Gypsy and Traveller Accommodation Assessment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Wander Around Walton and Small Moor

A Listed as Waltone in the Doomsday book, this area was an estate of Glastonbury Abbey since at least the 8th century. Walton is situated on a woody hill, also known as a wold, which is where the name Walton may have derived from; it is also suggested that it could Avalon Marshes Heritage Walks: mean settlement of the Welsh. During 1753 the main road through Walton (now the A39) became a turnpike road; the route is part of the Wells Trust, with the road being known as A wander around Walton the ‘Western Road’ south west of the City of Wells and the ‘Bristol Road’ to the north. The Church of the Holy Trinity in Walton was built in 1866 by John Norton; the first church recorded was Norman, built around 1150. and Small Moor B Whitley wood gave its name to the Whitley Hundred (a county administrative division) which was probably formed in the latter part of the 12th century; it still contains the ruins of the Hundred house which was a meeting place for the Hundred court. C Small Moor was added to the parish of Walton during inclosure; prehistoric flints and fragments of medieval pottery have been found there. D On 22nd April 1707 Henry Fielding was born at Sharpham Park, a novelist and playwright well known for the novel ‘The history of Tom Jones, a foundling’. Fielding was also London’s Chief Magistrate for a time and with the help of his half-brother John, formed the Bow Street Runners. E Abbot’s Sharpham was built by the Abbott Richard Beere of Glastonbury Abbey; it was here the last Abbott of Glastonbury, Richard Whiting, was arrested before his execution on Glastonbury Tor. -

Gosh Locations

GOSH LOCATIONS - APRIL POSTAL COUNCIL ALTERNATIVE SECTOR NAME MONTH (DATES) SECTOR BA1 1 AVON - Bath and North East Somerset Council St James's Parade, Bath 01.04.19-28.04.19 BA1 2 AVON - Bath and North East Somerset Council Royal Crescent, Bath 01.04.19-28.04.19 BA1 3 AVON - Bath and North East Somerset Council Bath (Incl Lower Weston) 01.04.19-28.04.19 BA1 4 AVON - Bath and North East Somerset Council Bath (Incl Weston) 01.04.19-28.04.19 BA1 5 AVON - Bath and North East Somerset Council Bath (Incl Lansdown) 01.04.19-28.04.19 BA1 6 AVON - Bath and North East Somerset Council Bath (Incl Larkhall, Walcot) 01.04.19-28.04.19 BA1 7 AVON - Bath and North East Somerset Council Batheaston, Bathford 01.04.19-28.04.19 BA1 8 AVON - Bath and North East Somerset Council Upper Swainswick, Batheaston 01.04.19-28.04.19 BA1 9 AVON - Bath and North East Somerset Council Kelston, Lansdown, North Stoke 01.04.19-28.04.19 BA2 0 AVON - Bath and North East Somerset Council Timsbury, Farmborough 01.04.19-28.04.19 BA2 1 AVON - Bath and North East Somerset Council Bath (Incl Twerton, Southdown, Whiteway) 01.04.19-28.04.19 BA2 2 AVON - Bath and North East Somerset Council Odd Down, Bloomfield, Bath 01.04.19-28.04.19 BA2 3 AVON - Bath and North East Somerset Council Bath (Incl Twerton) 01.04.19-28.04.19 BA2 4 AVON - Bath and North East Somerset Council Bath (Incl Bathwick) 01.04.19-28.04.19 BA2 5 AVON - Bath and North East Somerset Council Bath (Incl Combe Down) 01.04.19-28.04.19 BA2 6 AVON - Bath and North East Somerset Council Bath (Incl Bathampton, Bathwick, Widcombe) 01.04.19-28.04.19 BA2 7 AVON - Bath and North East Somerset Council Limpley Stoke, Norton St. -

