Filed an Emergency Application

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Organization Exempt from Rnr Ome T^"

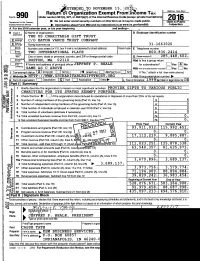

XTENDEDG^TO NOVEMBER 15,1-201 Return'o4- Organization Exempt From rnr ome T^". OMB No 1545-0047 Form 990 Under section 501(c), 527, or 4947(a)(1) of the Internal Revenue Code (except private foundat Do not enter social security numbers on this form as it may be made public. Department of the Treasury ► Internal Revenue Service Pop, Information about Form 990 and its instructions is at www.1rs. gov/form990. A For the 2016 calendar year or tax year beginning and ending= B Check it C Name of organization D Employer identification number applicable THE US CHARITABLE GIFT TRUST Ochanges C/O EATON VANCE TRUST COMPANY Naem Ochange Dom business as 31-1663020 Initial return Number and street (or P.O. box if mail is not delivered to street address) Room/suite E Telephone number lFinal return/ TWO INTERNATIONAL PLACE 800-836-2414 aed^n City or town, state or province, country, and ZIP or foreign postal code G Gross receipts $ 285,448,602. = Amended return BOSTON, MA 02110 H(a) Is this a group return Lttionlica- F Name and address of principal officer JEFFREY P. BEALE for subordinates? E]Yes ® No pending SAME AS C ABOVE H(b) Are all subordinates included70 Yes Li No I Tax-exempt status X 501(c)(3) 501(6) ( )A (insert no.) L-J 4947(a)( or 77527 If "No," attach a list (see instructions) HTTP : / /WWW. USCHARITABLEGIFTTRUST. ORG J Website: ► K Form of organization: Corporation X Trust L_J Association L_J Year of State of leaal domicile: DE Part I Summary CD 1 Briefly describe the organization's mission or most significant activities- PROVIDE GIFTS TO VARIOUS PUBLIC a CHARITIES FOR ITS STATED EXEMPT PURPOSE. -

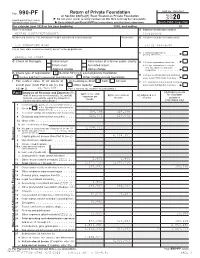

2020 Or Tax Year Beginning , 2020, and Ending , 20 Name of Foundation a Employer Identification Number MCLEAN CONTRIBUTIONSHIP 23-6396940 Number and Street (Or P.O

OMB No. 1545-0047 Form 990-PF Return of Private Foundation or Section 4947(a)(1) Trust Treated as Private Foundation Do not enter social security numbers on this form as it may be made public. Department of the Treasury Internal Revenue Service Go to www.irs.gov/Form990PF for instructions and the latest information. Open to Public Inspection For calendar year 2020 or tax year beginning , 2020, and ending , 20 Name of foundation A Employer identification number MCLEAN CONTRIBUTIONSHIP 23-6396940 Number and street (or P.O. box number if mail is not delivered to street address) Room/suite B Telephone number (see instructions) 230 SUGARTOWN ROAD (610) 989-8090 City or town, state or province, country, and ZIP or foreign postal code C If exemption application is pending, check here WAYNE, PA 19087 G Check all that apply: Initial return Initial return of a former public charity D 1. Foreign organizations, check here Final return Amended return 2. Foreign organizations meeting the Address change Name change 85% test, check here and attach computation H Check type of organization:X Section 501(c)(3) exempt private foundation E If private foundation status was terminated Section 4947(a)(1) nonexempt charitable trust Other taxable private foundation under section 507(b)(1)(A), check here X I Fair market value of all assets at J Accounting method: Cash Accrual F If the foundation is in a 60-month termination end of year (from Part II, col. (c), line Other (specify) under section 507(b)(1)(B), check here 16) $ 68,764,997. -

Other As Well (Not Just with Teva)

