1 Chris Jafta Constitutional Court Oral History Project 2Nd December 2011

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Appointments to South Africa's Constitutional Court Since 1994

Durham Research Online Deposited in DRO: 15 July 2015 Version of attached le: Accepted Version Peer-review status of attached le: Peer-reviewed Citation for published item: Johnson, Rachel E. (2014) 'Women as a sign of the new? Appointments to the South Africa's Constitutional Court since 1994.', Politics gender., 10 (4). pp. 595-621. Further information on publisher's website: http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S1743923X14000439 Publisher's copyright statement: c Copyright The Women and Politics Research Section of the American 2014. This paper has been published in a revised form, subsequent to editorial input by Cambridge University Press in 'Politics gender' (10: 4 (2014) 595-621) http://journals.cambridge.org/action/displayJournal?jid=PAG Additional information: Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in DRO • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full DRO policy for further details. Durham University Library, Stockton Road, Durham DH1 3LY, United Kingdom Tel : +44 (0)191 334 3042 | Fax : +44 (0)191 334 2971 https://dro.dur.ac.uk Rachel E. Johnson, Politics & Gender, Vol. 10, Issue 4 (2014), pp 595-621. Women as a Sign of the New? Appointments to South Africa’s Constitutional Court since 1994. -

Faculty of Health Sciences, Walter Sisulu University: Training Doctors from and for Rural South African Communities

Original Scientific Articles Medical Education Faculty of Health Sciences, Walter Sisulu University: Training Doctors from and for Rural South African Communities Jehu E. Iputo, MBChB, PhD ABSTRACT Outcomes To date, 745 doctors (72% black Africans) have graduated Introduction The South African health system has disturbing in- from the program, and 511 students (83% black Africans) are currently equalities, namely few black doctors, a wide divide between urban enrolled. After the PBL/CBE curriculum was adopted, the attrition rate and rural sectors, and also between private and public services. Most for black students dropped from 23% to <10%. The progression rate medical training programs in the country consider only applicants with rose from 67% to >80%, and the proportion of students graduating higher-grade preparation in mathematics and physical science, while within the minimum period rose from 55% to >70%. Many graduates most secondary schools in black communities have limited capacity are still completing internships or post-graduate training, but prelimi- to teach these subjects and offer them at standard grade level. The nary research shows that 36% percent of graduates practice in small Faculty of Health Sciences at Walter Sisulu University (WSU) was towns and rural settings. Further research is underway to evaluate established in 1985 to help address these inequities and to produce the impact of their training on health services in rural Eastern Cape physicians capable of providing quality health care in rural South Af- Province and elsewhere in South Africa. rican communities. Conclusions The WSU program increased access to medical edu- Intervention Access to the physician training program was broad- cation for black students who lacked opportunities to take advanced ened by admitting students who obtained at least Grade C (60%) in math and science courses prior to enrolling in medical school. -

Download 2014 Annual Report

Faculty of Law 2014 Centre for ANNUAL Faculty of Law Human Rights REPORT 2 The Centre for Human Rights, based at the Faculty of Law, CONTENTS University of Pretoria, is both an academic department and a non- DIRECTOR’S MESSAGE 4 governmental organisation. ACADEMIC PROGRAMMES 6 The Centre was established in the Faculty of Law, University of Pretoria, in 1986, as part of domestic efforts against the apartheid system of the time. RESEARCH 8 The Centre for Human Rights works towards human rights education in Africa, a greater awareness of human rights, the wide dissemination of publications on human rights in Africa, and the improvement of the PROJECTS 10 rights of women, people living with HIV, indigenous peoples, sexual minorities and other disadvantaged or marginalised persons or groups across the continent. PUBLICATIONS 31 Over the years, the Centre has positioned itself in an unmatched network of practising and academic lawyers, national and international civil servants and human rights practitioners across the entire continent, with a CENTRE PERSONNEL 33 specific focus on human rights law in Africa, and international development law in general. Today, a wide network of Centre alumni contribute in numerous ways to the advancement and strengthening STAFF ACTIVITES 36 of human rights and democracy all over the Africa continent, and even further afield. FUNDING 40 In 2006, the Centre for Human Rights was awarded the UNESCO Prize for Human Rights Education, with particular recognition for the African Human Rights Moot Court Competition and the LLM in Human Rights and Democratisation in Africa. In 2012, the Centre for Human Rights was awarded the 2012 African Union Human Rights Prize. -

