5.2 Temple Architecture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Construction Techniques of Indian Temples

International Journal of Research in Engineering, Science and Management 420 Volume-1, Issue-10, October-2018 www.ijresm.com | ISSN (Online): 2581-5782 Construction Techniques of Indian Temples Chanchal Batham1, Aatmika Rathore2, Shivani Tandon3 1,3Student, Department of Architecture, SDPS Women’s College, Indore, India 2Assistant Professor, Department of Architecture, SDPS Women’s College, Indore, India Abstract—India is a country of temples. Indian temples, which two principle axis, which in turn resulted in simple structural are standing with an unmatched beauty and grandeur in the wake systems and an increased structural strength against seismic of time against the forces of nature, are the living evidences of forces. The Indian doctrine of proportions is designed not only structural efficiency and technological skill of Indian craftsman to correlate the various parts of building in an aesthetically and master builders. Every style of building construction reflects pleasing manner but also to bring the entire building into a a clearly distinctive basic principle that represents a particular culture and era. In this context the Indian Hindu temple magical harmony with the space. architecture are not only the abode of God and place of worship, B. Strutural Plan Density but they are also the cradle of knowledge, art, architecture and culture. The research paper describes the analysis of intrinsic Structural plan density defined as the total area of all vertical qualities, constructional and technological aspects of Indian structural members divided by the gross floor area. The size and Temples from any natural calamities. The analytical research density of structural elements is very great in the Indian temples highlights architectural form and proportion of Indian Temple, as compared to the today's buildings. -

Temples Name Sates Vaishno Devi Jammu & Temple, Kashmir Dedicated to Shakti, Mata Rani Badrinath Temple Uttarakhand Kedarnath Temple Uttarakhand

Temples Name Sates Vaishno Devi Jammu & Temple, Kashmir Dedicated to Shakti, Mata Rani Badrinath Temple Uttarakhand Kedarnath Temple Uttarakhand Golden Temple Amritsar, Punjab Markandeshwar Temple Haryana Hadimba devi Temple Himachal Pradesh Laxminarayan Temple ( New Delhi Birla Mandir ) Dilwara Temple Mount Abu, Rajasthan Kashi Vishwanath Temple- Varanasi, Uttar Dedicated to Lord Ganesha Pradesh Swaminarayan Akshardhan Delhi Temple Mahabodhi Temple Bodhgaya , Bihar Dakshnineswar kali Temple Kolkata Jagannath Temple - Puri, Odisha Dedicated to Jagannath God Kandariya Mahadev Madhya Temple- Part of Pradesh Khajuraho Temple Somnath Gujarat (Saurashtra ) Temple Siddhivinayak Temple- Located in Dedicated to Lord Ganesha Prabhadevi, Mumbai Maharashtra Balaji Venkateshwara Andhra Swamy Temple- Dedicated Pradesh to Lord Venkateshwara Lord Karnataka kalabhairah wara Temple Shi Dharmasthala Karnataka Manjunatheswara Temple Shi Dharmasthala Karnataka Manjunatheswara Temple Mureshwar Temple Karnataka Virupaksha Temple Karnataka Gomateshwara Bahubali Karnataka Temple Nataraja Temple- Tamil Nadu Dedicated to Lord Shiva Brihadeshwara Temple Thanjavur,Ta mil Nadu Jumbukeshwarar Temple Tamil Nadu Ranganathaswamy Temple- Tamil Nadu Dedicated to Lord Shiva Ekambareswarar Temple Kanchipuram, Tamil Nadu Sripuram Golden Temple- Vellore, Tamil Dedicated to Lord Shiva Nadu Padmanabhaswa Kerala my Temple Richest Temple of the world Sabarimala Temple Kerala Sukreswar Temple- Dedcated Assam to Lord Shiva Kamakhya Temple Assam Angkor Wat Temple- Largest Cambodia -

