1 Lance Corporal Joseph Ezekiel

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rancourt-Bouchavesnes-Bergen

Association « Paysages et Sites de mémoire de la Grande Guerre » SECTEUR L - Rancourt-Bouchavesnes-Bergen Description générale du secteur mémoriel Le secteur mémoriel de Rancourt s’inscrit sur le plateau du Vermandois, au nord-est de la vallée de la Somme. Constitué d’un socle de craie, il est recouvert d’une épaisse couche de limon et est ciselé de quelques vallées sèches. Le secteur mémoriel se situe en hauteur, en marge du village de Rancourt, au sud et au sud-ouest de la commune. Il domine Bouchavesnes-Bergen au nord et s'étend sur le territoire communal des deux villages. Il s'intègre dans un environnement rural et agraire d’openfield préservé, garantissant une bonne co-visibilité entre chaque site et soulignant leur alignement. Si le cimetière allemand et la nécropole française sont dotés de grands arbres, quelques bois ponctuent l’espace au-delà du périmètre de la zone tampon proposée. Le secteur mémoriel présente une triple symbolique : - c'est le lieu qui incarne la participation française à la bataille de la Somme. La situation topographique du site SE 06 a contribué à en faire une position de défense naturelle des Allemands pendant la bataille de la Somme en 1916, que les Français ont conquise en subissant au minimum 190 000 pertes (morts, blessés et disparus) sur les quatre mois et demi que dure la bataille. La nécropole nationale française et la Chapelle du Souvenir Français ont contribué, dès leur édification, à faire perdurer la mémoire du lieu, des hommes qui y ont participé et des événements qui s'y sont tenus ; - la proximité géographique et la co-visibilité entre les sites attachés à chacune des trois grandes nations combattantes (Allemagne, France et Royaume-Uni) en font un paysage funéraire fort et international. -

Procès Verbal Du Conseil Communautaire Du

PROCES-VERBAL DE LA REUNION DU CONSEIL COMMUNAUTAIRE Jeudi 20 Juin 2018 L’an deux mille dix-huit, le jeudi vingt juin, à dix-huit heures, le Conseil Communautaire, légalement convoqué, s’est réuni au nombre prescrit par la Loi, à PERONNE, en séance publique. Etaient présents : Aizecourt le Bas : Mme Florence CHOQUET - Aizecourt le Haut : M. Jean-Marie DELEAU - Allaines : M. Etienne DEFFONTAINES - Barleux : M. Éric FRANÇOIS - Bernes : M. Yves PREVOT- Bouvincourt en Vermandois : M. Fabrice TRICOTET – Brie : M. Claude JEAN - Buire Courcelles : M. Benoît BLONDE - Bussu : M. Géry COMPERE - Cléry-sur-somme : M. Dominique LENGLET - Doingt-Flamicourt : M. Michel LAMUR, M. Frédéric HEMMERLING - Epehy : M. Paul CARON, M. Jean Michel MARTIN - Equancourt : M. Christophe DECOMBLE - Estrées Mons : Mme Corinne GRU - Etricourt Manancourt : Mme Jocelyne PRUVOST - Fins : M. Daniel DECODTS - Flers : M. Pierrick CAPELLE – Ginchy : M. Dominique CAMUS – Gueudecourt : M.DELATTRE Daniel - Guillemont – M. Didier SAMAIN - Guyencourt- Saulcourt : M. Jean-Marie BLONDELLE - Hancourt : M. Philippe WAREE - Hardecourt aux Bois : M. Bernard FRANÇOIS - Hem Monacu : M. Bernard DELEFORTRIE - Herbécourt : M. Jacques VANOYE - Hervilly Montigny : M. Gaëtan DODRE - Heudicourt : M. Serge DENGLEHEM - Le Ronssoy : M. Jean François DUCATTEAU - Lesboeufs : M. Etienne DUBRUQUE - Liéramont : Mme Véronique JUR - Longueval : M. Jany FOURNIER - Marquaix Hamelet : M. Bernard HAPPE - Maurepas Leforest : M. Bruno FOSSE - Mesnil Bruntel : M. Jean-Dominique PAYEN - Mesnil en Arrouaise : M. Alain BELLIER - Moislains : M. Guy BARON, M. Jean-Pierre CARPENTIER - Nurlu : M. Pascal DOUAY - Péronne : M. Houssni BAHRI, Mme DHEYGHERS Thérèse(quitté la séance à 20h39), Mme Christiane DOSSU, Mme Anne-Marie HARLE, M. Olivier HENNEBOIS, M. Arnold LAIDAN, M. Jean-Claude SELLIER, M. -

