The Therapeutic Relationship

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Curriculum Vitae

CURRICULUM VITAE David Oakes Wallin Department of Environmental Sciences Huxley College of the Environment Western Washington University Bellingham, Washington 98225-9181 Telephone 360-650-7526; FAX 360-650-7284 E-mail: [email protected]; Web Page: http://faculty.wwu.edu/~wallin Education: Ph.D., Environmental Sciences, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA, August 1990; Dissertation title: Habitat dynamics for an African weaver-bird: the red-billed quelea (Quelea quelea); advisor: Herman H. Shugart M.A., Biology, The College of William and Mary, Williamsburg, VA, January 1982; Thesis title: The influence of environmental conditions on the breeding biology of the bald eagle in Virginia; advisor: Mitchell A. Byrd B.S., Biology, Juniata College, Huntingdon, PA, May 1978 Professional Experience: Current: Professor and Chair, Department of Environmental Sciences, Huxley College of the Environment, Western Washington University (see below for employment history) Research focus: landscape ecology and remote sensing, land-use effects on ecosystem structure and function, landscape genetics, regional analysis of biodiversity patterns, life history attributes and habitat heterogeneity in space and time as determinants of species distribution and abundance patterns, analysis of landscape pattern and pattern change under shifting management objectives, effect of land-use on carbon storage in forest ecosystems. Research Activities and Tools: remote sensing; image analysis and GIS, univariate and multivariate statistics, spatial analysis, -

Ensamhetsmotivet Hos Ivar Arosenius

LINKÖPINGS UNIVERSITET Institutionen för kultur och kommunikation (IKK) Konstvetenskap och visuell kommunikation C-uppsats Ensamhetsmotivet hos Ivar Arosenius Ivar Arosenius’ motifs of solitude Ht 2010 Författare: Niclas Franzén Handledare: Anna Ingemark Milos Innehållsförteckning Inledning .................................................................................................................................................. 2 Syfte .................................................................................................................................................... 2 Material och avgränsningar ................................................................................................................. 2 Teori och metod................................................................................................................................... 3 Tidigare forskning ............................................................................................................................... 5 Bakgrund ................................................................................................................................................. 8 Uppväxt och utbildning ....................................................................................................................... 8 Bohemliv i Göteborg och Värmland ................................................................................................. 11 Paristiden .......................................................................................................................................... -

Preliminary Book Information

Learning Landscape Ecology: Concepts and Techniques for a Sustainable World (2nd Edition) Editors: Sarah E. Gergel, University of British Columbia Monica G. Turner, University of Wisconsin Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Rationale Landscape ecology continues to grow as an exciting discipline with much to offer pressing and emerging problems in environmental science. Much of the strength of the discipline is in its ability to address challenges over large areas, over the scales at which decision-making often occurs. As the world has begun to address more issues related to sustainability and global change, the need for this broad perspective has only increased. Furthermore, spatial data and spatial analysis (the focus of the discipline of landscape ecology), are at the core of analyzing the land cover changes seen world-wide. While spatial dynamics have long been fundamental to conducting terrestrial conservation activities, land management, and reserve design, mapping and spatial themes are also becoming increasingly recognized as fundamental to ecosystem management in aquatic, coastal and marine systems. For these reasons, there is great demand for training in spatial analysis tool accessible to a wide audience. The earlier edition of this book: Learning Landscape Ecology: A Practical Guide to Concepts &Techniques, edited by Gergel and Turner, was the first “hands-on” teaching guide for landscape ecology. The first book of its kind, it provided experience with a diversity of tools and software in the field. The text has sold over 5,000 copies world-wide, used at more than 55 universities, and a 2nd printing was published in 2006. -

Group Therapy Through the Lens of Attachment Theory: Yearly Rhythm

The Fall 2012 From the President Group Kathleen Ulman, PhD, CGP, FAGPA s the leaves start to Afall and the days grow shorter, I remember my excite- Circle ment and anticipation The Newsletter of the of new challenges American Group Psychotherapy Association with the onset of and the International Board for Certification of the new school year that marked the Group Psychotherapists beginning of the rhythm of the coming academic year. AGPA also has its own Group Therapy Through the Lens of Attachment Theory: yearly rhythm. For me, the fall brings thoughts of scheduling Board meetings, An Interview with David Wallin, PhD encouraging scholarship applications, Paul Kaye, PhD, CGP, FAGPA, Co-Chair, Annual Meeting Committee beginning preparations for the Annual Meeting, anticipation of Distance David Wallin, PhD, is a clinical experience; we’re just defined by it. Learning participation, and the start of psychologist in private practice in In contrast, I’ve referred to mentalizing and mindful- many goings-on outside of the aware- Albany and Mill Valley, California. ness as “the double helix of psychological liberation.” ness of many AGPA members. I would Dr. Wallin has been practicing, Why? Because each of these stances fosters the dis-embed- like to take this opportunity to share with you the activities that have been teaching, and writing about psy- ding that loosens the grip of automatic response patterns. taking place on behalf of AGPA over the chotherapy for nearly three decades. Each stance is also affect-regulating, contributes to insight summer while most of us have been on His most recent book, Attachment and empathy, and helps promote the integration of dissoci- vacation, as well as more recently. -

