Wang 1 Hannah Wang 8 April 2019 Kids in the Basement: Space And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

João Pedro Brito Cício De Carvalho

Universidade do Minho Escola de Economia e Gestão João Pedro Brito Cício de Carvalho eams Business Models in Professional Electronic ts T Sports Teams Business Models in Professional Electronic Spor tins Coelho abio José Mar F 5 1 UMinho|20 April, 2015 Universidade do Minho Escola de Economia e Gestão João Pedro Brito Cício de Carvalho Business Models in Professional Electronic Sports Teams Dissertation in Marketing and Strategy Supervisor: Professor Doutor Vasco Eiriz April, 2015 DECLARATION Name: João Pedro Brito Cício de Carvalho Electronic mail: [email protected] Identity Card Number: 13011205 Dissertation Title: Business Models in Professional Electronic Sports Teams Supervisor: Professor Doutor Vasco Eiriz Year of completion: 2015 Title of Master Degree: Marketing and Strategy IT IS AUTHORIZED THE FULL REPRODUCTION OF THIS THESIS/WORK FOR RESEARCH PURPOSES ONLY BY WRITTEN DECLARATION OF THE INTERESTED, WHO COMMITS TO SUCH; University of Minho, ___/___/______ Signature: ________________________________________________ Thank You Notes First of all, I’d like to thank my family and my friends for their support through this endeavor. Secondly, a big thank you to my co-workers and collaborators at Inygon and all its partners, for giving in the extra help while I was busy doing this research. Thirdly, my deepest appreciation towards my interviewees, who were extremely kind, helpful and patient. Fourthly, a special thank you to the people at Red Bull and Zowie Gear, who opened up their networking for my research. And finally, my complete gratitude to my research supervisor, Professor Dr. Vasco Eiriz, for his guidance, patience and faith in this research, all the way from the theme proposed to all difficulties encountered and surpassed. -

“PRESENCE” of JAPAN in KOREA's POPULAR MUSIC CULTURE by Eun-Young Ju

TRANSNATIONAL CULTURAL TRAFFIC IN NORTHEAST ASIA: THE “PRESENCE” OF JAPAN IN KOREA’S POPULAR MUSIC CULTURE by Eun-Young Jung M.A. in Ethnomusicology, Arizona State University, 2001 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2007 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by Eun-Young Jung It was defended on April 30, 2007 and approved by Richard Smethurst, Professor, Department of History Mathew Rosenblum, Professor, Department of Music Andrew Weintraub, Associate Professor, Department of Music Dissertation Advisor: Bell Yung, Professor, Department of Music ii Copyright © by Eun-Young Jung 2007 iii TRANSNATIONAL CULTURAL TRAFFIC IN NORTHEAST ASIA: THE “PRESENCE” OF JAPAN IN KOREA’S POPULAR MUSIC CULTURE Eun-Young Jung, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2007 Korea’s nationalistic antagonism towards Japan and “things Japanese” has mostly been a response to the colonial annexation by Japan (1910-1945). Despite their close economic relationship since 1965, their conflicting historic and political relationships and deep-seated prejudice against each other have continued. The Korean government’s official ban on the direct import of Japanese cultural products existed until 1997, but various kinds of Japanese cultural products, including popular music, found their way into Korea through various legal and illegal routes and influenced contemporary Korean popular culture. Since 1998, under Korea’s Open- Door Policy, legally available Japanese popular cultural products became widely consumed, especially among young Koreans fascinated by Japan’s quintessentially postmodern popular culture, despite lingering resentments towards Japan. -

Download and Upload Speeds for Any Individual Device That Is Connected to the Network

