Questions and Grey Answers on the Tate Gallery's Recovered Turners

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Art of Regeneration: the Establishment and Development of the Foundation for Art and Creative Technology, 1985–2010

The Art of Regeneration: the establishment and development of the Foundation for Art and Creative Technology, 1985–2010 Thesis submitted in accordance with the requirements of the University of Liverpool for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Jane Clayton School of Architecture, University of Liverpool August 2012 iii Abstract The Art of Regeneration: the establishment and development of the Foundation for Art and Creative Technology, 1985-2010 Jane Clayton This thesis is about change. It is about the way that art organisations have increasingly been used in the regeneration of the physical environment and the rejuvenation of local communities, and the impact that this has had on contemporary society. This historical analysis of the development of a young art organisation, the Foundation for Art and Creative Technology (FACT), which has previously not been studied in depth, provides an original contribution to knowledge with regard to art and culture, and more specifically the development of media and community art practices, in Britain. The nature of FACT’s development is assessed in the context of the political, socio- economic and cultural environment of its host city, Liverpool, and the organisation is placed within broader discourses on art practice, cultural policy, and regeneration. The questions that are addressed – of local responsibility, government funding and institutionalisation – are essential to an understanding of the role that publicly funded organisations play within the institutional framework of society, without which the analysis of the influence of the state on our cultural identity cannot be achieved. The research was conducted through the triangulation of qualitative research methods including participant observation, in-depth interviews and original archival research, and the findings have been used to build upon the foundations of the historical analysis and critical examination of existing literature in the fields of regeneration and culture, art and media, and museum theory and practice. -

British Art Studies September 2019 London, Asia, Exhibitions, Histories

British Art Studies September 2019 London, Asia, Exhibitions, Histories Edited by Hammad Nasar and Sarah Victoria Turner British Art Studies Issue 13, published 30 September 2019 London, Asia, Exhibitions, Histories Edited by Hammad Nasar and Sarah Victoria Turner Cover image: Rubber shavings made during Bettina Fung's performance of "Towards All or Nothing (In Memory of Li Yuan-chia)" at Manchester Art Gallery, 6 March 2019.. Digital image courtesy of Bettina Fung. PDF generated on 21 July 2021 Note: British Art Studies is a digital publication and intended to be experienced online and referenced digitally. PDFs are provided for ease of reading offline. Please do not reference the PDF in academic citations: we recommend the use of DOIs (digital object identifiers) provided within the online article. Theseunique alphanumeric strings identify content and provide a persistent link to a location on the internet. A DOI is guaranteed never to change, so you can use it to link permanently to electronic documents with confidence. Published by: Paul Mellon Centre 16 Bedford Square London, WC1B 3JA https://www.paul-mellon-centre.ac.uk In partnership with: Yale Center for British Art 1080 Chapel Street New Haven, Connecticut https://britishart.yale.edu ISSN: 2058-5462 DOI: 10.17658/issn.2058-5462 URL: https://www.britishartstudies.ac.uk Editorial team: https://www.britishartstudies.ac.uk/about/editorial-team Advisory board: https://www.britishartstudies.ac.uk/about/advisory-board Produced in the United Kingdom. A joint publication by Contents Curating the Cosmopolis, Iwona Blazwick and Rattanamol Singh Johal Curating the Cosmopolis Iwona Blazwick and Rattanamol Singh Johal Abstract Century City: Art and Culture in the Modern Metropolis was the first temporary exhibition mounted at Tate Modern from February to April 2001. -