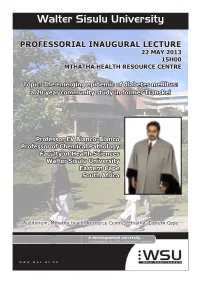

Walter Sisulu University

Walter Sisulu University PROFESSORIAL INAUGURAL LECTURE 22 MAY 2013 15H00 MTHATHA HEALTH RESOURCE CENTRE Topic: The emerging epidemic of diabetes mellitus: a 20 year community study in former Transkei Professor EV Blanco-Blanco Professor of Chemical Pathology Faculty of Health Sciences Walter Sisulu University Eastern Cape South Africa Auditorium, Mthatha Health Resource Centre, Mthatha, Eastern Cape www.wsu.ac.za WALTER SISULU UNIVERSITY (WSU) DEPARTMENT OF CHEMICAL PATHOLOGY SCHOOL OF MEDICINE FACULTY OF HEALTH SCIENCES TOPIC “THE EMERGING EPIDEMIC OF DIABETES MELLITUS: A 20-YEAR COMMUNITY STUDY IN THE FORMER TRANSKEI” BY ERNESTO V. BLANCO-BLANCO PROFESSOR OF CHEMICAL PATHOLOGY DATE: 22 MAY 2013 VENUE: UMTATA HEALTH RESOURCE CENTRE 3 4 INTRODUCTION AND TOPIC MOTIVATION DIABETES MELLITUS Definition Historical background CLASSIFICATION OF DIABETES MELLITUS DIAGNOSIS OF DIABETES MELLITUS RISK FACTORS AND PREDISPOSING CONDITIONS FOR DIABETES COMPLICATIONS OF DIABETES MELLITUS THE GLOBAL PREVALENCE & GLOBAL BURDEN OF DIABETES THE AFRICAN BURDEN OF DIABETES MELLITUS THE SOUTH AFRICAN BURDEN OF DIABETES MELLITUS CONSEQUENCES OF THE BURDEN OF DIABETES IMPLICATIONS OF THE BURDEN OF DIABETES FOR HEALTH PLANNING DIABETES PREVENTION AS STRATEGY CONTROL OF THE CURRENT BURDEN OF DIABETES CONCLUSIONS REFERENCES 5 INTRODUCTION AND TOPIC MOTIVATION Chemical Pathology, Diabetes Mellitus and the Former Transkei I am a Chemical Pathologist by training. The term ‘pathology’ derives from the Greek words “pathos” meaning “disease” and “logos” meaning “a treatise”. Pathology is a major field of Medicine that deals with the essential nature of diseases, their processes and consequences. A medical doctor that specializes in pathology is known as ‘a pathologist’. Chemical Pathology is that branch of Pathology, which deals specially with the biochemical basis of diseases and the use of biochemical tests carried out at hospital laboratories on the blood and other body fluids to provide support to clinicians. -

