Expanding Meaningful Learning Abroad Opportunities for All Students

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Trinity Tripod, 2019-09-10

The -Established 1904- rinity ripod T T Volume CXV “Scribere Aude!” Tuesday, September 10, 2019 Number II Campus Students Taken Off Trinity Ranks #46 Monday saw the announcement of the 2020 US News Renovations Housing Waitlist and World Report College Rankings. Trinity retained JAY PARK ’22 its position at #46 in the National Liberal Arts College KAT NAMON ’22 permit a higher number of NEWS EDITOR students to live off cam- rankings. Trinity also recently ranked #87 in overall NEWS EDITOR colleges and universities in The Wall Street Journal. Triniy underwent pus this academic year. Trinity’s housing lot- Director of Residential page a series of renova- tions on campus, tery annually leaves a Life Susan Salisbury dis- particularly in number of students with- cussed the change with the four year graduation rate Mather. out housing, due to factors Tripod, noting that “Ev- 78% which include shifting cir- erybody got housed, there cumstances, dorm avail- were a few students, not 4 ability, and low lottery very many, that came back avg. starting salary numbers. Last semester, and said they wanted to live $55,400 Trin Fits: due to the closing of the together, and because we Boardwalk and Park Place couldn’t accommodate them fall 2018 acceptance rate dormitories, 50 students during the time of the lot- 34% Fashion were left on the waitlist to tery, the Dean of Students receive their housing as- office permitted us to allow MICKEY CORREA ’20 signments. In past years, them to live off campus.” Whitman College (WA) COLUMNIST as many as 100 students Typically, the Dean Tied Furman University (SC) have been on the waitlist, of Students Office im- Dickinson College (PA) page The Tripod brings however, despite these poses a 175-student lim- Depauw University (IN) back its fashion high numbers, students it on those released from with: Connecticut College (CT) column, high- always end up with a the College’s on-campus Berea College (KY) lighting Bantams housing assignment by the housing requirement. -

Below Is a Sampling of the Nearly 500 Colleges, Universities, and Service Academies to Which Our Students Have Been Accepted Over the Past Four Years

Below is a sampling of the nearly 500 colleges, universities, and service academies to which our students have been accepted over the past four years. Allegheny College Connecticut College King’s College London American University Cornell University Lafayette College American University of Paris Dartmouth College Lehigh University Amherst College Davidson College Loyola Marymount University Arizona State University Denison University Loyola University Maryland Auburn University DePaul University Macalester College Babson College Dickinson College Marist College Bard College Drew University Marquette University Barnard College Drexel University Maryland Institute College of Art Bates College Duke University McDaniel College Baylor University Eckerd College McGill University Bentley University Elon University Miami University, Oxford Binghamton University Emerson College Michigan State University Boston College Emory University Middlebury College Boston University Fairfield University Morehouse College Bowdoin College Florida State University Mount Holyoke College Brandeis University Fordham University Mount St. Mary’s University Brown University Franklin & Marshall College Muhlenberg College Bucknell University Furman University New School, The California Institute of Technology George Mason University New York University California Polytechnic State University George Washington University North Carolina State University Carleton College Georgetown University Northeastern University Carnegie Mellon University Georgia Institute of Technology -

Things Get Heated in the Kitchen: Sodexo Controversy Is Fueled by Moravian Students by Katie Makoski Reporter

t he Volume CXXIV, Issue NumberCOMENIAN 6 Moravian College’s Student Newspaper Thursday, March 3, 2011 Things Get Heated in the Kitchen: Sodexo Controversy is Fueled by Moravian Students By Katie Makoski Reporter Recently, miscommunications among students and staff have led to much confusion and controversy surrounding Moravian’s dining services. The tension finally came to a boil on February 10, when junior Armando Chapelliquen and adjunct political science professor Faramarz Farbod hosted a formal discussion concerning the allegations that Sodexo, Moravian’s food supplier, is guilty of human rights violations. Immediately upon hearing this, Don, a worker in the Marketplace, avidly defended his boss. He asserted that in the thirty-five years that he has worked for Sodexo, he has never had a problem with the company. He further stated that if Moravian were to cut ties with Sodexo there would be a chance that he and some of his coworkers would lose their jobs. photo courtesy of www.seiu21la.org Members of the dining services staff attended the discussion in order to voice these concerns. Another cause for confusion was the petition expressing dissatisfaction with Moravian’s dining services that was signed by four hundred students last semester. The petition, which called for an end to mandatory meal plans for freshman and residents of certain dorms, more options for people with dietary restrictions, and more respect for the workers, was unrelated to the discussion. In fact, these issues are not the fault of the Sodexo Sodexo is the twenty-first largest corporation in the years and has pledged to continue to donate millions of Corporation—it is Moravian College that determines world, with 380,000 workers in eighty different countries. -

