Abstract Rewriting Spinsterhood

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Donahue Poetry Collection Prints 2013.004

Donahue Poetry Collection Prints 2013.004 Quantity: 3 record boxes, 2 flat boxes Access: Open to research Acquisition: Various dates. See Administrative Note. Processed by: Abigail Stambach, June 2013. Revised April 2015 and May 2015 Administrative Note: The prints found in this collection were bought with funds from the Carol Ann Donahue Memorial Poetry endowment. They were purchased at various times since the 1970s and are cataloged individually. In May 2013, it was transferred to the Sage Colleges Archives and Special Collections. At this time, the collection was rehoused in new archival boxes and folders. The collection is arranged in call number order. Box and Folder Listing: Box Folder Folder Contents Number Number Control Folder 1 1 ML410 .S196 C9: Sports et divertissements by Erik Satie 1 2 N620 G8: Word and Image [Exhibition] December 1965, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum 1 3 N6494 .D3 H8: Dada Manifesto 1949 by Richard Huelsenbeck 1 4 N6769 .G3 A32: Kingling by Ian Gardner 1 5 N7153 .T45 A3 1978X: Drummer by Andre Thomkins 1 6 NC790 .B3: Landscape of St. Ives, Huntingdonshire by Stephen Bann 1 7 NC1820 .R6: Robert Bly Poetry Reading, Unicorn Bookshop, Friday, April 21, 8pm 1 8 NC1850 .P28 P3 V.1: PN2 Experiment 1 9 NC1850 .P28 P3 V.2: PN2 Experiment 1 10 NC1850 .P28 P3 V.4: PN2 Experiment 1 11 NC1850 .P28 P3 V.5: PN2 Experiment 1 12 NC1850 .P28 P3 V.6: PN2 Experiment 1 13 NC1850 .P28 P3 V.7: PN2 Experiment 1 14 NC1850 .P28 P3 V.9: PN2 Experiment 1 15 NC1850 .P28 P3 V.10: PN2 Experiment 1 16 NC1850 .P28 P3 V.12: PN2 Experiment 1 17 NC1850 .P28 P3 V.13: PN2 Experiment 1 18 NC1860 .N4: Peace Post Card no. -

How Second-Wave Feminism Forgot the Single Woman Rachel F

Hofstra Law Review Volume 33 | Issue 1 Article 5 2004 How Second-Wave Feminism Forgot the Single Woman Rachel F. Moran Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarlycommons.law.hofstra.edu/hlr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Moran, Rachel F. (2004) "How Second-Wave Feminism Forgot the Single Woman," Hofstra Law Review: Vol. 33: Iss. 1, Article 5. Available at: http://scholarlycommons.law.hofstra.edu/hlr/vol33/iss1/5 This document is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarly Commons at Hofstra Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Hofstra Law Review by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons at Hofstra Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Moran: How Second-Wave Feminism Forgot the Single Woman HOW SECOND-WAVE FEMINISM FORGOT THE SINGLE WOMAN Rachel F. Moran* I cannot imagine a feminist evolution leading to radicalchange in the private/politicalrealm of gender that is not rooted in the conviction that all women's lives are important, that the lives of men cannot be understoodby burying the lives of women; and that to make visible the full meaning of women's experience, to reinterpretknowledge in terms of that experience, is now the most important task of thinking.1 America has always been a very married country. From early colonial times until quite recently, rates of marriage in our nation have been high-higher in fact than in Britain and western Europe.2 Only in 1960 did this pattern begin to change as American men and women married later or perhaps not at all.3 Because of the dominance of marriage in this country, permanently single people-whether male or female-have been not just statistical oddities but social conundrums. -

