Indigenous History of the Pilbara

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Introduction of an Alien Fish Species in the Pilbara Region of Western

RECORDS OF THE WESTERN AUSTRALIAN MUSEUM 33 108–114 (2018) DOI: 10.18195/issn.0312-3162.33(1).2018.108-114 Introduction of an alien fsh species in the Pilbara region of Western Australia Dean C. Thorburn1, James J. Keleher1 and Simon G. Longbottom1 1 Indo-Pacifc Environmental, PO Box 191, Duncraig East, Western Australia 6023, Australia. * Corresponding author: [email protected] ABSTRACT – Until recently rivers of the Pilbara region of north Western Australia were considered to be free of introduced fsh species. However, a survey of aquatic fauna of the Fortescue River conducted in March 2017 resulted in the capture of 19 Poecilia latipinna (Sailfn Molly) throughout a 25 km section of the upper catchment. This represented the frst record of an alien fsh species in the Pilbara region and the most northern record in Western Australia. Based on the size of the individuals captured, the distribution over which they were recorded and the fact that the largest female was mature, P. latipinna appeared to be breeding. While P. latipinna was unlikely to physically threaten native fsh species in the upper reaches of the Fortescue River, potential spatial and dietary competition may exist if it reaches downstream waters where native fsh diversity is higher and dietary overlap is likely. As P. latipinna has the potential to affect macroinvertebrate communities, some risk may also exist to the macroinvertebrate community of the Fortescue Marsh, which is located immediately downstream, and which is valued for its numerous short range endemic aquatic invertebrates. The current fnding indicated that despite the relative isolation of the river and presence of a low human population, this remoteness does not mean the river is safe from the potential impact of species introductions. -

1 Early Earth June06.Indd

The Early Earth & First Signs of Life Earth began to solidify and divide into its layers (Core, Mantle and Crust) more than 4 billion years ago – and finally to have a solid surface – unlike Jupiter and Saturn, but more like Mars. But it was not until about 3.8 billion years ago that life is first recorded on Earth by structures called stromatolites “constructed” by bacteria. Their distant relatives are still alive in Australia today, building the same monuments. The early Earth lacked much of an atmosphere and so was heavily pummeled by meteorites. It was a bleak and hellish place, with volcanoes blasting lava fountains in the air, fumeroles steaming – and little water around. But it was this very volcanic activity that formed water and produced the gases which made up an atmosphere, when temperatures on the Earth’s surface finally dipped below 100 o C. – an atmosphere dominated by carbon dioxide, some nitrogen, water vapour, methane and smaller amounts of hydrogen sulfide (which is what makes rotten eggs smell so bad!), hydrogen cyanide and ammonia. There was no significant amount of oxygen in this early atmosphere. By 3800 million years ago there was a solid surface on Earth, and sediments were actually forming – meaning that wind and running water had to be present. How do we know this? Geologists who have studied modern rivers and desert sands, ocean shores and ocean depths compare the sands and muds today with the same sorts of structures (such as ripple marks) and textures preserved in the ancient rocks of the Macdonnell Ranges of Central Australia and the Pilbara region of Western Australia and see many similarities. -

The Nature of Northern Australia

THE NATURE OF NORTHERN AUSTRALIA Natural values, ecological processes and future prospects 1 (Inside cover) Lotus Flowers, Blue Lagoon, Lakefield National Park, Cape York Peninsula. Photo by Kerry Trapnell 2 Northern Quoll. Photo by Lochman Transparencies 3 Sammy Walker, elder of Tirralintji, Kimberley. Photo by Sarah Legge 2 3 4 Recreational fisherman with 4 barramundi, Gulf Country. Photo by Larissa Cordner 5 Tourists in Zebidee Springs, Kimberley. Photo by Barry Traill 5 6 Dr Tommy George, Laura, 6 7 Cape York Peninsula. Photo by Kerry Trapnell 7 Cattle mustering, Mornington Station, Kimberley. Photo by Alex Dudley ii THE NATURE OF NORTHERN AUSTRALIA Natural values, ecological processes and future prospects AUTHORS John Woinarski, Brendan Mackey, Henry Nix & Barry Traill PROJECT COORDINATED BY Larelle McMillan & Barry Traill iii Published by ANU E Press Design by Oblong + Sons Pty Ltd The Australian National University 07 3254 2586 Canberra ACT 0200, Australia www.oblong.net.au Email: [email protected] Web: http://epress.anu.edu.au Printed by Printpoint using an environmentally Online version available at: http://epress. friendly waterless printing process, anu.edu.au/nature_na_citation.html eliminating greenhouse gas emissions and saving precious water supplies. National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry This book has been printed on ecoStar 300gsm and 9Lives 80 Silk 115gsm The nature of Northern Australia: paper using soy-based inks. it’s natural values, ecological processes and future prospects. EcoStar is an environmentally responsible 100% recycled paper made from 100% ISBN 9781921313301 (pbk.) post-consumer waste that is FSC (Forest ISBN 9781921313318 (online) Stewardship Council) CoC (Chain of Custody) certified and bleached chlorine free (PCF). -

