The Path Forward

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MASS CULTURAL COUNCIL Fiscal Year 2018 Grants

MASS CULTURAL COUNCIL Fiscal Year 2018 Grants Grant Recipient FY18 City of Boston City of Boston Artist Fellowship Sidi Mohammed Camara, , 6178523641 $12,000 for artistic professional development. P. Carl, , 612/743-3278 $12,000 for artistic professional development. Eben Haines, , 617/817-1516 $12,000 for artistic professional development. Alexis Ivy, , 617/957-9242 $12,000 for artistic professional development. Josh Jefferson, , 617/390-6700 $12,000 for artistic professional development. Daniel Johnson, , 908/415-1213 $1,000 for artistic professional development. Kieran M. Jordan, , 617/322-9889 $12,000 for artistic professional development. Matthew King, , 617/608-7041 $1,000 for artistic professional development. Jesus Matheus, , 617/244-0696 $12,000 for artistic professional development. Jill McDonough, , 617/921-0973 $1,000 for artistic professional development. Anna V.Q. Ross, , 917/204-2720 $12,000 for artistic professional development. Dariel Suarez, , 857/615-2685 $1,000 for artistic professional development. Michael Zachary, , 617/412-1317 $1,000 for artistic professional development. Big Yellow School Bus Samuel Adams Elementary School, Contact: Joanna Mckeigue-Cruz, 617/635-8383 $200 for an educational field trip. Dante Alighieri School, Contact: Glenda Colon, 617/635-8529 $200 for an educational field trip. MASS CULTURAL COUNCIL Fiscal Year 2018 Grants Grant Recipient FY18 Phineas Bates Elementary School, Contact: Rodolfo Morales, 617/635-8064 $200 for an educational field trip. Berea Seventh-Day Adventist Academy, Contact: Rosalind Aaron, 617/436-8301 $200 for an educational field trip. William Blackstone Elementary School, Contact: Jamel Adkins-Sharif, 617/635-8471 $200 for an educational field trip. Boston Collegiate Charter School, Contact: Sarah Morland, 617/265-1172 $200 for an educational field trip. -

Participating School List 2018-2019

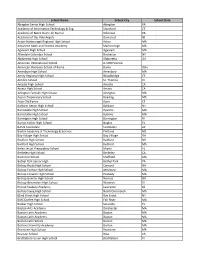

School Name School City School State Abington Senior High School Abington PA Academy of Information Technology & Eng. Stamford CT Academy of Notre Dame de Namur Villanova PA Academy of the Holy Angels Demarest NJ Acton-Boxborough Regional High School Acton MA Advanced Math and Science Academy Marlborough MA Agawam High School Agawam MA Allendale Columbia School Rochester NY Alpharetta High School Alpharetta GA American International School A-1090 Vienna American Overseas School of Rome Rome Italy Amesbury High School Amesbury MA Amity Regional High School Woodbridge CT Antilles School St. Thomas VI Arcadia High School Arcadia CA Arcata High School Arcata CA Arlington Catholic High School Arlington MA Austin Preparatory School Reading MA Avon Old Farms Avon CT Baldwin Senior High School Baldwin NY Barnstable High School Hyannis MA Barnstable High School Hyannis MA Barrington High School Barrington RI Barron Collier High School Naples FL BASIS Scottsdale Scottsdale AZ Baxter Academy of Technology & Science Portland ME Bay Village High School Bay Village OH Bedford High School Bedford NH Bedford High School Bedford MA Belen Jesuit Preparatory School Miami FL Berkeley High School Berkeley CA Berkshire School Sheffield MA Bethel Park Senior High Bethel Park PA Bishop Brady High School Concord NH Bishop Feehan High School Attleboro MA Bishop Fenwick High School Peabody MA Bishop Guertin High School Nashua NH Bishop Hendricken High School Warwick RI Bishop Seabury Academy Lawrence KS Bishop Stang High School North Dartmouth MA Blind Brook High -

