The Sociology of the Sunday Assembly: ‘Belonging Without Believing’ in a Post- Christian Context Josh BULLOCK

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

"References." Secular Bodies, Affects and Emotions: European Configurations. Ed. Monique Scheer, Nadia Fadil and Johansen Schepelern Birgitte

"References." Secular Bodies, Affects and Emotions: European Configurations. Ed. Monique Scheer, Nadia Fadil and Johansen Schepelern Birgitte. London,: Bloomsbury Academic, 2019. 221–250. Bloomsbury Collections. Web. 1 Oct. 2021. <http:// dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781350065253.0007>. Downloaded from Bloomsbury Collections, www.bloomsburycollections.com, 1 October 2021, 06:09 UTC. Copyright © Monique Scheer, Nadia Fadil and Birgitte Schepelern Johansen and Contributors 2019. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher, and provide a link to the Creative Commons licence. References Chapter 1 Agrama, H. (2012), Questioning Secularism: Islam, Sovereignty and the Rule of the Law in Modern Egypt, Chicago, IL: Chicago University Press. Anidjar, G. (2003), The Jew, the Arab. A History of the Enemy, Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press. Asad, T. (1979), ‘Anthropology and the Analysis of Ideology’, Man, 14 (4): 607–627. Asad, T. (1982), ‘Anthropological Conceptions of Religion: Reflections on Geertz’, Man, 18 (2): 237–259. Asad, T. (1993), Genealogies of Religion: Discipline and Reason of Power in Christianity and Islam, Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. Asad, T. (2003), Formations of the Secular: Christianity, Islam, Modernity, Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press. Asad, T. (2011), ‘Thinking about the Secular Body, Pain, and Liberal Politics’, Cultural Anthropology, 26 (4): 657–675. Barsalou, L. W. (2008), ‘Grounded Cognition’, Annual Review of Psychology, 59: 617–645. Bear, L. and N. Mathur (2015), ‘Introduction. Remaking the Public Good: A New Anthropology of Bureaucracy’, Cambridge Journal of Anthropology, 33 (1): 18–34. Beckford, J. and A. P. Hampshire (1983), ‘Religious Sects and the Concept of Deviance: The Mormons and the Moonies’, British Journal of Sociology, 34 (2): 208–229. -

Nonreligion and Secularity in Canada Introduction

Secular Studies 3 (2021) 1–6 brill.com/secu Nonreligion and Secularity in Canada Introduction Zachary A. Munro Department of Sociology and Legal Studies, University of Waterloo, Waterloo, ON, Canada [email protected] Sarah Wilkins-Laflamme University of Waterloo, Waterloo, ON, Canada [email protected] This special issue of Secular Studies critically engages with key theoretical debates in nonreligion and secularity studies and contributes to a growing body of empirical research on the Canadian secular landscape. Having gained increasing attention from scholars over the past two decades, there is now a growing body of research in the subfield of nonreligion and secular studies. Notable focuses have been on nonreligious communities, such as the Sunday Assembly (e.g. Cross 2017; Smith 2017; Mortimer, Tim, and Melanie Prideaux 2018), nonreligious identities (e.g. Hacket 2014; Lanman et al. 2019; Lee 2014, 2015; Manning 2015; Sumerau and Cragun 2016; Voas and Day 2010; Zucker- man and Shook 2017), irreligious disaffiliation (e.g. Nica 2020; Thiessen and Wilkins-Laflamme 2017; Zuckerman 2012), political polarization (Baker and Smith 2015; Wilkins-Laflamme 2016), and on how the nonreligious meaning- fully differ from their religious counterparts in values and life behaviors (Man- ning 2015; Thiessen and Wilkins-Laflamme 2020; Zuckerman 2008, 2014). Further existing research has engaged with theoretical debates regarding the categories of ‘nonreligion’ and ‘secularity’ (Lee 2012, 2014, 2015; Quack 2014; Quack and Schuch 2017; Quack et al. 2020) and potential replacement cate- gories, such as ‘worldview’ and ‘meaning makings systems’ (Taves 2020; Taves et al. 2018) or ‘cosmic belief systems’ (Baker and Smith 2015), as well as the multiplicity of secularities (Lee 2015; 2019; Taylor 2007; Wohlrab-Sahr and Bur- chardt 2012). -