Title "Stand by Your Man/There Ain't No Future In

TITLE "STAND BY YOUR MAN/THERE AIN'T NO FUTURE IN THIS" THREE DECADES OF ROMANCE IN COUNTRY MUSIC by S. DIANE WILLIAMS Presented to the American Culture Faculty at the University of Michigan-Flint in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Liberal Studies in American Culture Date 98 8AUGUST 15 988AUGUST Firs t Reader Second Reader "STAND BY YOUR MAN/THERE AIN'T NO FUTURE IN THIS" THREE DECADES OF ROMANCE IN COUNTRY MUSIC S. DIANE WILLIAMS AUGUST 15, 19SB TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface Introduction - "You Never Called Me By My Name" Page 1 Chapter 1 — "Would Jesus Wear A Rolen" Page 13 Chapter 2 - "You Ain’t Woman Enough To Take My Man./ Stand By Your Man"; Lorrtta Lynn and Tammy Wynette Page 38 Chapter 3 - "Think About Love/Happy Birthday Dear Heartache"; Dolly Parton and Barbara Mandrell Page 53 Chapter 4 - "Do Me With Love/Love Will Find Its Way To You"; Janie Frickie and Reba McEntire F'aqe 70 Chapter 5 - "Hello, Dari in"; Conpempory Male Vocalists Page 90 Conclusion - "If 017 Hank Could Only See Us Now" Page 117 Appendix A - Comparison Of Billboard Chart F'osi t i ons Appendix B - Country Music Industry Awards Appendix C - Index of Songs Works Consulted PREFACE I grew up just outside of Flint, Michigan, not a place generally considered the huh of country music activity. One of the many misconception about country music is that its audience is strictly southern and rural; my northern urban working class family listened exclusively to country music. As a teenager I was was more interested in Motown than Nashville, but by the time I reached my early thirties I had became a serious country music fan. -

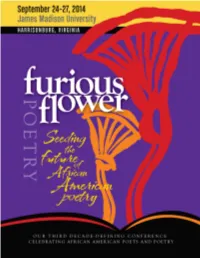

Furiousflower2014 Program.Pdf

Dedication “We are each other’s harvest; we are each other’s business; we are each other’s magnitude and bond.” • GWENDOLYN BROOKS Dedicated to the memory of these poets whose spirit lives on: Ai Margaret Walker Alexander Maya Angelou Alvin Aubert Amiri Baraka Gwendolyn Brooks Lucille Clifton Wanda Coleman Jayne Cortez June Jordan Raymond Patterson Lorenzo Thomas Sherley Anne Williams And to Rita Dove, who has sharpened love in the service of myth. “Fact is, the invention of women under siege has been to sharpen love in the service of myth. If you can’t be free, be a mystery.” • RITA DOVE Program design by RobertMottDesigns.com GALLERY OPENING AND RECEPTION • DUKE HALL Events & Exhibits Special Time collapses as Nigerian artist Wole Lagunju merges images from the Victorian era with Yoruba Gelede to create intriguing paintings, and pop culture becomes bedfellows with archetypal imagery in his kaleidoscopic works. Such genre bending speaks to the notions of identity, gender, power, and difference. It also generates conversations about multicultur- alism, globalization, and transcultural ethos. Meet the artist and view the work during the Furious Flower reception at the Duke Hall Gallery on Wednesday, September 24 at 6 p.m. The exhibit is ongoing throughout the conference, 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. FUSION: POETRY VOICED IN CHORAL SONG FORBES CENTER FOR THE PERFORMING ARTS Our opening night concert features solos by soprano Aurelia Williams and performances by the choirs of Morgan State University (Eric Conway, director) and James Madison University (Jo-Anne van der Vat-Chromy, director). In it, composer and pianist Randy Klein presents his original music based on the poetry of Margaret Walker, Michael Harper, and Yusef Komunyakaa. -

