Stylistic Analysis & Close Reading

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2021 Basketball 1-48 Pages.Pub

HISTORY OF BOYS' ALL-STAR GAMES 1955 1959 SOUTH 86, NORTH 82 SOUTH 88, NORTH 74 The South Rebels led by Forest Hill's Freddy As in '57, the North came in outmanned--but Hutton upset the heavily favored North Yankees even more so--to absorb the worst licking yet. to begin an All-Star tradition. Hutton hit 13 Joe Watson of Pelahatchie and Robert Parsons field goals for 26 points, mostly from far out, of West Lincoln got 22 and 21 respectively for and had able scoring support up front as Ger- the victors. Moss Point's Jimmy McArthur made ald Martello of Cathedral got 16, Wayne Pulliam it easy for them by nabbing 24 rebounds. Co- of Sand Hill 15 and Jimmy Graves of Laurel 14. lumbus' James Parker, with 16, topped the los- Larry Eubanks of Tupelo led a losing cause with ers. 20 and Jerry Keeton of Wheeler had 16. 1960 1956 NORTH 95, SOUTH 82 SOUTH 96, NORTH 90 After five years of futility, the North finally broke This thriller went into double overtime before its losing jinx, piling up the largest victory mar- the South, after trailing early, pulled out front gin yet in the All-Star series. Complete command to stay. Wayne Newsome of Walnut tallied 27 of the backboards gave the Yanks a 73-50 re- points in vain for the North. Donald Clinton of bounding edge. Balanced North scoring, led by Oak Grove and Gerald Saxton of Forest had 17 Charles Jeter of Ingomar with 25 points and each to top the South, but it was the late scor- Butch Miller of Jackson Central with 22, offset ing burst of Puckett's Mike Ponder that saved an All-Star game record of 32 by the South's the Rebels. -

Shake N' Score Instructions

SHAKE N’ SCORE INSTRUCTIONS Number of Players: 2+ Ages: 6+ Fadeaway Jumper: Score in this row only if the dice show any sequence Contents: 1 Dice Cup, 5 Dice, 1 Scorepad of four numbers. Any Fadeaway Jumper is worth 30 points. For example with the dice combination shown below, a player could score 30 points in the SET UP: Each player takes a scorecard. To decide who goes first, players Fadeaway Jumper row. take turns rolling all 5 dice. The player with the highest total goes first. Play ANY passes to the left. Logo # PLAY: To start, roll all 5 dice. After rolling, a player can either score the Other Scoring Options: Using the same dice, a player could instead score in current roll, or reroll any or all of the dice. A player may only roll the dice the Foul row, or in the appropriate First Half rows. a total of 3 times. After the third roll, a player must choose a category to score. A player may score the dice at any point during their turn. A player Slam Dunk: Score in this row only if the dice show any sequence of five does not have to wait until the third roll. numbers. Any Slam Dunk is worth 40 points. For example, a player could score 40 points in the Slam Dunk box with the dice combination shown below. SCORING: When a player is finished rolling, they must decide which row to fill on their scorecard. For each game, there is 1 column of 13 rows on the scorecard; 6 games can be played per scorecard. -

The Fundamentals of Shooting the Basketball

The Fundamentals of Shooting the Basketball The objective of the offense in Basketball is accuracy of each attempted shot. Most players recognize this; but, only the better shooters learn how to practice correctly and work at improvement year round. Since most of this practice sessions are alone, every player must be his own critic. This means he\she must understand the proper mechanics that affect the success, or failure, of every shot. Every player must know his range and know what is a good shot. Therefore, before examining the techniques associated with the various shots, a good basketball player is expected to have in his arsenal, here are the principles at work in every scoring shot from anywhere on a basketball court. These are divided into two parts, the mental aspect and the physical aspect: 1. Mental. At no time is psychological conditioning more critical than when shooting the basketball in a game. Knowing when to shoot and being able to do it effectively under pressure distinguishes the great shooter from the ordinary. Regardless of how much he practices, or how well he conditions himself, only a modest amount of improvement is possible in speed, reflexes, or strength. History gives many examples of players able to achieve greatness despite mediocre physical talent. Usually, however, such successes are due to determination. a. Concentration: is the fixing of attention on the job at hand and is characteristic of every great athlete. Through continuous practice, good shooters develop their concentration to the extent that they are oblivious to every distraction. Ability to relax: is closely related to concentration. -