Founded by Abolitionists, Funded by Slavery: Past and Present Manifestations of Bates College’S Founding Paradox

Bates College SCARAB Honors Theses Capstone Projects 5-2020 Founded by Abolitionists, Funded by Slavery: Past and Present Manifestations of Bates College’s Founding Paradox Emma Soler Bates College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scarab.bates.edu/honorstheses Recommended Citation Soler, Emma, "Founded by Abolitionists, Funded by Slavery: Past and Present Manifestations of Bates College’s Founding Paradox" (2020). Honors Theses. 321. https://scarab.bates.edu/honorstheses/321 This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Capstone Projects at SCARAB. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of SCARAB. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Founded by Abolitionists, Funded by Slavery: Past and Present Manifestations of Bates College’s Founding Paradox An Honors Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the American Studies Program Bates College In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Arts By Emma Soler Lewiston, Maine April 1, 2020 1 Acknowledgements Thank you to Joe, who inspired my interest in this topic, believed in me for the last three years, and dedicated more time and energy to this thesis than I ever could have asked for. Thank you to Ursula, who through this research became a partner and friend. Thank you to Perla, Nell, Annabel and Ke’ala, all of whom made significant contributions to this work. Thank you to the other professors who have most shaped my worldview over the past four years: Christopher Petrella, Yannick Marshall, David Cummiskey, Sonja Pieck, Erica Rand, Sue Houchins, Andrew Baker, and Anelise Shrout. -

College Counseling Program

College Counseling Program The Oregon Episcopal School college counseling team works closely with students as they search for colleges in which they will thrive. Encouraging them to take ownership of the experience, we combine individualized advice with programs and resources designed to help students—and their families—navigate the search and application phases in a thoughtful manner. Throughout high school, we provide guidance, perspective, and timely information intended to demystify the process and encourage wise choices. Underpinning our approach is a desire to have students make the most of their high school experience in a healthy, balanced manner. COLLEGE NIGHTS FOR PARENTS We offer workshops for parents, tailored by grade level, to learn about the college search process, and a presentation on financing college. For more information, visit: COLLEGE ATTENDANCE oes.edu/college Graduates of OES attend an impressive array of colleges throughout the United States and internationally. OES has an excellent, well-established reputation with colleges across the country and hosts visits from over 130 college representatives in a typical year. Colleges Attended Public vs. Private Public 29% 71% Private Non U.S.: 4% Admissions 6300 SW Nicol Road | Portland, OR 97223 | 503-768-3115 | oes.edu/admissions OES STUDENTS FROM THE CLASSES OF 2020 AND 2021 WERE ACCEPTED TO THE FOLLOWING COLLEGES Acadia University Elon University Pomona College University of Chicago Alfred University Emerson College Portland State University University of Colorado, -

Colby College Catalogue 1967 - 1968

Colby College Digital Commons @ Colby Colby Catalogues Colby College Archives 1967 Colby College Catalogue 1967 - 1968 Colby College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.colby.edu/catalogs Part of the Curriculum and Instruction Commons, and the Higher Education Commons Recommended Citation Colby College, "Colby College Catalogue 1967 - 1968" (1967). Colby Catalogues. 80. https://digitalcommons.colby.edu/catalogs/80 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Colby College Archives at Digital Commons @ Colby. It has been accepted for inclusion in Colby Catalogues by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Colby. I COLBY COLLEGE BULLETIN 'A TERVILLE, MA INE•FOUNDED IN 1813 •ANNUAL CA TALOGUE ISSUE• SEPTEMBER, 1967 2 I COLBY COLLEGE: INQUIRIES Inquiries to the college should be directed as follows: ADMISSION HARRY R. CARROLL, Dean of Admissions ADULT EDUCATION AND JOHN B. SIMPSON, Director of Summer and Special Programs SUMMER PROGRAMS FINANCIAL ARTHUR W. SEEPE, Treasurer HEALTH AND CARL E. NELSON, Director of Health Services MEDICAL CARE HOUSING FRANCES F. SEAMAN (MRs.), Dean of Students PLACEMENT EARLE A. McKEEN, Director of Career Planning and Placement RECORDS AND TRANSCRIPTS GEORGE L. CoLEMAN, Registrar SCHOLARSHIPS AND CHARLES F . H1cKox, JR., Director of Financial Aid and EMPLOYMENT Coordinator of Government-Supported Programs SUMMER SCHOOL OF Director of the Summer School of Languages LANGUAGES ' VETERANS AFFAIRS GEORGE L. COLEMAN, Registrar A booklet, ABOUT COLBY, with illustrative material, has been prepared for prospective students and may be obtained from the dean of admissions. College address: Colby College, Waterville, Maine 04901. SERIES 66 The COLBY COLLEGE BULLETIN is published five times yearly, in: May, June, September, December, and March. -

