The Reunion of a Great Camp: the Sagamore Amendment to the N.Y

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Carnegie Camp on Raquette Lake

Volume 16, 10, Number Number 2 2 Winter 2007–20082001-2002 NewsNews letter North Point: The Carnegie Camp on Raquette Lake ADIRONDACK ARCHITECTURAL HERITAGE The Carnegie Camp, North Point, Raquette Lake, c. 1905 (Rockefeller Family Collection) At the turn of the century, Raquette Lake, builder, and architect was unknown. Harvey one of the largest and most picturesque lakes Kaiser in his book Great Camps of the in the Adirondacks, was the site of several Adirondacks stated that, “The building plans large rustic camps designed by William West and execution of interior details suggest Durant. Less well known than Pine Knot and influences beyond the techniques of local Echo Camp is the Carnegie camp, designed craftsmen, although no record of the architect by Kirtland Kelsey Cutter and completed in exists.” Today its history, design, architect, 1903. and construction are thoroughly documented. Although the main buildings at Pine Knot Its history is as interesting as its architecture. and nearby Sagamore were influenced by The famous guide, Alvah Dunning, was the Swiss chalet architecture, the Carnegie camp first documented resident at North Point. He is more literally a Swiss chalet. There it settled here prior to 1865 and occupied a stands on the northern end of the lake, on a cabin originally built for hunters from slightly elevated plateau, commanding Albany. Another Albany resident, James Ten spectacular views. The land has been and still Eyck bought the land from the state after is known as North Point and the camp was Dunning issued him a quitclaim deed and built by Lucy Carnegie, the widow of constructed a modest hunting camp on the Andrew Carnegie’s younger brother Tom. -

Fall 13NL.Indd

Summer/Fall 2013 Volume 13, Number 2 Inside This Issue 2 From the Director’s Desk 2 Spotlight on History 3 Grant Unlocks Great Camps History 3 Carlson Tree Dedication 3 Teacher Training for Education Faculty 3 Snapping Turtle Makes an Apper- ance 3 The Metamorphosis At Camp Huntington Adirondack Trail Blazers Head To Cortland 4 Raquette Lake Champion 4 New Course Offered On Aug. 23, eight intrepid fi rst-year students completed SUNY Cortland’s inaugural version of a wilderness transition program, designed to prepare students mentally, physi- 4 Visitors From Abroad cally and psychologically for the challenges ahead in college. There are more than 260 such 5 Transcontinental Railway Reenacted programs around the country, and with Cortland’s extensive history with outdoor education, 5 Alumni Opportunities it is a natural fi t for our student body. 6 Nature Nook The Trail Blazers began their journey by moving into their campus accommodations the For Newsletter Extras previous Sunday and boarded vans for Raquette Lake. They were joined by Amy Shellman, assistant professor, recreation, parks and leisure studies, and Jen Miller ’08, M’12, adjunct cortland.edu/outdoor faculty, and two matriculating students, Olivia Joseph and Anthony Maggio. One of the under newsletter fi rst people they met upon their arrival at Camp Huntington was Ronnie Sternin Silver ’67, representing the Alumni Association board, who sponsored the opening pizza dinner for the Upcoming Events students. One of the objectives of Adirondack Trail Blazers (ATB) is to introduce incoming For a list of our Upcoming Events students to current students, faculty and alumni, so they’ll have some familiar faces to greet cortland.edu/outdoor them on campus and have a chance to ask questions about what life is like at Cortland. -