Regional Tourism Satellite Account, Rajasthan, 2009-10

Regional Tourism Satellite Account Rajasthan, 2009-10 Study Commissioned by the Ministry of Tourism, Government of India Prepared By National Council of Applied Economic Research 11, I. P. Estate, New Delhi, 110002 © National Council of Applied Economic Research, 2014 All rights reserved. The material in this publication is copyrighted. NCAER encourages the dissemination of its work and will normally grant permission to reproduce portions of the work promptly. For permission to photocopy or reprint any part of this work, please send a request with complete information to the publisher below. Published by Anil Kumar Sharma Acting Secretary, NCAER National Council of Applied Economic Research (NCAER) Parisila Bhawan, 11, Indraprastha Estate, New Delhi–110 002 Email: [email protected] Disclaimer: The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Governing Body of NCAER. Regional Tourism Satellite Account–Rajasthan, 2009-10 STUDY TEAM Project Leader Poonam Munjal Senior Advisor Ramesh Kolli Core Research Team Rachna Sharma Amit Sharma Monisha Grover Praveen Kumar Shashi Singh i Regional Tourism Satellite Account–Rajasthan, 2009-10 ii Regional Tourism Satellite Account–Rajasthan, 2009-10 PREFACE Tourism is as important an economic activity at sub-national level as it is at national level. In a diverse country like India, it is worthwhile assessing the extent of tourism within each state through the compilation of State Tourism Satellite Account (TSA). The scope of State TSAs goes beyond that of a national TSA as it provides the direct and indirect contribution of tourism to the state GDP and employment using state-specific demand and supply-side data. -

Mughal Empire

www.gradeup.co www.gradeup.co HISTORY Chronology of Important Events in Indian History ANCIENT INDIA Year Event Importance 2 Million BC to 10,00 BC Paleolithic Period Fire was discovered 2 Million BC to 50,000 BC Lower Paleolithic Tools made of limestones were 50,000 BC to 40,000 BC Middle Paleolithic used. They are found in 40,000 BC to 10,000 BC Upper Paleolithic Chotanagpur plateau and Kurnool district From 10,000 BC The Mesolithic Age Hunters and Herders Microlith tools were used 7000 BC The Neolithic age Food producers Use of polished tools Pre-Harappan Phase – 3000 BC Chalcolithic Age Use of Copper – first metal 2500 BC Harappan Phase Bronze age civilization, development of Urban culture 1500 BC-1000 BC Early Vedic period Rig Veda period 1000BC-500BC Later Vedic period Growth of 2nd Urban phase with the establishment of Mahajanapadhas 600 BC – 325 BC Mahajanapadhas 16 kingdoms with certain republics established 544 BC – 412 BC Haryanka Dynasty Bimbisara, Ajatshatru and Udayin 412 BC – 342 BC Shisunaga Dynasty Shisunaga and Kalashoka 344BC – 323 BC Nanda Dynasty Mahapadmananda 563 BC Birth of Gautama Buddha Buddhism established 540 BC Birth of Mahavira 24th Tirthankara of Jainism 518 BC Persian Invasion Darius 483 BC 1st Buddhist council Rajgir 383 BC 2nd Buddhist Council Vaishali 326 BC Macedonian Invasion Direct contact between Greek and India 250 BC 3rd Buddhist council Pataliputra www.gradeup.co 322 BC – 185 BC Mauryan Period Political unification of India, 322 BC – 298 BC Chandragupta Maurya Dhamma policy of Ashoka, the 298 BC -

The Temple Architecture in Odisha

ISSN 0970-8669 Odisha Review The Hindu temple architecture reflects a synthesis is concentrated in the city of Bhubaneswar where of arts, the ideals of religion, beliefs, values and there are over thirty of them. the way of life cherished under Hinduism. The temple is a place for pilgrimage. All the cosmic The main temples of this style consist of elements that create and celebrate life in Hindu the Lingaraja Temple at Bhubaneswar th pantheon are present in a Hindu temple from fire (11 century), the Jagannath temple at Puri th to water, from images of nature to deities, from (12 century) the Great Sun Temple at Konark the feminine to the masculine, from karma to (13th century), Rajarani Temple (10th century), artha. The form and meanings of architectural Mukteswar (10th Century), Parshuram Temple elements in a Hindu temple are designed to (8th Century) etc. function as the place where it is the link between The Kanlingan style consists of three man and the divine, to help his progress to spiritual distinct types of temples Rekha Deula, Pidha knowledge and truth, his liberation is called Deula and Khakhara Deula. The former two are Moksha. associated with Vishnu, Surya and Shiva temples The Temple Architecture in Odisha Sujata Routray The Indian temples are broadly divided while the third is mainly with Chamunda and Durga into Nagara, Vesara, Dravida and Gadag styles temples. The Rekha Deula and Khakhara Deula of architecture. However the temple architecture houses the sanctum sanctorum while the Pidha of Odisha corresponds to altogether a different Deula constitutes outer dancing and offering halls. -