UC Irvine UC Irvine Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Acceleration and Information: Managing South Korean Online Gaming Culture Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/2204k0wv Author Rea, Stephen Campbell Publication Date 2015 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, IRVINE Acceleration and Information: Managing South Korean Online Gaming Culture DISSERTATION submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in Anthropology by Stephen C. Rea Dissertation Committee: Associate Professor Keith M. Murphy, Chair Professor Tom Boellstorff Professor Bill Maurer 2015 © 2015 Stephen C. Rea TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS iii CURRICULUM VITAE v ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION vi CHAPTER 1: Playing at the Speed of Life: Korean Online Gaming Culture and the 1 Aesthetic Representations of an Advanced Information Society CHAPTER 2: “Slow to Industrialize, but Let’s Lead in Informatization”: The Korea 31 Information Infrastructure, the IMF, and Online Games CHAPTER 3: Situating Korean Online Gaming Culture Offline 71 CHAPTER 4: Managing the Gap: The Temporal, Spatial, and Social Entailments of 112 Playing Online Games CHAPTER 5: Crafting Stars: e-Sports and the Professionalization of Korean Online 144 Gaming Culture CHAPTER 6: “From Heroes to Monsters”: “Addiction” and Managing Online Gaming 184 Culture CONCLUSION 235 BIBLIOGRAPHY 242 ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This dissertation would not have been -

Esports Yearbook 2017/18

Julia Hiltscher and Tobias M. Scholz eSports Yearbook 2017/18 ESPORTS YEARBOOK Editors: Julia Hiltscher and Tobias M. Scholz Layout: Tobias M. Scholz Cover Photo: Adela Sznajder, ESL Copyright © 2019 by the Authors of the Articles or Pictures. ISBN: to be announced Production and Publishing House: Books on Demand GmbH, Norderstedt. Printed in Germany 2019 www.esportsyearbook.com eSports Yearbook 2017/18 Editors: Julia Hiltscher and Tobias M. Scholz Contributors: Sean Carton, Ruth S. Contreras-Espinosa, Pedro Álvaro Pereira Correia, Joseph Franco, Bruno Duarte Abreu Freitas, Simon Gries, Simone Ho, Matthew Jungsuk Howard, Joost Koot, Samuel Korpimies, Rick M. Menasce, Jana Möglich, René Treur, Geert Verhoeff Content The Road Ahead: 7 Understanding eSports for Planning the Future By Julia Hiltscher and Tobias M. Scholz eSports and the Olympic Movement: 9 A Short Analysis of the IOC Esports Forum By Simon Gries eSports Governance and Its Failures 20 By Joost Koot In Hushed Voices: Censorship and Corporate Power 28 in Professional League of Legends 2010-2017 By Matthew Jungsuk Howard eSports is a Sport, but One-Sided Training 44 Overshadows its Benefits for Body, Mind and Society By Julia Hiltscher The Benefits and Risks of Sponsoring eSports: 49 A Brief Literature Review By Bruno Duarte Abreu Freitas, Ruth S. Contreras-Espinosa and Pedro Álvaro Pereira Correia - 5 - Sponsorships in eSports 58 By Samuel Korpimies Nationalism in a Virtual World: 74 A League of Legends Case Study By Simone Ho Professionalization of eSports Broadcasts 97 The Mediatization of DreamHack Counter-Strike Tournaments By Geert Verhoeff From Zero to Hero, René Treurs eSports Journey. -

Historiography of Korean Esports: Perspectives on Spectatorship

International Journal of Communication 14(2020), 3727–3745 1932–8036/20200005 Historiography of Korean Esports: Perspectives on Spectatorship DAL YONG JIN Simon Fraser University, Canada As a historiography of esports in Korea, this article documents the very early esports era, which played a major role in developing Korea’s esports scene, between the late 1990s and the early 2000s. By using spectatorship as a theoretical framework, it articulates the historical backgrounds for the emergence of esports in tandem with Korea’s unique sociocultural milieu, including the formation of mass spectatorship. In so doing, it attempts to identify the major players and events that contributed to the formation of esports culture. It periodizes the early Korean esports scene into three major periods—namely, the introduction of PC communications like Hitel until 1998, the introduction of StarCraft and PC bang, and the emergence of esports broadcasting and the institutionalization of spectatorship in the Korean context until 2002. Keywords: esports, historiography, spectatorship, youth culture, digital games In the late 2010s, millions of global youth participated in esports as gamers and viewers every day. With the rapid growth of various game platforms, in particular, online and mobile, people around the world enjoy these new cultural activities. From elementary school students to college students, to people in their early careers, global youth are deeply involved in esports, referring to an electronic sport and the leagues in which players compete through networked games and related activities, including the broadcasting of game leagues (Jin, 2010; T. L. Taylor, 2015). As esports attract crowds of millions more through online video streaming services like Twitch, the activity’s popularity as one of the most enjoyable sports and business products continues to soar. -

