Congregation Among the Least Religious: the Process and Meaning of Organizing Around Nonbelief

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Board of Directors Meeting Chicago – Hyatt Regency Mccormick Place — May 26, 2016

Board of Directors Meeting Chicago – Hyatt Regency McCormick Place — May 26, 2016 BOARD MEETING MINUTES In attendance: (voting) Rob Boston, Rebecca Hale, John Hooper, Jennifer Kalmanson, Howard Katz, Susan Sackett, Christine Shellska, Herb Silverman, July Simpson, Jason Torpy, Kristin Wintermute, and (non-voting) Roy Speckhardt, Maggie Ardiente, and 15 AHA members and conference attendees. Absent: Anthony Pinn 1. Call to order - Becky called the meeting to order at 8:33am.All AHA board members introduced themselves to those in attendance for the meeting. Howard Katz was appointed parliamentarian. Maggie Ardiente was appointed recording secretary. No new business was added to the agenda. 2. Acceptance/amendment of February meeting minutes - John moved to approve the minutes. Howard seconded. Approved by consensus. 3. Between meetings actions - It was confirmed by the board that the Embassy Suites Charleston will be the location of the 2017 AHA 76th Conference, and that the building fund will be transferred to the Foundation in preparation for imminent building purpose. Jason moved to ratify the votes on removing and adding Humanist Society board members and accept resignations; and the unanimous vote on the strategic plan. Jenny seconded. Approved by consensus. 4. Financial update a. 2015 Audit and 2016 Budget John gave a brief report on the audit and 2016 budget for the AHA. Overall, AHA’s complete assets totals $7.9 million, and that AHA is in a healthy position and on track to meet its goals. Board members were invited to ask questions about the financials. b. The Humanist Foundation - Jenny reports that the Trustees of the Foundation will be meeting in July in Jackson Hole, Wyoming. -

"References." Secular Bodies, Affects and Emotions: European Configurations. Ed. Monique Scheer, Nadia Fadil and Johansen Schepelern Birgitte

"References." Secular Bodies, Affects and Emotions: European Configurations. Ed. Monique Scheer, Nadia Fadil and Johansen Schepelern Birgitte. London,: Bloomsbury Academic, 2019. 221–250. Bloomsbury Collections. Web. 1 Oct. 2021. <http:// dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781350065253.0007>. Downloaded from Bloomsbury Collections, www.bloomsburycollections.com, 1 October 2021, 06:09 UTC. Copyright © Monique Scheer, Nadia Fadil and Birgitte Schepelern Johansen and Contributors 2019. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher, and provide a link to the Creative Commons licence. References Chapter 1 Agrama, H. (2012), Questioning Secularism: Islam, Sovereignty and the Rule of the Law in Modern Egypt, Chicago, IL: Chicago University Press. Anidjar, G. (2003), The Jew, the Arab. A History of the Enemy, Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press. Asad, T. (1979), ‘Anthropology and the Analysis of Ideology’, Man, 14 (4): 607–627. Asad, T. (1982), ‘Anthropological Conceptions of Religion: Reflections on Geertz’, Man, 18 (2): 237–259. Asad, T. (1993), Genealogies of Religion: Discipline and Reason of Power in Christianity and Islam, Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. Asad, T. (2003), Formations of the Secular: Christianity, Islam, Modernity, Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press. Asad, T. (2011), ‘Thinking about the Secular Body, Pain, and Liberal Politics’, Cultural Anthropology, 26 (4): 657–675. Barsalou, L. W. (2008), ‘Grounded Cognition’, Annual Review of Psychology, 59: 617–645. Bear, L. and N. Mathur (2015), ‘Introduction. Remaking the Public Good: A New Anthropology of Bureaucracy’, Cambridge Journal of Anthropology, 33 (1): 18–34. Beckford, J. and A. P. Hampshire (1983), ‘Religious Sects and the Concept of Deviance: The Mormons and the Moonies’, British Journal of Sociology, 34 (2): 208–229. -