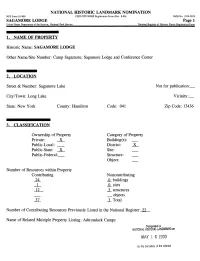

SAGAMORE LODGE Other Name/Site Number

NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARK NOMINATION NFS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 SAGAMORE LODGE Page 1 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 1. NAME OF PROPERTY Historic Name: SAGAMORE LODGE Other Name/Site Number: Camp Sagamore; Sagamore Lodge and Conference Center 2. LOCATION Street & Number: Sagamore Lake Not for publication:_ City/Town: Long Lake Vicinity:_ State: New York County: Hamilton Code: 041 Zip Code: 13436 3. CLASSIFICATION Ownership of Property Category of Property Private: X Building(s): __ Public-Local: __ District: X Public-State: X Site: __ Public-Federal: __ Structure: __ Object: __ Number of Resources within Property Contributing Noncontributing 24 0 buildings 1 0 sites 12 3 structures _ objects 37 3 Total Number of Contributing Resources Previously Listed in the National Register: 22 Name of Related Multiple Property Listing: Adirondack Camps Designated a NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARK on MAY 1 6 2000 by the Secratary of the Interior NFS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 SAGAMORE LODGE Page 2 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service__________________________________National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 4. STATE/FEDERAL AGENCY CERTIFICATION As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this __ nomination __ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. -

SUMMER 2019 NEWSLETTER Opening This Summer: ADKX Boathouse on Minnow Pond

THE EXCLUSIVE SUMMER GUIDE ISSUE! SUMMER 2019 NEWSLETTER Opening this summer: ADKX Boathouse on Minnow Pond. Enjoy a few hours on Minnow Pond from our new ADKX Boathouse. SUMMER 2019 PG 2 SUMMER 2019 PG 3 Two new exhibitions are sure to spark delight. Curious Creatures, a special—and quirky—exhibition features a monkey riding a goat, a school room filled with studious A WARM ADIRONDACK bunnies, smoking rabbits, and other unexpected examples WELCOME TO SUMMER 2019 of taxidermy such as a water FROM EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR DAVID KAHN AND bualo head and a python. All THE WHOLE TEAM AT ADKX are ornaments from Adirondack camps past and present. CURIOUS CREATURES Summer is here, and ADKX’s 2019 season o ers you and your family a wide range of exciting and uniquely Adirondack activities. Join us for a variety of new indoor and outdoor experiences for all ages! PRIVATE VIEWS Private Views, our other special Our new ADKX rustic boathouse opens on July 1, oering you exhibition for 2019, gives you the rare opportunity to cruise the waters of Minnow Pond in an the opportunity to see dozens antique guideboat, ski, or other Adirondack craft. And you can of iconic Adirondack landscape learn about the history of boating in the Adirondacks as you stroll paintings that are rarely if ever the scenic woodland trail leading from the ADKX campus publicly exhibited. to our boathouse. If you want to practice your rowing skills before heading out to the pond, our guideboat rowing interactive is available in our gigantic Life in the Adirondacks exhibition, along Rolling ‘Round the ‘Dacks is our new signature event on Saturday, August 17, with other fun hands-on activities. -

2018 Draft Amendment to the Blue Ridge Wilderness

BLUE RIDGE WILDERNESS Draft Amendment to the 2006 Blue Ridge Wilderness Unit Management Plan NYS DEC, REGION 5, DIVISION OF LANDS AND FORESTS 701 South Main St., Northville, NY 12134 [email protected] www.dec.ny.gov November 2018 Introduction The Blue Ridge Wilderness Area (BRWA) is located in the towns of Indian Lake, Long Lake, Arietta, and Lake Pleasant and the Village of Speculator within Hamilton County. The unit is 48,242 acres in size. A Unit Management Plan (UMP) for this area was completed in 2006. This UMP Amendment contains one proposal: Construction of the Seventh Lake Mountain – Sargent Ponds Multiple-Use Trail. Management Proposal Construction of the Seventh Lake Mountain – Sargent Ponds Multiple-Use Trail Background: During the planning efforts that led to the drafting and adoption of the Moose River Plains Wild Forest (MRPWF) UMP, it was realized that there is a great need for new, land-based snowmobile trail connections in the area. As a result, the 2011 MRPWF UMP put forth a conceptual proposal for a snowmobile trail leading eastward and north of MRPWF that would connect to the Sargent Ponds Wild Forest (SPWF) trail system—pending the adoption of a SPWF UMP. Ultimately, the Seventh Lake Mountain – Sargent Ponds Multiple-Use Trail will provide a land-based connection between the communities of Indian Lake, Raquette Lake, Inlet, and Long Lake. The proposed trail system will greatly reduce rider’s risk associated with lake crossings and traveling along and crossing major roads. Management Action: This UMP amendment proposes construction of a portion of the Seventh Lake Mountain – Sargent Ponds Multiple-Use Trail and its maintenance as a Class II Community Connector Trail. -