College Fair RSVP 2019

College & Career Fair Representatives (as of 9/13/19) Texas Colleges & Universities: Out of State Colleges & Universities Continued: Art, Culinary, Design, Fashion and Film: Abilene Christian University* Abilene,TX Juniata College* Huntingdon, PA Columbus College of Art & Design Columbus, Ohio Angelo State University San Angelo, TX Kansas State University Manhattan KS Auguste Escoffier School of Culinary Arts Austin, TX Austin College* Sherman, TX Lehigh University* Bethlehem PA FIDM Los Angeles, CA Austin Community College Austin, TX Louisiana State University Baton Rouge, LA Full Sail University Winter Park, FL Baylor University* Waco, TX Loyola University New Orleans* New Orleans, LA New York Film Academy New York, NY Dallas Baptist University* Dallas, TX Miami University Oxford, Ohio Hardin-Simmons University* Abilene, TX Michigan State University East Lansing, MI International Colleges & Universities: Howard Payne University Brownwood, TX Millsaps College* Jackson, MS IE University, Spain Madrid/Segovia, Spain Our Lady of the Lake University* San Antonio, TX Mississippi State University Starkville, MS Nottingham Trent University Nottingham, England Schreiner University* Kerrville, TX Missouri University of Science & Technology Rolla, MO University of St Andrews St Andrews, Scotland Southern Methodist University* Dallas, TX Northeastern University Boston, MA University of Strathclyde Scotland, UK Southwestern University* Georgetown, TX Northwestern University* Evanston, IL Franklin University Switzerland Lugano, Switzerland St. Edward's -

Orientation 2020 Md1

NEW STUDENT ORIENTATION 2020 MD1 June 29 – 30 Office of Admissions and Student Affairs NEW STUDENT ORIENTATION 2020 MD1 Dear Morehouse School of Medicine Student: Our school is graced by an overwhelming number of exceptionally well-qualified applicants. You are in good company, and I am delighted to help you begin your journey into the remark- able profession of medicine. Professional school study is a time of exploration and immersion in your desired specialty. It is a time for the free exchange of ideas, acquisition of new skills, and creation of knowledge. It is a time when faculty will change from being your teachers to being mentors and colleagues. Morehouse School of Medicine was founded in 1975 as the Medical Education Program at Morehouse College. In 1981, Morehouse School of Medicine became an independently chartered institution and the first established at a Historically Black College and University in the 20th century. Our focus on primary care and addressing the needs of the underserved is critical to improving overall health care. During the course of my career, I have had the privilege to work in several other major health sciences centers, and I believe our faculty is second to none. Our faculty and staff are commit- ted to exceptional teaching, research, and patient care. We will never lose sight of the respon- sibility to guide, support, and teach. Morehouse School of Medicine has graduated many med- ical students over the years, and we remain the leading educator of primary care physicians in the United States. Our medical school is inextricably linked to our principal teaching hospital, Grady Memorial Hospital, and several affiliates: The Atlanta VA, WellStar Atlanta Medical Center, and Chil- dren’s Healthcare of Atlanta. -

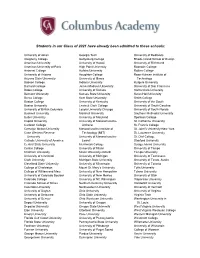

Students in Our Class of 2021 Have Already Been Admitted to These Schools

Students in our Class of 2021 have already been admitted to these schools: University of Akron Georgia Tech University of Redlands Allegheny College Gettysburg College Rhode Island School of Design American University University of Hawaii University of Richmond American University of Paris High Point University Roanoke College Amherst College Hofstra University Rollins College University of Arizona Houghton College Rose-Hulman Institute of Arizona State University University of Illinois Technology Babson College Indiana University Rutgers University Barnard College James Madison University University of San Francisco Bates College University of Kansas Santa Clara University Belmont University Kansas State University Seton Hall University Berea College Kent State University Smith College Boston College University of Kentucky University of the South Boston University Lewis & Clark College University of South Carolina University of British Columbia Loyola University Chicago University of South Florida Bucknell University Marshall University Southern Methodist University Butler University University of Maryland Spelman College Capital University University of Massachusetts- St. Catherine University Carleton College Amherst St. Francis College Carnegie Mellon University Massachusetts Institute of St. John’s University-New York Case Western Reserve Technology (MIT) St. Lawrence University University University of Massachusetts- St. Olaf College Catholic University of America Lowell Stanford University Central State University Merrimack College -