Humanism in America Today

Humanism Humanism in America Today Humanism in America Today Summary: Writers and public figures with large audiences have contributed to the increasing popularity of atheism and Humanism in the United States. Thousands of people attended the 2012 Reason Rally, demonstrating the rise of atheism as a political movement, yet many atheists and Humanists experience marginalization within American culture and the challenge of translating a mostly intellectual doctrine into a social movement. On a rainy day in March of 2012, roughly 20,000 people from all parts of the Humanist, atheist, and freethinking movements converged on the National Mall in Washington, D.C. They gathered to celebrate secular values, dispel stereotypes about secular people, and support secular equality. Sponsored by twenty of the country’s major secular organizations, the Reason Rally featured live music and remarks from academics, bloggers, student activists, media personalities, comedians, and two members of Congress, including Representative Pete Stark (D-CA), the first openly atheistic member of Congress. The Reason Rally is evidence of a growing energy and excitement among atheists in America. This new visibility of secularism was inspired in part by the “New Atheists”—including authors such as Richard Dawkins, Sam Harris and Christopher Hitchens—who have pushed the discussion of the potentially dangerous aspects of religion to the forefront of the public discussion. More people than ever are turning away from traditional religious faith, with the Pew Forum on Religion and Public Life reporting that, as of 2014, some 20% of the US population identify as “unaffiliated.” This is particularly true of the rising millennial generation, which has increasingly come to view institutional and traditional religion as associated with conservative social views such as opposition to gay marriage, and is therefore much more skeptical of the role of religion in public life than their parents and grandparents. -

4338 Reason Int CC.Indd

“For my whole Christian life I’ve been saying, ‘My heart cannot rejoice in what my mind rejects.’ Today’s New Atheists seem to be saying something like that: that we should only believe what’s within the bounds of evidence and sound reason. For them, that means we should choose atheism, but in reality nothing could be further from the truth. True Reason explains clearly and deeply how New Atheists have both missed and misunderstood the evidence that exists, and why Christianity is by far the better choice for the thinking mind and worship- ing heart.” —Josh McDowell, Author and Speaker “With a clear message and respectful tone, True Reason challenges and con- vincingly refutes the claim of the New Atheists to own reason. The contribu- tors persuasively argue from history, science, and philosophy that the Christian world view is not only reasonable in itself but also provides the necessary founda- tion for reason. If you love reason, True Reason explains why Christianity is the best worldview for you.” —Michael Licona, PhD, Associate Professor in Theology, Houston Baptist University, Author of The Resurrection of Jesus “More than a year before he joined our staff, Tom Gilson came alongside Ratio Christi to help lead dozens of students to the atheist Reason Rally on the National Mall in Washington, DC. They entered a modern-day ‘lions’ den’ to share Christ’s love and truth, giving away bottles of water and excerpts from True Reason’s first edition. Armed with logic and True Reason, these students engaged in conversation with anyone who would listen. -

The Faith of the Unbeliever

The faith of the unbeliever From time to time we get the impression that our freewheeling Western world is being flooded by a new wave of apostasy. That impression is not quite correct. In reality, that apostasy has become a broad stream, moving unceasingly forward and widening constantly. Sometimes there is a turbulence of sorts in this stream, when the conflict between the Christian faith and unbelief suddenly flares up. This is the case, for example, when it is suggested that the Christians' practice of discriminating against non-Christians, solely because they do not abide by the law of God, should be forbidden. Thus a church may not dismiss a functionary because he is a practicing homosexual, for example. This is also the case when Christians are accused of being undemocratic because they ascribe authority to the Bible. In such cases the mass media can be invoked to stage a sharp confrontation, and the amusement industry is usually ready and willing to be mobilized in an effort to ridicule those foolish Christ-believers. Hatred of the Christian faith is not uncommon in our present society. Appreciation But, you may protest, it is not really that bad, is it? So what if there are some misplaced jokes, if there is a complete misunderstanding of what we are all about. Isn't there also appreciation? Appreciation of faithfulness, reliability, hard work... What, essentially, is the faith of the unbeliever? Unbelievers are people who believe that they can get by well, if not better, without the assumption that what believers call "their God" really exists. -