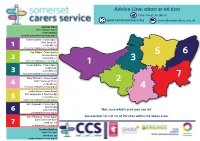

A3 Map and Contacts

Amanda Stone Carers Support Agent 07494 883 654 [email protected] Elaine Gardner - Carers Agent West Somerset 07494 883 134 C D 1 [email protected] Kay Wilton - Carers Agent A Taunton Deane ? 07494 883 541 2 [email protected] Lauren Giddins - Carers Agent Sedgemoor E 07494 883 579 3 [email protected] @ Mary Withams - Carers Agent B South Somerset (West) 4 07494 883 531 [email protected] Jackie Hayes - Carers Agent East Sedgemoor & West Mendip 07494 883 570 5 [email protected] John Lapwood - Carers Agent East Mendip 07852 961 839 Not sure which area you are in? 6 [email protected] Cath Holloway - Carers Agent See overleaf for full list of Parishes within the above areas South Somerset (East) 07968 521 746 7 [email protected] Caroline Harding Agent Manager 07908 160 733 [email protected] 1 2 • Ash Priors • Corfe • Norton Fitzwarren • Thornfalcon • Bicknoller • Exton • Oare • Washford • Ashbrittle • Cotford St Luke • Nynehead • Tolland • Brompton Ralph • Exford • Old Cleeve • Watchet • Bathealton • Cothelstone • Oake • Trull • Brompton Regis • Exmoor • Porlock • West Quantoxhead • Bishops Hull • Creech St Michael • Orchard Portman • West Bagborough • Brushford • Holford • Sampford Brett • Wheddon • Bishops Lydeard • Curland • Otterford • West Buckland • Carhampton • • Selworthy • Winsford • Bickenhall • Durston • Pitminster • West Hatch • Clatworthy • Kilve • Skilgate • Williton • Bradford-on-Tone • Fitzhead • Ruishton • Wellington -

Somerset Mineral Plan - Mailing List

Somerset Mineral Plan - Mailing list JOB TITLE/INDIVIDUAL COMPANY ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT COMPTON PAUNCEFOOT & BLACKFORD PARISH INDIVIDUAL INDIVIDUAL INDIVIDUAL INDIVIDUAL INDIVIDUAL BICKNOLLER PROJECT INDIVIDUAL INDIVIDUAL Planning Policy & Research North Somerset Council Bickenhall House INDIVIDUAL RSPB (SW) Wells Cathedral Stonemasons Ltd INDIVIDUAL ASSET MANAGER NEW EARTH SOLUTIONS INDIVIDUAL INDIVIDUAL Dorset County Council INDIVIDUAL INDIVIDUAL INDIVIDUAL Blackdown Hills Business Association INDIVIDUAL INDIVIDUAL INDIVIDUAL John Wainwright And Co Ltd Chard Chamber Of Commerce Geologist Crewkerne Chamber Of Commerce INDIVIDUAL INDIVIDUAL INDIVIDUAL MENDIP POWER GROUP Institute Of Historic Building Conservation INDIVIDUAL SUSTAINABLE SHAPWICK FAITHNET SOUTH WEST INDIVIDUAL INDIVIDUAL INDIVIDUAL INDIVIDUAL HALLAM LAND MANAGEMENT Mendip SOUTH PETHERTON Wellington Chamber Of Commerce INDIVIDUAL CANFORD RENEWABLE ENERGY INDIVIDUAL INDIVIDUAL INDIVIDUAL INDIVIDUAL Eclipse Property Investments Ltd MAY GURNEY CHEDDAR PARISH COUNCIL SOMERSET WILDLIFE TRUST Mendip PILTON PARISH COUNCIL Hanson Aggregates INDIVIDUAL DIRECTOR GENERAL THE CONFEDERATION OF UK COAL PRODUCERS DIRECTOR GENERAL CONFEDERATION OF UK COAL PRODUCERS (COALPRO) Ecologist Somerset Drainage Boards Consortium SOMERSET DRAINAGE BOARD INDIVIDUAL AXBRIDGE TOWN COUNCIL WELLS ENVIRONMENT PROTECTION GROUP INDIVIDUAL INDIVIDUAL Senior Planning Officer - Minerals And Waste Policy Gloucestershire County Council Minerals Review Group INDIVIDUAL Shepton Mallet Town Council INDIVIDUAL MEARE -