American Book Awards 2004

BEFORE COLUMBUS FOUNDATION PRESENTS THE AMERICAN BOOK AWARDS 2004 America was intended to be a place where freedom from discrimination was the means by which equality was achieved. Today, American culture THE is the most diverse ever on the face of this earth. Recognizing literary excel- lence demands a panoramic perspective. A narrow view strictly to the mainstream ignores all the tributaries that feed it. American literature is AMERICAN not one tradition but all traditions. From those who have been here for thousands of years to the most recent immigrants, we are all contributing to American culture. We are all being translated into a new language. BOOK Everyone should know by now that Columbus did not “discover” America. Rather, we are all still discovering America—and we must continue to do AWARDS so. The Before Columbus Foundation was founded in 1976 as a nonprofit educational and service organization dedicated to the promotion and dissemination of contemporary American multicultural literature. The goals of BCF are to provide recognition and a wider audience for the wealth of cultural and ethnic diversity that constitutes American writing. BCF has always employed the term “multicultural” not as a description of an aspect of American literature, but as a definition of all American litera- ture. BCF believes that the ingredients of America’s so-called “melting pot” are not only distinct, but integral to the unique constitution of American Culture—the whole comprises the parts. In 1978, the Board of Directors of BCF (authors, editors, and publishers representing the multicultural diversity of American Literature) decided that one of its programs should be a book award that would, for the first time, respect and honor excellence in American literature without restric- tion or bias with regard to race, sex, creed, cultural origin, size of press or ad budget, or even genre. -

Cassette Books, CMLS,P.O

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 319 210 EC 230 900 TITLE Cassette ,looks. INSTITUTION Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. National Library Service for the Blind and Physically Handicapped. PUB DATE 8E) NOTE 422p. AVAILABLE FROMCassette Books, CMLS,P.O. Box 9150, M(tabourne, FL 32902-9150. PUB TYPE Reference Materials Directories/Catalogs (132) --- Reference Materials Bibliographies (131) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC17 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Adults; *Audiotape Recordings; *Blindness; Books; *Physical Disabilities; Secondary Education; *Talking Books ABSTRACT This catalog lists cassette books produced by the National Library Service for the Blind and Physically Handicapped during 1989. Books are listed alphabetically within subject categories ander nonfiction and fiction headings. Nonfiction categories include: animals and wildlife, the arts, bestsellers, biography, blindness and physical handicaps, business andeconomics, career and job training, communication arts, consumerism, cooking and food, crime, diet and nutrition, education, government and politics, hobbies, humor, journalism and the media, literature, marriage and family, medicine and health, music, occult, philosophy, poetry, psychology, religion and inspiration, science and technology, social science, space, sports and recreation, stage and screen, traveland adventure, United States history, war, the West, women, and world history. Fiction categories includer adventure, bestsellers, classics, contemporary fiction, detective and mystery, espionage, family, fantasy, gothic, historical fiction, -

Searching for the True Women's Writing

"SPLITTING OPEN THE WORLD" - SEARCHING FOR THE TRUE WOMEN'S WRITING BY JENNIFER DONOVAN A thesis submitted in part fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts (Honours). Department of Sociology University of New South Wales February, 1991 SYNOPSIS This thesis explores the contention presented by the so-called French feminists (including Irigaray, Kristeva, and especially Cixous) that the situation of women cannot change until they have their own discourse and that women's writing must be based in their bodies. The purpose of "l'ecriture feminine", these writers claim, 1s to inscribe difference, to awaken women to one another, and to undermine patriarchy. My ambition was to find actual examples of this "ecriture feminine", and evidence of its effects. In attempting to deal with the abstruseness of much of the writing by the French women who encourage women to celebrate the difference and "write the body", I have briefly indicated some points of contact and divergence between Anglo-American feminists and the French. I have also described the persistent patriarchal obstruction to women's writing in order to highlight the revolutionary potential of writing the body. I examined writing by women who were variously woman identified, feminist and anti-feminist. I also considered various styles of women's writing, particularly poetry, which seemed to approach most closely the discourse envisaged by the French theorists. The writers discussed include Tillie Olsen, Marge Piercy, Christina Stead, Adrienne Rich, Mary Daly, Susan Griffin and others. ACKNOWIEDGEMENTS This thesis owes its existence to the energies of many people other than just the author. -