2013-03-March-Sacram

Special Events Volume 1, Issue 3 March 2013 Fri Mar 1 Movie n Pizza at Sierra College Darwin Day Gala a Success! Fri Mar 1 SAAF meeting and discussion We honored science and the greatest scientific dis- Sat Mar 2 Little Free Library planning covery, natural selection. Lots of tables, including Sun Mar 3 Ancient Chris- ACLU, local groups, Camp Quest, sale of Darwin tian Study Group finger puppets, four electric cars were displayed, the Wed Mar 6 New Member Coffee Meetup Mockingbirds sang sciencey songs in great harmony, Sat Mar 9 SF National and everyone had plenty of cake! Atheist Party Conf. Sat Mar 9 Stockton Dr. Ivan Schwab made interesting points about the eye: Brunch and Atheism Sun Mar 10 Dinosaur Day 1. We needed a ‘file cabinet’ to handle so much sensory Science Fest input, so the brain developed after the eye, not before. Sun Mar 10 Modesto 2. Eyes started when creatures were still ocean dwell- Science on Screen Sun Mar 10 “Hope After ers. That's why our eyes Faith” - Jerry Dewitt need constant lid flap- Fri Mar 15 Stockton ping to keep them wet. Drinking Skeptically Sat Mar 16 Ask an 3. Eyes started as a pro- Atheist - St. Pat’s Parade tein source, using sun- Sat Mar 16 Potluck Game light for energy. Later came a reaction for move- Night Sun Mar 17 JoAnn Anglin ment away from sudden shadows. Poetry Topics 4. Many types of eyes still exist, many much better Sun Mar 17 Blasphemy Breakfast - Rocklin than ours. Some see infrared, like snakes. -

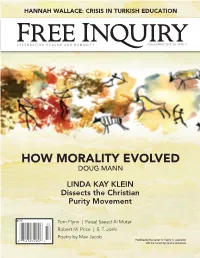

How Morality Evolved Doug Mann

HANNAH WALLACE: CRISIS IN TURKISH EDUCATION CELEBRATING REASON AND HUMANITY February/March 2019 Vol. 39 No. 2 HOW MORALITY EVOLVED DOUG MANN LINDA KAY KLEIN Dissects the Christian Purity Movement F/M 17 $5.95 CDN $5.95 US $5.95 Tom Flynn | Faisal Saeed Al Mutar 03 Robert M. Price | S. T. Joshi Poetry by Max Jacob Published by the Center for Inquiry in association 0 74470 74957 8 with the Council for Secular Humanism For many, mere atheism (the absence of belief in gods and the supernatural) or agnosticism (the view that such questions cannot be answered) aren’t enough. It’s liberating to recognize that supernatural beings are human creations … that there’s no such thing as “spirit” or “transcendence”… that people are undesigned, unintended, and responsible for themselves. But what’s next? Atheism and agnosticism are silent on larger questions of values and meaning. If Meaning in life is not ordained from on high, what small-m meanings can we work out among ourselves? If eternal life is an illusion, how can we make the most of our only lives? As social beings sharing a godless world, how should we coexist? For the questions that remain unanswered after we’ve cleared our minds of gods and souls and spirits, many atheists, agnostics, skeptics, and freethinkers turn to secular humanism. Secular. “Pertaining to the world or things not spiritual or sacred.” Humanism. “Any system of thought or action concerned with the interests or ideals of people … the intellectual and cultural movement … characterized by an emphasis on human interests rather than … religion.” — Webster’s Dictionary Secular humanism is a comprehensive, nonreligious life stance incorporating: A naturalistic philosophy A cosmic outlook rooted in science, and A consequentialist ethical system in which acts are judged not by their conformance to preselected norms but by their consequences for men and women in the world. -

'Neuer Atheismus'