10212 the London Gazette, 20Th September 1968

10212 THE LONDON GAZETTE, 20TH SEPTEMBER 1968 *Land to north of Manor Farm, Chew Stoke. fLand comprising Holes 'Square Corner and road The Pound, Poor Hill, Farmborough. to Croydon House, Timberscombe. *Shortwood Common, Hinton Blewett. Part of West Quantoxhead Common, West Land at Wollard's Hill, Publow. Quantoxhead. Old Down, Pensford, Stanton Drew. *Dunkery Hill, Wootton Courtenay. •Wick Green, Button Wick, Stowey Sutton. *Burledge Common in parishes of Stowey Sutton Wincanton R.D. and West Harptree. Chargrove Hill, South Brewham, Brewham. Widcombe Common, Bushy Common, Little The Common and Shave Lane, South Brewham, Common and Stitching and Lower Common and Brewham. Withy Lane, West Harptree. Part of Street Lane, South Brewham, Brewham. The Old Horse Pond, Penselwood. Dulverton R.D. *Leigh Common, Stoke Trister. *Bye Common, Winsford. "tTemple Lane, Templecombe. "fWithypool Hil, Withypool Common, Hawkridge Common and Bradymoor, Withypool. Yeovil R.D. *Worth Hill, Withypool. Land at Fairhouse Road, Barwick. *Land to south of New Bridge, Withypool. Land adjoining Lufton Churchyard, Brympton. Chiselborough Common, Chiselborough. Frame R.D. Fairplace, Chiselborough. *Mells Green, Mells. Part of River Parrett, Martock. Egypt, Mells. The Borough, Montacute. The Paddock, Lower Vobster, Mells. Pikes Moor, South Petherton. Lyde Green, Norton St. Philip. Land at the Coronation Tree, Tintinhull. Langport R.D. The Village Pump, Farm Street, Tintinhull. The Village Pound, Fivehead. Dower House Verge, Tintinhull. Huish Common Moor, Huish Episcopi. The Car Park, St. Margarets Road, Tintinhull. The Pound, Huish Episcopi. The Pound, Church Street, Tintinhull. The Lock-up and Village Green and part of River The Court Verges, St. Margarets Road, Tintinhull. Parrett, Kingsbury Episcopi. -

1 31St July 2020 Dear Chris Harris, in June, Mendip's Cabinet Approved a Project That Aspires to Reduce the Volume of Commuter

31st July 2020 Dear Chris Harris, In June, Mendip’s Cabinet approved a project that aspires to reduce the volume of commuter related vehicles in the District, through the creation of an integrated network of multi-user paths that facilitate walking and cycling to work. The paper can be found here (agenda item 6 https://www.mendip.gov.uk/article/8723/Cabinet- Monday-1-June-2020 We will initially focus on the connections that see the highest volumes of commuters and would therefore have the highest impact in reducing the number of vehicles on our roads through active travel infrastructure. We are initially considering 14 routes across the District: Route 1. Shepton – Emborough Route 8. Frome – Wanstrow Route 2. Shepton – Wanstrow Route 9. Shepton – Evercreech Route 3. Wells – Westbury-sub- Route 10. Wells – Glastonbury Mendip Route 4. Glastonbury – Street Route 11. Glastonbury – Shepton Route 5. Street – Sharpham Route 12. Shepton – Wells Route 13. Street – Walton – (would need Route 6. Sharpham – Glastonbury to connect to a route in Sedgemoor) Route 14. Frome – Bath (would need to Route 7. Connecting Frome connect to a route in BANES) The first step is to work together to gain a clear understanding of the existing infrastructure, related projects both planned and in progress, active volunteer groups, potential and current resources and overall appetite for project delivery in your parish. Some of this work will require audits of the current paths and routes to identify the missing links. After the information has been collated, we will then need to find an ideal proposed route, before creating a delivery strategy – this will also require the physical collection of data. -

Dog Walking on the Nature Reserves Are a Haven for a Broad Array of Relating to Dog Walking