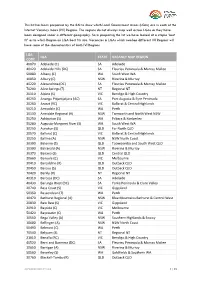

Lgas) Are in Each of the Internet Vacancy Index (IVI) Regions

This list has been prepared by the RAI to show which Local Government Areas (LGAs) are in each of the Internet Vacancy Index (IVI) Regions. The regions do not always map well across LGAs as they have been designed under a different geography. So in preparing the list we have looked at a simple ‘best fit’ as to which Region an LGA best fits into. Vacancies in LGAs which overlap different IVI Regions will have some of the characteristics of both IVI Regions. LGA LGA STATE VACANCY MAP REGION CODE 40070 Adelaide (C) SA Adelaide 40120 Adelaide Hills (DC) SA Fleurieu Peninsula & Murray Mallee 50080 Albany (C) WA South West WA 10050 Albury (C) NSW Riverina & Murray 40220 Alexandrina (DC) SA Fleurieu Peninsula & Murray Mallee 70200 Alice Springs (T) NT Regional NT 20110 Alpine (S) VIC Bendigo & High Country 40250 Anangu Pitjantjatjara (AC) SA Port Augusta & Eyre Peninsula 20260 Ararat (RC) VIC Ballarat & Central Highlands 50210 Armadale (C) WA Perth 10130 Armidale Regional (A) NSW Tamworth and North West NSW 50250 Ashburton (S) WA Pilbara & Kimberley 50280 Augusta-Margaret River (S) WA South West WA 30250 Aurukun (S) QLD Far North QLD 20570 Ballarat (C) VIC Ballarat & Central Highlands 10250 Ballina (A) NSW NSW North Coast 30300 Balonne (S) QLD Toowoomba and South West QLD 10300 Balranald (A) NSW Riverina & Murray 30370 Banana (S) QLD Central QLD 20660 Banyule (C) VIC Melbourne 30410 Barcaldine (R) QLD Outback QLD 30450 Barcoo (S) QLD Outback QLD 70420 Barkly (R) NT Regional NT 40310 Barossa (DC) SA Adelaide 40430 Barunga West (DC) SA Yorke Peninsula -

Regions and Local Government Areas Western Australia

IRWIN THREE 115°E 120°E 125°E SPRINGS PERENJORI YALGOO CARNAMAH MENZIES COOROW Kimberley DALWALLINU MOUNT MARSHALL REGIONS AND LOCAL Pilbara MOORA DANDARAGAN Gascoyne KOORDA MUKINBUDIN GOVERNMENT AREAS WONGAN-BALLIDU Midwest DOWERIN WESTONIA YILGARN Goldfields-Esperance VICTORIA PLAINS TRAYNING GOOMALLING NUNGARIN WESTERN AUSTRALIA - 2011 Wheatbelt GINGIN Perth WYALKATCHEM Peel CHITTERING South West Great KELLERBERRIN Southern TOODYAY CUNDERDIN MERREDIN NORTHAM TAMMIN YORK TIMOR QUAIRADING BRUCE ROCK NAREMBEEN 0 50 100 200 300 400 SEA BEVERLEY SERPENTINE- Kilometres BROOKTON JARRAHDALE CORRIGIN KONDININ 15°S MANDURAH WANDERING PINGELLY 15°S MURRAY CUBALLING KULIN WICKEPIN WAROONA BODDINGTON Wyndham NARROGIN WYNDHAM-EAST KIMBERLEY LAKE GRACE HARVEY WILLIAMS DUMBLEYUNG KUNUNURRA COLLIE WAGIN BUNBURY DARDANUP WEST ARTHUR CAPEL RAVENSTHORPE WOODANILLING KENT DONNYBROOK- KATANNING BUSSELTON BALINGUP BOYUP BROOK BROOMEHILL- AUGUSTA- KOJONUP JERRAMUNGUP MARGARET BRIDGETOWN- TAMBELLUP RIVER GREENBUSHES GNOWANGERUP NANNUP CRANBROOK Derby MANJIMUP DERBY-WEST KIMBERLEY PLANTAGENET BROOME KIMBERLEY ALBANY DENMARK Fitzroy Crossing Halls Creek INSET BROOME INDIAN OCEAN HALLS CREEK 20°S 20°S PORT HEDLAND Wickham Y Dampier PORT HEDLAND KARRATHA Roebourne R ROEBOURNE O T I R Onslow EAST PILBARA Pannawonica PILBARA R Exmouth E T ASHBURTON N EXMOUTH Tom Price R E H Paraburdoo Newman T R O N CARNARVON GASCOYNE UPPER GASCOYNE CARNARVON 25°S 25°S MEEKATHARRA NGAANYATJARRAKU WILUNA Denham MID WEST SHARK BAY MURCHISON Meekatharra A I L CUE A R NORTHAMPTON T Kalbarri -