Wendy Martin CV 2019-09.Pages

Professor Wendy Martin Department of English The Claremont Graduate University Claremont, California 91711 Curriculum Vita Higher Education University of California, Berkeley 1958-62 B.A. English and American Literature, 1962 University of California, Davis 1962-68 Ph.D American Literature (Specialization in Early American Literature), 1968 Dissertation topic: “The Chevalier and the Charlatan: A Study of Hugh Henry Brackenridge's Modern Chivalry” Academic Positions University of California, Davis 1964-66 Teaching Assistant 1966-68 Teaching Associate Queens College, C.U.N.Y. 1968-76 Assistant Professor 1976-84 Associate Professor 1984-87 Professor Stanford University 1973-74 Visiting Associate Professor 1977 Visiting Associate Professor (Summer) (Taught a Faculty Seminar for the Lilly Faculty Renewal Program) University of North Carolina, 1981 (Spring) Visiting Associate Professor Chapel Hill University of California, Davis 1984-85 (Fall/ Visiting Professor Winter) University of California, 1985-87 Visiting Professor Los Angeles Claremont Graduate University 1987 (Spring) Visiting Professor 1987-present Professor 1988-1999; Chair, Department of English 2003-2010; 2018-2019; 2019 (Fall) 1996-1999 Chair, Faculty Executive Committee Wendy Martin Page !2 2005-2006 Director, Transdisciplinary Studies 2006-2008 Associate Provost and Director, Transdisciplinary Studies 2008-2013 Vice-Provost and Director, Transdisciplinary Studies 2010-2015 Director, Kingsley and Kate Tufts Poetry Awards Wendy Martin Page !3 Professional Activities Administrative Experience Coordinator of the American Studies Program, Queens College, 1972-76. Coordinator of the Women's Studies Program, Queens College, 1973-83. Chair, Department of English, Claremont Graduate University, 1988-99; Fall 2003-Spring 2010. Co-director, American Studies Program, Claremont Graduate University, 1988- . Director, Summer Institute for Young Professionals, 1991. -

Lesbian Lives and Rights in Chatelaine

From No Go to No Logo: Lesbian Lives and Rights in Chatelaine Barbara M. Freeman Carleton University Abstract: This study is a feminist cultural and critical analysis of articles about lesbians and their rights that appeared in Chatelaine magazine between 1966 and 2004. It explores the historical progression of their media representation, from an era when lesbians were pitied and barely tolerated, through a period when their struggles for their legal rights became paramount, to the turn of the present cen- tury when they were displaced by post-modern fashion statements about the “flu- idity” of sexual orientation, and stripped of their identity politics. These shifts in media representation have had as much to do with marketing the magazine as with its liberal editors’ attempts to deal with lesbian lives and rights in ways that would appeal to readers. At the heart of this overview is a challenge to both the media and academia to reclaim lesbians in all their diversity in their real histori- cal and contemporary contexts. Résumé : Cette étude propose une analyse critique et culturelle féministe d’ar- ticles publiés dans le magazine Châtelaine entre 1966 et 2004, qui traitent des droits des lesbiennes. Elle explore l’évolution historique de leur représentation dans les médias, de l’époque où les lesbiennes étaient tout juste tolérées, à une période où leur lutte pour leurs droits légaux devint prépondérante, jusqu’au tournant de ce siècle où elles ont été dépouillées de leur politique identitaire et « déplacées » par des éditoriaux postmodernes de la mode sur la « fluidité » de leur orientation sexuelle. -

ITALIAN AMERICAN FEMALE AUTOBIOGRAPHY by Marta Piroli the Central Point of This Thesis Is the Recogniti

ABSTRACT FINDING VOICES: ITALIAN AMERICAN FEMALE AUTOBIOGRAPHY by Marta Piroli The central point of this thesis is the recognition and exploration of the tradition of female Italian American autobiography, focusing on the choice of some Italian American writers to camouflage their Italian background and change their name. The thesis consists of four chapters. The first chapter explores a brief history of Italian migration in America during the nineteenth century. The second part of this chapter provides a literary discussion about the most important autobiographical theories over the twentieth century, focusing on the female self. The second chapter explores the role of Italian woman in Italian culture, and the first steps of emancipation of the children of the Italian immigrants. The third chapter will offer an approach to autobiography as a genre for expressing one’s self. The final chapter provides an analysis of significant Italian American women writers and their personal search for identity. FINDING VOICES: ITALIAN AMERICAN FEMALE AUTOBIOGRAPHY A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Miami University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of English by Marta Piroli Miami University Oxford, Ohio 2006 Advisor____________________________ Gwendolyn Etter-Lewis Reader_____________________________ Cheryl Heckler Reader_____________________________ Sante Matteo CONTENTS Chapter I: Italian Immigration An Overview 1 1. Italian Migration in America 2 2. Claiming an Italian American Tradition 8 3. Claiming a Theoretical Tradition: Ego Psychology 10 4. The Language of the Subject 13 5. Contextualizing the Subject 14 6. Multiple Subjects: Race and Ethnicity 15 7. Conclusion 17 Chapter II: Italian Life in America 18 Chapter III: Autobiography As Exploration of The Self 31 8. -