The Effect of School Closure On

Public Gaming: eSport and Event Marketing in the Experience Economy by Michael Borowy B.A., University of British Columbia, 2008 Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in the School of Communication Faculty of Communication, Art, and Technology Michael Borowy 2012 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY Summer 2012 All rights reserved. However, in accordance with the Copyright Act of Canada, this work may be reproduced, without authorization, under the conditions for “Fair Dealing.” Therefore, limited reproduction of this work for the purposes of private study, research, criticism, review and news reporting is likely to be in accordance with the law, particularly if cited appropriately. Approval Name: Michael Borowy Degree: Master of Arts (Communication) Title of Thesis: Public Gaming: eSport and Event Marketing in the Experience Economy Examining Committee: Chair: David Murphy, Senior Lecturer Dr. Stephen Kline Senior Supervisor Professor Dr. Dal Yong Jin Supervisor Associate Professor Dr. Richard Smith Internal Examiner Professor Date Defended/Approved: July 06, 2012 ii Partial Copyright Licence iii STATEMENT OF ETHICS APPROVAL The author, whose name appears on the title page of this work, has obtained, for the research described in this work, either: (a) Human research ethics approval from the Simon Fraser University Office of Research Ethics, or (b) Advance approval of the animal care protocol from the University Animal Care Committee of Simon Fraser University; or has conducted the research (c) as a co-investigator, collaborator or research assistant in a research project approved in advance, or (d) as a member of a course approved in advance for minimal risk human research, by the Office of Research Ethics. -

Esports Yearbook 2015/16 Esports Yearbook Editors: Julia Hiltscher and Tobias M

Julia Hiltscher and Tobias M. Scholz eSports Yearbook 2015/16 ESPORTS YEARBOOK Editors: Julia Hiltscher and Tobias M. Scholz Layout: Tobias M. Scholz Cover: Photo: P.Strack, ESL Copyright © 2017 by eSports Yearbook and the Authors of the Articles or Pictures. ISBN: to be announced Production and Publishing House: Books on Demand GmbH, Norderstedt. Printed in Germany 2017 www.esportsyearbook.com eSports Yearbook 2015/16 Editors: Julia Hiltscher and Tobias M. Scholz Contributors: Viktor Barie, Ho Kai Sze Brenda, Isaque Renovato de Araujo, Fernando Por- fírio Soares de Oliveira, Rolf Drenthe, Filbert Goetomo, Christian Esteban Martín Luján, Marc-Andre Messier, Patrick Strack Content Preface 7 by Julia Hiltscher and Tobias M. Scholz Spectating the Rift: A Study into eSports Spectatorship 9 by Ho Kai Sze Brenda Informal Roles within eSport Teams: A Content Analysis of the Game 36 Counter-Strike: Global Offensive by Rolf Drenthe A Turning Point for FPS Games 49 by Marc-André Messier “Reverse-Gamification” Analysis of the Crowding-Out Effects 52 in eSports by Viktor Barie ONLINPCS: From Olympics to Eletrônics 71 by Isaque Renovato de Araujo, Fernando Porfírio Soares de Oliveira eSports in Korea: A Study on League of Legends Team Performances 79 on the Share Price of Owning Corporations by Filbert Goetomo Ergonomics and Videogames: Habits, Diseases and Health 95 Perception of Gamers by Christian Esteban Martín Luján - 6 - Preface By Julia Hiltscher and Tobias M. Scholz You seem to hear it every year: eSports is growing and can be described as a global phenome- non. We are yet once more stunned by events such as Amazon’s purchase of Twitch for nearly 1 billion dollars. -

