RURAL ENCOUNTERS in MEDIEVAL ESPOO the Emergence And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Visitors Guide

ENGLISH VISITORS GUIDE VISIT HELSINKI.FI INCLUDES MAP Welcome to Helsinki! Helsinki is a modern and cosmopolitan city, the most international travel des- tination in Finland and home to around 600,000 residents. Helsinki offers a wide range of experiences throughout the year in the form of over 3000 events, a majestic maritime setting, classic and contemporary Finnish design, a vibrant food culture, fascinating neighbourhoods, legendary architecture, a full palette of museums and culture, great shopping opportunities and a lively nightlife. Helsinki City Tourism Brochure “Helsinki – Visitors Guide 2015” Published and produced by Helsinki Marketing Ltd | Translated into English by Crockford Communications | Design and layout by Helsinki Marketing Ltd | Main text by Helsinki Marketing Ltd | Text for theme spreads and HEL YEAH sections by Heidi Kalmari/Matkailulehti Mondo | Printed in Finland by Forssa Print | Printed on Multiart Silk 130g and Novapress Silk 60g | Photos by Jussi Hellsten ”HELSINKI365.COM”, Visit Finland Material Bank | ISBN 978-952-272-756-5 (print), 978-952-272-757-2 (web) This brochure includes commercial advertising. The infor- mation within this brochure was updated in autumn 2014. The publisher is not responsible for possible changes or for the accuracy of contact information, opening times, prices or other related information mentioned in this brochure. CONTENTS Sights & tours 4 Design & architecture 24 Maritime attractions 30 Culture 40 Events 46 Helsinki for kids 52 Food culture & nightlife 60 Shopping 70 Wellness & exercise 76 Outside Helsinki 83 Useful information 89 Public transport 94 Map 96 SEE NEW WALKING ROUTES ON MAP 96-97 FOLLow US! TWITTER - TWITTER.COM/VISITHELSINKI 3 HELSINKI MOMENTS The steps leading up to Helsinki Cathedral are one of the best places to get a sense of this city’s unique atmosphere. -

Espoon Ja Kauniaisten Lippukunnat Esite

Partio on maailman paras harrastus artio on maailman paras harras- tus. Se on vastavoima “Miks mun Ppitäis?” ja “Ei kuulu mulle!” -asen- teille. Partio on seikkailuja ja elämyksiä, jotka kasvattavat luottamusta omiin ky- kyihin. Se opettaa arjen taitoja, ryhmässä toimimista ja toimeen tarttumista. Asiat opitaan yhdessä tekemällä. Partiossa jokainen kuuluu ryhmään ja kasvaa kantamaan oman vastuunsa. Partio on kaikille, joita kiinnostaa monipuolinen ja luonnonläheinen toiminta yhdessä toisten kanssa. Kuva: Anna Enbuske @Partiokuuluukaikille #partioscout #päpa www.pääkaupunkiseudunpartiolaiset.fi Espoon ja Kauniaisten lippukuntien yhteystiedot Kauniainen ORAVANMARJAT RY oravanmarjat.fi Kuva: Mikko Jalo Suur-Kauklahti TOIMEN POJAT RY Espoonkartano, Kauklahti, Kurttila, toimenpojat.fi Vanttila Pohjois-Espoo KAUKA-KUUTIT RY kauku.wordpress.com Bodom, Kalajärvi, Kunnarla, Lahnus, Lakisto, Luukki, Niipperi, Röylä, Velskola NIIPPERIN NUOLIHAUKAT RY Suur-Leppävaara niinu.com Karakallio, Kilo, Laaksolahti, Leppävaara, Lintuvaara, Lippajärvi, Sepänkylä, - POHJOIS ESPOON KALAHAUKAT RY Viherlaakso kalahaukat.fi KARA-KARHUT RY Suur-Espoonlahti karka.partio.net Kaitaa, Kivenlahti, Latokaski, Laurinlahti, KILON KIPINÄT RY Nöykkiö, Saunalahti, Soukka, Suvisaaristo kilonkipinat.fi HAUKKAVUOREN HALTIAT RY haukkavuorenhaltiat.net LEPPÄVAARAN KORVENKÄVIJÄT RY leppavaarankorvenkavijat.fi KARHUNVARTIJAT RY karhunvartijat.net PITKÄJÄRVEN VAELTAJAT RY pitkajarvenvaeltajat.fi KASKENPOLTTAJAT RY kaskenpolttajat.net SUSIVUOREN VAELTAJAT RY KIVENLAHDEN PIILEVÄT RY -

