Australian Sea Lion Management Strategy 2010

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rodondo Island

BIODIVERSITY & OIL SPILL RESPONSE SURVEY January 2015 NATURE CONSERVATION REPORT SERIES 15/04 RODONDO ISLAND BASS STRAIT NATURAL AND CULTURAL HERITAGE DIVISION DEPARTMENT OF PRIMARY INDUSTRIES, PARKS, WATER AND ENVIRONMENT RODONDO ISLAND – Oil Spill & Biodiversity Survey, January 2015 RODONDO ISLAND BASS STRAIT Biodiversity & Oil Spill Response Survey, January 2015 NATURE CONSERVATION REPORT SERIES 15/04 Natural and Cultural Heritage Division, DPIPWE, Tasmania. © Department of Primary Industries, Parks, Water and Environment ISBN: 978-1-74380-006-5 (Electronic publication only) ISSN: 1838-7403 Cite as: Carlyon, K., Visoiu, M., Hawkins, C., Richards, K. and Alderman, R. (2015) Rodondo Island, Bass Strait: Biodiversity & Oil Spill Response Survey, January 2015. Natural and Cultural Heritage Division, DPIPWE, Hobart. Nature Conservation Report Series 15/04. Main cover photo: Micah Visoiu Inside cover: Clare Hawkins Unless otherwise credited, the copyright of all images remains with the Department of Primary Industries, Parks, Water and Environment. This work is copyright. It may be reproduced for study, research or training purposes subject to an acknowledgement of the source and no commercial use or sale. Requests and enquiries concerning reproduction and rights should be addressed to the Branch Manager, Wildlife Management Branch, DPIPWE. Page | 2 RODONDO ISLAND – Oil Spill & Biodiversity Survey, January 2015 SUMMARY Rodondo Island was surveyed in January 2015 by staff from the Natural and Cultural Heritage Division of the Department of Primary Industries, Parks, Water and Environment (DPIPWE) to evaluate potential response and mitigation options should an oil spill occur in the region that had the potential to impact on the island’s natural values. Spatial information relevant to species that may be vulnerable in the event of an oil spill in the area has been added to the Australian Maritime Safety Authority’s Oil Spill Response Atlas and all species records added to the DPIPWE Natural Values Atlas. -

Special Issue3.7 MB

Volume Eleven Conservation Science 2016 Western Australia Review and synthesis of knowledge of insular ecology, with emphasis on the islands of Western Australia IAN ABBOTT and ALLAN WILLS i TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ABSTRACT 1 INTRODUCTION 2 METHODS 17 Data sources 17 Personal knowledge 17 Assumptions 17 Nomenclatural conventions 17 PRELIMINARY 18 Concepts and definitions 18 Island nomenclature 18 Scope 20 INSULAR FEATURES AND THE ISLAND SYNDROME 20 Physical description 20 Biological description 23 Reduced species richness 23 Occurrence of endemic species or subspecies 23 Occurrence of unique ecosystems 27 Species characteristic of WA islands 27 Hyperabundance 30 Habitat changes 31 Behavioural changes 32 Morphological changes 33 Changes in niches 35 Genetic changes 35 CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK 36 Degree of exposure to wave action and salt spray 36 Normal exposure 36 Extreme exposure and tidal surge 40 Substrate 41 Topographic variation 42 Maximum elevation 43 Climate 44 Number and extent of vegetation and other types of habitat present 45 Degree of isolation from the nearest source area 49 History: Time since separation (or formation) 52 Planar area 54 Presence of breeding seals, seabirds, and turtles 59 Presence of Indigenous people 60 Activities of Europeans 63 Sampling completeness and comparability 81 Ecological interactions 83 Coups de foudres 94 LINKAGES BETWEEN THE 15 FACTORS 94 ii THE TRANSITION FROM MAINLAND TO ISLAND: KNOWNS; KNOWN UNKNOWNS; AND UNKNOWN UNKNOWNS 96 SPECIES TURNOVER 99 Landbird species 100 Seabird species 108 Waterbird -