Ing-Yeo Subjectivity and Youth Culture In

Being Surplus in the Age of New Media: Ing-yeo Subjectivity and Youth Culture in South Korea A Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at George Mason University by Sangmin Kim Master of Arts Seoul National University, 2002 Bachelor of Science Korea Advanced Institute of Science and Technology, 1993 Director: Hugh Gusterson Affiliate Faculty, Cultural Studies, George Mason University Professor, Anthropology and International Affairs, George Washington University Fall Semester 2015 George Mason University Fairfax, VA This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License ii DEDICATION This dissertation is dedicated to my parents, Boosoo Kim and Chaerip Song, and my parents-in-law, Chungsik Yu and Myungja Woo. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I am honored to have worked with my dissertation committee. I would first like to express my sincere gratitude to my academic advisor and dissertation chair, Hugh Gusterson. His thorough scholarship and social engagement as a social scientist serve as a model for my academic life. I would like to thank Alison Landsberg and Tim Gibson for their generous and encouraging feedback as well as inspiring teaching in visual culture and media studies. In addition, I would like to thank Roger Lancaster, Denise Albanese, and Paul Smith for introducing me to the fascinating field of cultural studies. I am indebted to my many colleagues in the cultural studies program. I am especially grateful to my mentor Vicki Watts, who supported and encouraged me to overcome hardships during my early years. Rob Gehl, Jarrod Waetjen, Nayantara Sheoran, Fan Yang, Jessi Lang, Randa Kayyali, Cecilia Uy-Tioco, David Arditi, Dava Simpson, Ozden Ocak, and Adila Laïdi-Hanieh have all been wonderful colleagues. -

Systemic Barriers to Participation in South Korea Florence M

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Loyola eCommons Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons School of Communication: Faculty Publications Faculty Publications and Other Works 2016 A Game Industry Beyond Diversity: Systemic Barriers to Participation in South Korea Florence M. Chee Loyola University Chicago, [email protected] Recommended Citation Chee, Florence M.. A Game Industry Beyond Diversity: Systemic Barriers to Participation in South Korea. Diversifying Barbie and Mortal Kombat: Intersectional Perspectives and Inclusive Designs in Gaming, , : 159-170, 2016. Retrieved from Loyola eCommons, School of Communication: Faculty Publications and Other Works, This Book Chapter is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Publications at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in School of Communication: Faculty Publications and Other Works by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. © ETC Press, 2016 CHAPTER 11. A GAME INDUSTRY BEYOND DIVERSITY Systemic Barriers to Participation for Women in South Korea BY FLORENCE M. CHEE Digital gaming has become a prominent part of mainstream culture. However, as one may observe in the public exhibitions of this form of play, the multitude of reasons for participation in the games industry are especially divided along gender lines. This paper is an analysis of themes emerging from the critical ethnographic examination of South Korea’s1 online game culture that, upon closer and iterative analyses, point to additional socioeconomic complications and systemic barriers to women’s equitable participation in the game development and production. -

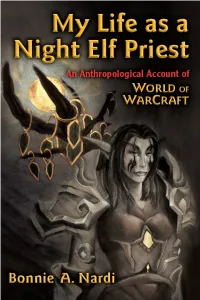

My Life As a Night Elf Priest Technologies of the Imagination New Media in Everyday Life Ellen Seiter and Mimi Ito, Series Editors