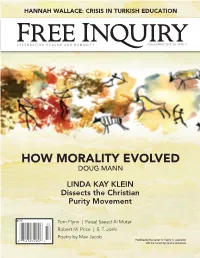

How Morality Evolved Doug Mann

HANNAH WALLACE: CRISIS IN TURKISH EDUCATION CELEBRATING REASON AND HUMANITY February/March 2019 Vol. 39 No. 2 HOW MORALITY EVOLVED DOUG MANN LINDA KAY KLEIN Dissects the Christian Purity Movement F/M 17 $5.95 CDN $5.95 US $5.95 Tom Flynn | Faisal Saeed Al Mutar 03 Robert M. Price | S. T. Joshi Poetry by Max Jacob Published by the Center for Inquiry in association 0 74470 74957 8 with the Council for Secular Humanism For many, mere atheism (the absence of belief in gods and the supernatural) or agnosticism (the view that such questions cannot be answered) aren’t enough. It’s liberating to recognize that supernatural beings are human creations … that there’s no such thing as “spirit” or “transcendence”… that people are undesigned, unintended, and responsible for themselves. But what’s next? Atheism and agnosticism are silent on larger questions of values and meaning. If Meaning in life is not ordained from on high, what small-m meanings can we work out among ourselves? If eternal life is an illusion, how can we make the most of our only lives? As social beings sharing a godless world, how should we coexist? For the questions that remain unanswered after we’ve cleared our minds of gods and souls and spirits, many atheists, agnostics, skeptics, and freethinkers turn to secular humanism. Secular. “Pertaining to the world or things not spiritual or sacred.” Humanism. “Any system of thought or action concerned with the interests or ideals of people … the intellectual and cultural movement … characterized by an emphasis on human interests rather than … religion.” — Webster’s Dictionary Secular humanism is a comprehensive, nonreligious life stance incorporating: A naturalistic philosophy A cosmic outlook rooted in science, and A consequentialist ethical system in which acts are judged not by their conformance to preselected norms but by their consequences for men and women in the world. -

“The Diversity of Nonreligion” NSRN Zurich, Switzerland

DFG Emmy Noether-Project “The Diversity of Nonreligion” Closing Conference & NSRN Annual Conference 2016 July 7 to 9, 2016 Zurich, Switzerland Organized and hostey by “The Diversity of Department of Social Nonreligion & Secularity Nonreligion” Anthropology & Cultural Research Network (NSRN) Studies (ISEK) Conference Program Overview Thursday, July 7, 2016 14:00 Opening ceremony - 14:30 Johannes Quack (University of Zurich) Session I Session II 14:30 Mastiaux Gutkowski - Scheidt Schulz 16:00 16:00 - Coffee break 16:30 Session III Session IV 16:30 - Bullock Hartmann 18:30 Lundmark & LeDrew Kasapoglu Schutz Remmel Dinner & Drinks 20:00 in Zurich Downtown (optional) 2 Friday, July 8, 2016 Session V 09:00 Emmy Noether Project - “The Diversity of Nonreligion” 10:30 (Part I) Discussant: Peter J. Bräunlein (University of Leipzig) 10:30 - Coffee break 11:00 Session VI 11:00 - Emmy Noether Project 12:30 “The Diversity of Nonreligion” (Part II) 12:30 - Lunch break 14:00 Session VII Session VIII 14:00 - Königstedt Lanman 15:30 Pöhls Turpin 15:30 - Coffee break 16:00 16:00 Plenary Session: “Understanding Unbelief” - 17:30 Lee, Lanman, Bullivant & Farias1 17:30 - Coffee break 18:00 Conference Keynote Lecture 18:00 “The Demarcation of Boundaries: - How to Approach Secularity and Non-Religion” 19:00 Monika Wohlrab-Sahr (University of Leipzig) 20:00 Conference dinner 1 Co-authors Stephen Bullivant and Miguel Farias will not be present. 3 Saturday, July 9, 2016 Session IX Session X 09:30 - Ben Slima Begum 11:00 Lee Popp-Baier 11:00 - Coffee break 11:30 -

Eric Perl's Theophanism: an Option for Agnostics?

