Composing Identities: Charting Negotiations of Collaborative Composition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mavae and Tofiga

Mavae and Tofiga Spatial Exposition of the Samoan Cosmogony and Architecture Albert L. Refiti A thesis submitted to� The Auckland University of Technology �In fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Art & Design� Faculty of Design & Creative Technologies 2014 Table of Contents Table of Contents ...................................................................................................................... i Attestation of Authorship ...................................................................................................... v Acknowledgements ............................................................................................................... vi Dedication ............................................................................................................................ viii Abstract .................................................................................................................................... ix Preface ....................................................................................................................................... 1 1. Leai ni tusiga ata: There are to be no drawings ............................................................. 1 2. Tautuanaga: Rememberance and service ....................................................................... 4 Introduction .............................................................................................................................. 6 Spacing .................................................................................................................................. -

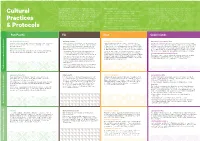

Cultural Practices & Protocols

Engagement that is meaningful is about respecting Advice may be about: By having a general understanding and knowing how to behave in these cultural practices and protocols. Pacific values common to • Formal ceremonies and knowing who and how to address situations shows Pacific communities respect and is a step in the right Cultural all Pacific Islands should always be considered when observing people and their roles in the appropriate manner direction for building good relationships. Below are a few examples any customs. However, among the different islands there are which demonstrate how practices vary from island to island. This is by • Use of island languages and translation by non-English speakers distinct differences in cultural practices, roles of family no means an exhaustive list but is merely intended to give you a basic Practices members, traditional dress and power structures. • Acknowledging and allowing time for elders to contribute introduction only. If you somehow forget everything you read here, • Taking time to observe protocols which uphold spirituality just remember to act respectfully and that it’s okay to ask if you don’t If you’re asked to attend a Pacific event or ceremony, through prayers. understand. it’s anticipated that you be accompanied and/or advised & Protocols by Pacific peoples who can help guide you. Note - A full list of basic greetings can be found at www.mpp.govt.nz - Tonga, Fiji and Samoa are the only Pacific countries that are commonly known for kava ceremony practices. Pan-Pacific Fiji Niue Cook Islands Role of spirituality in meetings Welcoming ceremony Welcoming ceremony and dance Haircutting ceremony (pakoti rouru) Pacific meetings or events usually begin and close with a prayer, and food is blessed Veiqaravi vakavanua is the traditional way to welcome an honoured guest Takalo was traditionally performed before going to war. -

Culture and Sustainable Development in the Pacific

Culture and Sustainable Development in the Pacific i ii Culture and sustainable development in the Pacific Culture and Sustainable Development in the Pacific Antony Hooper (editor) Asia Pacific Press at The Australian National University iii Co-published by ANU E Press and Asia Pacific Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] Web: http://epress.anu.edu.au Previously published by Asia Pacific Press The National Centre for Development Studies gratefully acknowledges the contribution made by the Australian Agency for International Development (AusAID) towards the publication of this series. The financial support provided by UNESCO towards the publication of this volume is also gratefully acknowledged. ISSN 0817–0444 National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Culture and sustainable development in the Pacific. ISBN 1 920942 23 8 ISBN 1 920942 22 X (Online document) 1. Sustainable development - Pacific Area. 2. Pacific Area - Social life and customs. 3. Pacific Area - Civilization. I. Hooper, Antony. 909.09823 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Series editor: Maree Tait Editor: Elizabeth St George Pagesetting: Jackie Lipsham and Matthew May Cover design: Annie Di Nallo Design Printed by DPA, Adelaide First edition © 2000 Asia Pacific Press This edition © 2005 ANU E -

Psychological Well-Being Among Latter-Day Saint Polynesian American Emerging Adults Melissa Lynn Aiono Brigham Young University