Saturday, January 26, 2019

Saturday, January 26, 2019 Saturday, January 26, 2019 Dear students and educators, Greetings and welcome to the 51st annual Berklee High School Jazz Festival. We are so pleased that you are here with us to experience a wonderful day highlighting jazz education and music-making by talented artists. Our participants embody the very best of high school instrumental and vocal jazz in large and small ensemble combinations, as well as solo vocalists in our specialized Jazz Singer Showcase category. We are very proud that our event is the largest of its kind in the United States, featuring thousands of student performers representing public and private high schools from across the country. It also represents hundreds of music educators at the top of their craft who empower and influence students with their teaching every single day. None of the students would be here without their teachers and we honor, appreciate, and acknowledge this fact. One of our goals with the festival is to provide enriching opportunities for young artists to experience jazz from multiple angles (i.e., performing, attending clinics and exhibits, and hearing performances by other musicians). In addition, we recognize the power of bringing music teachers together to showcase the talents and efforts of their students, expand their professional networks, and inspire each other. Accordingly, throughout the day, we have scheduled time for all of these activities, and we encourage you to explore and take advantage of the festival’s many facets. This year, we are pleased to announce that Thomas “TL” Lizotte, band director for Cape Elizabeth High School in Maine, will receive the John LaPorta Jazz Educator of the Year Award. -

2019-2020 Boston Public Schools DIRECTORY

2019-2020 Boston Public Schools DIRECTORY Administrative Departments & Offices Administrative Office Staff School Organization 2019-2020 School Calendar Office Locations Schools Boston School Committee Unions Directory Alternative Programs Boston Public Schools Bruce C. Bolling Municipal Building 2300 Washington St. Roxbury, MA 02119 617-635-9000 www.bostonpublicschools.org OCTOBER 17, 2019 BOSTON SCHOOL DEPARTMENT – CENTRAL OFFICE Bruce C. Bolling Municipal Building 2300 Washington Street (Dudley Square), Roxbury, MA 02119 Bolling Building Directory Floor Ferdinand Washington Waterman Warren Engagement Engagement Roof Deck English Language Partnerships NA Community Rooms Learning 6 WriteBoston Ombudsperson Superintendent Communications Chief of Staff Extended Learning Senior Advisor Opportunities School Superintendent Chief of Engagement NA Team Special Education 5 Operations Safety Services Equity Student Support Opportunity Gaps Human Capital Human Capital Human Capital Human Capital Labor Relations Business Services Recruitment, Cultivation, Office of Secondary Legal Advisor Finance 4 & Diversity (RCD) Schools Planning & Analysis Academics & Professional Learning Data & Accountability ART Student & School Support Informational & Early Childhood School Committee Instructional Technology Excellence for All Informational & 3 Instructional Technology Health & Wellness Turnaround & Library Services Transformation STEM Programming School Committee Newcomers Assessment Meeting Room Innovation Center Transportation Welcome Center -

List of Past Fellows

Massachusetts Education Policy Fellowship Program 2020-2021 Fellows Babatunde Alford, Youth Mentor/Program Associate Summer Search Kristen Almquist-Cevallos, Director of Early College and Career Pathways Boston Plan for Excellence/Dearborn STEM Academy Pola Andrews, Executive Director of Finance & Administration Saugus Public Schools Kelsey Barowich, Campaign Advocacy Specialist American Student Assistance Djamel Bekkai, Coordinator/Program Manager French Heritage Language Program Anna Braet, Engagement Manager Mass Insight Education & Research Kim Connolly, Director, Recruitment, Cultivation & Diversity Programs Boston Public Schools Monica Hall, Administrative Professional Growth Specialist Boston Public Schools Chrissy Howard, Program Manager Reading Success by 4th Grade Esther Jeong, Accountability & Dissemination Specialist Massachusetts Department of Elementary and Secondary Education Kim Merrick, Vice President of Education Wilson Language Training Tiffany Millor, Lead Teacher Codman Academy Charter Public School Sarah Nemetz, BRYT Junior Program Specialist BRYT (Bridge for Resilient Youth in Transition), The Brookline Center for Community Mental Health Deneysha Riley, Executive & Finance Coordinator EdVestors Ralph Saint Louis, High School Science Teacher Lowell High School Sushmita Subedi, Researcher American Institutes for Research (AIR) Patricia Suomala, Director, Career and Technical Education Worcester Technical High School Andrew Volkert, Senior Associate Rennie Center for Education Research & Policy Massachusetts Education -