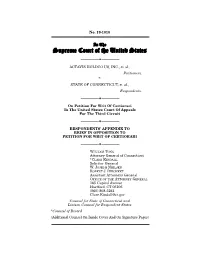

No. 19-1010 ================================================================================================================ In The Supreme Court of the United States --------------------------------- ♦ --------------------------------- ACTAVIS HOLDCO US, INC., et al., Petitioners, v. STATE OF CONNECTICUT, et al., Respondents. --------------------------------- ♦ --------------------------------- On Petition For Writ Of Certiorari To The United States Court Of Appeals For The Third Circuit --------------------------------- ♦ --------------------------------- RESPONDENTS’ APPENDIX TO BRIEF IN OPPOSITION TO PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI --------------------------------- ♦ --------------------------------- WILLIAM TONG Attorney General of Connecticut *CLARE KINDALL Solicitor General W. J OSEPH NIELSEN ROBERT J. DEICHERT Assistant Attorneys General OFFICE OF THE ATTORNEY GENERAL 165 Capitol Avenue Hartford, CT 06106 (860) 808-5261 [email protected] Counsel for State of Connecticut and Liaison Counsel for Respondent States *Counsel of Record (Additional Counsel On Inside Cover And On Signature Pages) ================================================================================================================ ROBERTA D. LIEBENBERG JEFFREY S. ISTVAN FINE, KAPLAN AND BLACK, R.P.C. One South Broad Street, 23rd Floor Philadelphia, PA 19107 (215) 567-6565 rliebenberg@finekaplan.com Lead Counsel for the End-Payer Plaintiffs DIANNE M. NAST NASTLAW LLC 1101 Market Street, Suite 2801 Philadelphia, PA 19107 (215) 923-9300 [email protected] Lead -

85737NCJRS.Pdf

If you have issues viewing or accessing this file contact us at NCJRS.gov. / A !?~ liD 1j ~ \ ~~~~~~~ , ERNME , 'l , --~ --~--- ---- ----------------- -------------------------:;~ .. ---"'----,-.---"-" ,-,--------~-- ..--------- Consumer's Resource Handbook PUblished by Virginia H. Knauer Special Assistant to the President and Director U.S. Office of Consumer Affairs Prepared by: 1 ;r.' .::;' Anna Gen~' BarneN C -\1 l'E3l 'e:'::i Dan Rumelt Anne Turner Chapman td) JF~ i;;J), Juanita Yates Roger Goldblatt g;tj 1~ i~ iA~H1.f€fJnt~fl.19N s " Evelyn Ar,pstrong Nellie lfegans [;::;, Elva Aw-e-' .. Cathy' Floyd Betty Casey Barbara Johnson Daisy B. Cherry Maggie Johnson Honest transactions in a free market between Marion Q. Ciaccio Frank Marvin buyers and sellers are at the core of individual, Christine Contee Constance Parham community, and national economic growth. Joe Dawson Howard Seltzer Bob Steeves In the final analysis, an effective and efficient I' system of commerce depends on an informed :,; and educated public. An excerpt from President Reagan's Proclama· tion of National Consumers Week, Ap~~jl 25- May 1, 1982. September 1982 U.S. Department of Justice National Institute of Justice This docl.ornent has been reproduced exactly as recei~e? from the person or organization orlqinating it. Points of view or opInions stat~d in tt;>is document are tho'se of the authors and do not nec~ssanly represent the official position or policies of the National Institute of Justice. Permission to reproduce this ~ed material has been \' granted by ~bl;c Domajn II.S. Office of Consumer Affairs Additional free single copies of the Consumer's Resource Handbook may be obtained by writing to Handbook, , to the National Criminal Justice Reference Service (NCJRS). -

State of Center City Philadelphia 2021

STATE OF CENTER CITY PHILADELPHIA 2021 Restoring | Returning | Reanimating Contents Introduction 1 Office 12 Health Care & Higher Education 18 Conventions, Tourism & Hotels 23 Arts & Culture 27 Retail 30 Employment 37 Transportation & Access 47 Downtown Living 53 Developments 62 Acknowledgements 64 Center City District & Central Philadelphia Development Corporation CENTERCITYPHILA.ORG Chapter Name| 1 Reanimating the City District | Center Center of the City Park Dilworth The global pandemic, local stay-at-home mandates and civil boarded-up storefronts and installed new artwork on many. We unrest created extraordinary challenges for all cities. In Center commissioned 200 decorative banners created by Philadelphia City, pedestrian volumes initially plummeted by 72%, as office artists. Our landscape teams planted street trees, filled park workers, hotel guests, regional shoppers, students, theater and flowerbeds with tens of thousands of bulbs and upgraded street restaurant patrons disappeared. At night, streets were devoid of lighting. We continued to provide fee-for-service cleaning for five cars, sidewalks were empty. From the very start in March 2020, adjacent residential neighborhoods. we had all of our on-street and park employees designated To enhance safety, we deployed new bike patrols and security “essential workers.” The central lesson from the Center City vans in afternoons and seven evenings per week, supplement- District’s founding 30 years ago suddenly had renewed reso- ing the role of our Community Service Representatives (CSRs). nance: the revival of economic activity and vitality depends upon In 2020, CSRs had more than 177,000 sustained conversations confidence in a public environment that is clean, safe with pedestrians seeking directions, responding to inquiries and attractive. -