2019 NCBBA Skills Rules

850 Ridge Avenue Suite 301 Pittsburgh, PA 15212 Office: (412) 321-8440 Fax: (412) 321-4088 2019 NCBBA Skills Competition Rule Book 3-Point Shooting Competition This will be a timed event in which a stopwatch will be keeping track of the amount of time it takes you to complete the task. Each contestants will be timed as to how quickly they can make 5 3-Point shots, 1 from each of 5 different spots marked by cones (corner, wing, top of key, wing, and corner) All contestants will start in either corner position and the stopwatch will start as soon as the first shot leaves the players hand. The contestants may not move onto the next position until they make the shot in the particular position they are in. Time will stop when the player’s ball travels through the net on the last position. Format 12 shooters will compete in the first round with the top 6 shooters moving onto the next round. 6 shooters will compete in the second round with the top 3 shooters moving onto the final round. 3 shooters will compete in the championship round with the top shooter (champion) being decided by that player achieving the least amount of time to make baskets from all 5 spots. 3-Point Challenge Winner Explanation Shooter Name 1st Round 2nd Round Champ Round 1 2:30 Eliminated Eliminated 2 2:29 Eliminated Eliminated 3 2:28 Eliminated Eliminated 4 2:27 Eliminated Eliminated 5 2:26 Eliminated Eliminated 6 2:25 Eliminated Eliminated 7 2:24 1:58 Eliminated 8 2:23 1:57 2:11 9 2:22 1:56 1:59 10 2:21 1:55 1:48 (winner) 11 2:20 2:45 Eliminated 12 2:19 2:17 Eliminated NCBBA Obstacle Course © 2011 National Club Basketball Association 850 Ridge Avenue Suite 301 Pittsburgh, PA 15212 Office: (412) 321-8440 Fax: (412) 321-4088 Designed course by the NCBBA in order to test the basketball all around skills of a player. -

Analyzing Sometimes It's Helpful to Start by Summarizing the Work in One Sentence, Just So You're Sure What's Going On

2 CHAPTER 2 • CLOSE READING Of joy, & we knew we were Beautiful & dangerous. 40 {1992) Analyzing Sometimes it's helpful to start by summarizing the work in one sentence, just so you're sure what's going on. In "Slam, Dunk, & Hook," the speaker expresses how basketball provided an escape from his life's troubles. Clearly, even this initial statement engages in a certain level of interpretation-not only does it state that the poem is about basketball, but it also draws the inference that the speaker's life was troubled and that basketball was his means of escape. The next step is examining what makes the poem more complex than this brief summary. How does Komunyakaa convey a sense of exuberance? of joy? of danger? How does he make the situation something we feel rather than just read about? Let's begin our analysis by thinking a bit about the poem's title. It's all about action, about moves. But a "slam dunk" is just one move, so why is there a comma between "Slam" and "Dunk"? Does this construction anticipate the rhythm in the poem itself? Our next consideration could be the speaker, who is evidently reflect ing on a time in his youth when he played basketball with his friends. The speaker describes the "metal hoop" that was "Nailed to [their] oak" and a backboard "splin tered" by hard use. We're not in the world of professional sports or even in the school gym. You will probably notice some things about the poem as a whole, such as its short lines, strong verbs, and vivid images. -

Basketball and Philosophy, Edited by Jerry L

BASKE TBALL AND PHILOSOPHY The Philosophy of Popular Culture The books published in the Philosophy of Popular Culture series will il- luminate and explore philosophical themes and ideas that occur in popu- lar culture. The goal of this series is to demonstrate how philosophical inquiry has been reinvigorated by increased scholarly interest in the inter- section of popular culture and philosophy, as well as to explore through philosophical analysis beloved modes of entertainment, such as movies, TV shows, and music. Philosophical concepts will be made accessible to the general reader through examples in popular culture. This series seeks to publish both established and emerging scholars who will engage a major area of popular culture for philosophical interpretation and exam- ine the philosophical underpinnings of its themes. Eschewing ephemeral trends of philosophical and cultural theory, authors will establish and elaborate on connections between traditional philosophical ideas from important thinkers and the ever-expanding world of popular culture. Series Editor Mark T. Conard, Marymount Manhattan College, NY Books in the Series The Philosophy of Stanley Kubrick, edited by Jerold J. Abrams The Philosophy of Martin Scorsese, edited by Mark T. Conard The Philosophy of Neo-Noir, edited by Mark T. Conard Basketball and Philosophy, edited by Jerry L. Walls and Gregory Bassham BASKETBALL AND PHILOSOPHY THINKING OUTSIDE THE PAINT EDITED BY JERRY L. WALLS AND GREGORY BASSHAM WITH A FOREWORD BY DICK VITALE THE UNIVERSITY PRESS OF KENTUCKY Publication -