Program Directory

Chapter 74 Career/Vocational Technical Education Program Directory This book is accurate through November 8, 2017. For current information regarding programs that were added or deleted after November 8, 2017, go to the active Program Directory link at http://profiles.doe.mass.edu/search/search.aspx?leftNavId=11238. MASSACHUSETTS DEPARTMENT OF ELEMENTARY AND SECONDARY EDUCATION Office for Career/Vocational Technical Education 75 Pleasant Street, Malden, MA 02148-4906 Telephone: 781-338-3910 Internet: www.doe.mass.edu/cte/ Email: [email protected] CAREER/VOCATIONAL TECHNICAL EDUCATION CLUSTERS Arts & Communication Agriculture Transportation & Natural Resources Manufacturing, Business & Engineering & Consumer Technology Services Massachusetts Career/Vocational Legal & Technical Education Protective Construction Services Clusters Information Technology Education Services Hospitality & Health Tourism Services 2 | P a g e TABLE OF CONTENTS CAREER/VOCATIONAL TECHNICAL EDUCATION CLUSTERS ...................................................... 2 INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................................................... 4 MASSACHUSETTS MAP OF SCHOOL DISTRICTS WITH CHAPTER 74-APPROVED PROGRAMS .. 5 REGIONAL VOCATIONAL TECHNICAL SCHOOL DISTRICTS ........................................................ 6 LOCAL SCHOOL DISTRICTS ...................................................................................................... 12 ACADEMIC REGIONAL SCHOOL DISTRICTS ............................................................................ -

Program Booklet

AkeelahAkeelah and the BEE October 21 - November 20, 2016 Nov. 17, 18 & 20 2 Wheelock Family Theatre Akeelah and the BEE 3 October/November 2016 Dear Wheelock Family Theatre-goers, As the third show of our 35th season, we’re thrilled to be producing Robert and Willie Reale’s musical A Year with Frog and Toad, based on the beloved books by Arnold Lobel. Written for early readers, Lobel’s stories about friendship have been enjoyed for many generations by people of all generations. A Year with Frog and Toad was originally performed at Children’s Theatre Company and on Broadway by an ensemble of five adult actors. WFT continues to demonstrate its commitment to inclusive professional theatre experiences by casting 21 young thespians to perform alongside seven professional adult actors. WFT also has a strong commitment to accessibility and affordability, and provides tickets and tuition assistance for over 8,000 children, families, and organizations annually with our Theatre for All Fund. At a special benefit performance on April 30, we present the 2016 WHEEL Award – which celebrates individuals who share our commitment to children and families, and belief that the arts transform lives – to Willie Reale. Penning the book and lyrics of A Year with Frog and Toad is but one of Willie Reale’s con- tributions. In 1981, the same year our founders established WFT in Boston, Reale founded the 52nd Street Project to bring children from NYC’s Hell’s Kitchen together with professional theatre artists to create original plays. He was awarded a MacArthur Fellowship in recognition of his ingenuity in creating theatre education programs for young people in 1994. -

In Nature, Rushing River Waters Occasionally Form an Oxbow

In nature, rushing river waters occasionally form an oxbow, carving out a path that exposes new shores and reveals the surrounding environment from perspectives previously unseen. Mission The Oxbow School is an innovative, interdisciplinary semester program for high school students. Our mission is to strengthen students’ abilities in creative and critical inquiry by combining rigorous studio art practice with innovative academics. The Oxbow campus is located on the banks college. At Oxbow, studio art and academic of the Napa River in Northern California. topics are interwoven so that the experience Students enjoy an inspirational natural envi- of research, writing, and making art becomes ronment while still having access to all the an internalized working model for personal amenities of downtown Napa, which is just growth. Socially, the students encounter a short stroll from campus. We are located peers from all over the country and all walks forty-five minutes from San Francisco, one of life; most of our students rise to a new hour from the Pacific coast, and within a few level of personal growth during their time here. hours of many state and national parks. Oxbow also offers a Summer Art Camp for The Oxbow semester is an intense explora- younger teens, which can be a wonderful tion of artistic inquiry combined with the stand-alone experience or an enriching way to rigorous academics necessary to complete prepare to spend a semester with us. high school on time and be well-prepared for 2 3 Mission “My semester at Oxbow transformed my life. I felt totally prepared for college, completely comfortable with myself, and fully able to tackle any challenges that were thrown at me. -