Tanks at the Battle of Flers-Courcelette, September 1916

“A useful accessory to the infantry, but nothing more” Tanks at the Battle of Flers-Courcelette, September 1916 Andrew McEwen he Battle of Flers-Courcelette Fuller was similarly unkind about the Tstands out in the broader memory Abstract: The Battle of Flers- tanks’ initial performance. In his Tanks of the First World War due to one Courcelette is chiefly remembered in the Great War, Fuller wrote that the as the combat introduction of principal factor: the debut of the tanks. The prevailing historiography 15 September attack was “from the tank. The battle commenced on 15 maligns their performance as a point of view of tank operations, not September 1916 as a renewed attempt lacklustre debut of a weapon which a great success.”3 He, too, argued that by the general officer commanding held so much promise for offensive the silver lining in the tanks’ poor (GOC) the British Expeditionary warfare. However, unit war diaries showing at Flers-Courcelette was that and individual accounts of the battle Force (BEF) General Douglas Haig suggest that the tank assaults of 15 the battle served as a field test to hone to break through German lines on September 1916 were far from total tank tactics and design for future the Somme front. Flers-Courcelette failures. This paper thus re-examines deployment.4 One of the harshest shares many familiar attributes the role of tanks in the battle from verdicts on the tanks’ debut comes with other Great War engagements: the perspective of Canadian, British from the Canadian official history. and New Zealand infantry. It finds troops advancing across a shell- that, rather than disappointing Allied It commented that “on the whole… blasted landscape towards thick combatants, the tanks largely lived the armour in its initial action failed German defensive lines to capture up to their intended role of infantry to carry out the tasks assigned to it.” a few square kilometres of barren support. -

The Beaumont Hamel Newfoundland Memorial on the Somme, Cultural Geographies, 11, Pp.235-258

[email protected] Gough, P.J. (2004) Sites in the imagination: the Beaumont Hamel Newfoundland Memorial on the Somme, Cultural Geographies, 11, pp.235-258 Sites in the imagination: the Beaumont Hamel Newfoundland Memorial on the Somme. Professor Paul Gough University of the West of England, Bristol Frenchay Bristol BS16 [email protected] ABSTRACT The Beaumont Hamel Newfoundland Memorial is a 16.5 hectare (40 acres) tract of preserved battleground dedicated to the memory of the 1st Newfoundland Regiment who suffered an extremely high percentage of casualties during the first day of the Battle of the Somme in July 1916. Beaumont Hamel Memorial is an extremely complex landscape 1 [email protected] of commemoration where Newfoundland, Canadian, Scottish and British imperial associations compete for prominence. It is argued in the paper that those who chose the site of the Park, and subsequently re-ordered its topography, helped to contrive a particular historical narrative that prioritised certain memories over others. In its design, the park has been arranged to indicate the causal relationship between distant military command and immediate front-line response, and its topographical layout focuses exclusively on a thirty-minute military action during a fifty-month war. In its preserved state the part played by the Royal Newfoundland Regiment can be measured, walked and vicariously experienced. Such an achievement has required close semiotic control and territorial demarcation in order to render the „invisible past‟ visible, and to convert an emptied landscape into significant reconstructed space. This paper examines the initial preparation of the site in the 1920s and more recent periods of conservation and reconstruction. -

Newfoundland's Cultural Memory of the Attack at Beaumont Hamel

Glorious Tragedy: Newfoundland’s Cultural Memory of the Attack at Beaumont Hamel, 1916-1925 ROBERT J. HARDING THE FIRST OF JULY is a day of dual significance for Newfoundlanders. As Canada Day, it is a celebration of the dominion’s birth and development since 1867. In Newfoundland and Labrador, the day is also commemorated as the anniversary of the Newfoundland Regiment’s costliest engagement during World War I. For those who observe it, Memorial Day is a sombre occasion which recalls this war as a trag- edy for Newfoundland, symbolized by the Regiment’s slaughter at Beaumont Hamel, France, on 1 July 1916. The attack at Beaumont Hamel was depicted differently in the years immedi- ately following the war. Newfoundland was then a dominion, Canada was an impe- rial sister, and politicians, clergymen, and newspaper editors offered Newfoundlanders a cultural memory of the conflict that was built upon a trium- phant image of Beaumont Hamel. Newfoundland’s war myth exhibited selectively romantic tendencies similar to those first noted by Paul Fussell in The Great War and Modern Memory.1 Jonathan Vance has since observed that Canadians also de- veloped a cultural memory which “gave short shrift to the failures and disappoint- ments of the war.”2 Numerous scholars have identified cultural memory as a dynamic social mechanism used by a society to remember an experience common to all its members, and to aid that society in defining and justifying itself.3 Beau- mont Hamel served as such a mechanism between 1916 and 1925. By constructing a triumphant memory based upon selectivity, optimism, and conjured romanticism, local mythmakers hoped to offer grieving and bereaved Newfoundlanders an in- spiring and noble message which rationalized their losses. -