THOMAS ZENK ‘Neuer Atheismus’ ‘New Atheism’ in Germany* Introduction Matthias Knutzen (born 1646 – died after 1674) was some of the characteristics and remarkable traits of the first author we know of who self-identified as an the German discourse on the ‘New Atheism’. Here atheist (Schröder 2010: 8). Before this, the term had we can distinguish between two phases. The Ger solely been used pejoratively to label others. While man media initially characterised ‘New Atheism’ as a Knutzen is almost completely forgotten now, authors rather peculiarly American phenomenon. However, such as Ludwig Feuerbach, Karl Marx, Friedrich it soon came to be understood to be a part of German Nietzsche , or Sigmund Freud are better remembered culture as well. and might even be considered classic writers in the history of the atheist criticism of religion. Whatever may be said about the influence of any one of these The making of a German ‘New Atheism’ authors, there is no doubt that Germany looks back The terms ‘New Atheism’ and ‘New Atheist’ were on a notable history in this field. About a decade ago, originally coined in November 2006 by Gary Wolf, Germany’s capital Berlin was even dubbed ‘the world an American journalist and contributing editor at the capital of atheism’ by the American sociologist Peter lifestyle and technology magazine Wired, in the art L. Berger (2001: 195).1 icle ‘The Church of the NonBelievers’ (Wolf 2006a).3 Given this situation, I am bewildered by the ex Interestingly, only two weeks later, the term ‘New pression ‘New Atheism’.2 Yet, undoubtedly, the term Atheist’ appeared in the German media for the first has become a catchphrase that is commonly used in time.4 In a newspaper article in Die Tageszeitung dat the public discourse of several countries. -

1 Joseph Blankholm Department of Religious Studies University of California, Santa

Joseph Blankholm Department of Religious Studies University of California, Santa Barbara Secularism, Humanism, and Secular Humanism: Terms and Institutions Abstract: This chapter considers recent American attempts to recognize secular humanism as a religion in light of more than a century of debates over the religiosity of secularism and humanism. It offers a history of these terms’ codependent evolution in the United States by focusing on the individuals, groups, and institutions that have adopted them and shaped their meanings. The chapter also argues that those who use these terms today bear forth a fraught and sometimes self-contradicting inheritance. In order to recognize the stakes of contemporary struggles over the meaning and purpose of secularism, one needs a deeper understanding of how the term has come to bear its traces and how it fits within a shifting constellation of labels and concepts. Keywords: Secularism, Humanism, Secular Humanism, Organized Nonbelievers, Secular Activism, Separation of Church and State In October of 2014, a federal district judge in the state of Oregon ruled that secular humanism is a religion, at least for legal purposes involving the Establishment Clause of the U.S. Constitution’s First Amendment. The judge sided with the lawsuits’ plaintiffs, who argued that a humanist inmate at a federal prison should receive certain rights reserved solely for religious groups. The decision arrived a year after the U.S. Army began recognizing humanism as a religious preference, and in the lawsuit’s wake, the Federal Bureau of Prisons granted the same formal recognition. This was not the first time that federal courts have called secular humanism a religion, nor does it settle the question of its religiosity for humanists and their opponents. -

“The Diversity of Nonreligion” NSRN Zurich, Switzerland

DFG Emmy Noether-Project “The Diversity of Nonreligion” Closing Conference & NSRN Annual Conference 2016 July 7 to 9, 2016 Zurich, Switzerland Organized and hostey by “The Diversity of Department of Social Nonreligion & Secularity Nonreligion” Anthropology & Cultural Research Network (NSRN) Studies (ISEK) Conference Program Overview Thursday, July 7, 2016 14:00 Opening ceremony - 14:30 Johannes Quack (University of Zurich) Session I Session II 14:30 Mastiaux Gutkowski - Scheidt Schulz 16:00 16:00 - Coffee break 16:30 Session III Session IV 16:30 - Bullock Hartmann 18:30 Lundmark & LeDrew Kasapoglu Schutz Remmel Dinner & Drinks 20:00 in Zurich Downtown (optional) 2 Friday, July 8, 2016 Session V 09:00 Emmy Noether Project - “The Diversity of Nonreligion” 10:30 (Part I) Discussant: Peter J. Bräunlein (University of Leipzig) 10:30 - Coffee break 11:00 Session VI 11:00 - Emmy Noether Project 12:30 “The Diversity of Nonreligion” (Part II) 12:30 - Lunch break 14:00 Session VII Session VIII 14:00 - Königstedt Lanman 15:30 Pöhls Turpin 15:30 - Coffee break 16:00 16:00 Plenary Session: “Understanding Unbelief” - 17:30 Lee, Lanman, Bullivant & Farias1 17:30 - Coffee break 18:00 Conference Keynote Lecture 18:00 “The Demarcation of Boundaries: - How to Approach Secularity and Non-Religion” 19:00 Monika Wohlrab-Sahr (University of Leipzig) 20:00 Conference dinner 1 Co-authors Stephen Bullivant and Miguel Farias will not be present. 3 Saturday, July 9, 2016 Session IX Session X 09:30 - Ben Slima Begum 11:00 Lee Popp-Baier 11:00 - Coffee break 11:30 -