Matter DAY MAR25 CITI WANG THEATRE | MA STATE HOUSE

ARTS ADVOCACY matter DAY MAR25 CITI WANG THEATRE | MA STATE HOUSE Emcee: Joyce Kulhawik President, Boston Theater Critics’ Association Hosted by: Joe Spaulding President & CEO Citi Performing Arts Center Welcome • Sue Dahling Sullivan, Chief Strategic Officer, Citi Performing Arts Center • Rep. Cory Atkins, House Chair, Joint Committee on Tourism, Arts, and Cultural Development Prepping for Meetings with the Legislators • Sara Stackhouse, Executive Producer, Actors’ Shakespeare Project, MASSCreative • Lauren Wolk, Associate Director, Cultural Center of Cape Cod • Shanelle Chloe Villegas, Senior, Boston Arts Academy • Emily Ruddock, Director of the Downtown Lynn Cultural District Meeting with your Legislator • Matt Wilson, Executive Director, MASSCreative • Sen. Eric Lesser, Senate Chair, Joint Committee on Tourism, Arts, and Cultural Development • Vanessa Snow, Manager of Organizing and Policy Initiatives, Hyde Square Task Force Off to Beacon Hill • Julie Burros, Chief of Arts and Culture, Boston #Arts Matter March to State House Meetings with Legislators. Please report back to Room 511. Tweet before your meeting: Celebrating #ArtsMatter Advocacy Day w/ @MASSCreative & meeting w/ [legislator Twitter handle] to talk about arts & culture in my community! Thank you to our #ArtsMatter Advocacy Day Partners Actors' Shakespeare Project Coolidge Corner Theatre notloB Music Adams-Anthony Center Cotuit Center for the Arts Now and There AHA! New Bedford Cultural Center of Cape Cod Old South Meeting House American Textile History Cultural Organization -

How Are Boston Pilot School Students Faring? Student Demographics, Engagement, and Performance 1998-2003

How Are Boston Pilot School Students Faring? Student Demographics, Engagement, and Performance 1998-2003 Rosann Tung, Monique Ouimette, and Jay Feldman Presented at AERA, San Diego Center for Collaborative Education 1135 Tremont Street, Suite 490 Boston, MA 02120 March 2004 How Are Boston Pilot School Students Faring? Student Demographics, Engagement, and Performance 1998-2003 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ...........................................................................................................I INTRODUCTION......................................................................................................................... 1 FINDINGS..................................................................................................................................... 2 STUDENT DEMOGRAPHICS ........................................................................................................... 4 RACIAL DEMOGRAPHICS........................................................................................................ 4 OTHER DEMOGRAPHIC INFORMATION .................................................................................... 8 STUDENT ENGAGEMENT ............................................................................................................ 11 STUDENT ATTENDANCE ....................................................................................................... 12 STUDENT WAIT LIST ........................................................................................................... -

2002-House-02-January.Pdf (10.37Mb)