religions Article Eric Perl’s Theophanism: An Option for Agnostics? Travis Dumsday Department of Philosophy & Religious Studies, Concordia University of Edmonton, Edmonton, AB T5B 4E4, Canada; [email protected] Received: 1 May 2020; Accepted: 15 May 2020; Published: 19 May 2020 Abstract: Recent work in analytic philosophy of religion has seen increased interest in nontheistic, but still non-naturalist (indeed, broadly religious) worldview options. J.L. Schellenberg’s Ultimism has been among the most prominent of these. Another interesting option that has yet to receive much attention is the Theophanism advocated by the Neoplatonism scholar Eric Perl. In this paper, I summarize Perl’s theophanism (which he describes as being neither theistic nor atheistic) and assess it on two fronts: (a) whether it might be an acceptable philosophical option for agnostics, specifically, and (b) to what extent it is independently defensible philosophically. Keywords: agnosticism; atheism; theism; God; Neoplatonism; Perl; Eric; orthodoxy 1. Introduction The subfield that is analytic philosophy of religion remains focused primarily on issues pertaining to two competing perspectives or worldviews: metaphysical naturalism (MN) and Judeo-Christian theism (JCT). Insofar as MN maintains that the only irreducible kinds of reality are essentially physical in character (perhaps spacetime plus fundamental particles or fields), it is seen today as inherently atheistic.1 JCT stands as something of a polar opposite, affirming not only a personal, necessarily existent and spiritual OmniGod (a divinity who is essentially omnipotent, omniscient, and omnibenevolent) but also the reality of other irreducibly spiritual entities (like human souls) and nonphysical causal processes (like miracles). Thus, the dispute between MN and JCT involves a good deal more than just the debate over the existence of God, even if that remains the core dividing line between them. -

The Sunday Assembly, 9781451478204, 344 Pages, 2008, Augsburg Fortress, 2008, Lorraine S

The Sunday Assembly, 9781451478204, 344 pages, 2008, Augsburg Fortress, 2008, Lorraine S. Brugh, Gordon W. Lathrop The Sunday Assembly. 12,286 likes · 7 talking about this. The Sunday Assembly is a worldwide network of secular congregations that meet locally to hear... Book. The Oasis Network. Nonprofit Organization. Seattle Atheist Church. For us, it's receiving this video from Sunday Assembly Pittsburgh who are gearing up for their first ever Sunday Assembly on Sept 28th and just wanted to say hi! If you want to be part of this merry band of Pittsburgh people or just want to say hi back, check out their Facebook page! 52. The Sunday Assembly addresses the general principles that have guided the shaping of Evangelical Lutheran Worship, considering that central liturgy of Christian worship, Holy Communion. This text examines how worship interacts with environment, music and the preached word, and features useful and practical suggestions for all those who lead the assembly in worship around word and table. Read More. Publisher Book Preview. The Sunday Assembly - Lorraine S. Brugh. You've reached the end of this preview. Sign up to read more! The Sunday Assembly book. Read reviews from world’s largest community for readers. Goodreads helps you keep track of books you want to read. Start by marking “The Sunday Assembly (Using Evangelical Lutheran Worship, Vol. 1)†as Want to Read: Want to Read saving… Want to Read. Currently Reading. Read. Other editions. Enlarge cover. Sunday Assembly is a non-religious gathering co-founded by Sanderson Jones and Pippa Evans in January 2013 in London, England. -