080058-89.02.017.Pdf

t9l .Ig6I pup spu?Fr rr"rl?r1mv qnos raq1oaqt dq panqs tou pus 916I uao^\teq sluauennboJ puu surelqord lusue8suuur 1eneds wq sauo8a uc .fu1mpw snorru,r aql uI luar&(oldua ',uq .(tg6l a;oJareqt puuls1oore8ueltr 0t dpo 1u reted lS sr ur saiuzqc aql s,roqs osIB elqeJ srqt usrmoJ 'urpilsny 'V'S) puels tseSrul geu oq; ur 1sa?re1p4ql aql 3o luetugedeq Z alq?J rrr rtr\oqs su padoldua puu prr"lsr aroqsJJorrprJpnsnv qlnos lsJErel aql ruJ ere,u eldoed ZS9 I feqf pa roqs snsseC srllsll?ls dq r ?olp sp qlr^\ puplsl oorp8ue1 Jo neomg u"rl?Jlsnv eql uo{ sorn8g luereJ lsour ,u1 0g€ t Jo eW T86I ul puu 00S € ,{lel?urxorddu sr uoqelndod '(derd ur '8ur,no:8 7r luosaJd eqJ petec pue uoqcnpord ,a uosurqoU) uoqecrJqndro3 peredard Smeq ,{11uermc '(tg6l )potsa^q roJ perualo Suraq puel$ oql Jo qJnu eru sda,r-rnsaseql3o EFSer pa[elop aqJ &usJ qlvrr pedolaaap fuouoce Surqsg puu Surure; e puu pue uosurqo;) pegoder useq aleq pesn spoporu palles-er su,rr prrqsr eql sreo,{ Eurpeet:ns eq1 re,ro prru s{nser druuruqord aqt pue (puep1 ooreSuqtr rnq 698I uI peuopwqs sE^\ elrs lrrrod seaeell eql SumnJcxa) sprrelsl aroqsJJo u"{e4snv qlnos '998I raqueJeo IIl eprelepv Jo tuaruslDesIeuroJ oqt aql Jo lsou uo palelduor ueeq A\ou aaeq s,{e,rrns aro3aq ,(ueduo3 rr"4u4snv qtnos qtgf 'oAE eqt dq ,{nt p:6o1org sree,{009 6 ol 000 L uea r1aq palulosr ur slors8rry1 u,no1paserd 6rll J?eu salaed 'o?e ;o lrrrod ererrirspuulsr Surura sr 3ql Jo dllJolpu aq; sree,{ paqslqplse peuuurad lE s?a\lueurep1os uuedorng y 009 0I spuplsl dpearg pue uosr"ed pup o8e srea,{ 'seruolocuorJ-"3s rel?l puB -

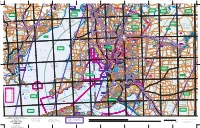

S P E N C E R G U L F S T G U L F V I N C E N T Adelaide

Yatala Harbour Paratoo Hill Turkey 1640 Sunset Hill Pekina Hill Mt Grainger Nackara Hill 1296 Katunga Booleroo "Avonlea" 2297 Depot Hill Creek 2133 Wilcherry Hill 975 Roopena 1844 Grampus Hill Anabama East Hut 1001 Dawson 1182 660 Mt Remarkable SOUTH Mount 2169 440 660 (salt) Mt Robert Grainger Scobie Hill "Mazar" vermin 3160 2264 "Manunda" Wirrigenda Hill Weednanna Hill Mt Whyalla Melrose Black Rock Goldfield 827 "Buckleboo" 893 729 Mambray Creek 2133 "Wyoming" salt (2658±) RANGE Pekina Wheal Bassett Mine 1001 765 Station Hill Creek Manunda 1073 proof 1477 Cooyerdoo Hill Maurice Hill 2566 Morowie Hill Nackara (abandoned) "Bulyninnie" "Oak Park" "Kimberley" "Wilcherry" LAKE "Budgeree" fence GILLES Booleroo Oratan Rock 417 Yeltanna Hill Centre Oodla "Hill Grange" Plain 1431 "Gilles Downs" Wirra Hillgrange 1073 B pipeline "Wattle Grove" O Tcharkuldu Hill T Fullerville "Tiverton 942 E HWY Outstation" N Backy Pt "Old Manunda" 276 E pumping station L substation Tregalana Baroota Yatina L Fitzgerald Bay A Middleback Murray Town 2097 water Ucolta "Pitcairn" E Buckleboo 1306 G 315 water AN Wild Dog Hill salt Tarcowie R Iron Peak "Terrananya" Cunyarie Moseley Nobs "Middleback" 1900 works (1900±) 1234 "Lilydale" H False Bay substation Yaninee I Stoney Hill O L PETERBOROUGH "Blue Hills" LC L HWY Point Lowly PEKINA A 378 S Iron Prince Mine Black Pt Lancelot RANGE (2294±) 1228 PU 499 Corrobinnie Hill 965 Iron Baron "Oakvale" Wudinna Hill 689 Cortlinye "Kimboo" Iron Baron Waite Hill "Loch Lilly" 857 "Pualco" pipeline Mt Nadjuri 499 Pinbong 1244 Iron -