1066010 Private Orlando Brown (Regimental Number 2670)

Private Orlando Brown (Regimental Number 2670), having no known last resting-place, is commemorated beneath the Caribou in Beaumont-Hamel Memorial Park. His occupation prior to military service recorded as that of a fisherman earning an annual $400.00, Orlando Brown was a recruit of the Ninth Draft. Having presented himself for medical examination at the Church Lads Brigade Armoury in St. John’s on April 28, 1916, he then enlisted for the duration of the war – engaged at the daily private soldier’s rate of $1.10 – a single day later, on April 29, before attesting three days later again, on May 2. Private Brown sailed from St. John’s on July 19 on board His Majesty’s Transport Sicilian* (right). The ship - refitted some ten years previously to carry well over one thousand passengers - had left the Canadian port of Montreal on July 16, carrying Canadian military personnel. It is likely that the troops disembarked in the English west- coast port-city of Liverpool; however, it is certain that upon disembarkation the contingent journeyed north by train to Scotland and to the Regimental Depot. *Some sixteen years previously - as of 1899 when she was launched – the vessel had served as a troop-ship and transport during another conflict, carrying men, animals and equipment to South Africa for use during the Second Boer War. The Regimental Depot had been established during the summer of 1915 in the Royal Borough of Ayr on the west coast of Scotland, there to serve as the base for the 2nd (Reserve) Battalion. It was from there – as of November of 1915 and up until January of 1918 – that the new-comers arriving from home were despatched in drafts, at first to Gallipoli and later to the Western Front, to bolster the four st fighting companies of 1 Battalion. -

Canadian Cavalry on the Western Front, 1914-1918

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 4-9-2013 12:00 AM "Smile and Carry On:" Canadian Cavalry on the Western Front, 1914-1918 Stephanie E. Potter The University of Western Ontario Supervisor Dr. B. Millman The University of Western Ontario Graduate Program in History A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree in Doctor of Philosophy © Stephanie E. Potter 2013 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the Military History Commons Recommended Citation Potter, Stephanie E., ""Smile and Carry On:" Canadian Cavalry on the Western Front, 1914-1918" (2013). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 1226. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/1226 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “SMILE AND CARRY ON:” CANADIAN CAVALRY ON THE WESTERN FRONT, 1914-1918 by Stephanie Elizabeth Potter Graduate Program in History A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The School of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies The University of Western Ontario London, Ontario, Canada Stephanie Elizabeth Potter 2013 Abstract Although the First World War has been characterized as a formative event in Canadian History, little attention has been paid to a neglected and often forgotten arm of the Canadian Expeditionary Force, the Cavalry. The vast majority of Great War historians have ignored the presence of mounted troops on the Western Front, or have written off the entire cavalry arm with a single word – ‘obsolete.’ However, the Canadian Cavalry Brigade and the Canadian Light Horse remained on the Western Front throughout the Great War because cavalry still had a role to play in modern warfare. -

Beaumont-Hamel and the Battle of the Somme, Onwas Them, Trained a Few and Most Were Minutes Within Killed of the Assault