WELCOME WILDLIFE PROTECTION Welcome to the How you can help us protect the wildlife on the Avalon Marshes’ nature reserves. Avalon Marshes’ Nature Reserves: Covering around 1,500 hectares (3,700 acres), the Please look out for and follow signs Dog Walking on the nature reserves are a haven for a broad array of relating to dog walking. wildlife and offer the chance to see some unusual Please keep your dog on a short lead at all Nature Reserves species, rarely seen elsewhere. times (but let go if chased by livestock). This leaflet has been designed to help you and Please keep to the path and don’t allow your dog explore and protect this wonderful your dog in the undergrowth or water as landscape and its wildlife, by providing this disturbs the wildlife. information on where you can walk your dog. No commercial dog walking. Please take your dog waste home with you Throughout the year birds and other species are (don’t ‘stick and flick’ it). using the area to feed and breed, and can easily be disturbed by the approach of people and dogs. In Thank you. addition there may be livestock present. We hope you and your dog have a great visit. We ask you to put wildlife first on the nature reserves by keeping your dog on a lead at all times (but let go of lead if chased by livestock), and not let them enter the water, reedbeds and undergrowth. Registered assistance dogs are welcome on all trails and in hides. Please note there are no dog, or litter, bins on site, due to the high cost of their upkeep, so we ask people to take their dog waste away with them. -

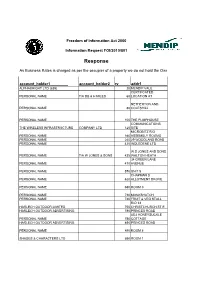

801 Response

Freedom of Information Act 2000 Information Request FOI/2010/801 Response As Business Rates is charged as per the occupier of a property we do not hold the Own account_holder1 account_holder2 rv addr1 ALPHABRIGHT LTD (839) 20 MENDIP VALE CERTIFCATED PERSONAL NAME T/A DB & H MILES 60 LOCATION AT NETHERTON AND PERSONAL NAME 80 COLESHILL PERSONAL NAME 100 THE PUMPHOUSE COMMUNICATIONS THE WIRELESS INFRASTRUCTURE COMPANY LTD 120 SITE MICROBITZ R/O PERSONAL NAME 160 ASSEMBLY ROOMS PERSONAL NAME 240 29 WOODLAND ROAD PERSONAL NAME 420 INDLEDENE LTD W.S JONES AND SONS PERSONAL NAME T/A W JONES & SONS 435 WALTON HEATH 34 GREEN LANE PERSONAL NAME 470 AVENUE PERSONAL NAME 570 UNIT 5 CHAPMAN D PERSONAL NAME 620 ALLOTMENT DROVE PERSONAL NAME 680 ROOM 3 PERSONAL NAME 730 MONKSHATCH PERSONAL NAME 740 FRUIT & VEG STALL R/O 33 HARLECH OUTDOOR LIMITED 750 CHRISTCHURCH ST E HARLECH OUTDOOR ADVERTISING 780 PRINCES ROAD ADJ HONEYSUCKLE PERSONAL NAME 780 COTTAGE HARLECH OUTDOOR ADVERTISING 890 PRINCES ROAD PERSONAL NAME 890 ROOM 8 SHADES & CHARACTERS LTD 890 ROOM 1 HASTOE HOUSING ASSOCIATION LTD 900 COLES GARDEN PERSONAL NAME 900 UNIT 2 4 HAYBRIDGE PERSONAL NAME 900 HOLIDAY COTTAGES T/A HAYBRIDGE 3 HAYBRIDGE PERSONAL NAME HOLIDAY COTTAGES 925 HOLIDAY COTTAGES PERSONAL NAME 930 UNIT 6 C/O THE OLD HARRIET WARBURTON VICARAGE 950 THE COACH HOUSE PERSONAL NAME 980 OLD POOL HEALTH ACADEMICS LTD 1000 1 SEEKINGS WATERFALL PERSONAL NAME 1000 WHITEHOLE FARM PERSONAL NAME T/A G A S 1000 ROOM 8 PERSONAL NAME 1000 ROOM 6 PERSONAL NAME FLAT ABOVE 1000 10 CATHERINE HILL CHARLTON -

Final Recommendations on the Future Electoral Arrangements for Mendip in Somerset