The Power of Heritage to the People

How history Make the ARTS your BUSINESS becomes heritage Milestones in the national heritage programme The power of heritage to the people New poetry by Keorapetse Kgositsile, Interview with Sonwabile Mancotywa Barbara Schreiner and Frank Meintjies The Work of Art in a Changing Light: focus on Pitika Ntuli Exclusive book excerpt from Robert Sobukwe, in a class of his own ARTivist Magazine by Thami ka Plaatjie Issue 1 Vol. 1 2013 ISSN 2307-6577 01 heritage edition 9 772307 657003 Vusithemba Ndima He lectured at UNISA and joined DACST in 1997. He soon rose to Chief Director of Heritage. He was appointed DDG of Heritage and Archives in 2013 at DAC (Department of editorial Arts and Culture). Adv. Sonwabile Mancotywa He studied Law at the University of Transkei elcome to the Artivist. An artivist according to and was a student activist, became the Wikipedia is a portmanteau word combining youngest MEC in Arts and Culture. He was “art” and “activist”. appointed the first CEO of the National W Heritage Council. In It’s Bigger Than Hip Hop by M.K. Asante. Jr Asante writes that the artivist “merges commitment to freedom and Thami Ka Plaatjie justice with the pen, the lens, the brush, the voice, the body He is a political activist and leader, an and the imagination. The artivist knows that to make an academic, a historian and a writer. He is a observation is to have an obligation.” former history lecturer and registrar at Vista University. He was deputy chairperson of the SABC Board. He heads the Pan African In the South African context this also means that we cannot Foundation. -

Unrevised Hansard National

UNREVISED HANSARD NATIONAL ASSEMBLY TUESDAY, 13 JUNE 2017 Page: 1 TUESDAY, 13 JUNE 2017 ____ PROCEEDINGS OF THE NATIONAL ASSEMBLY ____ The House met at 14:02. The Speaker took the Chair and requested members to observe a moment of silence for prayer or meditation. MOTION OF CONDOLENCE (The late Ahmed Mohamed Kathrada) The CHIEF WHIP OF THE MAJORITY PARTY: Hon Speaker I move the Draft Resolution printed in my name on the Oder Paper as follows: That the House — UNREVISED HANSARD NATIONAL ASSEMBLY TUESDAY, 13 JUNE 2017 Page: 2 (1) notes with sadness the passing of Isithwalandwe Ahmed Mohamed Kathrada on 28 March 2017, known as uncle Kathy, following a short period of illness; (2) further notes that Uncle Kathy became politically conscious when he was 17 years old and participated in the Passive Resistance Campaign of the South African Indian Congress; and that he was later arrested; (3) remembers that in the 1940‘s, his political activities against the apartheid regime intensified, culminating in his banning in 1954; (4) further remembers that in 1956, our leader, Kathrada was amongst the 156 Treason Trialists together with Nelson Mandela and Walter Sisulu, who were later acquitted; (5) understands that he was banned and placed under a number of house arrests, after which he joined the political underground to continue his political work; UNREVISED HANSARD NATIONAL ASSEMBLY TUESDAY, 13 JUNE 2017 Page: 3 (6) further understands that he was also one of the eight Rivonia Trialists of 1963, after being arrested in a police swoop of the Liliesleaf -

Top Court Trims Executive Power Over Hawks

Legalbrief | your legal news hub Sunday 26 September 2021 Top court trims executive power over Hawks The Constitutional Court has not only agreed that legislation governing the Hawks does not provide adequate independence for the corruption-busting unit, it has 'deleted' the defective sections, notes Legalbrief. It found parts of the legislation that governs the specialist corruption-busting body unconstitutional, because they did not sufficiently insulate it from potential executive interference. This, notes a Business Day report, is the second time the court has found the legislation governing the Hawks, which replaced the Scorpions, unconstitutional for not being independent enough. The first time, the court sent it back to Parliament to fix. This time the court did the fixing, by cutting out the offending words and sections. The report says the idea behind the surgery on the South African Police Service (SAPS) Act was to ensure it had sufficient structural and operational independence, a constitutional requirement. In a majority judgment, Chief Justice Mogoeng Mogoeng said: 'Our anti-corruption agency is not required to be absolutely independent. It, however, has to be adequately independent. 'And that must be evidenced by both its structural and operational autonomy.' The judgment resolved two cases initially brought separately - one by businessman Hugh Glenister, the other by the Helen Suzman Foundation (HSF), notes Business Day. Because both cases challenged the Hawks legislation on the grounds of independence, the two were joined. Glenister's case - that the Hawks could never be independent while located in the SAPS, which was rife with corruption - was rejected by the court. -

