Progress of Trachoma Mapping in Mainland Tanzania: Results of Baseline Surveys from 2012 to 2014 Upendo J

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Prevalence of Wuchereria Bancrofti Infection in Mosquitoes from Pangani District, Northeastern Tanzania Godlisten S

ORIGINAL ARTICLE Prevalence of Wuchereria bancrofti Infection in Mosquitoes from Pangani District, Northeastern Tanzania Godlisten S. Materua aNational Institute for Medical Research, Tukuyu Research Centre, Mbeya, Tanzania Correspondence to Godlisten S. Materu ([email protected]) ABSTRACT Background: Wuchereria bancrofti is the most widely distributed of the 3 nematodes known to cause lymphatic filariasis, the other 2 being Brugia malayi and Brugia timori. Anopheles gambiae and Anopheles funestus are the main vectors. However, the relative contributions of mosquito vectors to disease burden and infectivity are becoming increasingly important in coastal East Africa, and this is particularly true in the urban and semiurban areas of Pangani District, Tanzania. Methods: Mosquitoes were sampled from 5 randomly selected villages of Pangani District, namely, Bweni, Madanga, Meka, Msaraza, and Pangani West. Sampling of mosquitoes was done using standard Centers for Disease Control light traps with incandescent light bulbs. The presence of W. bancrofti in mosquitoes was determined via polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assays using NV1 and NV2 primers, and PoolScreen 2 software was used to determine the estimated rate of W. bancrofti infection in mosquitoes. Results: A total of 951 mosquitoes were collected, of which 99.36% were Culex quinquefasciatus, 0.32% were Anopheles gambiae, and 0.32% other Culex species. The estimated rate of W. bancrofti infection among these mosquitoes was 3.3%. Conclusion: This was the first study employing the use of PoolScreen PCR to detectW. bancrofti circulating in mosquito vectors in Pangani District, northeastern Tanzania. The presence of W. bancrofti infection suggests the possibility of infected humans in the area. The high abundance of Cx. -

3069 Muheza District Council 5003 Internal Audit 5004 Admin and HRM 5005 Trade and Economy 5006 Administration and Adult Education 5007 Primary Education

Council Subvote Index 86 Tanga Region Subvote Description Council District Councils Number Code 2018 Tanga City Council 5003 Internal Audit 5004 Admin and HRM 5005 Trade and Economy 5006 Administration and Adult Education 5007 Primary Education 5008 Secondary Education 5009 Land Development & Urban Planning 5010 Health Services 5011 Preventive Services 5012 Health Centres 5013 Dispensaries 5014 Works 5018 Urban Water Supply 5022 Natural Resources 5027 Community Development, Gender & Children 5031 Salaries for VEOs 5032 Salaries for MEOs 5033 Agriculture 5034 Livestock 5036 Environments 2025 Korogwe Town Council 5003 Internal Audit 5004 Admin and HRM 5005 Trade and Economy 5006 Administration and Adult Education 5007 Primary Education 5008 Secondary Education 5009 Land Development & Urban Planning 5010 Health Services 5011 Preventive Services 5012 Health Centres 5013 Dispensaries 5014 Works 5018 Urban Water Supply 5022 Natural Resources 5027 Community Development, Gender & Children 5031 Salaries for VEOs 5032 Salaries for MEOs 5033 Agriculture 5034 Livestock 5036 Environments 3069 Muheza District Council 5003 Internal Audit 5004 Admin and HRM 5005 Trade and Economy 5006 Administration and Adult Education 5007 Primary Education ii Council Subvote Index 86 Tanga Region Subvote Description Council District Councils Number Code 3069 Muheza District Council 5008 Secondary Education 5009 Land Development & Urban Planning 5010 Health Services 5011 Preventive Services 5012 Health Centres 5013 Dispensaries 5014 Works 5017 Rural Water Supply 5022 -