External Mindfulness, Secure (Non)-Attachment, and Healing Relational Trauma: Emerging Models of Wellness for Modern Buddhists and Buddhist Modernism

Journal of Global Buddhism Vol. 17 (2016): 1-21 Research Article External Mindfulness, Secure (Non)-Attachment, and Healing Relational Trauma: Emerging Models of Wellness for Modern Buddhists and Buddhist Modernism Ann Gleig, University of Central Florida Much scholarly attention has been devoted to examining the incorporation of Buddhist-derived meditations such as Mindfulness Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) into psychotherapeutic and medical settings. This paper approaches the cross-fertilization of Buddhist and therapeutic notions of wellness from the opposite direction by exploring Dharma Punx teacher Josh Korda’s interweaving of psychoanalytic developmental theory and affective neuroscience into his Buddhist teachings. Korda provides a useful case study of some of the main patterns emerging from psychotherapeutically informed American Buddhist convert lineages. One of these, I argue, is a “relational turn,” a more context-sensitive approach to individual meditation practice and an increasing interest in developing interpersonal and communal dimensions of Buddhist practice. In conclusion, I consider what Korda’s approach and this relational turn suggests in terms of the unfolding of Buddhist modernism in the West. Keywords: Buddhism; Buddhism in America; Buddhism and Psychoanalysis shaved-headed man covered in bright tattoos and dressed casually in a green t-shirt and black sweat pants sat comfortably, one leg over another, in a chair at the front of the room. As he smiled at the sixty or so retreatants before him, a Asimilar glimmer to the chunky silver jewelry on his fingers and wrists came off his front teeth. With the ease that his informal attire suggested, Josh Korda shared that he was feeling excited and nervous. -

History of the Arts in the Olympic Games

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the q u alityo f the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. A Bell & Howell Information Company 300 North Zeeb Road. Ann Arbor. Ml 48106-1346 USA 313/761-4700 800/521-0600 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Reproduced with permission ofof the the copyrightcopyright owner.owner. FurtherFurther reproduction reproduction prohibited prohibited without without permission. -

United States Department of State Telephone Directory

United States Department of State Telephone Directory This customized report includes the following section(s): Key Officers List (UNCLASSIFIED) 7/5/2019 Provided by Global Information Services, A/GIS Cover UNCLASSIFIED Key Officers of Foreign Service Posts Afghanistan HRO Jason Beck ICITAP Steve Bennett MGT Lori Johnson KABUL (E) Great Massoud Road, (VoIP, US-based) 301-490-1042, Fax No working Fax, INMARSAT Tel 011-873-761-837-725, OPDAT Jon Smibert Workweek: Saturday - Thursday 0800-1630, Website: POL/MIL Tim Enright https://af.usembassy.gov/ SDO/DATT CDR James Hilton CON Acting DCM Daniel Koski Officer Name PAO Brian Beckmann DCM OMS Abena Owusu-Afriyie GSO Sally Lewis ACS Erin Williams RSO Janet Meyer ALT DIR Michael McCord AID Mikaela Meredith AMB OMS Emily Weston CLO Rachel Cormier CM James DeHart ECON Jeffrey Bowan CM OMS Melisa Woolfolk EEO Daniel Koski Co-CLO Stephanie Sever FMO Jason Beck ECON DEP Brett Makens IMO Stephen Craven FM Gary Hein IPO Roy Timberman HRO Jami Papa ISO Justan Neels INL Marc Shaw ISSO Roy Timberman MGT Lawrence Richter POL Carson Relitz Rocker MLO/ODC COL Brady Wilkins PAO/ADV William Bellis POL DEP Gerard (Jerry) Hodel Algeria POL/MIL Raymond Hotz POSHO Scott Klimper ALGIERS (E) 5, Chemin Cheikh Bachir Ibrahimi, +213 (770) 08- SDO/DATT MAJ Marisa Morand 2000, Fax +213 (23) 47-1781, Workweek: Sun - Thurs 08:00-17:00, SRSO Thomas Barnard Website: https://dz.usembassy.gov/ TREAS Alex Zerden Officer Name US EXEC DIR David Smale AMB OMS Rebecca A. Robinson AMB John R. Bass FM John T. -