ADDRESS: 1106-14 SPRING GARDEN ST Name of Resource: Woodward-Wanger Co

ADDRESS: 1106-14 SPRING GARDEN ST Name of Resource: Woodward-Wanger Co. Proposed Action: Rescind Designation and then Reconsider Nomination Property Owner: Mapleville, LLC, Stella and Nga Wong Applicant: Matt McClure, Esq., Ballard Spahr Individual Designation: 3/9/2018 District Designation: None Staff Contact: Jon Farnham, [email protected] OVERVIEW: This request asks the Historical Commission to rescind the individual designation of the property at 1106-14 Spring Garden Street and then remand the nomination to the Committee on Historic Designation for an entirely new review in which the property owner can participate. The rescission request contends that the property owner was not notified of the consideration of the nomination by the Committee on Historic Designation and the Historical Commission that led to the designation on 9 March 2018 and, therefore, did not have an opportunity to participate in reviews. The request asserts that the Historical Commission sent the first and final notice letters for the property owner to the wrong address because the City failed to correctly update its property tax records. The other set of notice letters, those to the property, were sent to a vacant building, where mail could not be received. Documents included with the rescission request seem to indicate that the claim is correct. It appears that the Historical Commission sent the first and final notice letters for the property owner to an outdated address. The owner did not participate in two public meetings at which the nomination was reviewed. The request indicates that the owner did not learn of the designation until 2020, when applying for a permit from the Department of Licenses & Inspections. -

990-PF Return of Private Foundation

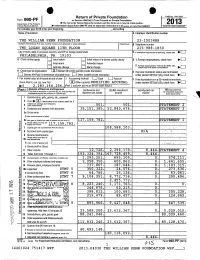

Return of Private Foundation OMB No 1545-0052 Form 990-PF or Section 4947(a)(1) Trust Treated as Private Foundation Department of the Treasury 10- Do not enter Social Security numbers on this form as it may be made public. 2013 Internal Revenue Service 110 Information about Form 990-PF and its separate instructions is at wvAv irs oov/form For calendar year 2013 or tax year beginning , and ending Name of foundation A Employer identification number THE WILLIAM PENN FOUNDATION 23-1503488 Number and street (or P O box number if mail is not delivered to street address ) Room/suite B Telephone number TWO LOGAN SQUARE 11TH FLOOR 215-988-1830 City or town, state or province, country, and ZIP or foreign postal code C If exemption application is pending , check here ► PHILADELPHIA, PA 19103 G Check all that apply: L_J Initial return L_J Initial return of a former public charity D 1. Foreign organizations , check here EDFinal return Amended return 2. Foreign organizations meeting the 85% test, Address chan g e Name change check here and attach computation H Check type of organization: X Section 501 (c)(3) exempt private foundation E If private foundation status was terminated = Section 4947(a)( 1) nonexempt charitable trust 0 Other taxable private foundation under section 507(b)(1)(A), check here ► Fair market value of all assets at end of year J Accounting method : L_J Cash L_J Accrual F If the foundation is in a 60-month termination (from Part ll, col (c), line 16) OX Other (specify) MODIFIED ACCRUAL under section 507(b)(1)(B), check here ► $ 2 , 2 8 3 ,16 4 , 2 5 6 . -

IN the SUPREME COURT of PENNSYLVANIA No. the PENNSYLVANIA GAMING CONTROL BOARD Petitioner, V. CITY COUNCIL of PHILADELPHIA; PATR