Pangani Basin: a Situation Analysis

Pangani Basin: A Situation Analysis IUCN Eastern Africa Programme 2003 i Published by: Copyright: © 2003 International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources This publication may be produced in whole or part and in any form for education or non-profit uses, without special permission from the copyright holder, provided acknowledgement of the source is made. IUCN would appreciate receiving a copy of any publication which uses this publication as a source. No use of this publication may be made for resale or other commercial purpose without the prior written permission of IUCN. Citation: IUCN Eastern Africa Programme, 2003. The Pangani River Basin: A Situation Analysis, xvi + 104pp. ISBN: 2-8317-0760-9 Design and layout: Gordon O. Arara Printed by: ScanHouse Press Ltd. Photo 1: The summit of Mount Kilimanjaro; Photo 2: Forest stand at 1 Shire Njoro; Photo 3: Gate controlling the release of water into irrigation furrows; Photo 4: Children swimming in an irrigation 3 4 reservoir; Photo 5: Sisal plantations; Photo 6: Irrigated rice scheme; 2 Photo 7: Water gauging station at Chemka Spring; Photo 8: Vandalized gate controlling the release of water into irrigation furrows; Photo 9: 5 Dam wall at Nyumba ya Mungu Reservoir (color changes mark the declining water levels); Photo 10: A vendor sells water from a borehole 6 9 10 Photos 1, 3, 5, 6, 8, 9 copyright 2003 Kelly West; Photos 2, 7 7 8 copyright 2002 Kim Geheb; Photos 4, 10 copyright 2003 Ger Bergkamp. Available from: IUCN- EARO Publications Service Unit, P. O. Box 68200 - 00200, Nairobi, Kenya; Telephone ++ 254 20 890605-12; Fax ++ 254 20 890615; E-mail: [email protected] The designations of geographical entities in this book, and the presentation of the material, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the participating organiza- tions concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or of its authorities, or con- cerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. -

Tanga Coastal Zone Conservation and Development Programme

Tanga Coastal Zone Conservation and Development Programme End of Phase III Evaluation EARO/75969/801 I PREFACE “Behold! In the creation of the heavens and the earth; in the alteration of the Night and the Day; in the sailing of the ships through the Ocean for the profit of mankind; in the rain which He sends down from the skies, and the life which He gives therewith to an earth that is dead; in the beasts of all kinds that He scatters though the earth, in the change of the winds, and the clouds which they trail like their slaves between the sky and the earth; - here indeed are signs for a people who are wise”. Sura 2 aya 164 II ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The Evaluators would like to thank all those involved in the Evaluation Process and listed in Appendix 1. The Evaluation Team also appreciates the comments received on the draft of this report from the Districts, the SU, IUCN and Ireland Aid. Thanks are due to Dr Eric Verheij, Technical Advisor, Mr Solomon Makoloweka Regional Coastal Management Facilitator and the Staff of the support Unit for their support of the evaluation process. We should also like to make note of those Community members who made time to participate in the Village level meetings. Apologies are also due to Communities that were kept waiting due to over runs in the schedule for earlier meetings. Finally thanks are due to Government at National, Regional and District level particularly to DEDs, DNROs and DCs from Pangani and Muheza Districts and Tanga Municipality. -

A Contextual Analysis for Village Land Use Planning in Tanzania's

A contextual analysis for village land use planning in Tanzania’s Bagamoyo and Chalinze districts, Pwani region and Mvomero and Kilosa districts, Morogoro region Sustainable Rangeland Management Project ILRI PROJECT REPORT ISBN: 92-9146-586-0 The International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI) works to improve food and nutritional security and reduce poverty in developing countries through research for efficient, safe and sustainable use of livestock. Co-hosted by Kenya and Ethiopia, it has regional or country offices and projects in East, South and Southeast Asia as well as Central, East, Southern and West Africa. ilri.org CGIAR is a global agricultural research partnership for a food-secure future. Its research is carried out by 15 research centres in collaboration with hundreds of partner organizations. cgiar.org A contextual analysis for village land use planning in Pwani and Morogoro regions of Tanzania i ii A contextual analysis for village land use planning in Pwani and Morogoro regions of Tanzania A contextual analysis for village land use planning in Tanzania’s Bagamoyo and Chalinze districts, Pwani region and Mvomero and Kilosa districts, Morogoro region Sustainable Rangeland Management Project Emmanuel Sulle and Wilbard Mkama Editor: Fiona Flintan (International Livestock Research Institute) July 2019 A contextual analysis for village land use planning in Pwani and Morogoro regions of Tanzania iii ©2019 International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI) ILRI thanks all donors and organizations which globally support its work through their contributions to the CGIAR Trust Fund This publication is copyrighted by the International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI). It is licensed for use under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International Licence. -