Green Fire a History of Huxley College

Green Fire A History of Huxley College 1 1970 World population is 3.7 billion. Troy Abel James Albers Andrew Bach Gigi Berardi Richard Berg Brian Bingham Leo Bodensteiner Environmental Timeline Andrew Bodman David Brakke Scott Brennan Huxley College admitted its first Patrick Buckley Andrew Bunn students in September of 1970. Rebecca Bunn Rabel Burdge A brief environmental chronology Devon Cancilla of the following four decades runs Sea Bong Chang TABLE OF CONTENTS David Clarke along the top of our story. Susan Cook William Dietrich Barbara Donovan 5 Introduction Arlene Doyle Crystal Driver Claire Dyckman Jack Everitt 9 1962—1970 Michael Frome The Experiment Richard Frye Ernst Gayden John Hardy Ruth Harper-Arabie 37 Who Was Thomas Henry Huxley? James Helfield Peter Homman Ronald Kendall Thomas Jr. Lacher Wayne Landis 41 The Concrete Cocoon Jason Levy Brooke Love Robin Matthews Richard Mayer 63 Innovative And Stormy 1970—1974 Timothy McDaniels John McLaughlin Michael Medler Jean Melious John Miles 89 The Huxley Student Experience Scott Miles Huxley College Faculty Gene Miller Debnath Mookherjee Of the approximately 4,000 Huxley College Eugene Myers 105 1974—1978 James Newman Huxley Against The World alumni, forty were chosen to profile in this Gilbert Peterson Lynn Robbins book. Those who were selected illustrate the David Rossiter John Rybczk 121 The Hunt For Balance 1978—1994 incredible range of expertise and leadership Jennifer Seltz David Shull that graduates of the college have achieved. Donald Singh-Cundy To the right is a list of college faculty who Bradley Smith Gary Smith 153 All Grown Up 1994—Present spanned the four decades of its history. -

Cosida Academic All-District™ Men's At-Large Team Released

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: May 11, 2017 CoSIDA Academic All-District™ Men’s At-Large Team Released The 2016-17 College Sports Information Directors of America (CoSIDA) Academic All-District™ Men’s At-Large Team has been released to recognize the nation’s top student-athletes for their combined performances athletically and in the classroom. The Academic All-District™ teams include the student-athletes listed on the following pages and are divided into eight geographic districts across the United States and Canada. This is the sixth year of the expanded Academic All-America® program as CoSIDA moved from recognizing a University Division (Division I) and a College Division (all non-Division I) and has doubled the number of scholar-athletes honored. The expanded teams include NCAA Division I, NCAA Division II and NCAA Division III participants, while the College Division Academic All-America® Team combines NAIA, Canadian and two-year schools. The Division II and III Academic All-America® program is being financially supported by the NCAA Division II and III national governance structures, to assist CoSIDA with handling the awards fulfillment aspects for the 2016-17 DII and DIII Academic All-America® teams program. First-team Academic All-District™ honorees advance to the CoSIDA Academic All-America® Team ballot, where first-, second- and third- team All-America® honorees will be selected later this month. For more information about the Academic All-District™ and Academic All-America® Teams program, please visit www.cosida.com. # # # 2017 Academic All-District™ Men’s At-Large Team District 1 NCAA DIVISION I (CT, MA, ME, NH, NY, RI, VT) FIRST TEAM Sport Name School Yr. -