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive All Theses and Dissertations 2017-02-01 Psychological Well-Being Among Latter-day Saint Polynesian American Emerging Adults Melissa Lynn Aiono Brigham Young University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd Part of the Counseling Psychology Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Aiono, Melissa Lynn, "Psychological Well-Being Among Latter-day Saint Polynesian American Emerging Adults" (2017). All Theses and Dissertations. 6709. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd/6709 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Psychological Well-Being Among Latter-day Saint Polynesian American Emerging Adults Melissa Lynn Balan Aiono A thesis submitted to the faculty of Brigham Young University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Educational Specialist G. E. Kawika Allen, Chair Larry J. Nelson Melissa Ann Heath Department of Counseling Psychology and Special Education Brigham Young University Copyright © 2017 Melissa Lynn Balan Aiono All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT Psychological Well-Being Among Latter-day Saint Polynesian American Emerging Adults Melissa Lynn Balan Aiono Department of Counseling Psychology and Special Education, BYU Educational Specialist There is a dearth of psychological research with Polynesian populations in the United States Research on this population is needed to meet the demands of this increasingly growing population. This study aims to investigate the psychological well-being of an understudied Latter-day Saint (LDS) Polynesian American emerging adult group in order to better provide them with cultural-specific professional psychological services. -

Visitor Guide

National Park Service National Park of American Samoa U.S. Department of the Interior Paka Fa’asao o Amerika Samoa Visitor Guide Lōmiga 1 | Volume 1 A taupou, or the daughter Suesue Atumotu Explore the Islands of a village chief, performs Sā o le Lalolagi of Sacred Earth a cultural dance. alofa! E fa’afeiloa’i atu le Paka Fa’asao o ello! The National Park of American Amerika Samoa ia te oe. O se si’osi’omaga Samoa welcomes you into the heart of the To mata’aga, leo ese’ese, ma ituaiga aga HSouth Pacific, to a world of sights, sounds, ma faiga e te lē maua i isi paka fa’asao a le Iunaite and experiences that you will find in no other Setete. E tu tonu i le 2,600 maila i le itu i saute i national park in the United States. Located some sisifo o Hawai‘i, ma o lenei paka fa’asao e mamao 2,600 miles southwest of Hawai‘i, this is one of the ese ma nofoaga ‘ainā i le Iunaite Setete. most remote national park’s in the United States. E te lē maua fale ua masani ai e pei You will not find the usual facilities ona maua i isi paka fa’asao. Peita’i, a of most national parks. Instead, fa’apea o oe o se tagata su’esu’e, e te with a bit of the explorer’s spirit, maua nu’u tuufua, o la’au ma meaola you will discover secluded villages, e seāseā vaai i ai, matafaga oneonea, rare plants and animals, coral sand atoa ai mata’aga i le fogaeleele ma le beaches, and vistas of land and sea. -

Performing Selves: the Semiotics of Selfhood In

PERFORMING SELVES: THE SEMIOTICS OF SELFHOOD IN SAMOAN DANCE By DIANNA MARY GEORGINA A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN ANTHROPOLOGY WASHINGTON STATE UNIVERSITY Department of Anthropology MAY 2007 © Copyright by DIANNA MARY GEORGINA, 2007 All Rights Reserved © Copyright by DIANNA MARY GEORGINA, 2007 All Rights Reserved To the Faculty of Washington State University: The members of the Committee appointed to examine the dissertation of DIANNA MARY GEORGINA find it satisfactory and recommend that it be accepted. ___________________________________ Chair ___________________________________ ___________________________________ ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I wish to acknowledge and thank all the Samoan people who provided me with alofa , especially Cecilia and Dickie Reid and Fa’alu Iuli, choreographers Sai Stevens, Korina Chamberlin, Sandra Neria, and Taloga Tupai Drabble, and all the adolescent dancers who provided me with insights into selfhood. I would also like to thank my committee members, who helped me develop the ideas presented in this dissertation and kept me on track by asking the right questions, and who sat through several incarnations of my 56 minute documentary. Thanks, too, to all my friends and colleagues who provided me with support and inspiration, especially Millie Hill and Shawna and Adam Brown. And of course my family, who have supported me as I chase my dreams, even when they mean surviving Category 5 cyclones on tiny rocks in the South Pacific. iii PERFORMING -

A Samoan Case Study

University of Wollongong Research Online University of Wollongong Thesis Collection 1954-2016 University of Wollongong Thesis Collections 2009 Cultural transformation and modernity: a Samoan case study Deborah Colleen Gough University of Wollongong, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.uow.edu.au/theses University of Wollongong Copyright Warning You may print or download ONE copy of this document for the purpose of your own research or study. The University does not authorise you to copy, communicate or otherwise make available electronically to any other person any copyright material contained on this site. You are reminded of the following: This work is copyright. Apart from any use permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part of this work may be reproduced by any process, nor may any other exclusive right be exercised, without the permission of the author. Copyright owners are entitled to take legal action against persons who infringe their copyright. A reproduction of material that is protected by copyright may be a copyright infringement. A court may impose penalties and award damages in relation to offences and infringements relating to copyright material. Higher penalties may apply, and higher damages may be awarded, for offences and infringements involving the conversion of material into digital or electronic form. Unless otherwise indicated, the views expressed in this thesis are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of the University of Wollongong. Recommended Citation Gough, Deborah Colleen, Cultural transformation and modernity: a Samoan case study, Doctor of Philosophy thesis, Centre for Asia Pacific Social rT ansformation Studies and School of Social Sciences, Media and Communication - Faculty of Arts, University of Wollongong, 2009. -