JSC Rejects Hlophe Bid for Recusal of Five Members

Legalbrief | your legal news hub Thursday 30 September 2021 JSC rejects Hlophe bid for recusal of five members The Judicial Service Commission (JSC) will for the first time hold an inquiry that could be the prelude to the impeachment of a judge, after it rejected a request that five of its members should recuse themselves, says a report in the The Sunday Independent. The JSC, which met at the weekend to consider the complaints by the Constitutional Court and Cape Judge President John Hlophe, found that in view of the 'conflict of fact' on papers before it, oral evidence would be required from both sides. The report quotes an unnamed leading senior counsel as saying: 'The inquiry that is going to be held is of huge importance. If this matter is proved, it is difficult to imagine anything more serious.' The request for recusal by counsel for Hlophe was based on concerns that he would not get a fair hearing because last year the five had felt the Judge President should face a gross misconduct inquiry relating to his 'moonlighting' for the Oasis group of companies. At the time, during the Oasis matter, the JSC had been split largely on racial lines, and it was Chief Justice Pius Langa who cast the deciding vote that saw Hlophe escape an inquiry that could have led to his impeachment. According to a report on the News24 site, JSC spokesperson Marumo Moerane said both parties made presentations regarding the future conduct of the matter. He said notice of the date and venue of the oral hearing would be made known once arrangements had been finalised. -

A Brief History of the North West Bar Association

THE BAR IN SA was a circuit court. This led to an arrangement being made between the A brief history of the North West Bar and advocates who were employed Bar Association as lecturers at the Law Faculty of the newly established University of LCJ Maree SC, Mafikeng Transkei in terms of which lecturers were allowed to practise on a part-time basis. Thus in 1978, Don Thompson, Birth and name (Judge-President of the High Court of Bophuthatswana), F Kgomo (Judge Brian Leslie, Joe Renene and Selwyn In an old dilapidated minute book, the President of Northern Cape High Court) Miller (presently the Acting Judge following is to be found on the first and Nkabinde, Leeuw and Chulu President of the Transkei Division) all page: 'Ons, die ondergetekendes, stig (deceased) Uudges of the High Court of became members of the Society. hiermee 'n organisasie wat bekend sal Bophuthatswana). A number of our staan as die Balie van Advokate van The membership of the Society grew members have acted as judges in various Bophuthatswana, ook bekend as die steadily during the 1980s. New members divisions and Lever SC has also acted in Balie van Bophuthatswana. Die grond included Tholie Madala (a justice of the the High Court of Botswana. Our mem wet van die Vereniging is hierby aange Constitutional Court from its inception), bers have chaired various commissions heg as Bylae A.' The 'stigtingsakte' as Peter Rowan, Peter Barratt, Joe Miso, during the period when commissions of they called it, was signed by Advocates enquiries were fashionable. Vic Vakalisa (upon his return), Digby JJ Rossouw, TBR Kgalegi and LAYJ Koyana, Nona Goso, Sindi Majokweni, Thomas on 17 March 1981 at Mafikeng. -