Two Camps on Osgood Pond

(1990) and co-author of another on Camp Santanoni (2000). In 1993, Kirschenbaum purchased Two camps White Pine Camp. Along with 22 other partners, he operated the camp first as a museum. Today, White Pine is a combi- nation rustic rental resort and ongoing historic preservation project, one that is on Osgood Pond likely to keep Kirschenbaum busy for years to come. PART ONE OF TWO White Pine Camp Words & pictures by LEE MANCHESTER Our tour started in the Caretaker’s Lake Placid News, July 21, 2006 Complex at White Pine Camp, where Kirschenbaum explained how the camp Last week, Adirondack Architec- from his “day job” as chairman of the had been built, and by whom, and tural Heritage offered tours of two Department of Counseling and Human when. camps on Osgood Pond, in Paul Development at the Warner School of In 1907, Adirondack hotelier Paul Smiths: White Pine Camp, and the University of Rochester, where he Smith was subdividing his vast hold- Northbrook Lodge. was known as one of the world’s lead- ings into camps for the well-to-do. New Architecturally distinct as the two ing authorities on the work of therapist York banker and businessman camps are from one another, they Carl Rogers. Archibald White and his much younger nonetheless have a great deal in common. In his off hours, Kirschenbaum has wife, Ziegfield Follies girl Olive Moore Both were built by the brilliant but built an equally distinguished career in White, bought 10 acres from Smith on a unschooled local contractor-cum-archi- historic preservation, first as the direc- point of Osgood Pond. -

Long Lake • Raquette Lake • Blue Mountain • Newcomb • Tupper Lake • Indian Lake

North Country Regional Economic Development Council Tourism Destination Area Nomination Workbook New York’s North Country Region North Country New York [TOURISM DESTINATION AREA NOMINATION WORKBOOK] Why is tourism important to the North Country? Tourism offers the most viable opportunity to diversity and ignite the North Country economy by capitalizing on existing demand to attract a wide variety of private investment that will transform communities. Tourism is already a $1 billion industry in the North Country and with its low upfront investment cost and quicker return on investment that many other industries, it is well- positioned to drive a new North Country economy as well as complement other strategic clusters of economic activity. Year-round tourism promotes a more sustainable, stable economy and more jobs; it’s the most likely growth industry for this region and will help recruit other types of investment. The region has a history of hospitality and several successful tourism hubs in place and exceptional four-season outdoor recreational opportunities are poised to leverage private investment in lodging, restaurant, attraction and other types of tourism related venues. Recognizing the transformative potential that tourism has in the North Country, the Regional Economic development Council is advancing the following strategies: Put tools in place to attract private investment in tourism which will drive demand to revitalize and diversity communities and create a climate that will allow entrepreneurs to flourish. Develop tourism infrastructure to transform the Region by driving community development and leveraging private investment in tourism destination area communities and corridors. The key to these strategies is that they recognize and focus attention on the need to attract and foster development in attractions, facilities and infrastructure conducive to attracting the 21st century traveling public. -