Pilbara Shorebirds and Seabirds

Shorebirds and seabirds OF THE PILBARA COAST AND ISLANDS Montebello Islands Pilbara Region Dampier Barrow Sholl Island Karratha Island PERTH Thevenard Island Serrurier Island South Muiron Island COASTAL HIGHWAY Onslow Pannawonica NORTH WEST Exmouth Cover: Greater sand plover. This page: Great knot. Photos – Grant Griffin/DBCA Photos – Grant page: Great knot. This Greater sand plover. Cover: Shorebirds and seabirds of the Pilbara coast and islands The Pilbara coast and islands, including the Exmouth Gulf, provide important refuge for a number of shorebird and seabird species. For migratory shorebirds, sandy spits, sandbars, rocky shores, sandy beaches, salt marshes, intertidal flats and mangroves are important feeding and resting habitat during spring and summer, when the birds escape the harsh winter of their northern hemisphere breeding grounds. Seabirds, including terns and shearwaters, use the islands for nesting. For resident shorebirds, including oystercatchers and beach stone-curlews, the islands provide all the food, shelter and undisturbed nesting areas they need. What is a shorebird? Shorebirds, also known as ‘waders’, are a diverse group of birds mostly associated with wetland and coastal habitats where they wade in shallow water and feed along the shore. This group includes plovers, sandpipers, stints, curlews, knots, godwits and oystercatchers. Some shorebirds spend their entire lives in Australia (resident), while others travel long distances between their feeding and breeding grounds each year (migratory). TYPES OF SHOREBIRDS Roseate terns. Photo – Grant Griffin/DBCA Photo – Grant Roseate terns. Eastern curlew Whimbrel Godwit Plover Turnstone Sandpiper Sanderling Diagram – adapted with permission from Ted A Morris Jr. Above: LONG-DISTANCE TRAVELLERS To never experience the cold of winter sounds like a good life, however migratory shorebirds put a lot of effort in achieving their endless summer. -

The Riparian Flora and Plant Communities of the Pilbara Region Of

DOI: 10.18195/issn.0313-122x.78(2).2015.485-513 Records of the Western Australian Museum, Supplement 78: 485–513 (2015). The riparian fl ora and plant communities of the Pilbara region of Western Australia M.N. Lyons Department of Parks and Wildlife, Science and Conservation Division, Kieran McNamara Conservation Science Centre, Locked Bag 104, Bentley Delivery Centre, Western Australia 6983, Australia. Email: [email protected] Abstract – A survey of riparian fl ora and plant communities was undertaken at 98 wetlands and rivers in the Pilbara region of Western Australia. Sampling was quadrat-based, with fl oristics, surface soils and wetland attributes recorded. Selected sites captured the full range of Pilbara wetland types including springs, river pools, claypans, salt marshes and rock pools. A total of 455 taxa was recorded from the survey sites, representing ca. 25% of the known fl ora of the Pilbara bioregion. The fl ora is dominated by taxa with Eremaean and tropical affi nities, with only six taxa endemic in the region. Of recorded taxa known from four or fewer bioregions, most are shared with the adjacent Carnarvon and Gascoyne bioregions rather than the adjoining internally draining deserts. Sixteen taxa of conservation signifi cance were documented, with claypans, the Fortescue Marsh, and Millstream and Karijini National Park sites dominating occurrences of rare species. Eight major groups were defi ned by classifying wetlands in terms of species presence/absence data. Floristic patterning was strongly aligned with the major wetland types (geomorphic/hydrological) used in the primary sampling stratifi cation. A combination of wetland morphology/hydrological setting, site edaphic attributes and distance to the coast were dominant variables related to riparian fl oristic composition. -