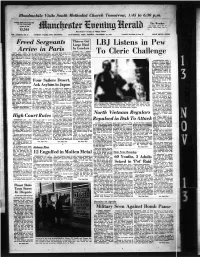

LBJ Listens Pew to Cleric Challenge

Bloodmobile Visits South Methodist Church Tomorrow, 1:45 to 6:30 p,m, ‘ ^ 11 • I _____________________________________________________ - . - ( * 5i amgglM IyNgtPNss < « ■ For The W edi Ended The Weather Fair tonight. Low In 80a. To 1 October ts, 1M7 1 morrow partly aunny. Low hi Sumitig 40a. j 15,544 Mancheater— A CUy^of Village Charm VOL. LXXXVn, NO. 37 (TWENTY PAGES—TWO SECTIONS) MANCHESTER, CONN., MONDAY, NOVEMBER 13, 1967 (Cbuwlfled AdvertUhif on P^ce 17) PRICE SEVEN CENTS Thieves Get Freed Sers^eants Large H aul LBJ Listens Pew Arrive in Paris In L o n d o n LONDON (AP) — Raiders PARIS (AP) —Three U.S. war American Peace Commit "I'm Just going along to look broke into the London headquar To Cleric Challenge ’ Anny aergeanta, freed by the tee, told a reporter on the flight after these boys and take care ters of a giant chain store coop Viet Oongt landed in Parle today from Rome that he had been in of them,” he sedd. erative over the weekend and on the way to report to the De- Hanoi in the past "but that had He conferred with them dur ransacked 600 safety deposit _ fenae Department in Washing nothing to do with this.” ' ing the flight and quoted them boxes in an underground strong ton. All five members of the group as saying they wanted to make room, police said today. > naveU ng under the care of a traveled in the economy class no statements or be photo- First reports estimated the WASHINGTON (AP) — State Department officer from compartment of the Pan Ameri- graphed before they had a haul at g2.8 million but a store President Johnson spent a the U.S. -

Psychologist Psychoanalytic Practitioners National Coalition of Mental Health Professionals and William Fried

VOLUME XXVIII, NO. 2 SPRING 2008 TABLE OF CONTENTs FROM THE PRESIDENT JUSTIN CLEMONS AND RUSSELL GRIGG’S JACQUES LACAN PSYCHOANALYTIC SELF-INTEREST AND PSYCHOANALYTIC VISION AND THE OTHER SIDE OF PSYCHOANALYSIS: NANCY MCWILLIAMS ................................................. 1 REFLECTIONS ON SEMINAR XVII PSYCHOANALYTIC ABSTRACTS NOW AN ONLINE PUBLICATION GREG NOVIE............................................................43 ALVIN WALKER………..…......................................5 COMMENT ON DREW WESTEN’S THE POLITICAL BRAIN PSYCHOANALYTIC RESEARCH HAROLD DAVIS.........................................................45 BRIDGING THE GAP BETWEEN PSYCHOANALYTIC RESEARCH AND COMMITTEE REPORTS PRACTICE APA SUMMIT ON VIOLENCE AND ABUSE IN RELATIONSHIPS PATRICK LUYTENS, SIDNEY BLATT, AND JOZEF MARILYN JACOBS........................................................49 CORVELEYN..............................................................6 NEW DIVISION MEMBERS: ARTICLES JANUARY 2007 TO MARCH 2008..................................53 PSYCHOANALYTIC ETHNOGRAPHY AND FILMMAKING SEXUALITIES AND GENDER IDENTITY RICARDO AINSLIE.......................................................12 SCOTT PYTLUK AND KENNETH MAGUIRE.............................57 POST MODERN METAPHOR:S CONTINUING EDUCATION HENRY SEIDEN..................................................................14 LAURA PORTER..........................................................58 LOVE ME; LOVE MY GECKO FROM THE EDITOR KAREN ZELAN............................................................16 -

Promoting Secure Attachments Through Group Therapy

Promoting Secure Attachments through Group Therapy Special Institute Monday, February 23 2015 Hyatt Regency San Francisco Two-Day Institute at Embarcadero Center Tuesday & Wednesday, February 24-25 Three-Day Conference Thursday, Friday, Saturday, February 26-28 he Annual Institute and Conference elcome to the streets of San Francisco — no, not the 70’s Tprovides participants from diverse clinical television show, but to our wonderful 72nd Annual Meeting here disciplines the opportunity to advance their W knowledge, skills and training in group in one of the most vibrant, cosmopolitan cities in the country. We psychotherapy and related fields. The Annual haven’t been here since 2006 and I hope you are as eager as I am to Meeting experience promises to include the experience all that this city has to offer — Fisherman’s Wharf, the development of new clinical approaches, refinement of therapeutic methods, exchange Mission district, Golden Gate park, the Ferry Building right outside the of clinical and empirical knowledge with back door of the Hyatt Regency, and great restaurants, to name just a colleagues, exposure to current research and few of the delights of San Francisco. theory, and the opportunity to participate in a I can also tell you that our Institute and Conference promises to be as exciting, multidisciplinary peer support network. The Annual Meeting consists of Special enriching and enlivening as the city which is hosting it. As you’ll see in our program, we Institute presentations, the two-day Institute have a full array of both state-of-the-art and tried-and-true offerings by the most gifted devoted to small group teaching primarily in group therapists around.