National Portrait Gallery Account 2002-2003

MUSEUMS AND GALLERIES ACT 1992 Account, of the National Portrait Gallery prepared pursuant to Act 1992, c.44, para 9(7) for the year ended 31 March 2003, together with the Report of the Comptroller and Auditor General thereon. (In continuation of House of Commons Paper No. 1138 of 2001-2002.) Presented pursuant to Museums and Galleries Act 1992, c. 44, para. 9(8). National Portrait Gallery Account 2002-2003 ORDERED BY THE HOUSE OF COMMONS TO BE PRINTED 16 JULY 2003 LONDON: The Stationery Office 30 October 2003 HC 1019 £8.50 The National Audit Office scrutinises public spending on behalf of Parliament. The Comptroller and Auditor General, Sir John Bourn, is an Officer of the House of Commons. He is the head of the National Audit Office, which employs some 800 staff. He, and the National Audit Office, are totally independent of Government. He certifies the accounts of all Government departments and a wide range of other public sector bodies; and he has statutory authority to report to Parliament on the economy, efficiency and effectiveness with which departments and other bodies have used their resources. Our work saves the taxpayer millions of pounds every year. At least £8 for every £1 spent running the Office. This account can be found on the National Audit Office web site at www.nao.gov.uk National Portrait Gallery Account 2002-2003 Contents Page Foreword and Annual Report 2 Annex to the Foreword 12 Statement of Trustees’ and Directors’ responsibilities 13 Statement on Internal Control 14 The Certificate and Report of the Comptroller and Auditor General 15 Summary Income and Expenditure Account 17 Statement of Financial Activities 18 Balance Sheet 20 Cash Flow Statement 21 Notes to the Accounts 22 1 National Portrait Gallery Account 2002-2003 Foreword and Annual Report Status The Museums and Galleries Act 1992 established the corporate status of the Board of Trustees of the National Portrait Gallery. -

State 17QUN Layout 1

FREE 17 | HOT&COOL ART SETTING THE PACE ROBERT FRASER BRIAN CLARKE 2014 BRIAN CLARKE ADVENTURES IN ART DAFYDD JONES KLAUS STAUDT LIGHT AND TRANSCENDENCE ams Trust Albert Ad © , Acrylic on canvas, 127 x 114cm , Acrylic on canvas, The Captive image: Klaus Staudt (b. 1932 Otterndorf am Main, Germany) 1/723 SG 86, Diagonal, 1992, Acrylic, wood and plexiglas, 76.5 x 76.5 x 7.5 cm, 30 1/8 x 30 1/8 x 3 inches ALBERT ADAMS (1930 – 2006) PAINTINGS AND ETCHINGS THE MAYOR GALLERY %46-0ď 21 CORK STREET, FIRST FLOOR, LONDON W1S 3LZ 30 May – 10 July 2015 UNIVERSITY GALLERY Northumbria University Sandyford Road Newcastle upon Tyne NE1 8ST TEL: +44 (0) 20 7734 3558 FAX: +44 (0) 20 7494 1377 T: 0191 227 4424 E: [email protected] www.universitygallery.co.uk [email protected] www.mayorgallery.com 29 MAY 2015 CHARLIE SMITH london Anti-Social Realism Curated by Juan Bolivar & John Stark 3 April – 9 May 2015 Dominic Shepherd 15 May – 20 June 2015 Emma Bennett 26 June – 25 July 2015 336 Old Street, London EC1V 9DR, United Kingdom +44 (0)20 7739 4055 | [email protected] www.charliesmithlondon.com | @CHARLIESMITHldn Wednesday–Saturday 11am–6pm or by appointment Emma Bennett, ‘Tender Visiting’, 2014 Oil on canvas 50x40cm Visiting’, Emma Bennett, ‘Tender DIARY NOTES COVER IMAGE DAFYDD JONES Brian Clarke, 2015 Photographed at Pace Gallery Burlington Gardens London FOOLS RUSH IN Brian Clarke added curating to his many talents when he agreed The FRANCIS BACON MB Art Foundation, established by Majid Boustany and based in to produce a tribute to his former agent, gallerist and friend, Robert Fraser. -

Establishing Tate Modern: Vision and Patronage

Establishing Tate Modern: Vision and Patronage The London School of Economics and Political Science Establishing Tate Modern: Vision and Patronage Caroline Donnellan A thesis submitted to the Department of Sociology at the London School of Economics for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, London, July 2013 1 Establishing Tate Modern: Vision and Patronage Declaration I certify that the thesis I have presented for examination for the Ph.D. degree of the London School of Economics and Political Science is solely my own work, other than where I have clearly indicated that it is the work of others, in which case the extent of any work carried out jointly by me and any other person is clearly identified in it. The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. Quotation from it is permitted, provided that full acknowledgement is made. This thesis may not be reproduced without the prior written consent of the author. I warrant that this authorisation does not, to the best of my belief, infringe the rights of any third party. 2 Establishing Tate Modern: Vision and Patronage Abstract Tate Modern has attracted significant academic interest aimed at analysing its cultural and urban regeneration impact. Yet there exists no research which provides an in-depth and contextual framework examining how Tate Modern was established, nor is there a study which assesses critically the development of Tate’s collection of international modern and contemporary art. Why is this important? It is relevant because a historic conflict of interests developed within the Tate’s founding organisation which was reluctant to host it. -