Medieval India

A History of Knowledge Oldest Knowledge What the Jews knew What the Sumerians knew What the Christians knew What the Babylonians knew Tang & Sung China What the Hittites knew Medieval India What the Persians knew What the Japanese knew What the Egyptians knew What the Muslims knew What the Indians knew The Middle Ages What the Chinese knew Ming & Manchu China What the Greeks knew The Renaissance What the Phoenicians knew The Industrial Age What the Romans knew The Victorian Age What the Barbarians knew The Modern World 1 Medieval India Piero Scaruffi 2004 2 What the Indians knew • Bibliography – Gordon Johnson: Cultural Atlas of India (1996) – Henri Stierlin: Hindu India (2002) – Hermann Goetz: The Art of India (1959) – Heinrich Zimmer: Philosophies of India (1951) – Surendranath Dasgupta: A History of Indian Philosophy (1988) – Richards, John: The Mughal Empire (1995) 3 India • 304 BC - 184 BC: Maurya • 184 BC - 78 BC: Sunga • 78 AD -233: Kushan • 318 - 528: Gupta • 550 - 1190 : Chalukya • Hoysala (1020-1342) • 1192-1526: Delhi sultanate • 1526-1707: Moghul • 1707-1802: Maratha 4 What the Indians knew • Tantra – Ancient practice to worship the mother goddess through sexual intercourse – Group intercourse 5 What the Indians knew • Tantra – Esoteric Hinduism – Dialogues between the god Shiva and his wife Parvati – Reversals of Hindu social practices (e.g., incest) – Reversals of physiological processes – Forbidden substances are eaten and forbidden sexual acts are performed ritually – ”Five m's": maithuna ("intercourse"), matsya ("fish"), -

Iasbaba's 60 Days Plan – Day 35 (History)

IASbaba’s 60 Days Plan – Day 35 (History) 2018 Q.1) Consider the following pairs. Sculpture Material made from 1. Mother goddess Stone 2. Bearded priest Terracotta 3. Dancing girl Copper Which of the above pairs is/are correctly matched? a) 1 and 3 only b) 3 only c) All the above d) None Q.1) Solution (d) Terracotta: Terracotta figures are more realistic in Gujarat sites and Kalibangan. Toy carts with wheels, whistles, rattles, bird and animals, gamesmen, and discs were also rendered in terracotta. The most important terracotta figures are those represent Mother Goddess. Stone Statues: Stone statues found in Indus valley sites are excellent examples of handling the 3D volume. Two major stone statues are: Bearded Man (Priest Man, Priest-King) and Male Torso Bronze Casting: Bronze casting was practiced in wide scale in almost all major sites of the civilization. The technique used for Bronze Casting was Lost Wax Technique. Dancing girl and bull from Mohenjo-Daro. Do you know? Thousands of seals were discovered from the sites, usually made of steatite, and occasionally of agate, chert, copper, faience and terracotta, with beautiful figures of animals such as unicorn bull, rhinoceros, tiger, elephant, bison, goat, buffalo, etc. Some seals were also been found in Gold and Ivory. THINK! 1 IASbaba’s 60 Days Plan – Day 35 (History) 2018 Harappan pottery. Q.2) Arrange the following parts of stupa from top to bottom. 1. Yasti 2. Harmika 3. Chatras 4. Anda Select the correct answer using the codes given below. a) 3-1-2-4 b) 3-2-1-4 c) 2-3-1-4 d) 2-1-3-4 Q.2) Solution (a) Stupa dome is called as Anda. -