Musgrave Subregional Description

Musgrave Subregional Description Landscape Plan for Eyre Peninsula - Appendix D The Musgrave subregion extends from Mount Camel Beach in the north inland to the Tod Highway, and then south to Lock and then west across to Lake Hamilton in the south. It includes the Southern Ocean including the Investigator Group, Flinders Island and Pearson Isles. QUICK STATS Population: Approximately 1,050 Major towns (population): Elliston (300), Lock (340) Traditional Owners: Nauo and Wirangu nations Local Governments: District Council of Elliston, District Council of Lower Eyre Peninsula and Wudinna District Council Land Area: Approximately 5,600 square kilometres Main land uses (% of land area): Grazing (30% of total land area), conservation (20% of land area), cropping (18% of land area) Main industries: Agriculture, health care, education Annual Rainfall: 380 - 430mm Highest Elevation: Mount Wedge (249 metres AHD) Coastline length: 130 kilometres (excludes islands) Number of Islands: 12 2 Musgrave Subregional Description Musgrave What’s valued in Musgrave Pearson Island is a spectacular The landscapes and natural resources of the Musgrave unspoilt island with abundant and subregion are integral to the community’s livelihoods and curious wildlife. lifestyles. The Musgrave subregion values landscapes include large The coast is enjoyed by locals and visitors for its beautiful patches of remnant bush and big farms. Native vegetation landscapes, open space and clean environment. Many is valued by many in the farming community and many local residents particularly value the solitude, remoteness recognise its contribution to ecosystem services, and and scenic beauty of places including Sheringa Beach, that it provides habitat for birds and reptiles. -

Maintaining the Monitoring of Pup Production at Key Australian Sea Lion Colonies in South Australia (2013/14)

Maintaining the monitoring of pup production at key Australian sea lion colonies in South Australia (2013/14) Simon D Goldsworthy, Alice I Mackay, Peter D Shaughnessy, Fred Bailleul and Clive R McMahon SARDI Publication No. F2010/000665-4 SARDI Research Report Series No. 818 SARDI Aquatics Sciences PO Box 120 Henley Beach SA 5022 December 2014 Final report to the Australian Marine Mammal Centre Goldsworthy, S.D. et al. Australian sea lion population monitoring Maintaining the monitoring of pup production at key Australian sea lion colonies in South Australia (2013/14) Final report to the Australian Marine Mammal Centre Simon D Goldsworthy, Alice I Mackay, Peter D Shaughnessy, Fred Bailleul and Clive R McMahon SARDI Publication No. F2010/000665-4 SARDI Research Report Series No. 818 December 2014 II Goldsworthy, S.D. et al. Australian sea lion population monitoring This publication may be cited as: Goldsworthy, S.D.1, Mackay, A.I.1, Shaughnessy, P.D. 1, 2, Bailleul, F1 and McMahon, C.R.3 (2014). Maintaining the monitoring of pup production at key Australian sea lion colonies in South Australia (2013/14). Final Report to the Australian Marine Mammal Centre. South Australian Research and Development Institute (Aquatic Sciences), Adelaide. SARDI Publication No. F2010/000665-4. SARDI Research Report Series No. 818. 66pp. Cover Photo: Alice I. Mackay 1 SARDI Aquatic Sciences, PO Box 120, Henley Beach, SA 5022 2South Australian Museum, North Terrace, Adelaide, SA, 5000 3 Sydney Institute of Marine Science, 19 Chowder Bay Road, Mosman NSW, 2088 South Australian Research and Development Institute SARDI Aquatic Sciences 2 Hamra Avenue West Beach SA 5024 Telephone: (08) 8207 5400 Facsimile: (08) 8207 5406 http://www.sardi.sa.gov.au DISCLAIMER The authors warrant that they have taken all reasonable care in producing this report. -