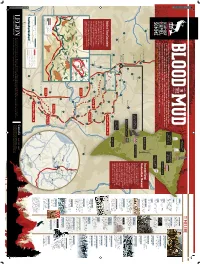

2015-12-18 2:03 PM Hunter’s CWGC TIMELINE Cemetery 1500s June 1916 English fishermen establish The regiment trains seasonal camps in Newfoundland in the rain and mud, waiting for the start of the Battle of the Somme 1610 The Newfoundland Company June 28, 1916 Hawthorn 51st (Highland) starts a proprietary colony at Cuper’s Cove near St. John’s The regiment is ordered A century ago, the Newfoundland Regiment suffered staggering losses at Beaumont-Hamel in France Ridge No. 2 Division under a mercantile charter to move to a forward CWGC Cemetery Monument granted by Queen Elizabeth I trench position, but later at the start of the Battle of the Somme on July 1, 1916. At the moment of their attack, the Newfoundlanders that day the order is postponed July 23-Aug. 7, 1916 were silhouetted on the horizon and the Germans could see them coming. Every German gun in the area 1795 Battle of Pozières Ridge was trained on them, and most were killed within a few minutes of the assault. German front line Newfoundland’s first military regiment is founded 9:15 p.m., June 30 September 1916 For more on the Newfoundland Regiment, Beaumont-Hamel and the Battle of the Somme, to 2 a.m., July 1, 1916 Canadian troops, moved from go to www.legionmagazine.com/BloodInTheMud. 1854 positions near Ypres, begin Newfoundland becomes a crown The regiment marches 12 kilo- arriving at the Somme battlefield Y Ravine CWGC colony of the British Empire metres to its designated trench, Cemetery dubbed St. John’s Road Sept. -

Claremen Who Fought in the Battle of the Somme July-November 1916

ClaremenClaremen who who Fought Fought in The in Battle The of the Somme Battle of the Somme July-November 1916 By Ger Browne July-November 1916 1 Claremen who fought at The Somme in 1916 The Battle of the Somme started on July 1st 1916 and lasted until November 18th 1916. For many people, it was the battle that symbolised the horrors of warfare in World War One. The Battle Of the Somme was a series of 13 battles in 3 phases that raged from July to November. Claremen fought in all 13 Battles. Claremen fought in 28 of the 51 British and Commonwealth Divisions, and one of the French Divisions that fought at the Somme. The Irish Regiments that Claremen fought in at the Somme were The Royal Munster Fusiliers, The Royal Irish Regiment, The Royal Irish Fusiliers, The Royal Irish Rifles, The Connaught Rangers, The Leinster Regiment, The Royal Dublin Fusiliers and The Irish Guards. Claremen also fought at the Somme with the Australian Infantry, The New Zealand Infantry, The South African Infantry, The Grenadier Guards, The King’s (Liverpool Regiment), The Machine Gun Corps, The Royal Artillery, The Royal Army Medical Corps, The Royal Engineers, The Lancashire Fusiliers, The Bedfordshire Regiment, The London Regiment, The Manchester Regiment, The Cameronians, The Norfolk Regiment, The Gloucestershire Regiment, The Westminister Rifles Officer Training Corps, The South Lancashire Regiment, The Duke of Wellington's (West Riding Regiment). At least 77 Claremen were killed in action or died from wounds at the Somme in 1916. Hundred’s of Claremen fought in the Battle. -

Ernest James Thelwell

166: Ernest James Thelwell Basic Information [as recorded on local memorial or by CWGC] Name as recorded on local memorial or by CWGC: Ernest James Thelwell Rank: Private Battalion / Regiment: King’s Coy. 1st Battalion Grenadier Guards Service Number: 23178 Date of Death: 25 September 1916 Age at Death: 25 Buried / Commemorated at: Thiepval Memorial, Thiepval, Departement de la Somme, Picardie, France Additional information given by CWGC: Son of James and Catherine Thelwell, of 38, Overleigh Rd., Chester. Ernest James Thelwell was the eldest son of Police Constable James and Catherine Thelwell and he was born on 22 March 1892 when his parents were living in Eastham. James Thelwell (a son of agricultural labourer William and Sarah Thelwell) married Catherine Jones (a daughter of Thomas) at St Mary’s Church, Edge Hill, Liverpool in late 1889 and their first child, Dora Elizabeth, was born in late 1890 when James was a constable in Woodchurch. In the 1891 census the family was still recorded in Woodchurch: 1901 census (extract) – Upton Road, Woodchurch, Birkenhead James Thelwell 27 police constable born Malpas Catherine 27 born Denbigh Dora 6 months born Woodchurch By the time of the 1901 census the family had moved to Neston where James was a policeman. It appears that James left the police force in Birkenhead to join the constabulary in Eastham shortly after the 1891 census and he remained there until (probably) mid-1897. 1901 census (extract) – Parkgate Road, Neston James Thelwell 38 police constable born Malpas Catherine 38 born Denbigh Dora 10 born Chester Ernest 9 born Eastham William 7 born Eastham Ruth 6 born Eastham Gwenyth 5 born Eastham Charles 3 born Neston Henry 2 months born Neston Page | 1745 Although the census records that Dora Elizabeth was born in Chester it is known that she was born in Woodchurch. -