Sāmoana As Atunuʻu: the Samoan Nation Beyond the Mālō and State-Centric Nationalism a Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Divi

SĀMOANA AS ATUNUʻU: THE SAMOAN NATION BEYOND THE MĀLŌ AND STATE-CENTRIC NATIONALISM A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAIʻI AT MĀNOA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN PACIFIC ISLANDS STUDIES May 2020 By John Falaniko Pātū Thesis Committee Terence Wesley-Smith, Chairperson Manumaua Luafata Simanu-Klutz John F. Mayer © Copyright 2020 By John Patu, Jr. ii DEDICATION This thesis is dedicated to our beloved Atunu'u, the suli of Sāmoana, past, present, and future. I specifically dedicate this thesis to my ‘āiga, my grandparents Afioga Leasi Atonio Lei’ataua and Imeleta Vāimoanalētoefeiloa’imolima’ene Taufa’asau, Afioga Pātū Pila and Lata Moimoi, to my parents Telesia Māria Atonio and John Pātū, Sr., and, and my sisters Carmelita Togi and Frances Suluama Telesia Pātū and the future of our family, Naulea-Imeleta, Vāimoana Paula, and Tava’esina Pātū. I also especially dedicate this thesis to my mentors Tōfā ‘Aumua Mata’itusi Simanu and Afioga Loau Tuiloma Dr. Luafata Simanu-Klutz, my academic mothers, whose tapua’iga and fautuaga made this entire thesis journey possible. iii A NOTE ABOUT SAMOAN ORTHOGRAPHY Samoan is a member of the Samoic branch of the Polynesan language family and a member of the larger Austronesian language family. Modern Samoan orthography ulitizes the Latin alphabet and consists of five vowels (a, e, i, o, u) and ten indigenous consonants (f, g, l, m, n, p, s, t, v, ‘) and three introduced consonants (h, k, r). The former were later inserted to accommodate the transliteration and creation of new words from other languages, primarily European. -

Cultural Transformation and Modernity: a Samoan Case Study

University of Wollongong Thesis Collections University of Wollongong Thesis Collection University of Wollongong Year 2009 Cultural transformation and modernity: a Samoan case study Deborah Colleen Gough University of Wollongong Gough, Deborah Colleen, Cultural transformation and modernity: a Samoan case study, Doctor of Philosophy thesis, Centre for Asia Pacific Social Transformation Studies and School of Social Sciences, Media and Communication - Faculty of Arts, University of Wollongong, 2009. http://ro.uow.edu.au/theses/3090 This paper is posted at Research Online. CULTURAL TRANSFORMATION AND MODERNITY: A SAMOAN CASE STUDY A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the award of the degree Doctor of Philosophy from University of Wollongong by Deborah Colleen Gough BAppSc, GradDipAdEd, MSocChgDev(Dist) Centre for Asia Pacific Social Transformation Studies and School of Social Sciences, Media & Communication 2009 CERTIFICATION I, Deborah Colleen Gough, declare that this thesis, submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the award Doctor of Philosophy in the School of Social Sciences, Media and Communication, University of Wollongong, is wholly my own work unless otherwise referenced or acknowledged. The document has not been submitted for qualifications at any other academic institution. Deborah Colleen Gough 31 August 2009 ii CONTENTS CERTIFICATION.................................................................................................... II TABLES, FIGURES & ILLUSTRATIONS.............................................................V -