Coastal Profile for Tanzania Mainland 2014 District Volume II Including Threats Prioritisation

Coastal Profile for Tanzania Mainland 2014 District Volume II Including Threats Prioritisation Investment Prioritisation for Resilient Livelihoods and Ecosystems in Coastal Zones of Tanzania List of Contents List of Contents ......................................................................................................................................... ii List of Tables ............................................................................................................................................. x List of Figures ......................................................................................................................................... xiii Acronyms ............................................................................................................................................... xiv Table of Units ....................................................................................................................................... xviii 1. INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................... 19 Coastal Areas ...................................................................................................................................... 19 Vulnerable Areas under Pressure ..................................................................................................................... 19 Tanzania........................................................................................................................................................... -

Section Ii: Instructions to Bidders

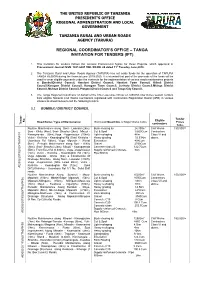

THE UNITED REPUBLIC OF TANZANIA PRESIDENT’S OFFICE REGIONAL ADMINISTRATION AND LOCAL GOVERNMENT TANZANIA RURAL AND URBAN ROADS AGENCY (TARURA) REGIONAL COORDINATOR’S OFFICE – TANGA INVITATION FOR TENDERS (IFT) . 1. This Invitation for tenders follows the General Procurement Notice for these Projects, which appeared in Procurement Journal ISSN: 1821-6021 VOL XII-NO. 24 dated 11th Tuesday June,2019. 2. The Tanzania Rural and Urban Roads Agency (TARURA) has set aside funds for the operation of TARURA TANGA REGION during the financial year 2019-2020. It is intended that part of the proceeds of the funds will be used to cover eligible payments under the contracts for the implementation of various roads maintenance projects at BumbuliDistrict Council, Handeni District Council, Handeni Town Council, Kilindi District Council,Korogwe District Council, Korogwe Town Council, Lushoto District Council,Mkinga District Council, Muheza District Council, Pangani District Council and Tanga City Council. 3. The Tanga Regional Coordinator on behalf of the Chief executive Officer of TARURA now invites sealed Tenders from eligible National Civil Works Contractors registered with Contractors Registration Board (CRB) in various classes as shown below to bid the following tenders. 3.1 BUMBULI DISTRICT COUNCIL Tender Eligible No. Road Name / Type of Maintenance Estimated Quantities of Major Works Items Prices Tender Tender contractors Tshs. Routine Maintenance along Soni - Lwandai (2km), Bush clearing by 24,300m2 Civil Works 150,000/= Soni - Kihitu (4km), Soni- Shashui (2km), Mbuzii - Cut & Spoil 9,600Cum Contractors Kwangwenda (6km),Vuga -Vugamission (10km), Light reshaping 4Km Class VI and Vulini - Kivilicha - Kwandoghoi Rd (5km) Kiviricha - Heavy grading 32.53Km above. -