2021-2022 Colby College Catalogue

2021-2022 Colby College Catalogue Colby College 1 2021-2022 Catalogue ABOUT COLBY Founded in 1813, Colby College is the 12th oldest liberal arts college in the United States. Distinctive in its offerings, Colby provides an intimate, undergraduate-focused learning environment with a breadth of programs presenting students and faculty with unparalleled opportunities. A vibrant and fully integrated academic, residential, and cocurricular experience is sustained by a diverse and supportive community. Located in Waterville, Maine, Colby is a global institution with students representing nearly every U.S. state and approximately 70 countries. Colby’s model provides the scale and impact of larger universities coupled with intensive learning in a community committed to scholarship and discovery, multidisciplinary approaches to integrated learning, study in the liberal arts, and leading-edge programs addressing the world’s most complex challenges. Its network of partnerships with prestigious cultural, research, medical, and business institutions extends educational and scholarly collaborations, providing students with unmatched experiences leading to postgraduate success. The College’s wide variety of programs and labs provides students and the community access to unique experiences: the Colby College Museum of Art, the finest college art museum in the country, and the Lunder Institute for American Art have made the College a nationally and internationally recognized center for art scholarship; DavisConnects prepares students for lifelong success by combining a forward- thinking liberal arts education with extensive internship, research, and global opportunities for all students regardless of their personal networks and financial circumstances; and the 350,000-square-foot Harold Alfond Athletics and Recreation Center, opened in 2020, is the most advanced and comprehensive NCAA D-III facility in the country. -

College/University Visit Clusters

COLLEGE/UNIVERSITY VISIT CLUSTERS The groupings of colleges and universities below are by no means exhaustive; these ideas are meant to serve as good starting points when beginning a college search. Happy travels! BOSTON/RHODE ISLAND AREA Large: Boston University University of Massachusetts at Boston Northeastern University Medium: Bentley University (business focus) Boston College Brandeis University Brown University Bryant College (business focus) Harvard University Massachusetts Institute of Technology Providence College University of Massachusetts at Lowell University of Rhode Island Suffolk University Small: Babson College (business focus) Emerson College Olin College Rhode Island School of Design (art school) Salve Regina University Simmons College (all women) Tufts University Wellesley College (all women) Wheaton College CENTRAL/WESTERN MASSACHUSETTS Large: University of Massachusetts at Amherst/Lowell Medium: College of the Holy Cross Worcester Polytechnic Institute Small: Amherst College Clark University Hampshire College Mount Holyoke College (all women) Smith College (all women) Westfield State University Williams College CONNECTICUT Large: University of Connecticut Medium: Fairfield University Quinnipiac University Yale University Small: Connecticut College Trinity College Wesleyan University NORTHERN NEW ENGLAND Large: University of New Hampshire University of Vermont Medium: Dartmouth College Middlebury College Small: Bates College Bennington College Bowdoin College Colby College College of the Atlantic Saint Anselm College -

Trinity School Upper School Profile of Durham and Chapel Hill Class of 2020

Trinity School Upper School Profile of Durham and Chapel Hill Class of 2020 Mission T he mission of Trinity School is to educate students in transitional kindergarten to grade twelve within the framework of Christian faith and conviction—teaching the classical tools of learning; providing a rich yet unhurried curriculum; and communicating truth, goodness, and beauty. History Trinity was founded in 1995 by parents seeking a Christian school with an excellent college preparatory program that integrates faith and learning. Trinity’s Upper School was established in the fall of 2006, with 16 students graduating in the Class of 2010. Today, 194 students are enrolled in the Upper School, including 51 seniors in the Class of 2020. Community Trinity’s families come from across the greater Durham and Chapel Hill area and include research scientists, engineers, and doctors; university deans and professors; pastors and church elders; directors of nonprofits, community volunteers, and mission trip organizers; artists and writers; venture capitalists, entrepreneurs, and CEOs; and stay-at-home parents. Upper 532 students attend Trinity grades TK–12: 241 in LS (TK–6), 97 in MS (7–8), and 194 in US (9–12). More School than 70 Christian churches are represented among the student body, as well as other religious and secular backgrounds. ■ 36 faculty ■ Average class size of 14 students ■ 81% hold advanced degrees, including 3 PhDs ■ 30% students of color ■ 8:1 student-teacher ratio ■ 38% of students receive tuition assistance Academic Deep, inquiry-based study. Trinity’s Upper School engages students in a rich liberal arts curriculum that Program values depth and understanding, Socratic discussion, inquiry and self-discovery, self-reflection, eloquent expression, critical and creative thinking, and the classical tools of learning.