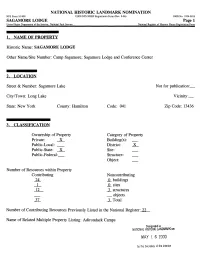

Historic Name: SAGAMORE LODGE Other Name/Site Number

NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARK NOMINATION NFS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 SAGAMORE LODGE Pagel United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 1. NAME OF PROPERTY Historic Name: SAGAMORE LODGE Other Name/Site Number: Camp Sagamore; Sagamore Lodge and Conference Center 2. LOCATION Street & Number: Sagamore Lake Not for publication: City/Town: Long Lake Vicinity:_ State: New York County: Hamilton Code: 041 Zip Code: 13436 3. CLASSIFICATION Ownership of Property Category of Property Private: X Building(s): __ Public-Local: __ District: X Public-State: X Site: __ Public-Federal:__ Structure: __ Object: __ Number of Resources within Property Contributing Noncontributing 24 0 buildings 1 0 sites 12 3 structures _ objects 37 3 Total Number of Contributing Resources Previously Listed in the National Register: 22 Name of Related Multiple Property Listing: Adirondack Camps Designated a NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARK on MAY 1 6 2000 by the Secratary of the Interior NFS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 SAGAMORE LODGE Page 2 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service__________________________________National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 4. STATE/FEDERAL AGENCY CERTIFICATION As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this __ nomination __ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. -

Mike Prescott: Field Notes, Topic Log, and Interview Transcript Raquette River Dams Oral History Project

Mike Prescott: Field Notes, Topic Log, and Interview Transcript Raquette River Dams Oral History Project Mike Prescott Field Notes Interview with Mike Prescott for the Raquette River Dams Oral History Project Collector: Camilla Ammirati (TAUNY) Recording Title: Mike Prescott (7.16.15) Format: Audio Digital Recording Length: 00:51:02 Machine Model used: Roland R-05 Wave/MP3 Recorder Interview date: July 16, 2015 Time: 1:30pm Place of interview: The TAUNY Center in Canton, NY Setting and Circumstance: Mike was glad to make a visit to Canton, so he met Roque Murray of WPBS and me at The TAUNY Center. We talked in the classroom, which made for a somewhat echo-y recording. Additional Notes: I first met Mike at the Raquette River Blueway Corridor group meeting the spring before I started on this project. He’s an Adirondack Guide and a historian of the river, and he has written a fair bit about the river’s history for the Adirondack Almanac. While he came to my attention as someone who shares our interest in the history of the dams rather than someone who was involved in or affected by their building, talking with him revealed his own personal connection to the dams’ history. As a child, he went to see the construction in progress, and it clearly stuck with him. He came back to the dams through his later interest in paddling and otherwise exploring the outdoors in the region. One particularly striking idea that came up in our discussion is that his main interest in the dams is, in a sense, an interest in the history of the dams that weren’t built. -

Wagner Vineyards

18_181829 bindex.qxp 11/14/07 11:59 AM Page 422 Index Albany Institute of History & Anthony Road Wine Company AAA (American Automobile Art, 276, 279 (Penn Yann), 317 Association), 34 Albany International Airport, Antique and Classic Boat Show AARP, 42 257–268 (Skaneateles), 355 Access-Able Travel Source, 41 Albany LatinFest, 280 Antique Boat Museum Accessible Journeys, 41 Albany-Rensselaer Rail Station, (Clayton), 383 Accommodations, 47 258 Antique Boat Show & Auction best, 5, 8–10 Albany Riverfront Jazz Festival, (Clayton), 30 Active vacations, 63–71 280 Antiques Adair Vineyards (New Paltz), Albany River Rats, 281 best places for, 12–13 229 Albright-Knox Art Gallery Canandaigua Lake, 336 Adirondack Balloon Festival (Buffalo), 396 Geneva, 348 (Glens Falls), 31 Alex Bay Go-Karts (near Thou- Hammondsport, 329 Adirondack Mountain Club sand Islands Bridge), 386 Long Island, 151–152, 159 (ADK), 69–71, 366 Alison Wines & Vineyards Lower Hudson Valley, 194 Adirondack Museum (Blue (Red Hook), 220 Margaretville, 246 Mountain Lake), 368 Allegany State Park, 405 Mid-Hudson Valley, 208 The Adirondacks Alternative Leisure Co. & Trips Rochester, 344 northern, 372–381 Unlimited, 40 Saratoga Springs, 267 southern, 364–372 Amagansett, 172, 179 Skaneateles, 355, 356 suggested itinerary, 56–58 America the Beautiful Access southeastern Catskill region, Adirondack Scenic Railroad, Pass, 40 231 375–376 America the Beautiful Senior Sullivan County, 252 African-American Family Day Pass, 42 Upper Hudson Valley, 219 (Albany), 280 American Airlines Vacations, 45 -