JOURNAL OF THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES OF (Etjc Commontoealtf) of itlassacijusctts 2002 PRINTED BY ORDER OF THE HOUSE AND IN ACCORDANCE WITH THE PROVISIONS OK SECTION 10 OF CHAPTER 5 OF THE GENERAL LAWS. BOSTON EAGLE GRAPHICS, INC., LEGISLATIVE PRINTERS 30 LANCASTER STREET 2002 LIST OF PERSONS ELECTED AS MEMBERS OF THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES FOR THE YEARS 2001-2002. D — Democrat R — Republican BARNSTABLE, DUKES AND NANTUCKET COUNTIES. Brewster 1 District Dennis, Precincts 1, 2, 4, 5 > Thomas N. George (R) of Yarmouth Yarmouth, Precincts 1. 2. 3. 4. 5 . I Barnstable, Precincts 1, 2, 3, 4. 5, 6, District 2 7, 8. 10. II Demetrius J. Atsalis (D) of Barnstable Sandwich, Precinct 4 Bourne, Precincts 3. 4, 5. 6 Falmouth, Precincts 3. 4, 7. 8 District 3 Mash pee Matthew C. Patrick (D) of Falmouth Sandwich, Precincts 5. 6. 7 Chatham Dennis, Precinct 3 Eastham Harwich Orleans . Shirley Gomes (R) of Harwich Provincetown Truro Wellfleet BARNSTABLE. DUKES AND NANTUCKET DISTRICT Barnstable (Barnstable Co.): Precinct 9 Falmouth (Barnstable Co.): Precincts 1. 2, 5. 6 Yarmouth (Barnstable Co.): Precinct 6 Aquinnah (Dukes Co.) . Chilmark (Dukes Co.) ^ Eric Turkington (D) of Falmouth. Edgartown (Dukes Co.) . Gosnold (Dukes Co.) Oak Bluffs (Dukes Co.) Tisbury (Dukes Co.) West Tisbury (Dukes Co.) . Nantucket (Nantucket Co.) BERKSHIRE COUNTY. Adams Clarksburg Florida North Adams Daniel E Bosley (D) of North Adams Savoy Williamstown BKRKSHIRK COUNT»' Concluded Bockel Cheshire Dal ton Hancock Hinsdale Lanes borough New -\shford . Peru Pittsfield: Ward I. Precinct B Richmond Washington Windsor \shfield (Franklin Co ) Shaun P Kelly (R) of Dallon Buckland (Franklin Co.) Charlemont (Franklin Co.) Haw ley ( Franklin Co ) Monroe (Franklin Co.) Rowe (Franklin Co.) Shelburne (Franklin Co.) Chester (Hampden Co.) Cummington (Hampshire Co.) Goshen (Hampshire Co.) Huntington (Hampshire Co.) Middlefield (Hampshire Co.) Plainfield (Hampshire Co.) Pittsfield: District 3 Ward 1. -

JIMENA BERMEJO [email protected] •

JIMENA BERMEJO [email protected] • www.jimenabermejo.com CHOREOGRAPHY Car Ride, Somerville Arts Council Grant award, Somerville, MA 2017 (Em) brace; or what my cell phone has a tendency to do to me, (Anthony Green Composer), Judson Church, Manhattan, NY 2017 The Wall Has Been Built, Dance Complex, Cambridge, MA 2016 Mine, Yours, Our, Mobius @ Green St, Green Street Studios, Cambridge, MA 2016 The Concert for the Moon/Equinox Music Festival, Berklee College of Music Duet for Trombone and Dancer, Boston Conservatory, Boston, MA 2016 Guest choreographer for Dances at Noon at Tufts University, Medford, MA 2016 Four Square performance at Green Street Studios, Cambridge , MA 2016 Mix tape, Open Work Show at Dance Complex, Cambridge, MA 2015 Memorandome,(in collaboration with Alissa Cardone), Somerville Art Beat Festival, MA 2015 Bad Math, She was, College of The Holy Cross (Guest Artist), Worcester, MA 2015 Benatar, Then, again…, And again… Somerville Arts Fest, MA, 2012, Art Beat Festival 2013 Monster, Emerging Artists Concert, Cambridge, MA, and Gowanous Guest Room, Brooklyn, NY 2008 On The Down Low, Emerging Artists Concert, Cambridge, MA 2008 Scavengers, guest choreographer Cambridge Ringe and Latin High School, Cambridge, MA 2007 Come To Your Senses: An Experience of Vision, choreographer and co-director, Cambridge, MA 2006 Foam, Performance Works Project (2nd session), co-producer and choreographer, Cambridge, MA 2006 Short Stories, co-producer and choreographer, Cambridge, MA 2005 Falling to Solid Ground, co-producer and choreographer, Cambridge, MA 2006 Xixax, in collaboration with Nicole Pierce, Somerville Theater, Somerville, MA 2004 Apples and Pairs, co-producer and choreographer, Cambridge, MA 1999 An Evening of Love, choreographer.