Mount Abu, Dilwara Temples: Vimala Vasahi

Mount Abu, Dilwara Temples: Vimala Vasahi Photographs from the American Institute of Indian Studies Produced by the Shraman Foundation About this book / virtual exhibition The group of Jain temples at Dilwara on Mount Abu, in southwestern Rajasthan, is celebrated for the astoundingly detailed marble sculpture that covers nearly every inch of the temples’ interiors. Using photographs in the collection of the American Institute of Indian Studies, this book [/ virtual exhibition] explores the oldest of these temples, the Vimala Vasahi. By tradition the temple was founded between 1031 and 1032 C.E., though most of the building we see today was constructed in the mid- twelfth century and repaired in the early fourteenth. Text by Katherine Kasdorf. Additional research by Andrew More. Photographs copyright of the American Institute of Indian Studies. © 2014 Shraman South Asian Museum and Learning Center Foundation Mount Abu, Dilwara Temple Complex, Vimala Vasahi Temple AIIS 030209 © American Institute of Indian Studies The subdued exterior of the Vimala Vasahi on Mount Abu starkly contrasts with the temple’s opulent interior. Here, tucked into the close space of the Dilwara temple compound, we catch a glimpse of the walls that surround the oldest temple of the group, built largely in the mid-twelfth century. Beneath the shallow domes seen in the middle of the photograph are the temple’s famous sculptural ceilings; each pinnacle seen along the peripheral wall marks the sacred space of a Jina enshrined within the courtyard’s subsidiary shrines. The stepped pyramidal towers of the temple’s enclosed hall and sanctum rise above the surrounding structures, marking the importance of the spaces below in the ritual hierarchy of the temple. -

Art Elsewhere During Medieval Period

Indian art From Indus valley to India today Talk 8 Art elsewhere during medieval period G Chandrasekaran S Swaminathan Following the golden track of the Gupta-s in the north It was Harshavardhana (7th century CE) who took over the mantle of the Guptas in the North. Along with his contemporaries in the Deccan, the Chalukyas and in the South, the Pallavas and the Rashtrakutas the period is truly momentous. Harshavardhana, a man of letters as vouched by the three plays written by him Nagananda, Ratnavali and Priyadarshika, he was a man of arts too. Harshavardhana, 7th century CE The pearl-bedecked, the elegantly braid-decorated with pearls, flowers and sprigs, the curls nestling on the forehead, the dreamy eyes, and the transparent dress with its neat embroidery make it one of the finest creations of the Indian sculptor's chisel. Panduvamsi, 6th-7th century CE Dedicated to Vishnu this post-Gupta most developed brick temple of India, retains most of its original appearance. It is unsurpassed in the richness and refinement of its ornament Sanctum door Lakshmana Temple, Sirpur, Chhattisgarh Gurjara Pratihara, 8th century CE The period of the Rajput clan Gurajara Pratihara-s is important for it covered wide area (Gangetic plain, Gujarat and Rajasthan) and long period (8th to 10th centuries). Head of Vishnu as Vaikuntha with a lion-face and a boar-face on either side, still retails the Gupta grace. Gurjara Pratihara, 8th century CE The Dancing Siva has been popular all over the country. This composition of a ten-armed Nataraja dancing in the lalita mode with gana-s holding musical instruments is of great interest. -

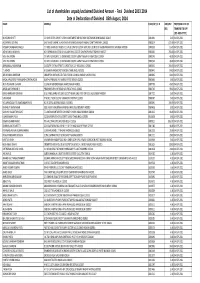

Final Dividend 2013-2014

List of shareholders unpaid/unclaimed Dividend Amount - Final Dividend 2013 -2014 Date of Declaration of Dividend : 05th August, 2014 NAME ADDRESS FOLIO/DP_CL ID AMOUNT PROPOSED DATE OF (RS) TRANSFER TO IEPF ( DD-MON-YYYY) MUKESH B BHATT C O SHRI DEVEN JOSHI 7 SURBHI APARTMENT NEHRU PARK VASTRAPUR AHMEDABAD 380015 0001091 8.0004-SEP-2021 AGGARWAL DEV RAJ SHIV SHAKTI SADAN 14 ASHOK VIHAR MAHESH NAGAR AMBALA CANTT HARYANA 134003 0000014 672.0004-SEP-2021 ROSHAN DADIBA ARSIWALLA C O MISS SHIRIN OF CHOKSI F 2 DALAL ESTATE F BLOCK GROUND FLOOR DR D BHADKAMKAR ROAD MUMBAI 400008 0000158 16.0004-SEP-2021 ACHAR MAYA MADHAV NO 9 BRINDAVAN 353 B 10 VALLABH BHAG ESTATE GHATKOPAR EAST BOMBAY 400077 0000030 256.0004-SEP-2021 YASH PAL ARORA C O MR K L MADAN C 19 DAYANAND COLONY LAJPAT NAGAR IV NEW DELHI 110024 0000343 48.8004-SEP-2021 YASH PAL ARORA C O MR K L MADAN C 19 DAYANAND COLONY LAJPAT NAGAR IV NEW DELHI 110024 0000344 48.8004-SEP-2021 ANNAMALAL RABINDRAN 24 SOUTH CHITRAI STREET C O POST BOX 127 MADURAI 1 625001 0000041 256.0004-SEP-2021 T J ASHOK M 51 ANNA NAGAR EAST MADRAS TAMIL NADU 600102 0000441 84.0004-SEP-2021 ARUN BABAN AMBEKAR CROMPTON GREAVES LTD TOOL ROOM A 3 MIDC AMBAD NASIK 422010 0000445 40.0004-SEP-2021 MAZHUVANCHERY PARAMBATH KORATHJACOB ILLATHU PARAMBU AYYAMPILLY PORT KERALA 682501 0005464 8.0004-SEP-2021 ALKA TUKARAM CHAVAN 51 5 NEW MUKUNDNAGAR AHMEDNAGAR 414001 0000709 40.0004-SEP-2021 ANGOLKAR SHRIKANT B PRABHU KRUPA M F ROAD NOUPADA THANE 400602 0000740 98.0004-SEP-2021 MIRZA NAWSHIR HOSHANG D 52 PANDURANG HOUSING SOCIETY -