Landcorp Denmark East Development Precinct Flora and Fauna Survey

LandCorp Denmark East Development Precinct Flora and Fauna Survey October 2016 Executive summary Introduction Through the Royalties for Regions “Growing our South” initiative, the Shire of Denmark has received funding to provide a second crossing of the Denmark River, to upgrade approximately 6.5 km of local roads and to support the delivery of an industrial estate adjacent to McIntosh Road. GHD Pty Ltd (GHD) was commissioned by LandCorp to undertake a biological assessment of the project survey area. The purpose of the assessment was to identify and describe flora, vegetation and fauna within the survey area. The outcomes of the assessment will be used in the environmental assessment and approvals process and will identify the possible need for, and scope of, further field investigations will inform environmental impact assessment of the road upgrades. The survey area is approximately 68.5 ha in area and includes a broad area of land between Scotsdale Road and the Denmark River and the road reserve and adjacent land along East River Road and McIntosh Road between the Denmark Mt Barker Road and South Western Highway. A 200 m section north and south along the Denmark Mt Barker Road from East River Road was also surveyed. The biological assessment involved a desktop review and three separate field surveys, including a winter flora and fauna survey, spring flora and fauna survey and spring nocturnal fauna survey. Fauna surveys also included the use of movement sensitive cameras in key locations. Key biological aspects The key biological aspects and constraints identified for the survey area are summarised in the following table. -

Some of Western Australia's Threatened Animal Species

Some of Western Australia’s Threatened Animal Species Banded Hare-wallaby / Munning (Mala) ⧫ Listing: Vulnerable ⧫ Latin Name: Lagostrophus fasciatus fasciatus ⧫ Description: Nocturnal, small marsupial with a short nose and grey fur speckled with yellow and silver. ⧫ Diet: Herbivore; grasses and shrubs. ⧫ Habitat: Under thickets of Acacia on sandplains. Previously found in south-west Australia but now only found on a number of islands in Shark Bay (Bernier, Dorre, & Faure Islands). ⧫ Threats: Introduced species (feral cats, foxes, black rats), fires, & disease. ⧫ Fun fact: There were no banded hare wallabies on Faure Island but a population was successfully introduced in 2004 and are doing well. Image source: http://www.australianwildlife.org/media/59032/banded-hare-wallaby_dsc8806scrn.jpg Bilby ⧫ Listing: Vulnerable ⧫ Latin Name: Macrotis lagotis ⧫ Description: Nocturnal, small marsupial with a long snout, big rabbit-like ears, and a long tail; bilbies tend to be grayish brown in color. ⧫ Diet: Omnivore; insects, seeds, spiders, bulbs, fruit, fungi, and very small animals. ⧫ Habitat: Burrows in diverse habitats from Mitchell grass to stony downs, sandplains, & dunefields; in Northeastern WA and central NT. ⧫ Threats: Changing fire regimes, competition with herbivores for resources, foxes & feral cats. ⧫ Fun fact: They do not drink water at all, getting all their moisture from Diet. Image source: http://www.australianwildlife.org/media/66801/greater-bilby_wlawler_sml.jpg Black-footed Tree-rat (Djintamoonga) ⧫ Listing: Vulnerable ⧫ Latin Name: Mesembriomys gouldii ⧫ Description: A large, nocturnal, arboreal, native rodent, on average between 250-310 mm and 650-880g. They have grey fur with black ears and black tail with a white tip. ⧫ Diet: Mostly herbivore; fruits and seeds with some invertebrates, flowers, and grasses. -

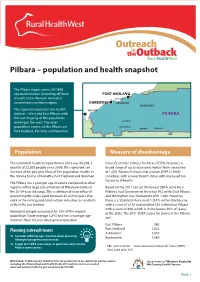

Pilbara – Population and Health Snapshot

Pilbara – population and health snapshot The Pilbara region covers 507,896 square kilometres (including offshore islands) and is Western Australia’s second most northern region. The region incorporates two health districts – West and East Pilbara, with the vast majority of the population residing in the west. The main population centres of the Pilbara are Port Hedland, Karratha and Newman. Population Measure of disadvantage The estimated resident population in 2013 was 66,298, a Socio-Economic Indexes for Areas (SEIFA) measures a growth of 22,209 people since 2006. This represents an broad range of socio-economic indices from a baseline increase of 6% per year. Most of the population resides in of 1,000. Research shows that a lower SEIFA (<1000) the mining towns of Karratha, Port Hedland and Newman. correlates with a lower health status with increased risk factors to ill health. The Pilbara has a younger age structure compared to other regions, with a large concentration of Pilbara residents in Based on the 2011 census the lowest SEIFA score for a the 20-54 year old range. This is attributed to an influx of Pilbara Local Government Area was 962 in the East Pilbara, predominantly males aged between 20 and 44 years that and the highest was Roebourne with 1,060. However, work in the mining and construction industries as residents there is a Statistical Area Level 1 (SA1) within Roebourne or fly-in/fly-out workers. with a score of 1,136 and another SA1 within East Pilbara with a score of 496, which is in the lowest 30% of scores Aboriginal people accounted for 16% of the region’s in the State. -