ICM Action Planning Lessons Learned from the Tanga Coastal Zone

ICM Action Planning Lessons Learned from the Tanga Coastal Zone Conservation and Development Programme Proceedings of a Workshop held in Tanga, Tanzania August 21-23, 2000 Prepared by Elin Torell, James Tobey and Trudy Van Ingen University of Rhode Island’s Coastal Resources Center Tanga Coastal Zone Conservation and Development Programme Tanzania Coastal Management Partnership World Conservation Union United States Agency for International Development Irish Aid Table of Contents 1. Introduction 2. What is Action Planning for Integrated Coastal Management? 3. The Coastal Management Project Cycle 4. The Evolution of Action Planning in Tanga 5. Key Dimensions of Action Planning in the Tanga Programme A. Issue identification, problem analysis and action prioritisation B. Capacity building C. Adoption and linking plans to existing legal and institutional frameworks D. Monitoring and evaluation E. Sustaining support and participation over time 6. Contextual Barriers and Bridges to Action Planning 7. The Outcomes of Action Planning 8. Guidance for Future Action Planning A. Issue identification and analysis B. Preparation of the action plan C. Formal adoption and funding Appendix: Workshop Session Plan 2 Workshop Participants ICM Action Planning: Lessons Learned from the Tanga Coastal Zone Conservation and Development Programme Tanga, Tanzania August 21-23, 2000 Facilitators 1. Elin Torell, University of Rhode Island, Coastal Resources Center 2. Jim Tobey, University of Rhode Island, Coastal Resources Center 3. Trudi Van Ingen, Tanga Coastal Zone Conservation and Development Programme Tanga programme support staff 4. Solomon Makoloweka 5. Chris Horrill 6. Margreth Ndwela 7. Stella Salim District Government Staff 8. Emanuel Mgongo, Pangani District Coordinator 9. Fatuma Bahunde, Tanga Municipality Agricultural Officer 10. -

Tanga Lessons Latest

Putting Adaptive Management into Practice: Collaborative Coastal Management in Tanga, Northern Tanzania Edited by: Sue Wells, Solomon Makoloweka and Melita Samoilys Putting Adaptive Management into Practice: Collaborative Coastal Management in Tanga, Northern Tanzania Edited by: Sue Wells, Solomon Makoloweka and Melita Samoilys 2007 The designation of geographical entities in this book, and the presentation of the material, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of IUCN, Government of Tanzania or Irish Aid (IA) concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect those of IUCN, Government of Tanzania or Irish Aid (IA). This publication has been made possible by funding from Irish Aid (IA). Published by: Reproduction of this publication for educational or other non-commercial purposes is authorized without prior written permission from the copyright holder provided the source is fully acknowledged. Reproduction of this publication for resale or other commercial purposes is prohibited without prior written permission of the copyright holder. Citation: Sue Wells, Solomon Makoloweka and Melita Samoilys (2007): Putting Adaptive Management into Practice: Collaborative Coastal Management in Tanga, Northern Tanzania, x+ 197p. Photo credits: M. Dengo, M. Mayer, M. Podalan, M. Samoilys, E. Verheij, S. Wells and Tanga Coastal Zone Conservation and Development -

The Center for Research Libraries Scans to Provide Digital Delivery of Its Holdings. in the Center for Research Libraries Scans

The Center for Research Libraries scans to provide digital delivery of its holdings. In The Center for Research Libraries scans to provide digital delivery of its holdings. In some cases problems with the quality of the original document or microfilm reproduction may result in a lower quality scan, but it will be legible. In some cases pages may be damaged or missing. Files include OCR (machine searchable text) when the quality of the scan and the language or format of the text allows. If preferred, you may request a loan by contacting Center for Research Libraries through your Interlibrary Loan Office. Rights and usage Materials digitized by the Center for Research Libraries are intended for the personal educational and research use of students, scholars, and other researchers of the CRL member community. Copyrighted images and texts are not to be reproduced, displayed, distributed, broadcast, or downloaded for other purposes without the expressed, written permission of the Center for Research Libraries. © Center for Research Libraries Scan Date: December 27, 2007 Identifier: m-n-000128 fl7, THE UNITED REPUBLIC OF TANZANIA MINISTRY OF NATIONAL EDUCATION NATIONAL ARCHIVES DIVISION Guide to The Microfilms of Regional and District Books 1973 PRINTED BY THE GOVERNMENT PRINTER, DAR ES SALAAMs,-TANZANA. Price: S&. 6152 MINISTRY OF NATIONAL EDUCATION NATIONAL ARCHIVES DIVISION Guide to The Microfilms of Regional and District Books vn CONTENTS. Introduction ... .... ... ... ... History of Regional Administration .... ... District Books and their Subject Headings ... THE GUIDE: Arusha Region ... ... ... Coast Region ............... ... Dodoma Region .. ... ... ... Iringa Region ............... ... Kigoma ... ... ... ... ... Kilimanjaro Region .... .... .... ... Mara Region .... .... .... .... ... Mbeya Region ... ... ... ... Morogoro Region ... ... ... ... Mtwara Region ... ... Mwanza Region .. -