Alueet Ja Aukeamisajat Ympäristökunnat

10 / 2019 Aluenro Aluenimi Ennakko auki Inva/5-8H Paarit Ensisij. haku Taksiasema Espoo min min min 211 Otaniemi 15 25 35 212 Otaniemi metro 213 Tapiola 15 25 35 214 Tapiontori 215 Westend 15 25 35 216 Westend bussias. 217 Keilaniemi 15 25 35 218 Keilaniementie 221 Haukilahti 15 25 35 222 Haukil.ostari 223 Olarinluoma 15 25 35 224 Olarinluoma 225 Mankkaa 15 25 35 226 Mankkaan Ostari 227 Tapiola Pohjoinen 15 25 35 228 Pohjantori 229 Niittykumpu 15 25 35 230 Niittykumpu as. 231 Matinkylä 15 25 35 232 Matink. Anjankuja 235 Olari 15 25 35 236 Olari, Kuunkehrä 237 Suomenoja 15 25 35 238 Suomenoja 241 Soukka 15 25 35 242 Soukan ostari 243 Espoonlahti 20 30 40 244 Ulappatori 245 Kivenlahti 20 30 40 246 Merivirta 247 Latokaski 20 30 40 248 Latokaski, Kaskenp. 251 Perkkaa 15 25 35 252 Leppävaara Sello 253 Leppävaara 15 25 35 254 Läkkitori 257 Laajalahti 15 25 35 258 Laajalahti, Kirvuntie 261 Kilo 20 30 40 262 Kilo, Kutojantie 263 Kauniainen 20 30 40 264 Kauniainen juna-as. 265 Laaksolahti 20 30 40 266 Lähderanta 267 Karakallio 15 25 35 268 Karaportti 271 Tuomarila 20 30 40 alue 273 Kirstinharju 20 30 40 274 Espoontori 275 Espoon keskus 20 30 40 276 Espoon juna-as. 277 Kauklahti 20 30 40 278 Kauklahti juna-as. 281 Bemböle 20 30 40 282 Jorvin sairaala 283 Järvenperä 20 30 40 284 Auroranportti 285 Nupuri 20 30 40 alue Sivu 1 / 7 10 / 2019 Aluenro Aluenimi Ennakko auki Inva/5-8H Paarit Ensisij. -

Linjaluettelo Linjeförteckning

Linjaluettelo Linjeförteckning Palvelulinjat / Servicelinjer Tapiolan palvelulinjat / Hagalunds servicelinjer info P10 Oravannahkatori - Tapiola Gråskinnstorget - Hagalund P11 Haukilahti - Tapiola Gäddvik - Hagalund P12 Pohjois-Tapiola - Tapiola Norra Hagalund - Hagalund P13 Tapiola - Hopealehto - Itäranta - Tapiola Hagalund - Silverlunden - Österstranden - Hagalund P14 Niittymaa - Tapiola Ängsmalmen - Hagalund Suur-Leppävaaran palvelulinjat / Alberga servicelinjer P20 Leppävaara - Lintulaakso Alberga - Fågeldalen P21 Leppävaara - Karakallio - Rastaspuisto Alberga - Karabacka - Trastparken Espoonlahden palvelulinjat / Esbovikens servicelinjer P40 Kivenlahti - Soukka - Iivisniemi Stensvik - Sökö - Ivisnäs P41 Kivenlahden palvelulinja Stensvik servicelinje P50 Kauniaisten palvelulinja / Grankulla servicelinje Espoon keskuksen kutsulinja / Esbo centrums flexlinje P80 Espoon keskus / Ymmersta / Kuurinniitty / Nupuri / Mikkelä / Kauklahti Esbo centrum / Ymmersta / Kurängen / Nupurböle / Mickels / Köklax Espoon ja Kauniaisten suunnan bussilinjat Esbo och Grankulla busslinjer 2 Otaniemi - Tapiola - Soukka Otnäs - Hagalund - Sökö 3 Leppävaara - Nihtisilta - Soukka - Kivenlahti Alberga - Knektbro - Sökö - Stensvik 4 Otaniemi - Tapiola - Kivenlahti Otnäs - Hagalund - Stensvik 5 Leppävaara - Nihtisilta - Suurpelto - Olari - Matinkylä Alberga - Knektbro - Storåkern - Olars - Mattby 10 Otaniemi - Pohjois-Tapiola - Tapiola - Westend - Haukilahti - Matinkylä - Puolarmetsä Otnäs - Norra Hagalund - Hagalund - Westend - Gäddvik - Mattby - Bolarskog 11 Tapiola -