South Australian Ornithologist

- THE: South Australian Ornithologist. VOL. XIV.] AFIUL 1, 1938. [Part 6. Notes on some Birds seen on Flinders and other islands off the Eyre Peninsula coasts, February March, 1937. By H. H. Finlayson. The birds noted below wereseen during 11 stay of some three weeks in February of the year 1937 on Flinders. Island and during shorter visits to some other islands of neighbouring coasts and waters. The observations are of a random and desultory kind, being made incidentally to enquiry into the mammal fauna of the places named, and do not relate to more than a small part of the total avifauna, nor include even all the prominent forms. With the exception of Prof. J. B. Cleland's paper on the birds of Pearson's Island (Trans. Roy. Soc. S.A., Vol. XLVII, 119/ 126, 1923), little seems to have been published on the birds of the smaller islands of the South Australian coasts, and even such fragmentary records as the following, provided they are made at first hand, may have value as contributions to the completed lists of the future. Flinders Island has an. area of about 9,000 acres, and lies about 18 miles west of Elliston on the Eyre Peninsula mainland. It has the structure, usual hereabouts, of a limestone platform resting on granite base, which is exposed at the waterline. The coastline is varied and is occupied by cliffs, boulder-shingle, and sand beach in about equal proportion. The soil is in general a shallow light sandy .loam, although firmer red soils occur on the south-west side. -

Eyre Peninsula OCEAN 7

Mount F G To Coober Pedy (See Flinders H I Olympic Dam J Christie Ranges and Outback Region) Village Andamooka Wynbring Roxby Downs To Maralinga Lyons Tarcoola WOOMERA PROHIBITED AREA (Restricted Entry) Malbooma 87 Lake Lake Younghusband Ferguson Patricia 1 1 Glendambo Kingoonya Lake Hanson Lake Torrens 'Coondambo' Lake Yellabinna Regional Kultanaby Lake Hart National Park Lake Harris Wirramn na Woomera Reserve Lake Torre Lake Lake Gairdner Pimba Windabout ns Everard National Park Pernatty Lagoon Island Wirrappa See map on opposite Lake page for continuation Lagoon Dog Fence 'Oakden Hill' Gairdner 'Mahanewo' 2 Yumbarra Conservation Stuart 2 Park 'Lake Everard' Lake Finnis 'Kangaroo To Nundroo (See OTC Earth Wells' 'Yalymboo' Lake Dutton map opposite) Station Bookaloo Pureba Conservation 'Moonaree' Lake Highway Penong 57 1 'Kondoolka' Lake MacFarlane Park 16 Acraman 'Yadlamalka' 59 Nunnyah Con. Res Ceduna 'Yudnapinna' Mudlamuckla 'Hiltaba' Jumpuppy Hesso To Hawker (See Bay Hill Flinders and Koolgera Cooria Hill Outback Region) Point Bell 41 Con. Res 87 Murat Smoky Mt. Gairdner 51 Goat Is. Bay 93 33 Unalla Hill 'Low Hill' St. Peter Smoky Bay Horseshoe Evans Is. Gawler Tent Hill Quorn Island 29 27 Barkers Hill 'Cariewerloo' Hill Eyre Wirrulla 67 'Yardea' 'Mount Ive' Nuyts Archipelago Is. Conservation Haslam 'Thurlga' 50 'Nonning' Park Flinders Port Augusta St. Francis Point Brown 76 Paney Hill Red Hill Streaky 46 25 3 Island 75 61 3 Bay Eyre 'Paney' Ranges Highway Army 27 Harris Bluff 'Corunna' Training Cape Bauer 39 28 43 Poochera Lake Area Olive Island 61 Iron Knob 33 45 Gilles Corvisart Highway 'Buckleboo' Streaky Bay Lake Gilles 47 Bay Minnipa Pinkawillinie Conservation Park 1 56 17 31 Point Westall 21 Highway Conservation Buckleboo 21 35 43 Eyre Sceale Bay 17 Park Iron Baron 88 Cape Blanche 43 13 27 23 Wudinna 24 24 Port Germein Searcy Bay Kulliparu Kyancutta 18 Whyalla Point Labatt Port Kenny 22 Con. -

Nswdpigame Fish Tagging Program

NSW DPI GAME FISH TAGGING PROGRAM REPORT 2017-2018 Introduction .......................................................................................................................................... 5 Figure 1. Number of fish recaptured by year, 2017/18. .................................................................................... 5 The Program to date ............................................................................................................................. 6 Species summary of tagging activity for 2017/18 ................................................................................ 7 Black marlin ....................................................................................................................................................... 9 Southern bluefin tuna ..................................................................................................................................... 10 Blue marlin ...................................................................................................................................................... 10 Striped marlin .................................................................................................................................................. 11 Sailfish .............................................................................................................................................................. 11 Yellowfin tuna ................................................................................................................................................. -

Australian Sea Lions Neophoca Cinerea at Colonies in South Australia: Distribution and Abundance, 2004 to 2008