Appendices to Vol 4B

Vote 86 Tanga Region Councils in the Region Council District Councils Code 2018 Tanga City Council 2025 Korogwe Town Council 2038 Handeni Town Council 3069 Muheza District Council 3070 Pangani District Council 3071 Korogwe District Council 3072 Handeni District Council 3073 Lushoto District Council 3093 Kilindi District Council 3106 Mkinga District Council 3141 Bumbuli District Council 2 Vote 86 Tanga Region Council Development Budget Summary Local and Foreign 2014/15 Code Council Local Foreign Total 2018 Tanga City Council 6,284,528,000 4,055,726,000 10,340,254,000 2025 Korogwe Town Council 835,355,000 2,133,500,000 2,968,855,000 2038 Handeni Town Council 0 0 0 3069 Muheza District Council 1,724,971,000 2,109,900,000 3,834,871,000 3070 Pangani District Council 1,437,699,000 1,452,376,000 2,890,075,000 3071 Korogwe District Council 2,037,310,000 1,855,108,000 3,892,418,000 3072 Handeni District Council 2,584,232,000 2,273,114,000 4,857,346,000 3073 Lushoto District Council 3,092,479,000 2,451,378,000 5,543,857,000 3093 Kilindi District Council 3,223,981,000 1,940,690,000 5,164,671,000 3106 Mkinga District Council 1,878,651,000 1,255,017,000 3,133,668,000 3141 Bumbuli District Council 2,547,702,000 1,120,279,000 3,667,981,000 Total 25,646,908,000 20,647,088,000 46,293,996,000 3 Vote 86 Tanga Region Code Description 2012/2013 2013/2014 2014/2015 Actual Expenditure Approved Expenditure Estimates Local Foreign Local Foreign Local Foreign Total Shs. -

Northern Zone Regions Investment Opportunities

THE UNITED REPUBLIC OF TANZANIA PRIME MINISTER’S OFFICE REGIONAL ADMINISTRATION AND LOCAL GOVERNMENT Arusha “The centre for Tourism & Cultural heritage” NORTHERN ZONE REGIONS INVESTMENT OPPORTUNITIES Kilimanjaro “Home of the snow capped mountain” Manyara “Home of Tanzanite” Tanga “The land of Sisal” NORTHERN ZONE DISTRICTS MAP | P a g e i ACRONYMY AWF African Wildlife Foundation CBOs Community Based Organizations CCM Chama cha Mapinduzi DC District Council EPZ Export Processing Zone EPZA Export Processing Zone Authority GDP Gross Domestic Product IT Information Technology KTC Korogwe Town Council KUC Kilimanjaro Uchumi Company MKUKUTA Mkakati wa Kukuza Uchumi na Kupunguza Umaskini Tanzania NDC National Development Corporation NGOs Non Government Organizations NSGPR National Strategy for Growth and Poverty Reduction NSSF National Social Security Fund PANGADECO Pangani Development Corporation PPP Public Private Partnership TaCRI Tanzania Coffee Research Institute TAFIRI Tanzania Fisheries Research Institute TANROADS Tanzania National Roads Agency TAWIRI Tanzania Wildlife Research Institute WWf World Wildlife Fund | P a g e ii TABLE OF CONTENTS ACRONYMY ............................................................................................................ii TABLE OF CONTENTS ........................................................................................... iii 1.0 INTRODUCTION ..............................................................................................1 1.1 Food and cash crops............................................................................................1