Religious London Faith in a Global City

Report Religious London Faith in a global city Paul Bickley and Nathan Mladin Theos is the UK’s leading religion and society think tank. It has a broad Christian basis and exists to enrich the conversation about the role of faith in society through research, events, and media commentary. Published by Theos in 2020 Scripture quotations are from the © Theos New Revised Standard Version, copyright © 1989 the Division of ISBN 978-1-9996680-2-0 Christian Education of the National Some rights reserved. See copyright Council of the Churches of Christ in licence for details. For further the United States of America. Used information and subscription details by permission. All rights reserved. please contact: Theos Licence Department +44 (0) 20 7828 7777 77 Great Peter Street [email protected] London SW1P 2EZ theosthinktank.co.uk Report Religious London Faith in a global city Paul Bickley and Nathan Mladin Religious London I journeyed to London, to the timekept City, Where the River flows, with foreign flotations. There I was told: we have too many churches, And too few chop-houses. There I was told: Let the vicars retire. Men do not need the Church In the place where they work, but where they spend their Sundays. In the City, we need no bells: Let them waken the suburbs. T.S. Eliot, Choruses from “The Rock” 2 Acknowledgements 3 Religious London We would like to offer thanks to individuals and organisations that have encouraged, supported or assisted on this project. The generous support of The Mercers’ Company enabled this research. Conversations with a number of individuals – Ben Judah, Professor Tony Travers, Professor Grace Davie (who had already broken some of this ground in a previous Theos report), the Rev Dr David Goodhew, and Dr Andrew Rogers – inspired us to explore our theme in greater depth. -

Introduction

Ryan Cragun &Christel Manning Introduction What would happen to ahighschool senior deep in the bible belt of the United States if they told theirhighschool administrators thatthey would contact the AmericanCivil LibertiesUnion (ACLU) if the school had aprayerathis high school graduation?This isn’tahypothetical scenario – it happened in 2011. Damon Fowler,asenior at Bastrop High School in Louisiana, informed the su- perintendent of the school district that he knew school-sponsored prayer was il- legal and that he would contact the ACLU if the school went ahead with aplan- ned, school-sponsored prayer at the graduation ceremony. Damon’sthreat was leaked to the public. What followed weredeath threats from community mem- bers and fellow students, weeks of harassment,and eventuallyhis parents dis- owning him and kicking him out of their home. One more thing happened, which is whywerecount this story at the begin- ning of this book on organized secularism: the secular community came together to support Damon. As his story made its wayinto the local, national, and even- tuallyinternational press,nonreligious¹ and/or secular individuals made offers of aplace to stay, protection,and transportation, and acollegefund was set up for Damon since his parents had cut him off financially. Various secular or- ganizations explicitlyoffered Damon help. The Freedom From Religion Founda- tion gave him a$1,000 collegescholarship and other organizations volunteered to help him legally. Damon’sstory should be surprising in acountry that prides itself as amelt- ing pot of races,ethnicities, cultures, and religions. Yet, it is alsoanot entirely uncommon scenario in the United States, whereatheists’ moralityisesteemed at about the same level as is rapists’ (Gervais,Shariff, and Norenzayan2011) and onlyabout 50%ofAmericans would vote for an atheist for President (Edgell, Gerteis,and Hartmann 2006). -

Modern but Not Meaningless: Nonreligious Cultures and Communities in the United States

Modern but Not Meaningless: Nonreligious Cultures and Communities in the United States A Dissertation SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Jacqueline Frost IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Penny Edgell, Advisor June 2020 Modern but Not Meaningless: Nonreligious Cultures and Communities in the United States © 2020 by Jacqueline Frost All rights reserved Acknowledgements This dissertation is the product of support and feedback from numerous mentors, colleagues, friends, family members, and community members. First, I would like to thank the nonreligious people who participated in my project, especially the members of the Minneapolis/St. Paul chapter of the Sunday Assembly. Without their willingness to welcome me into their community, share their stories with me, and provide continuous feedback on my research questions, this project would not have been possible. I am forever grateful to everyone who took time out of their day to sit with me for interviews, who shared their nonreligious narratives with me, and who allowed me to document the often difficult, vulnerable, and emotional process of building community and ritual. Their kindness and openness allowed me to shed new light on the increasingly diverse population of atheists, agnostics, and “nothing in particulars” that make up the growing nonreligious demographic in the United States. I hope this dissertation adequately conveys the passion and dedication with which so many nonreligious people are working to improve their communities and create meaning in our complex world. This dissertation would also not have been possible without my advisor, Penny Edgell. Words cannot fully express what Penny’s mentorship has meant to me and the thousands of ways, both big and small, that her support and guidance have made me a better scholar, teacher, and writer. -

A Godless Community an Exploratory Study on the Sunday Assembly and Its Attendees