Final recommendations on the future electoral arrangements for Mendip in Somerset Further electoral review August 2006 1 Translations and other formats For information on obtaining this publication in another language or in a large-print or Braille version please contact the Boundary Committee for England: Tel: 020 7271 0500 Email: [email protected] The mapping in this report is reproduced from OS mapping by the Electoral Commission with the permission of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, © Crown Copyright. Unauthorised reproduction infringes Crown Copyright and may lead to prosecution or civil proceedings. Licence Number: GD 03114G 2 Contents What is the Boundary Committee for England? 5 Executive summary 7 1 Introduction 19 2 Current electoral arrangements 23 3 Draft recommendations 27 4 Responses to consultation 29 5 Analysis and final recommendations 31 Electorate figures 31 Council size 32 Electoral equality 33 General analysis 33 Warding arrangements 34 Frome Berkley Down, Frome Fromefield, Frome Keyford, Frome Park and Frome Welshmill wards 35 Beacon, Beckington & Rode, Coleford, Creech, Mells, Nordinton, Postlebury and Stratton wards 36 Shepton East and Shepton West wards 40 Ashwick & Ston Easton, Avalon, Chilcompton, Knowle, Moor, Nedge, Pylcombe, Rodney & Priddy, St Cuthbert 41 (Out) North & West and Vale wards Wells Central, Wells St Cuthbert’s and Wells St Thomas’ wards 44 Glastonbury St Benedict’s, Glastonbury St Edmund’s, Glastonbury St John’s and Glastonbury St Mary’s wards 45 Street North, Street South and Street West wards 45 Conclusions 47 Parish electoral arrangements 47 6 What happens next? 51 7 Mapping 53 3 Appendices A Glossary & abbreviations 55 B Code of practice on written consultation 59 4 What is the Boundary Committee for England? The Boundary Committee for England is a committee of the Electoral Commission, an independent body set up by Parliament under the Political Parties, Elections and Referendums Act 2000. -

Chris East Sam Jackson Clare Haskins Eve Wynn Sarah

RIGHTS OF WAY WARDEN STRUCTURE CLARE from November 2020 CHRIS EAST HASKINS Shipham CP Brean CP Norton St. Philip CP Lympsham CP Compton Bishop CP Tellisford CP Litton CP Hemington CP Rode CP Priddy CP Ston Easton CP Berrow CP Cheddar CP Chewton Mendip CP East Brent CP Kilmersdon CP Lullington CP Badgworth CP Weare CP Beckington CP Brent Knoll CP Chilcompton CP Buckland Dinham CP Emborough CP ENP Stratton on the Fosse CP SAM Chapel Allerton CP Rodney Stoke CP Coleford CP Binegar CP Berkley CP Great Elm CP Westbury CP Mells CP Burnham Without CP Frome CP Mark CP Ashwick CP Leigh-on-Mendip CP Whatley CP Wedmore CP Selworthy CP JACKSON Nunney CP Minehead CP Otterhampton CP West Huntspill CP St. Cuthbert Out CP Selwood CP ck CP Wookey CP Croscombe CP Downhead CP Stogursey CP East Huntspill CP Luccombe CP Shepton Mallet CP Cranmore CP Dunster CP Stockland Bristol CP Watchet CP Stringston CP Pawlett CP Godney CP Wootton Courtenay CP Burtle CP Doulting CP Wanstrow CP Trudoxhill CP Carhampton CP Kilve CP Puriton CP Woolavington CP Meare CP West Quantoxhead CP North Wootton CP Timberscombe CP Williton CP Fiddington CP Chilton Polden CP Pilton CP Holford CP Nether Stowey CP Edington CP Withycombe CP Sampford Brett CP Chilton Trinity CP Witham Friary CP Cannington CP Bawdrip CP Shapwick CP Cutcombe CP Old Cleeve CP Evercreech CP Batcombe CP Bicknoller CP Sharpham CP Pylle CP Glastonbury CP West Pennard CP Luxborough CP Over Stowey CP Bridgwater Without CP Stawell CP Nettlecombe CP Chedzoy CP Ashcott CP Milton Clevedon CP Stogumber CP Spaxton CP East Pennard CP Treborough CP Crowcombe CP Durleigh CP Moorlinch CP Street CP West Bradley CP Lamyatt CP Brewham CP Winsford CP Ditcheat CP Exton CP Enmore CP Bruton CP Elworthy CP Goathurst CP Westonzoyland CP West Bagborough CP Butleigh CP dge CP West Bradley CP (DET) Middlezoy CP Ansford CP Broomfield CP Barton St. -