Sanders, Geterly Women Inamerican History:,A Series. Pook Four, Woien

DOCONIMM RIBOSE ED 186 Ilk 3 SO012596 AUTHOR Sanders, geTerly TITLE Women inAmerican History:,A Series. pook Four,Woien in the Progressive Era 1890-1920.. INSTITUTION American Federation of Teachers, *Washington, D.C. SPONS AGENCY Office,of Education (DHEW), Wastington, D.C. Wolen's Educational Egutty Act Program. PUB DATE 79 NOTE 95p.: For related documents, see SO 012 593-595. AVAILABLE FROM Education Development Center, 55 Chapel Street, Newton, MA 02160 (S2.00 plus $1.30 shipping charge) EDRS gRICE MF01 Plus Postige. PC Not.Available from EDRS. DESCRIPTORS Artists; Authors: *CiVil Rights: *Females; Feminksm; Industrialization: Learning Activities: Organizations (Groups): Secondary Education: Sex Discrioination; *Sex Role: *Social Action: Social Studies;Unions; *United States History: Voting Rights: *Womens Studies ABSTRACT 'The documente one in a series of four on.women in American history, discusses the rcle cf women in the Progressive Era (11390-1920)4 Designed to supplement high school U.S.*history. textbooks; the book is co/mprised of five chapter's. Chapter I. 'describes vtormers and radicals including Jane A3damsand Lillian Wald whs b4tan the settlement house movement:Florence Kelley, who fought for labor legislation:-and Emma Goldmanand Kate RAchards speaking against World War ft Of"Hare who,became pOlitical priscners for I. Chapter III focuses on women in factory workand the labor movement. Excerpts from- diaries reflectthe'work*ng contlitions in factor4es which led to women's ipvolvement in the,AFL andthe tormatton of the National.Wcmenls Trade Union League. Mother Jones, the-Industrial Workers of the World, and the "Bread and Roses"strike (1S12) of 25,000 textile workers in Massachusetts arealso described. -

Louisa S. Mccord and the "Feminist" Debate Cindy A

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2011 Louisa S. Mccord and the "Feminist" Debate Cindy A. McLeod Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES LOUISA S. MCCORD AND THE “FEMINIST” DEBATE By CINDY A. McLEOD A Dissertation submitted to the Program of Interdisciplinary Humanities in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree Awarded: Summer Semester, 2011 The members of the committee approve the dissertation of Cindy A. McLeod defended on June 8, 2011 Maxine D. Jones Professor Directing Dissertation Maxine Montgomery University Representative Jennifer Koslow Committee Member Charles Upchurch Committee Member Approved: John Kelsay, Chair, Program in Interdisciplinary Humanities Joseph Travis, Dean, College of Arts and Sciences The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members. ii I dedicate this to my best friend and understanding husband, Lee Henderson. You’ll be in my heart, forever. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to acknowledge the professors whose influence this work illustrates: Dr. Maxine Jones, Dr. Jennifer Koslow, Dr. Charles Upchurch, Dr. Maxine Montgomery, Dr. Bill Cloonan, Dr. Ray Fleming, Dr. Leon Golden, Dr. Jean Bryant, Dr. Elna Green, Dr. Eugene Crook, Dr. David Johnson, Dr. Jim Crooks, Dr. Dale Clifford, Dr. Daniel Schaefer, Prof. Joe Sasser and Dr. Maricarmen Martinez. Thank you for training my mind that I might become a critical thinker. Sapere Aude! (Dare to Know!) iv TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF TABLES .........................................................................................................