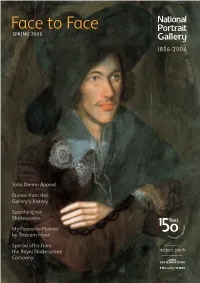

Face to Face SPRING 2006

Face to Face SPRING 2006 John Donne Appeal Stories from the Gallery’s history Searching for Shakespeare My Favourite Portrait by Tristram Hunt Special offer from the Royal Shakespeare Company From the Director ‘Often I have found a Portrait superior in real instruction to half-a-dozen written “Biographies”… or rather I have found that the Portrait was a small lighted candle by which Biographies could for the first t ime be read.’ RIGHT FROMLEFT Marjorie ‘Mo’ Mowlam by John Keane, 2001 Dame (Jean) Iris Murdoch by Tom Phillips, 1984–86 Sir Tim Berners-Lee by Adam Broomberg and Oliver Chanarin, 2005 These portraits can be seen in Icons and Idols: Commissioning Contemporary Portraits from 2 March 2006 in the Porter Gallery So wrote Thomas Carlyle in 1854 in the years leading up to the founding of the National Exhibition supported by the Patrons of the National Portrail Gallery Portrait Gallery in 1856. Carlyle, with Lord Stanhope and Lord Macaulay, was one of the founding fathers of the Gallery, and his mix of admiration for the subject and interest in the character portrayed remains a strong thread through our work to this day. Much else has changed over the years since the first director, Sir George Scharf, took up his Very sadly John Hayes, Director of the National Portrait Gallery role, and as well as celebrating his achievements in a special display, we have created a from 1974 to 1994, died on timeline which outlines all the key events throughout the Gallery’s history. Our first Christmas Day aged seventy-six. -

Stephen Willats

STEPHEN WILLATS Born 1943 in London Lives and works in London SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2019 Stephen Willats: Languages of Dissent, Migros, Zurich 2018 Stephen Willats: CONTROL, Tate Liverpool, UK Stephen Willats: ENDLESS, Galerie Thomas Schulte, Berlin, Germany 2017 HUMAN RIGHT, Middlesbrough Institute of Modern Art, Middlesbrough, UK 2016 Stephen Willats: Conversations With Buildings, Galerie Reinhard Hauff, Stuttgart THISWAY, Index, Stockholm Stephen Willats, Villa Merkel, Esslingen Stephen Willats, Galerie Balice Hertling, Paris 2015 Publishing Interventions–Stephen Willats–Selected Publications 1965 – 2015, Tenderpixel, London Stephen Willats, Step Change, Lumen Travo, Amsterdam, Netherlands Stephen Willats: Man from the 21st Century, Museo Tamayo Arte Contemporáneo, Mexico City, Mexico 2014 Strange Attractor Series No 28, Corner Space, Galerie Thomas Schulte, Berlin Stephen Willats: Berlin Local, MD72, Berlin, Germany Stephen Willats: How Tomorrow Looks From Here, DAAD Galerie, Berlin, Germany Stephen Willats: Attracting the Attractor, Anne Mosseri-Marlio Galerie, Basel, Switzerland Concrete Block: Drawings & Works on Paper, 1978 - 2005, MOT International, Brussels, Belgium Concerning Our Present Way of Living, Whitechapel Gallery, London, England Representing the Possible, Victoria Miro, London, England Control: Work 1962-69, Raven Row, London, England 2013 Living for Tomorrow, Galerie Balice Hertling, Paris (2013 – 2014) World Without Objects, Annie Gentils Gallery, Antwerp, Belgium World of Objects, Galerie Reinhard Hauff, Stuttgart, Germany -

An Investigation of the Architectural, Urban, and Exhibit Designs of the Tate Museums