My Life as a Night Elf Priest technologies of the imagination new media in everyday life Ellen Seiter and Mimi Ito, Series Editors This book series showcases the best ethnographic research today on engagement with digital and convergent media. Taking up in-depth portraits of different aspects of living and growing up in a media-saturated era, the series takes an innovative approach to the genre of the ethnographic monograph. Through detailed case studies, the books explore practices at the forefront of media change through vivid description analyzed in relation to social, cultural, and historical context. New media practice is embedded in the routines, rituals, and institutions—both public and domes- tic—of everyday life. The books portray both average and exceptional practices but all grounded in a descriptive frame that renders even exotic practices understandable. Rather than taking media content or technology as determining, the books focus on the productive dimensions of everyday media practice, particularly of children and youth. The emphasis is on how specific communities make meanings in their engagement with convergent media in the context of everyday life, focus- ing on how media is a site of agency rather than passivity. This ethnographic approach means that the subject matter is accessible and engaging for a curious layperson, as well as providing rich empirical material for an interdisciplinary scholarly community examining new media. Ellen Seiter is Professor of Critical Studies and Stephen K. Nenno Chair in Television Studies, School of Cinematic Arts, University of Southern California. Her many publications include The Internet Playground: Children’s Access, Entertainment, and Mis-Education; Television and New Media Audiences; and Sold Separately: Children and Parents in Consumer Culture. -

For Peer Review

Games and Culture Roger Caillois and e -Sports: On the Problems of Treating Play as Work Journal:For Games Peer and Culture Review Manuscript ID GAMES-15-0168.R3 Manuscript Type: Caillois Special Issue Reflexivity, Roger Caillois, Margaret Archer, Professional Gaming, Play, Keywords: Work, Match Fixing, e-Sports In Man, Play and Games, Roger Caillois warns against the ‘rationalisation’ of play by working life and argues that the professionalisation of competitive games (agôn) will have a negative impact on people and society. In this article, I elaborate on Caillois’ argument by suggesting that the professional context of electronic sports (e-Sports) rationalises play by Abstract: turning player psychology towards the pursuit of extrinsic rewards. This is evidenced in the instrumental decision-making that accompanies competitive gameplay as well as the ‘survival’ strategies that e-Sports players deploy to endure its precarious working environment(s). In both cases, play is treated as work and has problematic psychological and sociological implications as a result. http://mc.manuscriptcentral.com/sage/games Page 1 of 30 Games and Culture 1 2 3 Roger Caillois and e-Sports: On the Problems of Treating Play as Work 4 5 6 Abstract 7 8 9 In Man, Play and Games , Roger Caillois warns against the ‘rationalisation’ of play by 10 working life and argues that the professionalisation of competitive games (agôn) will 11 have a negative impact on people and society. In this article, I elaborate on Caillois’ 12 argument by suggesting that the professional context of electronic sports (e-Sports) 13 rationalises play by turning player psychology towards the pursuit of extrinsic 14 rewards. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Discourses Of

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Discourses of Connectedness: Globalization, Digital Media, and the Language of Community A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Anthropology by Lisa Ann Newon 2014 © Copyright by Lisa Ann Newon 2014 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Discourses of Connectedness: Globalization, Digital Media, and the Language of Community by Lisa Ann Newon Doctor of Philosophy in Anthropology University of California, Los Angeles, 2014 Professor Marjorie Harness Goodwin, Chair This dissertation provides both ethnographic and linguistic analysis of how translocality and transidiomatic practices intersect the ways in which people organize their social worlds in the digital and information age. I explore how translocality informs how people understand, construct, and experience a voluntary and avocational community and identity in their everyday lives, through the lens of a global, video gaming community, centered around a game called League of Legends. In this dissertation, I focus on understanding how distributed players and developers together co-construct a sense of community, belonging, and connectivity, through both language and interaction online and offline. This analysis first discusses how players and developers co-construct community and identity through language, distinctiveness, and authenticity. The data in this dissertation is used ii to highlight how players and developers use language in their everyday interactions to construct particular group identities, through specific lexical and material styles. I then discuss how a sense of community and belonging are constructed in the social network through moral participation and engagement, both institutionally and endogenously, looking particularly at stance, directives, assessments, and structure-preserving transformations.