, Research Assistant ([email protected], 7-0829) On August 1, 2018, the World Health Organization (WHO) reported that a new Ebola outbreak was detected in the eastern part of the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), about one week after having declared that a separate outbreak had ended in the western part of the country. This new outbreak is occurring in North Kivu and Ituri provinces, the most populated provinces in DRC, where a humanitarian crisis affecting over 1 million displaced people is ongoing. Health workers have begun vaccinating people in the districts to control the spread of the disease, though armed conflict in the areas is complicating control efforts. As of October 2, 2018, 162 people have contracted Ebola in North Kivu and Ituri provinces (including 19 health workers), 106 of whom have died (3 of whom were health workers). This outbreak is the 10th Ebola outbreak in DRC since the disease was discovered in 1976, and it stands in stark contrast to the previous outbreak (Figure 1). The outbreak that began in May 2018 was contained and ended within two months after having infected 54 people, including 33 of whom died. In its second month, this outbreak has caused twice as many deaths and is continuing to spread. Issues complicating efforts to contain the current outbreak include the following: Conflict. In September 2018, clashes between rebels and government forces had forced WHO to temporarily suspend operations in Beni, the WHO operational base. -

Democratic Republic of the Congo – Ebola Outbreaks SEPTEMBER 30, 2020

Fact Sheet #10 Fiscal Year (FY) 2020 Democratic Republic of the Congo – Ebola Outbreaks SEPTEMBER 30, 2020 SITUATION AT A GLANCE 128 53 13 3,470 2,287 Total Confirmed and Total EVD-Related Total EVD-Affected Total Confirmed and Total EVD-Related Probable EVD Cases in Deaths in Équateur Health Zones in Probable EVD Cases in Deaths in Eastern DRC Équateur Équateur Eastern DRC at End of at End of Outbreak Outbreak MoH – September 30, 2020 MoH – September 30, 2020 MoH – September 30, 2020 MoH – June 25, 2020 MoH – June 25, 2020 Health actors remain concerned about surveillance gaps in northwestern DRC’s Équateur Province. In recent weeks, several contacts of EVD patients have travelled undetected to neighboring RoC and the DRC’s Mai- Ndombe Province, heightening the risk of regional EVD spread. Logistics coordination in Equateur has significantly improved in recent weeks, with response actors establishing a Logistics Cluster in September. The 90-day enhanced surveillance period in eastern DRC ended on September 25. TOTAL USAID HUMANITARIAN FUNDING USAID/BHA1,2 $152,614,242 For the DRC Ebola Outbreaks Response in FY 2020 USAID/GH in $2,500,000 Neighboring Countries3 For complete funding breakdown with partners, see funding chart on page 6 Total $155,114,2424 1USAID’s Bureau for Humanitarian Assistance (USAID/BHA) 2 Total USAID/BHA funding includes non-food humanitarian assistance from the former Office of U.S. Foreign Disaster Assistance. 3 USAID’s Bureau for Global Health (USAID/GH) 4 Some of the USAID funding intended for Ebola virus disease (EVD)-related programs in eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) is now supporting EVD response activities in Équateur. -