The Birth and Death of God from Mesopotamia to Postmodernity 840:115:92 Online Course, Spring 2015

The Birth and Death of God from Mesopotamia to Postmodernity 840:115:92 online course, Spring 2015 Professor Ballentine [email protected] office: Loree gym 132 office hour: Wednesdays 12pm or by appointment online office hour: Fridays 121pm via Sakai chat room Across the Humanities, we study human cultural products. The academic study of religion focuses on human cultural products that pertain to entities, places, and things that are presented as transcendent, divine, sacred, holy, otherworldly, universal, etc. This course analyzes diverse characterizations of gods, from our earliest Mesopotamian myths, through early Jewish, Christian, and Muslim theologies, Medieval times, the Enlightenment, Modernity, and into Postmodernity. How have divine beings been characterized? How has the idea of god developed over time, and in relation to what cultural developments? We will begin with how gods are born in ancient Near Eastern traditions, how gods are organized into family and political structures in ancient pantheons, and the notion of there being one “Most High” god who is king of other divine beings. We will continue with early Jewish, Christian, and Muslim descriptions of god, identifying continuity with ancient Mediterranean theologies and innovations throughout late antiquity and into the middle ages. From the Renaissance and into the modern period, European developments in philosophy and science, which were thoroughly intertwined, led to changing conceptions of god and the role of the divine in the human world. Finally, in contemporary secular societies there are vast notions of gods and God, including views labeled: antitheism, atheism, agnosticism, pantheism, polytheism, theism, and monotheism. We will trace the history of these concepts, analyzing how the longheld conception of the cosmos as full of divine beings is related to more recent conceptions of a cosmos with only one god, or alternatively, no gods at all. -

Atheism AO1 Handout Part 1

Philosophy Of Religion / Atheism AO1 Atheism AO1 Handout Part 1 THE IDEA: The difference between atheism and agnosticism: ‘Atheism’ comes from the Greek word meaning “without God” and describes the position of those who reject belief in God or gods. There are various shades of atheism. The term ‘agnostic’ was first used by the English biologist Thomas Huxley. The word is derived from the Greek, meaning ‘without knowledge’. Agnosticism embraces the idea that the existence of God or any other ultimate reality is, in principle, unknowable. Our knowledge is limited and we cannot know ultimate reasons for things. It is not that the evidence is lacking, it is that the evidence is never possible. Some use the word differently. Agnosticism is commonly used to indicate a suspension of the decision to accept or reject belief in God. The suspension lasts until we have more data. QUOTES 1. “Atheism is the religion of the autonomous and rational human being, who believes that reason is able to uncover and express the deepest truths of the universe. “ (Alister McGrath) 2. “I invented the word “agnostic” to denote people who, like myself, confess themselves to be hopelessly ignorant concerning a variety of matters about which metaphysicians and theologians dogmatise with utmost confidence.” (Thomas Huxley) 3. “They were quite sure that they had attained a certain “gnosis”--had more or less successfully solved the problem of existence; while I was quite sure I had not, and had a pretty strong conviction that the problem was insoluble. “ (Thomas Huxley) 4. “If ‘faith’ is defined as ‘lying beyond proof’, both Christianity and atheism are faiths.” (Alister McGrath) 5.