Lesson No. Subject: Basketball Lesson Description: Hook Shot Year: Group: Ability: Day: Period: Duration: Total No.: M: F: SEN

Lesson no. Subject: Basketball Lesson description: Year: Group: Ability: Day: Period: Duration: Total No.: M: F: 1 Hook shot 10 SEN: Objectives: To be able to confidently perform with accuracy, the Hook shot. To develop knowledge and understanding of the Hook shot, and where and why it is performed in Basketball. To incorporate the hook shot into a small sided game of Basketball Activity Description Objectives Teaching Points Differentiation Assessment and Evaluation of Creativity, Resilience and Tactics Link to Theoretical PE Performance Aspects Warm Up 3 MAN WEAVE To comprehend and grasp the importance of a Pass and Follow ball ↑ Allow dribble Observe pupils performances R✚ Observe a student who has a drive to succeed warm up Do not dribble ↑ Catch re - bound Use warm up cards with key Q). The Skeletal system To confidently perform with accuracy, the 3 man Use lay up to score phrases R✚ Students learn from the positives and negatives has several functions weave correctly correctly identify and Pair Students arranged in a circle. To understand the importance of stretching at Hold stretches for 8 seconds. ↑ Get pupils to incorporate Q & A on benefits of stretching R✚ Students build up a sense of togetherness describe 3. Stretching Teacher leads through series of the start of the session. No bouncing. stretching with Objects used and their warm ups stretches and questions students To know the names of major muscles. To carry out within Basketball Q). Relate the three as to what muscles we were in pairs correct stretching routines safely. -

Fitwall Adds Sports Icon Julius Erving As Advisor for Global Expansion

For Immediate Release Contact: Elizabeth Ireland Stalwart Communications (858) 922-9983 [email protected] Fitwall adds sports icon Julius Erving as advisor for global expansion - NBA Hall of Famer to work with management team, franchisees on fitness and stra- tegic opportunities - IRVINE, Calif. – February 3, 2015 – Fitwall, one of the world’s most innovative fitness companies, announces Hall of Fame American basketball player Julius “Dr. J” Erving has joined Fitwall as a strategic advisor. The announcement follows the launch of Fitwall’s new franchise platform and plans to sign deals for 200 studios in the next 24 months. “There is added pressure on someone like Julius to choose the best possible business opportunities and we’re pleased he is partnering with Fitwall to bring unprecedented change to the fitness industry,” said Michael Webb, Fitwall’s President. “His understand- ing of athletics, the sports business and fitness universe will bring tremendous value as we expand globally.” Fitwall studios offer high-intensity interval training sessions that deliver strength, cardio- vascular fitness and flexibility all in 40 minutes. Members check in on an iPad and click into the Fitwall using a Bluetooth heart rate monitor to receive constant feedback throughout the workout. Fitwall utilizes a propriety metric called the FIT (Fitwall Intensity Training) Factor, a data calculation that helps clients track progress and maximize re- sults. Erving noted, “I exercise regularly on the Fitwall and feel stronger than I have in years. The workout is fun and delivers extraordinary results in a fraction of the time. The global fitness industry is ready for change and I’m excited to help make Fitwall even more ac- cessible to a broad range of consumers; be they young, old, amateur or professional.” Erving helped launch a modern style of basketball play that emphasized leaping and play above the rim. -

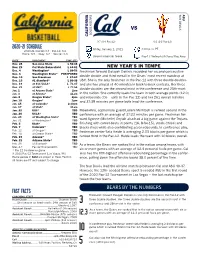

2020-21 Schedule Fast Facts Bears by the Numbers

SUN DEVILS ASU VS GOLDEN BEARS CALIFORNIA 0-7 (0-4 Pac-12) 6-2 (2-2 Pac-12) 2020-21 SCHEDULE Friday, January 1, 2021 2:00 p.m. PT 2020-21 Overall: 0-7• Pac-12: 0-4 Home: 0-5 • Away: 0-2 • Neutral: 0-0 Desert Financial Arena Pac-12 Network/Arizona/Bay Area DATE OPPONENT TIME (PT) Nov. 25 San Jose State L 56-48 Nov. 29 Cal State Bakersfield L 60-52 NEW YEAR’S IN TEMPE Dec. 4 Washington* L 80-53 Freshman forward Dalayah Daniels recorded her second-consecutive Dec. 6 Washington State* POSTPONED Dec. 10 San Francisco L 67-62 double-double and third overall in the Bears’ most recent matchup at Dec. 13 #1 Stanford* L 83-38 USC. She is the only freshman in the Pac-12 with three double-doubles Dec. 19 at #11 UCLA* L 71-37 and she has played all 40 minutes in back-to-back contests. Her three Dec. 21 at USC* L 77-54 Jan. 1 at Arizona State* 2pm double-doubles are the second most in the conference and 25th-most Jan. 3 at Arizona* 11am in the nation. She currently leads the team in both average points (12.0) Jan. 8 Oregon State* 2pm and rebounds (7.6 – sixth in the Pac-12) and her 261 overall minutes Jan. 10 Oregon* 1pm and 37:39 minutes per game both lead the conference. Jan. 15 at Colorado* 2:30pm Jan. 17 at Utah* 11am Jan. 22 USC* TBD Meanwhile, sophomore guard Leilani McIntosh is ranked second in the Jan. -