IN THE SUPREME COURT OF PENNSYLVANIA No. THE PENNSYLVANIA GAMING CONTROL BOARD Petitioner, v. CITY COUNCIL OF PHILADELPHIA; PATRICIA RAFFERTY, in her capacity as Chief Clerk of City Council of Philadelphia; PHILADELPHIA COUNTY BOARD OF ELECTIONS; and THE HONORABLE NELSON DIAZ, THE HONORABLE PAUL JAFFE, and THE HONORABLE GENE COHEN, acting City Commissioners, in their official capacity as the Philadelphia County Board of Elections, Respondents. _________________________________________ EMERGENCY PETITION OF THE PENNSYLVANIA GAMING CONTROL BOARD IN THE NATURE OF A COMPLAINT FOR DECLARATORY JUDGMENT _________________________________________ Lawrence T. Hoyle, Jr. (PA ID No. 02926) Arlene Fickler (PA ID No. 20327) Jeffrey S. Waksman (PA ID No. 79873) Hoyle, Fickler, Herschel & Mathes LLP One South Broad Street, Suite 1500 Philadelphia, PA 19107 (215) 981-5700 Frank T. Donaghue (PA ID No. 72561) R. Douglas Sherman (PA ID No. 50092) Linda S. Lloyd (PA ID No. 66720) Pennsylvania Gaming Control Board Office of Chief Counsel 303 Walnut Street, Strawberry Square Verizon Towers, 5th Floor Harrisburg, PA 17101-1825 (717) 346-8300 Attorneys for Petitioner The Pennsylvania Gaming Control Board DATED: April 5, 2007 Pursuant to Rules 3307 of the Pennsylvania Rules of Appellate Procedure, NOW COMES Petitioner, Pennsylvania Gaming Control Board (the “Board”), by and through its counsel, and alleges as follows: INTRODUCTION 1. Pursuant to the Pennsylvania Race Horse Development and Gaming Act (“Gaming Act”), 4 Pa. C.S. §§ 1101-1904, the Commonwealth has -

Case 18-19054-JNP Doc 378 Filed 07/05/18 Entered 07/05/18 17:02:10 Desc Main Document Page 1 of 26

Case 18-19054-JNP Doc 378 Filed 07/05/18 Entered 07/05/18 17:02:10 Desc Main Document Page 1 of 26 UNITED STATES BANKRUPTCY COURT DISTRICT OF NEW JERSEY Caption in Compliance with D.N.J. LBR 9004-1 PORZIO, BROMBERG & NEWMAN, P.C. 100 Southgate Parkway P.O. Box 1997 Morristown, New Jersey 07962 (973) 538-4006 (973) 538-5146 Facsimile Warren J. Martin Jr., Esq. ([email protected]) Kelly D. Curtin, Esq. ([email protected]) Rachel A. Parisi, Esq. ([email protected]) Counsel to Debtors Case No.: 18- 19054 (JNP) In Re: (Jointly Administered) Garces Restaurant Group, Inc., d/b/a Garces Group, et al.,1 Chapter: 11 Debtors. Judge: Jerrold N. Poslusny, Jr. CERTIFICATION OF SERVICE 1. I, Neidy V. Fuentes : represent the Debtors, in the above-captioned matters X am a paralegal for Warren J. Martin Jr., who is counsel to the Debtors in the above-captioned matters. am the in the above case and am representing myself. I caused the following pleadings and/or documents to be 2. On June 29, 2018 served on the parties listed in the chart below: Order: (I) Establishing Deadline and Procedure for Filing Certain Administrative Claims; and (II) Approving Form, Manner, and Sufficiency of Notice Thereof [Docket No. 361] 1 The Debtors in these cases and the last four digits of their employee identification numbers are: GRGAC1, LLC d/b/a Amada (7047); GRGAC2, LLC d/b/a Village Whiskey (7079); GRGAC3, LLC d/b/a Distrito Cantina (7109); GRGAC4, LLC (0542); Garces Restaurant Group, Inc. -

Read Our Most Recent Annual Report

DOLFINGER-McMAHON FOUNDATION Fifty-Sixth Report on Operations January 1, 2020 ─ December 31, 2020 PART I HISTORY OF THE DOLFINGER-McMAHON FOUNDATION The assets of the Dolfinger-McMahon Foundation were provided by Henry Dolfinger, who died in June 1939, and in part from his son-in-law, J. Edward McMahon, who died in July 1951. The source of a majority of those assets was the Dolfinger Dairy, which was sold by Henry Dolfinger to Abbotts Dairies. The creators of the Foundation and donors of the funds now comprising the Foundation were Mrs. J. Edward McMahon (Caroline D. McMahon), the only child of Henry Dolfinger, and Mary M. McMahon, the only child of Mrs. J. Edward McMahon. During most of their lives the families received legal counsel from Maurice Heckscher, Esquire and Sanford D. Beecher, Esquire, partners practicing law with Duane, Morris & Heckscher. By the mid 1950s, both Caroline D. McMahon and her only child Mary M. McMahon concluded that they would have no direct descendants and determined to leave large portions of their money to their lawyers, Messrs. Beecher and Heckscher. Those lawyers concluded that they could not ethically accept such legacies, having been close family advisors for many years. Both Caroline D. and Mary M. McMahon at first resisted this conclusion, but eventually became quite enthusiastic about establishing a perpetual foundation to be administered by Duane, Morris & Heckscher partners as trustees to benefit charitable purposes and memorialize to some extent the Dolfinger and McMahon names. The Trustees who have succeeded Messrs. Beecher and Heckscher note with pride the integrity they exhibited in refusing to accept substantial legacies and applaud the spirit of the goals established by these men as the original trustees of this Foundation. -