Jewel Bugs of Australia (Insecta, Heteroptera, Scutelleridae)1

© Biologiezentrum Linz/Austria; download unter www.biologiezentrum.at Jewel Bugs of Australia (Insecta, Heteroptera, Scutelleridae)1 G. CASSIS & L. VANAGS Abstract: The Australian genera of the Scutelleridae are redescribed, with a species exemplar of the ma- le genitalia of each genus illustrated. Scanning electron micrographs are also provided for key non-ge- nitalic characters. The Australian jewel bug fauna comprises 13 genera and 25 species. Heissiphara is described as a new genus, for a single species, H. minuta nov.sp., from Western Australia. Calliscyta is restored as a valid genus, and removed from synonymy with Choerocoris. All the Australian species of Scutelleridae are described, and an identification key is given. Two new species of Choerocoris are des- cribed from eastern Australia: C. grossi nov.sp. and C. lattini nov.sp. Lampromicra aerea (DISTANT) is res- tored as a valid species, and removed from synonymy with L. senator (FABRICIUS). Calliphara nobilis (LIN- NAEUS) is recorded from Australia for the first time. Calliphara billardierii (FABRICIUS) and C. praslinia praslinia BREDDIN are removed from the Australian biota. The identity of Sphaerocoris subnotatus WAL- KER is unknown and is incertae sedis. A description is also given for the Neotropical species, Agonoso- ma trilineatum (FABRICIUS); a biological control agent recently introduced into Australia to control the pasture weed Bellyache Bush (Jatropha gossypifolia, Euphorbiaceae). Coleotichus borealis DISTANT and C. (Epicoleotichus) schultzei TAUEBER are synonymised with C. excellens (WALKER). Callidea erythrina WAL- KER is synonymized with Lampromicra senator. Lectotype designations are given for the following taxa: Coleotichus testaceus WALKER, Coleotichus excellens, Sphaerocoris circuliferus (WALKER), Callidea aureocinc- ta WALKER, Callidea collaris WALKER and Callidea curtula WALKER. -

Human Refugia in Australia During the Last Glacial Maximum and Terminal Pleistocene: a Geospatial Analysis of the 25E12 Ka Australian Archaeological Record

Journal of Archaeological Science 40 (2013) 4612e4625 Contents lists available at SciVerse ScienceDirect Journal of Archaeological Science journal homepage: http://www.elsevier.com/locate/jas Human refugia in Australia during the Last Glacial Maximum and Terminal Pleistocene: a geospatial analysis of the 25e12 ka Australian archaeological record Alan N. Williams a,*, Sean Ulm b, Andrew R. Cook c, Michelle C. Langley d, Mark Collard e a Fenner School of Environment and Society, The Australian National University, Building 48, Linnaeus Way, Canberra, ACT 0200, Australia b Department of Anthropology, Archaeology and Sociology, School of Arts and Social Sciences, James Cook University, PO Box 6811, Cairns, QLD 4870, Australia c School of Biological, Earth and Environmental Sciences, The University of New South Wales, NSW 2052, Australia d Institute of Archaeology, University of Oxford, Oxford OX1 2PG, United Kingdom e Human Evolutionary Studies Program and Department of Archaeology, Simon Fraser University, Burnaby, British Columbia, Canada article info abstract Article history: A number of models, developed primarily in the 1980s, propose that Aboriginal Australian populations Received 13 February 2013 contracted to refugia e well-watered ranges and major riverine systems e in response to climatic Received in revised form instability, most notably around the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM) (w23e18 ka). We evaluate these 3 June 2013 models using a comprehensive continent-wide dataset of archaeological radiocarbon ages and geospatial Accepted 17 June 2013 techniques. Calibrated median radiocarbon ages are allocated to over-lapping time slices, and then K-means cluster analysis and cluster centroid and point dispersal pattern analysis are used to define Keywords: Minimum Bounding Rectangles (MBR) representing human demographic patterns.