Victoria House, Victoria Street, Taunton TA1 3JZ the Community Council for Somerset Is a Company Limited by Guarantee Registered in England and Wales No

STOP PRESS……….EXTENSION OF CLOSING DATE FOR VILLAGE AGENTS APPLICATIONS TO 11 th MAY VILLAGE AGENTS 8 hours per week - salary £12,145 pa pro rata ( plus travel expenses) Approximately £6.65 per hour The Community Council for Somerset is looking to appoint Village Agents to support the first six selected parish ‘clusters’ in Somerset. One Agent to be appointed per cluster Cluster 1: Marston Magna, Corton Denham, Mudford, Queen Camel, Rimpton and West Camel Cluster 2: Creech St Michael, Ruishton, Thornfalcon and West Monkton Cluster 3: Stoke sub Hamdon, Chilthorne Domer, Montacute, Norton sub Hamdon, Odcombe and Tintinhull Cluster 4: Stoke St Gregory, Burrowbridge, Lyng, North Curry and Othery. Cluster 5: Godney, Meare, Sharpham and Wookey. Cluster 6: Chewton Mendip, Binegar, Emborough, Litton, Priddy, Rodney Stoke and Ston Easton Village Agents provide assistance to people living in rural areas, bridging the gap between the local community and the statutory or voluntary organisations and can offer help or support. Candidates will need to be committed to helping vulnerable people, live in or close to the cluster of parishes they serve, be able to communicate effectively, have use of a reliable car and basic IT skills. For further information and an application form, please visit www.somersetrcc.org.uk/latest - news.php or telephone 01823 331222. Closing date for applications is 5.00pm Friday 11th May Interviews will take place week beginning 28th May Victoria House, Victoria Street, Taunton TA1 3JZ The Community Council for Somerset is a Company limited by Guarantee Registered in England and Wales No. 3541219, and is a Registered Charity No. -

Glastonbur Y Street

Westbury-sub-Mendip, G O Cheddar, Wells, D N Wedmore E This cycling map was produced This map is reproduced from Ordnance Survey Y R O A by CycleCity Guides for Somerset material with the permission of Ordnance Survey D County Council. © 2009 on behalf of the Controller of Her Majesty’s 9 3 www.cyclecityguides.co.uk Stationery Office © Crown copyright. Unauthorised A reproduction infringes Crown copyright and may lead Every effort has been made to to prosecution or civil proceedings. ensure the accuracy of these Licence number: 100015871, 2009 maps. Somerset Council and Launcherley, Dinder CycleCity Guides cannot be held responsible for any G VE LASTO DRO NBU errors or omissions. NG RY R LO OAD Y B3 A 151 W E IL T S 0 Kilometres 0.2 0.4 0.6 0.8 1 9 3 A CHASE S 0 Miles 0.2 0.4 0.6 Y'S DR TILE OVE WAY B 31 How long will it take? 51 G O D 3 minutes cycling will take you about this far N E E Y V If you cycle at about 10 miles an hour R HYD O O IT R A W D T 10 minutes walking will take you about this far GR E A If you walk at about 3 miles an hour GL AS TO NB E UR V C Y O RAB T R R RO EE DR A D O D E VE V R 9 O O 3 R O A D M T I N P O K M C A M L A39 O B C B3 151 9 A3 D LS ROA E WEL V D O A R O D M D R R BR E E K INDHAM LAN A Y R 'S IC E B E R N R N R A E OA E E R D C D M G E KR O V G E TE O I V V A R RO RD T D E D N S R B3 R L A E 'S R OCK 1 O O M N K 'S DRO DRO 51 O W Y VE M RR LO C E E A O N R F V R O S V A M I E M D O E C L A L N C D E N 9 A A 3 M O AL L R O O W N E H I RS T ID S E U RD A M D EA A R U O E R R O N S AD LL E D E LAN E LEG