An Investigation of the Architectural, Urban, and Exhibit Designs of the Tate Museums by Deirdre L. C. Hennebury A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Architecture) in the University of Michigan 2014 Doctoral Committee: Professor Robert L. Fishman, Co-chair Associate Professor Claire A. Zimmerman, Co-chair Associate Professor Scott D. Campbell Professor Raymond A. Silverman The chief function of the city is to convert power into form, energy into culture, dead matter into the living symbols of art, biological reproduction into social creativity. Lewis Mumford, The City in History (1961) For Eric ii Acknowledgements It is a pleasure to be able to thank those who have helped me to write and research this dissertation over many years. Thank you first to my dedicated co-chairs, Robert Fishman and Claire Zimmerman, and committee members, Scott Campbell and Ray Silverman, who despite my meanderings, stayed the course and provided timely and insightful commentary to buoy me along. Thank you also to David Scobey who many years ago first suggested I investigate the University of Michigan’s Museum Studies program; a program that has offered countless benefits to this project and my intellectual development. As the grateful recipient of a Museum Studies Fellowship for Doctoral Research in Museums, I was able to do the travel and research required to complete this work. In Ray Silverman and Brad Taylor, I found examples of generous and talented scholars who are also very fine people. Thank you. I am endlessly grateful to the University of Michigan’s Rackham Graduate School and Doctoral Program in Architecture for the fellowships and grant opportunities I have received throughout my years in Ann Arbor. -

National Portrait Gallery Annual Report and Accounts 2015-16

National Portrait Gallery Annual Report and Accounts 2015-16 Presented to Parliament pursuant to Section 9(8) of the Museums and Galleries Act 1992 Ordered by the House of Commons to be printed 19 July 2016 HC 453 © National Portrait Gallery copyright 2016 The text of this document (this excludes, where present, the Royal Arms and all departmental or agency logos) may be reproduced free of charge in any format or medium provided that it is reproduced accurately and not in a misleading context. The material must be acknowledged as National Portrait Gallery copyright and the document title specified. Where third party material has been identified, permission from the respective copyright holder must be sought. Any enquiries related to this publication should be sent to us at [email protected]. You can download this publication from our website at www.npg.org.uk. This publication is available at https://www.gov.uk/government/publications. Print ISBN 9781474128698 Web ISBN 9781474128704 ID 15021605 07/16 Printed on paper containing 75% recycled fibre content minimum Printed in the UK by the Williams Lea Group on behalf of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office Page Trustees’ and Accounting Officer’s Annual Report 2 Remuneration Report 24 Statement of Trustees’ and Director’s Responsibilities 34 Governance Statement 35 The Certificate and Report of the Comptroller and Auditor General 44 Consolidated Statement of Financial Activities 46 Gallery Statement of Financial Activities 47 Consolidated Balance Sheet 48 Gallery Balance Sheet 49 Consolidated Cash Flow Statement 50 Notes to the Accounts 51 1 TRUSTEES’ AND ACCOUNTING OFFICER’S ANNUAL REPORT INTRODUCTION The Trustees of the National Portrait Gallery have pleasure in submitting their Annual Report and Accounts for the year ended 31st March 2016. -

National Portrait Gallery Annual Report and Accounts 2015-16

National Portrait Gallery Annual Report and Accounts 2015-16 Presented to Parliament pursuant to Section 9(8) of the Museums and Galleries Act 1992 Ordered by the House of Commons to be printed 19 July 2016 HC 453 56073 HC 453 Cover / sig1 / plateA National Portrait Gallery Annual Report and Accounts 2015-16 Presented to Parliament pursuant to Section 9(8) of the Museums and Galleries Act 1992 Ordered by the House of Commons to be printed 19 July 2016 HC 453 © National Portrait Gallery copyright 2016 The text of this document (this excludes, where present, the Royal Arms and all departmental or agency logos) may be reproduced free of charge in any format or medium provided that it is reproduced accurately and not in a misleading context. The material must be acknowledged as National Portrait Gallery copyright and the document title specified. Where third party material has been identified, permission from the respective copyright holder must be sought. Any enquiries related to this publication should be sent to us at [email protected]. You can download this publication from our website at www.npg.org.uk. This publication is available at https://www.gov.uk/government/publications. Print ISBN 9781474128698 Web ISBN 9781474128704 ID 15021605 07/16 Printed on paper containing 75% recycled fibre content minimum Printed in the UK by the Williams Lea Group on behalf of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office Page Trustees’ and Accounting Officer’s Annual Report 2 Remuneration Report 24 Statement of Trustees’ and Director’s Responsibilities 34 Governance Statement 35 The Certificate and Report of the Comptroller and Auditor General 44 Consolidated Statement of Financial Activities 46 Gallery Statement of Financial Activities 47 Consolidated Balance Sheet 48 Gallery Balance Sheet 49 Consolidated Cash Flow Statement 50 Notes to the Accounts 51 1 TRUSTEES’ AND ACCOUNTING OFFICER’S ANNUAL REPORT INTRODUCTION The Trustees of the National Portrait Gallery have pleasure in submitting their Annual Report and Accounts for the year ended 31st March 2016. -