Espoon Niittyjen Ja Avointen Alueiden Toimenpideohjelma 2021-2031

Espoon niittyjen ja avointen alueiden toimenpideohjelma 2021–2031 Julkaisija: Kaupunkitekniikan keskus, Viherkunnossapito, luonnonhoito. 2021 Valokuvat: ProAgria Etelä-Suomi, Auli Hirvonen; Ramboll Finland Oy Tuulikki Peltomäki ja Mervi Kokkila Kannen kuva: Etuniemi, Ruostenopsasiipi / ProAgria Etelä-Suomi, Auli Hirvonen Taitto: Ramboll Finland Oy / Aija Nuoramo 2 ESPOON NIITTYJEN JA AVOINTEN ALUEIDEN TOIMENPIDEOHJELMA 2021–2031 Sisältö Espoon niittyjen ja avointen alueiden toimenpideohjelman käsitteitä: . 4 Tiivistelmä . 6 Johdanto . 7 Työn tavoitteet ja sisältö ................................................7 Toimenpideohjelman liittyminen muihin ohjelmiin...........................8 Työskentelymenetelmät.................................................8 OSA I . 10 1 Tarkastelualueen nykytilan analyysi . 11 1.1 Maisema- ja kulttuuriympä ris tö arvot ................................11 1.1.1 Espoon maanviljelyn historiaa ..................................13 1.2 Luontoarvot ...................................................13 1.3 Virkistysarvot ..................................................16 1.4 Siniverkosto ja olosuhteet.........................................16 1.5 Analyysin yhteenveto ............................................21 2 Niittyverkostosuunnitelma . .22 2.1 Niittyverkostosuunnitelma .......................................22 3 Avoimien viheralueiden kunnossapito . .28 3.1 Kunnossapidon nykytila .........................................28 3.2 Haastatteluiden yhteenveto – näkemyksiä kentältä .....................30 3.3 -

Helsinki Visitors Guide.Pdf

English visitors guide Photo: Rami Hanafi Photo: Welcome to Helsinki! Helsinki City Tourism Brochure “Helsinki – Visitors Guide 2014” Published and produced by Helsinki Travel Marketing Ltd | Translated into English by Crockford Communications | Design and layout by Helsin- ki Travel Marketing Ltd | Main text by Helsinki Travel Marketing Ltd | Text for theme spreads and local specialties: Heidi Kalmari/Matkailulehti Mondo | Printed in Finland by Forssa Print | Printed on Multiart Silk 130g and Novapress Silk 60g | Photos from Helsinki City Image Bank, Helsinki Tourism Material Bank, Visit Finland Material Bank and advertisers | ISBN 978-952-272-566-0 (print), 978-952-272-567-7 (web) This brochure includes commercial advertising. The information within this brochure was updated in autumn 2013. The publisher is not responsible for possible changes or for the accuracy of contact information, opening times, prices or other related information mentioned in this brochure. 2 Helsinki is a modern and cosmopolitan city, the most international travel destination CONTENTS in Finland and home to around 600,000 residents. Helsinki offers a wide range of Attractions & tours 4 experiences throughout the year in the form Design & architecture 25 of over 3000 events, a majestic maritime setting, classic and contemporary Finnish Maritime attractions 31 design, a vibrant food culture, fascinating neighbourhoods, legendary architecture, a Culture 38 full palette of museums and culture, great shopping opportunities and a lively nightlife. Events 46 Follow us! Facebook - Visithelsinki Helsinki for kids 53 Blog - blog.visithelsinki.fi Twitter - twitter.com/HelsinkiTourism Food culture & nightlife 59 www.visithelsinki.fi Shopping 71 Wellness & exercise 76 Outside Helsinki 83 Useful information 89 Public transport 94 Map 95 How to use the Quick Response Code The Quick Response (QR) Code is a two-dimensional barcode that can be decoded and read using a smartphone with a QR Code Reader application. -