Laxmi Devi Temple: Hoysala

Laxmi Devi Temple: Hoysala drishtiias.com/printpdf/laxmi-devi-temple-hoysala Why in News Recently, a Hoysala-era idol of Goddess Kali of the Lakshmi Devi Temple at Doddagaddavalli, Karnataka has been found damaged. Key Points Lakshmi Devi Temple: Lakshmi Devi temple was built by the Hoysalas in the year 1114 CE during the rule of king Vishnuvardhana. The building material is Chloritic schist, more commonly known as soapstone. The temple does not stand on a jagati (platform), a feature which became popular in later Hoysala temples. The temple is a chatuskuta construction (4 shrine and tower). The towers are in Kadamba nagara style. The mantapa is open and square. The reason for the square plan is the presence of shrines on all four sides of the mantapa. There is a separate fifth shrine of Bhairava, an avatar of Lord Shiva. The main deity is Goddess Lakshmi whereas all Hoysala temples are dedicated to either Lord Vishnu, Lord Shiva and in some cases to Jains. An archaeological Survey of India (ASI) monument and is also among the monuments proposed for the UNESCO World Heritage Site. 1/4 2/4 Hoysala Temple Architecture: It is the building style developed under the rule of the Hoysalas and is mostly concentrated in southern Karnataka. Hoysala temples are sometimes called hybrid or vesara as their unique style seems neither completely dravida nor nagara, but somewhere in between. They are easily distinguishable from other medieval temples by their highly original star-like ground-plans and a profusion of decorative carvings. The temples, instead of consisting of a simple inner chamber with its pillared hall, contain multiple shrines grouped around a central pillared hall and laid out in the shape of an intricately-designed star. -

The Role of Five Elements of Nature in Temple Architecture Ar

International Journal of Scientific & Engineering Research Volume 8, Issue 7, July-2017 1149 ISSN 2229-5518 The Role of Five Elements of Nature In Temple Architecture Ar. Snigdha Chaudhary Abstract— Examine the extensive influence of the selected theories of nature in Architecture namely element of nature effects the role of five ele- ments in Temple Architecture. “Theory of five elements of nature in context to the Temple Architectural Design ‘To make student understand the basic principles of five elements of nature so that it forms the basics for study of temple design through these topics.One should have a reasonable under- standing of its operational and economic implications, and lastly “To Evaluate the understanding of the relationship between space and design through five elements of nature’’ with the help of Hindu Temple Architecture. Index Terms— Temple architecture, five elements of nature, human perception of architectural expression, and temple concept through cosmology and philosophy —————————— —————————— 1 INTRODUCTION NDIA is well known for its rich heritage and variety of India, however while the basic elements of the temple are the I culture. Temples have always played an important role in same, the form and scale varied. For example as in the case of India's history and culture. There are more than 6 lakh the architectural elements like Sikhara (pyramidical roofs) and temples in India and about 1,80,000 temples in South India. Gopurams (the gateways). India is not only famous for various states but also for the cultures and such historic background that the past still has 2 ELEMENTS OF HINDU TEMPLE so much power on the present world.