Inc. Chronology Management Team Carl

An Adirondack Chronology by The Adirondack Research Library of Protect the Adirondacks! Inc. Chronology Management Team Carl George Professor of Biology, Emeritus Department of Biology Union College Schenectady, NY 12308 [email protected] Richard E. Tucker Adirondack Research Library 897 St. David’s Lane Niskayuna, NY 12309 [email protected] Abbie Verner Archivist, Town of Long Lake P.O. Box 42 Long Lake, NY 12847 [email protected] Frank M. Wicks Associate Professor of Mechanical Engineering Union College Schenectady, NY 12308 [email protected] Last revised and enlarged – 25 March 2012 (No. 63) www.protectadks.org Adirondack Chronology 1 last revised 3/26/2012 Contents Page Adirondack Research Library 2 Introduction 2 Key References 4 Bibliography and Chronology 18 Special Acknowledgements 19 Abbreviations, Acronyms and Definitions 22 Adirondack Chronology – Event and Year 36 Needed dates 388 Adirondack Research Library The Adirondack Chronology is a useful resource for researchers and all others interested in the Adirondacks. This useful reference is made available by the Adirondack Research Library (ARL) committee of Protect the Adirondacks! Inc., most recently via the Schaffer Library of Union College, Schenectady, NY where the Adirondack Research Library has recently been placed on ‘permanent loan’ by PROTECT. Union College Schaffer Library makes the Adirondack Research Library collections available to the public as they has always been by appointment only (we are a non-lending ‘special research library’ in the grand scheme of things. See http://libguides.union.edu/content.php?pid=309126&sid=2531789. Our holdings can be searched It is hoped that the Adirondack Chronology may serve as a 'starter set' of basic information leading to more in- depth research. -

BUILDING on UPPER SARANAC LAKE a Guide to Using Natural Beauty and Traditional Adirondack Architecture to Your Greatest Advantage

BUILDING ON UPPER SARANAC LAKE A guide to using natural beauty and traditional Adirondack architecture to your greatest advantage. Origins of the Adirondack Style In the late 1870s, William West Durant, son of a railroad tycoon and the first Adirondack developer, built the first "Great Camp" on the shores of Raquette Lake. Camp Pine Knot was a collection of rustic dwellings that resembled European Swiss chalets, but with a primitive, naturalistic flavor that inspired a new architectural style. Durant was followed by William L. Coulter, who designed many camps, including Prospect Point (now Young Life), Eagle Island (now a Girl Scout Camp), and Moss Ledge, all on Upper Saranac Lake. Today, Great Camp innovations permeate the Adirondack building style. This brochure will guide buyers of undeveloped lots, and those who wish to renovate or add onto camps, as they join the historic building tradition of the Adirondacks and bring their own creativity to their future Great Camp. Three characteristics distinguished Adirondack camps: 1. Camp buildings were closely integrated with the landscape 2. Each camp had a distinctive compound plan with separate buildings for separate functions 3. Camps represented the first and fullest application of a rustic aesthetic in America Start with a Tour of the Lake by Water Adirondack architecture strives to harmonize with the surrounding scenery. Prospective camp owners should tour the lake slowly by water. Note the architectural features of the "Adirondack style" and, just as important, the placement of structures within the landscape. During your trip, consider how the following guidelines enable both old and new structures to blend in: 1.