The City of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

PRELIMINARY OFFICIAL STATEMENT DATED NOVEMBER 22, 2013 NEW ISSUE: BOOK-ENTRY ONLY RATINGS: Moody’s: “MIG 1” S&P: “SP-1+” (See “Ratings” herein) In the opinion of Co-Bond Counsel, interest on the Notes is not includable in gross income for purposes of federal income taxation under existing statutes, regulations, rulings and court decisions, subject to the conditions described in “TAX MATTERS” herein. Interest on the Notes will not be an item of tax preference for purposes of the individual and corporate alternative minimum taxes; however, such interest is taken into account in computing the alternative minimum tax for certain corporations. Under the laws of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, as enacted and construed on the date hereof, the Notes are exempt from Pennsylvania personal property taxes and the interest on the Notes is exempt from Pennsylvania income tax and Pennsylvania corporate net income tax. For a more complete discussion see “TAX MATTERS” herein. $100,000,000* THE CITY OF PHILADELPHIA, PENNSYLVANIA Tax and Revenue Anticipation Notes, Series A of 2013-2014 Dated: Date of Original Delivery Due: June 30, 2014 The Tax and Revenue Anticipation Notes, Series A of 2013-2014 (the “Notes”) of The City of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania (the “City”) will be issued in registered form in denominations of $5,000 or any integral multiple thereof and will bear interest from the date of issuance to the maturity date at the annual rate set forth on the inside cover page hereof, calculated on the basis of actual days elapsed in a 365-day year. The Notes are not subject to redemption prior to maturity. -

Case 18-19054-JNP Doc 380 Filed 07/05/18 Entered 07/05/18 17:04:19 Desc Main Document Page 1 of 26

Case 18-19054-JNP Doc 380 Filed 07/05/18 Entered 07/05/18 17:04:19 Desc Main Document Page 1 of 26 UNITED STATES BANKRUPTCY COURT DISTRICT OF NEW JERSEY Caption in Compliance with D.N.J. LBR 9004-1 PORZIO, BROMBERG & NEWMAN, P.C. 100 Southgate Parkway P.O. Box 1997 Morristown, New Jersey 07962 (973) 538-4006 (973) 538-5146 Facsimile Warren J. Martin Jr., Esq. ([email protected]) Kelly D. Curtin, Esq. ([email protected]) Rachel A. Parisi, Esq. ([email protected]) Counsel to Debtors Case No.: 18- 19054 (JNP) In Re: (Jointly Administered) Garces Restaurant Group, Inc., d/b/a Garces Group, et al.,1 Chapter: 11 Debtors. Judge: Jerrold N. Poslusny, Jr. CERTIFICATION OF SERVICE 1. I, Neidy V. Fuentes : represent the Debtors, in the above-captioned matters X am a paralegal for Warren J. Martin Jr., who is counsel to the Debtors in the above-captioned matters. am the in the above case and am representing myself. I caused the following pleadings and/or documents to be 2. On June 30, 2018 served on the parties listed in the chart below: Notice of Proposed Compromise or Settlement of Controversy [Docket No. 365] 1 The Debtors in these cases and the last four digits of their employee identification numbers are: GRGAC1, LLC d/b/a Amada (7047); GRGAC2, LLC d/b/a Village Whiskey (7079); GRGAC3, LLC d/b/a Distrito Cantina (7109); GRGAC4, LLC (0542); Garces Restaurant Group, Inc. d/b/a Garces Group (0697); Latin Valley 2130, LLC; La Casa Culinary, LLC d/b/a Amada Restaurant (4127); Garces Catering 300, LLC d/b/ a Garces Catering (3791); Latin Quarter Concepts, LLC d/b/a Tinto d/b/a Village Whiskey (0067); UrbanFarm, LLC d/b/a JG Domestic (3014); GR300, LLC d/b/a Volver (0347); GRG2401, LLC (7222); GRGChubb1, LLC (8350); GRGKC1, LLC; GRGWildwood, LLC (9683); and GRGNY2, LLC (0475); GRGDC2, LLC d/b/a Latin Market (8878); GRGBookies, LLC d/b/a The Olde Bar (4779); and GRGAC5,LLC (9937).