A godless community An exploratory study on the Sunday Assembly and its attendees Emma Binnendijk 10830928 Supervisor: mw. dr. U.L. Popp-Baier Second reader: mw. dr. C. Ivanescu Master Thesis Research Master Religious Studies University of Amsterdam June 2020 Table of contents Introduction 1 1. Theoretical Framework 6 1.1. History of the concept of non-religion 6 1.2. History of the concept of belief 16 1.3. Conclusion 23 2. Method 24 2.1. Participant observation 24 2.2. Sampling of respondents 25 2.3. Interviews 27 2.4. Coding & Analysis 30 2.5. Conclusion 30 3. The Sunday Assembly 32 3.1. History and vision of the Sunday Assembly 32 3.2. The meetings 35 3.3. An impression of a meeting 37 3.4. Conclusion 41 4. Analysis of the interviews 42 4.1. About the interviews and respondents 42 4.2. Why do people attend the Sunday Assembly? 43 4.3. The orientation and dimensions of the respondents’ beliefs 45 4.4. The Sunday Assembly’s values and their appraisal 59 4.5. Conclusion 64 Final Conclusion and Discussion 66 Bibliography 73 Appendix I: Dutch translation of the interview questions 77 Introduction Throughout the Western world, interest in religion is rising amongst a-religious people. People are looking for ways to enjoy the merits of religion without the God that was traditionally used to define religion in the Western world. A famous proponent of religion for atheists is Alain de Botton. He argues in his book Religion for Atheists that religion has a lot to offer for secular societies. -

1 Religious Beliefs and Philosophical Views

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Oxford Brookes University: RADAR Religious beliefs and philosophical views: A qualitative study Helen De Cruz, Oxford Brookes University This is a draft. Please find the final version in Res Philosophica. Abstract Philosophy of religion is often regarded as a philosophical discipline in which irrelevant influences, such as upbringing and education, play a pernicious role. This paper presents results of a qualitative survey among academic philosophers of religion to examine the role of such factors in their work. In light of these findings, I address two questions: an empirical one (whether philosophers of religion are influenced by irrelevant factors in forming their philosophical attitudes) and an epistemological one (whether the influence of irrelevant factors on our philosophical views should worry us). My answer to the first question is a definite yes, my answer to the second, a tentative yes. 1. Introduction Philosophers value rational belief-formation, in particular, if it concerns their philosophical views. Authors such as Descartes (1641/1992) and al-Ghazālī (1100/1952) thought it was possible to cast off the preconceptions they grew up with. Descartes likened the beliefs an adult has acquired since childhood to apples one can cast out of a basket one by one, to critically examine which ones are rotten and which ones are sound. Al-Ghazālī wrote in his autobiographical defense of Sufi mysticism that he started questioning the beliefs he acquired through his parents the moment he realized their pervasive influence in how religious views are formed: .. -

Religious Beliefs and Philosophical Views

RELIGIOUS BELIEFS AND PHILOSOPHICAL VIEWS: AQUALITATIVE STUDY Helen De Cruz Abstract: Philosophy of religion is often regarded as a philosophical discipline in which irrelevant influences, such as upbringing and education, play a pernicious role. This paper presents results of a qualitative survey among academic philosophers of religion to examine the role of such factors in their work. In light of these findings, I address two questions: an empirical one (whether philoso- phers of religion are influenced by irrelevant factors in forming their philosophical attitudes) and an epistemo- logical one (whether the influence of irrelevant factors on our philosophical views should worry us). My answer to the first question is a definite yes, and my answer to the second one is a tentative yes. 1 Introduction Philosophers value rational belief-formation, in particular, if it concerns their philosophical views. Authors such as Descartes (1641 [1992]) and al-Ghazal¯ ı¯ (ca.1100 [1952]) thought it was possible to cast off the pre- conceptions they grew up with. Descartes likened the beliefs an adult has acquired since childhood to apples one can cast out of a basket one by one, to critically examine which ones are rotten and which ones are sound. Al-Ghazal¯ ı¯ wrote in his autobiographical defense of Sufi mysticism that he started questioning the beliefs he acquired through his parents the moment he realized their pervasive influence in how religious views are formed: As I drew near the age of adolescence the bonds of mere authority (taql¯ıd) ceased to hold me and inherited beliefs lost their grip upon me, for I saw that Christian youths always grew up to be Christians, Jewish youths to be Jews and Muslim youths to be Muslims.