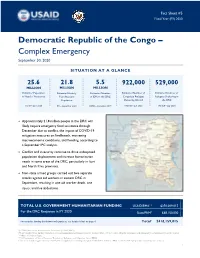

DRC Complex Emergency Fact Sheet #5 09.30.2020

Fact Sheet #5 Fiscal Year (FY) 2020 Democratic Republic of the Congo – Complex Emergency September 30, 2020 SITUATION AT A GLANCE 25.6 21.8 5.5 922,000 529,000 MILLION MILLION MILLION Estimated Population Estimated Acutely Estimated Number Estimated Number of Estimated Number of in Need of Assistance Congolese Refugees Refugees Sheltering in Food Insecure of IDPs in the DRC Population Sheltering Abroad the DRC OCHA – June 2020 UNHCR – July 2020 UNHCR – July 2020 IPC – September 2020 OCHA – December 2019 Approximately 21.8 million people in the DRC will likely require emergency food assistance through December due to conflict, the impact of COVID-19 mitigation measures on livelihoods, worsening macroeconomic conditions, and flooding, according to a September IPC analysis. Conflict and insecurity continue to drive widespread population displacement and increase humanitarian needs in some areas of the DRC, particularly in Ituri and North Kivu provinces. Non-state armed groups carried out two separate attacks against aid workers in eastern DRC in September, resulting in one aid worker death, one injury, and five abductions. TOTAL U.S. GOVERNMENT HUMANITARIAN FUNDING USAID/BHA1,2 $350,009,015 For the DRC Response in FY 2020 State/PRM3 $68,150,000 For complete funding breakdown with partners, see detailed chart on page 6 Total4 $418,159,015 1USAID’s Bureau for Humanitarian Assistance (USAID/BHA) 2 Total USAID/BHA funding includes non-food humanitarian assistance from the former Office of U.S. Foreign Disaster Assistance and emergency food assistance from the former Office of Food for Peace. 3 U.S. Department of State’s Bureau of Population, Refugees, and Migration (State/PRM) 4 This total includes approximately $23,833,699 in supplemental funding through USAID/BHA and State/PRM for COVID-19 preparedness and response activities. -

The GAVI Alliance

GLOBAL PROGRAM REVIEW The GAVI Alliance Global Program Review The World Bank’s Partnership with the GAVI Alliance Main Report and Annexes Contents ABBREVIATIONS .................................................................................................................................. V ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ........................................................................................................................ XI PROGRAM AT A GLANCE: THE GAVI ALLIANCE ............................................................................ XII KEY BANK STAFF RESPONSIBLE DURING PERIOD UNDER REVIEW ........................................ XIV GLOSSARY ......................................................................................................................................... XV OVERVIEW ........................................................................................................................................ XVII GAVI ALLIANCE MANAGEMENT RESPONSE .............................................................................. XXV WORLD BANK GROUP MANAGEMENT RESPONSE ................................................................... XXIX CHAIRPERSON’S SUMMARY ......................................................................................................... XXXI 1. THE WORLD BANK-GAVI PARTNERSHIP AND THE PURPOSE OF THE REVIEW ...................... 1 Evolution of GAVI ..................................................................................................................................................... -

WHO's Response to the 2018–2019 Ebola Outbreak in North Kivu and Ituri, the Democratic Republic of the Congo

WHO's response to the 2018–2019 Ebola outbreak in North Kivu and Ituri, the Democratic Republic of the Congo Report to donors for the period August 2018 – June 2019 2 | 2018-2019 North Kivu and Ituri Ebola virus disease outbreak: WHO report to donors © World Health Organization 2019 Some rights reserved. This work is available under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 IGO licence (CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO; https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/igo). Under the terms of this licence, you may copy, redistribute and adapt the work for non-commercial purposes, provided the work is appropriately cited, as indicated below. In any use of this work, there should be no suggestion that WHO endorses any specific organization, products or services. The use of the WHO logo is not permitted. If you adapt the work, then you must license your work under the same or equivalent Creative Commons licence. If you create a translation of this work, you should add the following disclaimer along with the suggested citation: “This translation was not created by the World Health Organization (WHO). WHO is not responsible for the content or accuracy of this translation. The original English edition shall be the binding and authentic edition”. Any mediation relating to disputes arising under the licence shall be conducted in accordance with the mediation rules of the World Intellectual Property Organization. The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of WHO concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. -