FAIT LE BEAU TEMPS EN HAUTE SOMME ! Elaboration Du Plan Local D’Urbanisme Intercommunal Aujourd’Hui Nous Bâtissons Demain

PLUiPlan Local d'Urbanisme intercommunal LE PLUi FAIT LE BEAU TEMPS EN HAUTE SOMME ! Elaboration du Plan Local d’Urbanisme intercommunal Aujourd’hui nous bâtissons demain. Soyons les premiers artisans de notre avenir ! Chers Habitants, «C’est un projet En 2016, le Conseil Communautaire, représentant les 60 communes ambitieux, volontariste de votre Communauté de Communes de la Haute Somme, a décidé de et courageux.» se lancer dans la démarche d’élaboration d’un Plan Local d’Urbanisme Intercommunal. Plus que de répondre à une demande de la loi ALUR (Accès au Logement et un Urbanisme Rénové) de 2014, plus que d’écrire des documents d’urbanisme nécessaires à toute collectivité, la volonté du Conseil Communautaire est de tracer les grandes lignes du développement de notre urbanisme local, de notre développement économique pour les prochaines années. En fait, autant que faire se peut, dans les limites imposées par le législateur et des contraintes géographiques, économiques, environnementales, il s’agit d’être les acteurs de notre destin. C’est un projet ambitieux, volontariste et courageux. C’est le projet de vos élus et c’est également le vôtre. C’est pourquoi, je vous invite à en prendre connaissance dans ce Éric FRANÇOIS document, qui conclut la première étape de notre démarche : le Président de la CCHS diagnostic. Maire de Barleux Pour toutes vos demandes d’information, de précisions, vos élus et les services de la Communauté de Communes de la Haute Somme sont à votre disposition. Vous trouverez également de nombreuses informations sur le site internet dédié : http://plui.coeurhautesomme.fr/ Bonne lecture Pourquoi élaborer un PLUi ? Un projet commun d’aména- cuments d’urbanisme commu- Statut d'avancement des documents gement et de développement naux. -

ELECTIONS MUNICIPALES 1Er Tour Du 15 Mars 2020

ELECTIONS MUNICIPALES 1er tour du 15 Mars 2020 Livre des candidats par commune (scrutin plurinominal) Page 1 Elections Municipales 1er tour du 15 Mars 2020 Candidats au scrutin plurinominal majoritaire Commune : Ablaincourt-Pressoir (Somme) Nombre de sièges à pourvoir : 11 M. BOUREL Didier M. BUSA Vincent Mme DAMAY Amandine M. DOMONT Dany M. GEFFROY Alexandre M. GEFFROY Pascal M. GRASSET Aymeric M. LEGUILLIER Claude Mme NOPPE Isabelle M. SOUVERAIN Guillaume M. THIROUX Olivier Page 2 Elections Municipales 1er tour du 15 Mars 2020 Candidats au scrutin plurinominal majoritaire Commune : Acheux-en-Amiénois (Somme) Nombre de sièges à pourvoir : 15 M. ANDRIEU Dominique M. CASSEL François Mme COTRELLE Valérie M. DETAILLE Alexandre M. DEVAUCHELLE Jean-Paul Mme FRION Jeannette M. GREDIN Damien M. LEFEBVRE Aurélien Mme LEMAIRE Anna Maria M. LENOBLE Olivier M. MARTIN Geoffrey M. RENARD Gilles M. ROUSSEL Bernard Mme ROUSSEL Christine M. SPALLETTI François Page 3 Elections Municipales 1er tour du 15 Mars 2020 Candidats au scrutin plurinominal majoritaire Commune : Acheux-en-Vimeu (Somme) Nombre de sièges à pourvoir : 15 Mme ALAVOINE Isabelle M. ALIX Jérémy M. BENTZ Christophe Mme CARPENTIER Elodie M. DELAPORTE Thibaud M. DUCROCQ Jérôme Mme DUPERREY Sandrine Mme GAILLARD Justine M. GEST Sylvain Mme LOTTIN Claire M. MARTEL Jean-Charles M. POILLY Rémy M. QUAAK Pierre Mme SAOUT-DUTHOIT Genevieve M. VERET Christophe Page 4 Elections Municipales 1er tour du 15 Mars 2020 Candidats au scrutin plurinominal majoritaire Commune : Agenville (Somme) Nombre de sièges à pourvoir : 7 Mme BOULARD Michelle Mme CAPENDU Karine Mme DENEUX Nathalie Mme LEFORT Ludivine Mme MARTIN Ghislaine M. PETIT Dany M.