The Struggle for the Rule of Law in South Africa

NYLS Law Review Vols. 22-63 (1976-2019) Volume 60 Issue 1 Twenty Years of South African Constitutionalism: Constitutional Rights, Article 5 Judicial Independence and the Transition to Democracy January 2016 The Struggle for the Rule of Law in South Africa STEPHEN ELLMANN Martin Professor of Law at New York Law School Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.nyls.edu/nyls_law_review Part of the Constitutional Law Commons Recommended Citation STEPHEN ELLMANN, The Struggle for the Rule of Law in South Africa, 60 N.Y.L. SCH. L. REV. (2015-2016). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@NYLS. It has been accepted for inclusion in NYLS Law Review by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@NYLS. NEW YORK LAW SCHOOL LAW REVIEW VOLUME 60 | 2015/16 VOLUME 60 | 2015/16 Stephen Ellmann The Struggle for the Rule of Law in South Africa 60 N.Y.L. Sch. L. Rev. 57 (2015–2016) ABOUT THE AUTHOR: Stephen Ellmann is Martin Professor of Law at New York Law School. The author thanks the other presenters, commentators, and attenders of the “Courts Against Corruption” panel, on November 16, 2014, for their insights. www.nylslawreview.com 57 THE STRUGGLE FOR THE RULE OF LAW IN SOUTH AFRICA NEW YORK LAW SCHOOL LAW REVIEW VOLUME 60 | 2015/16 I. INTRODUCTION The blight of apartheid was partly its horrendous discrimination, but also its lawlessness. South Africa was lawless in the bluntest sense, as its rulers maintained their power with the help of death squads and torturers.1 But it was also lawless, or at least unlawful, in a broader and more pervasive way: the rule of law did not hold in South Africa. -

The Judiciary As a Site of the Struggle for Political Power: a South African Perspective

The judiciary as a site of the struggle for political power: A South African perspective Freddy Mnyongani: [email protected] Department of Jurisprudence, University of South Africa (UNISA) 1. Introduction In any system of government, the judiciary occupies a vulnerable position. While it is itself vulnerable to domination by the ruling party, the judiciary must at all times try to be independent as it executes its task of protecting the weak and vulnerable of any society. History has however shown that in most African countries, the judiciary has on a number of occasions succumbed to the domination of the ruling power. The struggle to stay in power by the ruling elite is waged, among others, in the courts where laws are interpreted and applied by judges who see their role as the maintenance of the status quo. To date, a typical biography of a post-independence liberation leader turned president would make reference to a time spent in jail during the struggle for liberation.1 In the post-independence Sub-Saharan Africa, the situation regarding the role of the judiciary has not changed much. The imprisonment of opposition leaders, especially closer to elections continues to be a common occurrence. If not that, potential opponents are subjected to charges that are nothing but a display of power and might. An additional factor relates to the disputes surrounding election results, which inevitably end up in court. The role of the judiciary in mediating these disputes, which are highly political in nature, becomes crucial. As the tension heats up, the debate regarding the appointment of judges, their ideological background and their independence or lack thereof, become fodder for the media. -

Do Women on South Africa's Courts Make a Difference?

Do Women on South Africa’s Courts Make a Difference? Do Women on South Africa’s Courts Make a Difference? *By Ruth B. Cowan Research assistance provided by Colleen Normile Women’s presence on the bench in South Africa began in 1994 with the end of apartheid. As Justice Yvonne Mokgoro observes in the documentary Courting Justice, during the hundreds of preceding years “ I guess there was no thought that women could also serve.” More accurately, what kept women off the bench were the thoughts that women , unsuited by nature, could never serve. The post apartheid Constitution, setting forth a human rights- based constitutional democracy, dismissed these notions and mandated the consideration of women when making judicial appointments. The appointments were to be made to what was now to be an independent judiciary. The apartheid judiciary had not been independent—its charge was to assure the validation of apartheid’s legislation, executive regulations and official actions. Yet, these courts were to be retained, as were the judges and court personnel whose record was hostile to the very human rights which the judiciary was now charged to protect. The Constitution did create one new court ; i.e., the Constitutional Court . It was charged with and limited to considering cases in which constitutional issues were raised. Given the continued engagement of the apartheid judges --all but two of whom were white males and almost all of whom were energetic in support of apartheid’s oppressive and repressive laws and brutal actions, the transformation of the judiciary by race and gender was and continues to be verbally embraced as a high priority.