The following supplement accompanies the article Australian sea lions Neophoca cinerea at colonies in South Australia: distribution and abundance, 2004 to 2008 Peter D. Shaughnessy1,*, Simon D. Goldsworthy2, Derek J. Hamer3,5, Brad Page2, Rebecca R. McIntosh4 1South Australian Museum, North Terrace, Adelaide, South Australia 5000, Australia 2South Australian Research and Development Institute, PO Box 120, Henley Beach, South Australia 5022, Australia 3Department of Earth and Environmental Science, University of Adelaide, Adelaide, South Australia 5005, Australia 4Department of Zoology, La Trobe University, Bundoora, Victoria 3068, Australia 5Present address: Australian Antarctic Division, 203 Channel Highway, Kingston, Tasmania 7050, Australia *Email: [email protected] Endangered Species Research 13: 87–98 (2011) Supplement. Information on 26 Neophoca cinerea breeding colonies in South Australia The Australian sea lion Neophoca cinerea is restricted to South Australia and Western Australia. This supplementary material provides information on 26 breeding colonies in South Australia that were visited during this study between 2004 and 2008, with details on pup population estimates from which best estimates are summarized in Table 1 of the main paper. It also summarises data on pup counts available before 2004. Mark-recapture estimates are presented with their 95% confidence limits (CL). Detailed counts of all animals in these colonies have been presented in consultancy reports. Data for the other 13 breeding colonies and 9 haulout sites with occasional pupping (which were not visited in this study) were taken from published literature. In addition, 24 haulout sites of the Australian sea lion visited during the study are listed in Table S1 of this supplementary material, together with their geographical positions and counts of sea lions seen on the dates visited. -

Diet of the Australian Sea Lion (Neophoca Cinerea): an Assessment of Novel DNA-Based and Contemporary Methods to Determine Prey Consumption

Diet of the Australian sea lion (Neophoca cinerea): an assessment of novel DNA-based and contemporary methods to determine prey consumption Kristian John Peters BSc (hons), LaTrobe University, Victoria Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Adelaide (October, 2016) 2 DECLARATION OF ORIGINALITY I certify that this work contains no material which has been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma in my name, in any university or other tertiary institution and, to the best of my knowledge and belief, contains no material previously published or written by another person, except where due reference has been made in the text. In addition, I certify that no part of this work will, in the future, be used in a submission in my name, for any other degree or diploma in any university or other tertiary institution without the prior approval of the University of Adelaide and where applicable, any partner institution responsible for the joint-award of this degree. I give consent to this copy of my thesis when deposited in the University Library, being made available for loan and photocopying, subject to the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968. I acknowledge that copyright of published works contained within this thesis resides with the copyright holder(s) of those works. I also give permission for the digital version of my thesis to be made available on the web, via the University’s digital research repository, the Library Search and also through web search engines, unless permission has been granted by the University to restrict access for a period of time. -

HYDROGRAPHIC DEPARTMENT Charts, 1769-1824 Reel M406

AUSTRALIAN JOINT COPYING PROJECT HYDROGRAPHIC DEPARTMENT Charts, 1769-1824 Reel M406 Hydrographic Department Ministry of Defence Taunton, Somerset TA1 2DN National Library of Australia State Library of New South Wales Copied: 1987 1 HISTORICAL NOTE The Hydrographical Office of the Admiralty was created by an Order-in-Council of 12 August 1795 which stated that it would be responsible for ‘the care of such charts, as are now in the office, or may hereafter be deposited’ and for ‘collecting and compiling all information requisite for improving Navigation, for the guidance of the commanders of His Majesty’s ships’. Alexander Dalrymple, who had been Hydrographer to the East India Company since 1799, was appointed the first Hydrographer. In 1797 the Hydrographer’s staff comprised an assistant, a draughtsman, three engravers and a printer. It remained a small office for much of the nineteenth century. Nevertheless, under Captain Thomas Hurd, who succeeded Dalrymple as Hydrographer in 1808, a regular series of marine charts were produced and in 1814 the first surveying vessels were commissioned. The first Catalogue of Admiralty Charts appeared in 1825. In 1817 the Australian-born navigator Phillip Parker King was supplied with instruments by the Hydrographic Department which he used on his surveying voyages on the Mermaid and the Bathurst. Archives of the Hydrographic Department The Australian Joint Copying Project microfilmed a considerable quantity of the written records of the Hydrographic Department. They include letters, reports, sailing directions, remark books, extracts from logs, minute books and survey data books, mostly dating from 1779 to 1918. They can be found on reels M2318-37 and M2436-67.