Espoon Ja Kauniaisten Bussilinjat 15.8.2016 Alkaen Linjat, Joiden Numero Tai Reitti Muuttuu, on Merkitty Listaan Sinisellä Värillä

Espoon ja Kauniaisten bussilinjat 15.8.2016 alkaen Linjat, joiden numero tai reitti muuttuu, on merkitty listaan sinisellä värillä. Linjojen kirjainversiot ja reitit pysyvät samoina kuin nykyään, ellei erikseen mainita. Vanha Uusi numero Reitti Huom. numero 3 3 Leppävaara–Nihtisilta–Soukka–Kivenlahti 5 5 Leppävaara–Nihtisilta–Suurpelto–Matinkylä 10 10 Otaniemi–Pohjois-Tapiola–Haukilahti–Matinkylä– Puolarmetsä 11 11 Tapiola–Matinkylä–Friisilänaukio 12 12 Tapiola–Soukka 14 14 Tapiola–Kivenlahti 15 15 Otaniemi–Tapiola–Kauniainen–Jupperi 16 16 Matinkylä–Olari–Henttaa 18 18 Tapiola–Kauniainen–Espoon keskus–Mikkelä– Kauklahti 19 19 Tapiola–Espoon keskus–Tuomarilan asema 20 219 Leppävaara–Karakallio–Lähderanta–Järvenperä 21 236 Leppävaara–Viherlaakso–Kalajärvi–Lahnus 22 202 Leppävaara–Helmipöllönmäki 23 203 Uusmäki–Painiitty–Leppävaara–Säteri– Vitikka/Laajalahti 24 214 Leppävaara–Rastaala–Veini–Jupperi 25 215 Leppävaara–Laaksolahti–Lähderanta/Högnäs 26 226 Leppävaara–Karakallio–Viherlaaksonranta–Jorvi 27 227 Leppävaara–Karakallio–Lippajärvi–Espoon keskus 28 238 Leppävaara–Nupuri– Siikajärvi/Siikaniemi/Siikaranta 29 239 Leppävaara–Viherlaakso–Punametsä–Kalajärvi 31 31 Friisilänaukio–Matinkylä–Espoon keskus–Jorvi 38 38 Elielinaukio–Pitäjänmäki–Uusmäki 42 42 Soukka–Kivenlahti–Espoon keskus–Jorvi 46 46 Hyljelahti–Espoon keskus 51 - Linja lakkautetaan. Ks. linja 224. 65 65 Espoonlahti–Kauklahti 70 348 Rinnekoti–Röylä–Kalajärvi 71 349 Lepsämänjoki–Kalajärvi–Lahnus–Röylä 81 241 Espoon keskus–Mikkelänkallio–Gumböle–Hirvisuo 82 582 Espoon keskus–Juvanmalmi–Kalajärvi/Lahnus -