Shooting Guide – “Home-Court Challenge”

Shooting Guide – “Home-Court Challenge” 1) Pacesetter Decathalon - 10 categories of “game” shots – shoot sets of 100 Choose from the following categories of Pacesetter Decathalon shots. You may shoot 10 shots in each category or shoot 100 in one category or mix categories. But always shoot categories in multiples of 10, like 10-20-30....100. Record total of 100. A) Touch shots – 10 “perfect form shooting” shots 1) 6-foot right side 2) 6-foot middle 3) 6-foot left side 4) 8-foot bank shot right side – just above block out of lane 5) 8-foot bank shot left side - just above block out of lane 6) 12-foot right side shot 7) 12-foot left side shot 8) 15-foot elbow shot right side – highest lane marking 9) 15-foot elbow shot left side – highest lane marking 10) Free throw B) Free throws C) Power shots – 45-degree angle bank shots from 3 feet – alternate sides – right-left-right, etc. Jump off two feet. D) Mikan shots – 45-degree angle hook shots. Start 3 feet in front of basket facing sideline. Take one angled step between block and basket and swing “arm-extended” hook shot off backboard. Alternate sides – right-left-right-etc. E) Jump hooks – stand 3 feet from the basket facing the baseline between the block and the basket. Jump off both feet and shoot hook shot from standing position – no step. Jump straight up, arm to ear, and flip ball off backboard. F) Bank shots – First shot 3 feet away at 45-degree angle, step back to 6 feet for 2nd shot, then 9 feet, 12 feet and 15 feet. -

Guide to the Arthur Ehrat Papers

Guide to the Arthur Ehrat Papers NMAH.AC.0907 Tamara Salman. 2006 August Archives Center, National Museum of American History P.O. Box 37012 Suite 1100, MRC 601 Washington, D.C. 20013-7012 [email protected] http://americanhistory.si.edu/archives Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Arrangement................................................................................................................... 10 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 4 Biographical / Historical.................................................................................................... 2 Names and Subjects .................................................................................................... 12 Container Listing ........................................................................................................... 13 Series 1 : Background Materials, 1968-2005......................................................... 13 Series 2 : Patent Records for Basketball Rim, 1865-1984 (bulk 1970s-1984)........ 16 Series 3 : Civil Action and Settlement Records, 1984-1996.................................. 17 Series 4 : Licensing Agreements, 1980 - 2000...................................................... 20 Series 5: Field Spreader -

EFFECTIVE OFFENSIVE POST PLAY INVOLVES “CREATING SPACE” It

EFFECTIVE OFFENSIVE POST PLAY INVOLVES “CREATING SPACE” It is a misconception, when shooting in the low post area, the player should shoot over the opponent. That works well if you’re seven feet tall, but what about those who are at the short end of the height mismatch? How do they get an open shot? LOCATION FOR INITIATING MOVES The answer lies in “creating space” from the defender. We’re going to assume the taller defender is not going to front his opponent and the ball can be caught at the mid post. The mid post is the most effective starting place for post moves. Too low and there is no baseline option. If a player is straddling a point any lower than the first line above the block, he is too low. Pivoting baseline to face the basket from the mid post provides a perfect angle for the bank shot: the forty-five degree angle. The mid post location is also good for stepping into the key for the hook shot, or making a drive toward the hoop. CREATING SPACE No offensive arsenal, from any location on the floor, is effective without the threat of penetration. Even the greatest offensive player in history, Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, was a constant threat to wheel around a defender for the short hook shot. This threat caused defenders to give him space by backing off. Any player who played Kareem tight, would immediately find Kareem closer to the basket than he was. The threat of the drive creates space. Therefore, we must teach our post, when posting up with the defender behind, to read the defense and make baseline drop step, baseline spin move, or hook shot across the key if possible.