Movement Characteristics of Three Samoan Dance Types

MOVEMENT CHARACTERISTICS OF THREE SAMOAN DANCE TYPES: MA'ULU'ULU, SASA AND TAUALUGA A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI'I IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN DANCE AUGUST 2004 By Jennifer Radakovich Thesis Committee: Judy Van Zile, Chairperson Betsy Fisher John Mayer © Copyright 2004 by Jennifer Radakovich III ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank: many people for providing support during my graduate studies and for making this thesis possible. First, I would especially like to thank all of the wonderful individuals with whom I worked in American Samoa for sharing their love and knowledge of Samoan dance and culture with me. Without these individuals, this thesis could not have been written. A special thank you is owed to the Tuiasosopo family for graciously taking me into their home during my fieldwork stay in Fagatogo. In addition, I would like to extend my appreciation to the Center for Pacific Island Studies for providing several tuition waivers and to the Foreign Language Area Scholarship for providing tuition waivers and monetary support throughout portions of my graduate studies. I would also like to acknowledge the Arts and Sciences Advisory Council for providing me with a monetary award that allowed me to conduct my research in American Samoa. I would also like to thank: my committee members, Judy Van Zile, Betsy Fisher and John Mayer, for their time, effort and patience during the writing process and Brian Diettrich for helpful comments on later drafts ofthe thesis. Finally, I would like to thank my family and friends for their patience and understanding. -

Form and Meaning Ofthe Polynesian Cultural Center

Highly Structured Tourist Art: Form and Meaning ofthe Polynesian Cultural Center T. D. Webb In 1993 the Polynesian Cultural Center in La'ie, Hawai'i, celebrated its thirtieth anniversary. It opened on 12 October 1963. Since then, the center has become one of Hawai'i's most popular paid attractions. It has also ignited controversy as anthropologists, curators, and even Internal Reve nue Service investigators have assailed its commercialism, arguing that it is not a center for culture, but a tourist trap. But culture or kitsch, inten tional or unwitting, the center's attractions form an unsuspected yet dis tinctive aesthetic composition. The center's overlooked aesthetic, how ever, is supplied not by any Polynesian tradition, but by Mormonism. Established by the Mormon church, the center is a forty-acre ethnic theme park. Its paved walkways wind through immaculate grounds, gift shops, refreshment stands, a 28oo-seat amphitheater, a hangar-sized res taurant, and seven landscaped settings billed as "authentic reproductions" of traditional Polynesian villages (PCC 1982, np). 1 Each village is equipped with replicas of traditional Polynesian dwellings and a staff of costumed "islanders" who demonstrate Polynesian arts, crafts, and customs daily. Most of these "villagers" are Polynesian students at Brigham Young Uni versity-Hawai'i, whose campus adjoins the center grounds and which is also owned by the Mormon church. With youthful humor, these villagers present an idyll of Polynesia that evokes popular preconceptions of the unspoiled, uncomplicated life of the islands where natives still live in grass shacks. Each evening after the villages close, the center presents its cele brated stage extravaganza of Polynesian song and dance, commonly called the "night show." At the center, tourists pay about forty dollars each to see "the islands as you always hoped they would be" (pcc 1987, np). -

Toward Historicizing Gender in Polynesia: on Vilsoni Hereniko's Woven Gods and Regional Patterns

Mageo1 Page 93 Monday, August 28, 2000 9:27 AM EDITOR’S FORUM TOWARD HISTORICIZING GENDER IN POLYNESIA: ON VILSONI HERENIKO’S WOVEN GODS AND REGIONAL PATTERNS Jeannette Marie Mageo Washington State University This article considers possible parallels between Rotuman and Samoan gender history through Vilsoni Hereniko’s book Woven Gods. Hereniko draws upon the work of Victor Turner to analyze his Rotuman data, arguing that wedding clowns reverse normative social structures. Wedding clowns are expert female practi- tioners of Rotuman joking discourse. This discourse is not only ritualized on spe- cial occasions but is also an everyday informal discourse and, I argue, is in this sense normative; it counterbalances respect discourse, which is likewise practiced in ritual (ceremonial) contexts but also in everyday polite contexts. In the Samoan precolonial sex-gender system, males and females had different discursive spe- cialties—males in politesse, females in joking. Joking was often sexual in nature and indexed practices at odds with contemporary virginal ideals for girls. Rotu- man wedding clowns may represent traces of precolonial feminine gender prac- tices that resemble precolonial Samoan practices. Further, they offer a running commentary on sex-gender colonialism. Vilsoni Hereniko takes the license to be a scholar-trickster—to docu- ment custom or to write myth as his thought processes and creativity demand. To take is also to give: Hereniko gives his readers a kind of permis- sion that I intend to take. In this essay, written in response to his work, I will be my own kind of trickster—the woman clowning at the wedding, so to speak—taking the opportunity to ask questions that Hereniko’s Woven Gods Pacific Studies, Vol.