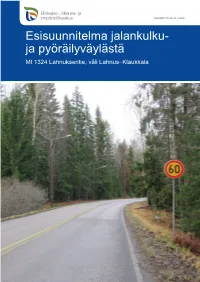

Esisuunnitelma Jalankulku

RAPORTTEJA 23 I 2019 Esisuunnitelma jalankulku- ja pyöräilyväylästä Mt 1324 Lahnuksentie, väli Lahnus–Klaukkala Esisuunnitelma jalankulku- ja pyöräily- väylästä Mt 1324 Lahnuksentie, väli Lahnus - Klaukkala RAPORTTEJA 23 | 2019 Esisuunnitelma jalankulku- ja pyöräilyväylästä Lahnuksentie Mt 1324, väli Lahnus – Klaukkala Uudenmaan elinkeino-, liikenne- ja ympäristökeskus Kansikuva: Kati Palo-Junttila ISBN 978-952-314-785-0 (PDF) ISSN 2242-2854 (verkkojulkaisu) URN:ISBN:978-952-314-785-0 www.doria.fi/ely-keskus Sisältö 1. Esipuhe .................................................................................................................................................... 2 2. Lähtökohdat ja tavoitteet ......................................................................................................................... 3 2.1. Lähtökohdat .................................................................................................................................. 3 2.2. Tavoitteet ....................................................................................................................................... 3 3. Nykytilan kuvaus ...................................................................................................................................... 4 3.1. Tiestö ja liikenne ........................................................................................................................... 4 3.1.1. Jalankulku- ja pyöräily ......................................................................................................... -

Bayesian Hierarchical Models for Housing Prices in the Helsinki-Espoo-Vantaa Region

Bayesian hierarchical models for housing prices in the Helsinki-Espoo-Vantaa region Ville M¨akinen March 29, 2020 HELSINGIN YLIOPISTO — HELSINGFORS UNIVERSITET — UNIVERSITY OF HELSINKI Tiedekunta/Osasto — Fakultet/Sektion — Faculty Laitos — Institution — Department Matemaattis-luonnontieteellinen Matematiikan ja tilastotieteen laitos Tekijä — Författare — Author Ville Mäkinen Työn nimi — Arbetets titel — Title Bayesian hierarchical models for housing prices in the Helsinki-Espoo-Vantaa region Oppiaine — Läroämne — Subject Matematiikka Työn laji — Arbetets art — Level Aika — Datum — Month and year Sivumäärä — Sidoantal — Number of pages Pro gradu -tutkielma Maaliskuu 2020 87 s. Tiivistelmä — Referat — Abstract Tässä tutkielmassa esitellään bayesläisten hierarkisten mallien käyttöä asuntojen hintojen mallinta- miseen. Tutkielmassa käytetään aineistoa, jossa kuvataan tapahtuneita asuntokauppoja Helsingistä, Espoosta ja Vantaalta. Tutkielmassa estimoidaan yhteensä viisi robustia regressiomallia. Malleissa käytetään Studentin t- jakaumaa likelihood-jakaumana, sillä aineistotarkastelut antavat viitteitä tietojen kirjausvirheistä. Neljässä mallissa on hierarkinen rakenne, joka perustuu myytyjen asuntojen kaupunginosiin. Mal- leista tuotetaan myös yhdistelmämalli käyttäen n.k. model stacking-menetelmää. Mallien toimivuutta tarkastellaan posterior-jakaumasta johdettavien ennustejakaumien perusteella: Ennustejakaumista poimitaan otos, jonka perusteella muodostetaan jakaumat valituille tunnuslu- vuille. Tunnuslukujen jakaumia verrataan oikeasta aineistosta -

Long-Term Changes in Groundwater Chemistry in Four Coastal Water Supply Plants in Southern Finland

BOREAL ENVIRONMENT RESEARCH 4: 175–186 ISSN 1239-6095 Helsinki 18 June 1999 © 1999 Long-term changes in groundwater chemistry in four coastal water supply plants in southern Finland Enn Karro Department of Geology, University of Helsinki, P.O. Box 11, FIN-00014 University of Helsinki, Finland & Institute of Geology, University of Tartu, Vanemuise 46, 51014 Tartu, Estonia Karro, E. 1999. Long-term changes in groundwater chemistry in four coastal water supply plants in southern Finland. Boreal Env. Res. 4: 175–186. ISSN 1239-6095 Monitoring of four glacial outwash aquifers that have been utilised during the last 30 years for municipal water supply of Espoo community, southern Finland, reveals changes in chemical composition of groundwater. A 1.5 to 2.0-fold increase in electrical con- ductivity and in concentrations of main cations and anions in abstracted groundwater reflect primarily the geological impact of Litorina deposits. Relict seawater trapped in deeper parts of aquifers and leaching of fossil salts from postglacial clay and silt depos- its have a marked effect on the chemistry of groundwater. Introduction burden and bedrock along coastal regions of Fin- land (Hyyppä 1984, Lahermo and Lampén 1987, During late phases of deglaciation the Baltic ba- Lahermo 1991, Mitrega and Lahermo 1991, Kork- sin was occupied by a larger water body than the ka-Niemi 1994). This phenomenon has been at- present sea. Owing to eustatic changes in sea level tributed primarily to relict salts left deep in glacio- and the concomitant isostatic uplift of the central marine deposits and within fractures and fissures part of the Baltic Shield, the basin gradually di- of bedrock during the Litorina stage (about 7 500– minished in size until it reached its present areal 5 000 years ago). -