Situation Report

BUREAU FOR DEMOCRACY, CONFLICT, AND HUMANITARIAN ASSISTANCE (DCHA) OFFICE OF U.S. FOREIGN DISASTER ASSISTANCE (OFDA) Democratic Republic of the Congo – Complex Emergency Fact Sheet #15, Fiscal Year (FY) 2009 April 15, 2009 Note: The last fact sheet was dated April 2, 2009. KEY DEVELOPMENTS • In an April 2 U.N. report, U.N. Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon highlighted recent progress in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), including ongoing efforts to disband armed groups causing insecurity in eastern DRC and integrate factions into the Armed Forces of the DRC (FARDC). However, the U.N. Secretary-General cautioned that the situation remains tenuous and continues to require international involvement. • The U.N. Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) has noted an increase in targeted attacks in recent months against humanitarian staff, significantly hindering the provision of emergency relief commodities to conflict-affected populations. Since January 1, a total of 34 incidents have occurred, including 5 attacks between April 1 and 6. NUMBERS AT A GLANCE SOURCE North Kivu IDPs1 since August 2008 300,000 OCHA – January 2009 Total North Kivu IDPs 841,648 UNHCR2 – March 2009 Orientale IDPs since September 2008 207,000 OCHA – April 2009 Congolese Refugees since August 2008 63,000 UNHCR – March 2009 Total Congolese Refugees 340,000 UNHCR – December 2008 FY 2009 HUMANITARIAN FUNDING PROVIDED TO DATE USAID/OFDA Assistance to DRC................................................................................................................ $14,026,517 USAID/FFP3 Assistance to DRC................................................................................................................... $51,455,600 State/PRM4 Assistance to DRC..................................................................................................................... $18,148,622 Total USAID and State Assistance to DRC.................................................................................................. $83,630,739 CURRENT SITUATION • On April 1, the U.N. -

The Exacerbation of Ebola Outbreaks by Conflict in the Democratic Republic of the Congo

The exacerbation of Ebola outbreaks by conflict in the Democratic Republic of the Congo Chad R. Wellsa,1, Abhishek Pandeya,1, Martial L. Ndeffo Mbahb, Bernard-A. Gaüzèrec, Denis Malvyc,d,e, Burton H. Singerf,2, and Alison P. Galvania aCenter for Infectious Disease Modeling and Analysis, Yale School of Public Health, New Haven, CT 06520; bDepartment of Veterinary Integrative Biosciences, College of Veterinary Medicine and Biomedical Sciences, Texas A&M University, College Station, TX 77843; cCentre René Labusquière, Department of Tropical Medicine and Clinical International Health, University of Bordeaux, 33076 Bordeaux, France; dDepartment for Infectious and Tropical Diseases, University Hospital Centre of Bordeaux, 33075 Bordeaux, France; eINSERM 1219, University of Bordeaux, 33076 Bordeaux, France; and fEmerging Pathogens Institute, University of Florida, Gainesville, FL 32610 Contributed by Burton H. Singer, September 9, 2019 (sent for review August 14, 2019; reviewed by David Fisman and Seyed Moghadas) The interplay between civil unrest and disease transmission is not recombinant vesicular stomatitis virus–Zaire Ebola virus vaccine well understood. Violence targeting healthcare workers and Ebola (13). The vaccination campaign not only played an important treatment centers in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) role in curtailing the epidemic expeditiously (14), it also facili- has been thwarting the case isolation, treatment, and vaccination tated public awareness of the disease and improved practice of efforts. The extent to which conflict impedes public health re- Ebola safety precautions (15). By contrast, the sociopolitical sponse and contributes to incidence has not previously been crisis in eastern DRC has hampered the contact tracing that is a evaluated. -

Geographic Access to Health Facilies in North and South Kivu, Democrac

INTRODUCTION Geographic Access to Health The Democratic Republic of the Congo has experienced a decade Facilies in North and South Kivu, of conflict that has decimated health infrastructure. In much of the country, access to health sites Democrac Republic of the Congo requires a 1‐2 day walk without FINDINGS AND LIMITATIONS North Kivu roads. In the Kivus, at the epicen‐ ter of the humanitarian crisis and The analysis of the raster and town rankings found two things: first, it funding, and with the largest pop‐ identified specific physical areas (shown in shades of red and blue on left ulation outside of Kinshasa, access map) that are either accessible or inaccessible to health facilities, given lack of roads, high slope of terrain and physical distance from health struc‐ Villages in the is better but still severely lacking. Kivus ranked by While lack of data prevents us tures. The same is visualized in more detail for specific towns on the map accessibility to from knowing the type or quality on right. The two together provide a good guide to which villages and re‐ health structures of care provided at each site, with gions in the Kivus are least accessible to existing health structures. GIS we can analyze the physical There was a strong correlation between existing towns, road networks accessibility of villages to health and health structures, but a few areas (southeast area of South Kivu) did structures in North and South Kivu not correlate, suggesting either incomplete health site data or lack of ac‐ provinces. cess. If we had greater confidence in the data we could assert that these villages do not have adequate access to health facilities.