National Portrait Gallery Annual Report and Accounts 2008-2009 HC

MUSEUMS AND GALLERIES ACT 1992 Presented to Parliament pursuant to Museums and Galleries Act 1992, section 9(8) National Portrait Gallery Annual Report and Accounts 2008-2009 ORDERED BY THE HOUSE OF COMMONS TO BE PRINTED 16 JULY 2009 LONDON: The Stationery Office 16 July 2009 HC 770 £10.50 MUSEUMS AND GALLERIES ACT 1992 Presented to Parliament pursuant to Museums and Galleries Act 1992, section 9(8) National Portrait Gallery Annual Report and Accounts 2008-2009 ORDERED BY THE HOUSE OF COMMONS TO BE PRINTED 16 JULY 2009 LONDON: The Stationery Office 16 July 2009 HC 770 £10.50 © Crown Copyright 2009 The text in this document (excluding the Royal Arms and other departmental or agency logos) may be reproduced free of charge in any format or medium providing it is reproduced accurately and not used in a misleading context. The material must be acknowledged as Crown copyright and the title of the document specified. Where we have identified any third party copyright material you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. For any other use of this material please write to Office of Public Sector Information, Information Policy Team, Kew, Richmond, Surrey TW9 4DU or e-mail: licensing@opsi. gov.uk ISBN: 978 0 10 296034 1 The National Audit Office scrutinises public spending on behalf of Parliament. The Comptroller and Auditor General Amyas C E Morse, is an Officer of the House of Commons. He is the head of the National Audit Office, which employs some 800 staff. He, and the National Audit Office, are totally independent of Government. -

Historic Wales and United Kingdom Sites for BYU Wales Study Abroad

Historic Wales and United Kingdom Sites for BYU Wales Study Abroad Volume 2 H–R Compiled by Ronald Schoedel Contents Articles Hadrian's Wall 1 Hampton Court Palace 10 Harlech Castle 20 Hay-on-Wye 27 Hill fort 31 Isca Augusta 39 Kenilworth Castle 43 Kidwelly Castle 61 King Doniert's Stone 62 King's College Chapel, Cambridge 63 Lacock 66 Lacock Abbey 68 Lanhydrock 71 Lanyon Quoit 74 Llandaff Cathedral 75 Malvern Hills 80 Margam Stones Museum 98 Monmouth 110 Monmouth Castle 126 Museum of London 130 Mên-an-Tol 135 National Assembly for Wales 137 National Eisteddfod of Wales 146 National Gallery 151 National Museum Cardiff 168 National Museum of Scotland 171 National Portrait Gallery, London 176 National Railway Museum 181 National Roman Legion Museum 194 National Slate Museum 195 Newcastle Castle, Bridgend 196 North Hill, Malvern 197 Offa's Dyke 199 Ogmore Castle 203 Old Beaupre Castle 205 Old Sarum 207 Oxford University Museum of Natural History 211 Oxfordshire 217 Palace of Whitehall 224 Pierhead Building 228 Plas Mawr 231 Preston England Temple 232 Raglan Castle 235 Roman Baths (Bath) 247 Roman Baths Museum 253 Royal Monmouthshire Royal Engineers 254 Royal Shakespeare Company 256 References Article Sources and Contributors 264 Image Sources, Licenses and Contributors 268 Article Licenses License 278 Hadrian's Wall 1 Hadrian's Wall Hadrian's Wall (Latin: Vallum Aelium, "Aelian Wall" – the Latin name is inferred from text on the Staffordshire Moorlands Patera) was a defensive fortification in Roman Britain. Begun in 122 AD, during the rule of emperor Hadrian, it was the first of two fortifications built across Great Britain, the second being the Antonine Wall, lesser known of the two because its physical remains are less evident today.