European Stress Tests for Nuclear Power Plants National Report

European Stress Tests for Nuclear Power Plants National Report FINLAND 3/0600/2011 December 30, 2011 Tomi Routamo (ed.) © Radiation and Nuclear Safety Authority 2011 Radiation and Nuclear Safety Authority Report i (xvii) 3/0600/2011 Nuclear Reactor Regulation December 30, 2011 Public CONTENTS Abbreviations ................................................................................................................................................................ x Authors ......................................................................................................................................................................... xii Executive summary ................................................................................................................................................. xiii A. Background information on National Report .......................................................................................... 1 A.1 General view on NPPs and nuclear power regulation in Finland ........................................................... 1 A.2 Earthquakes – seismicity in Finland and Finnish requirements ............................................................. 3 A.3 Flooding – Finnish requirements ......................................................................................................................... 7 A.4 Extreme weather conditions – Finnish requirements .............................................................................. 10 A.5 Electrical power supply – Finnish requirements -

Nuuksion Kansallispuiston Hoito- Ja Käyttösuunnitelma

Nuuksion kansallispuiston hoito- ja käyttösuunnitelma Metsähallituksen luonnonsuojelujulkaisuja. Sarja C 19 Nuuksion kansallispuiston hoito- ja käyttösuunnitelma Översättning: Cajsa Rudbacka-Lax Kansikuva: Harmaapäätikka (Picus canus). Kuva Antti Below © Metsähallitus 2006 ISSN 1796-2943 ISBN 952-446-537-X (nidottu) ISBN 952-446-538-8 (pdf) 150 kpl Kopijyvä Oy, Jyväskylä 2006 KUVAILULEHTI JULKAISIJA Metsähallitus JULKAISUAIKA 2006 TOIMEKSIANTAJA Metsähallitus HYVÄKSYMISPÄIVÄMÄÄRÄ 5.9.2006 LUOTTAMUKSELLISUUS Julkinen DIAARINUMERO 1057/623/2003 SUOJELUALUETYYPPI/ kansallispuisto, Natura 2000, lehtojensuojeluohjelma, rantojensuojeluohjelma, vanhojen metsien SUOJELUOHJELMA suojeluohjelma ALUEEN NIMI Nuuksion kansallispuisto NATURA 2000- ALUEEN Nuuksion Natura-alue (FI0100040) NIMI JA KOODI ALUEYKSIKKÖ Etelä-Suomen luontopalvelut TEKIJÄ(T ) Metsähallitus JULKAISUN NIMI Nuuksion kansallispuiston hoito- ja käyttösuunnitelma TIIVISTELMÄ Tämä hoito- ja käyttösuunnitelma koskee Vihdin, Espoon ja Kirkkonummen kunnissa sijaitsevaa Nuuksion kansallispuistoa, joka perustettiin vuonna 1994 annetulla lailla (118/1994) valtion omis- tamille alueille, tuolloin laajuudeltaan 1620 hehtaaria. Laissa asetettiin tavoitteeksi kansallispuiston huomattava laajentaminen. Maanhankinta on kohdistunut lähinnä Natura-alueelle ostoin ja maan- vaihdoin niin, että 1.1.2002 kansallispuiston pinta-ala oli 3681 hehtaaria, josta vettä 67 ha. Tämä suunnitelma on samalla luontodirektiivin (92/43/ETY) 6 artiklan 1 kohdan edellyttämä Nuuksion Natura 2000 -alueen käyttösuunnitelma