Introduction of an Alien Fish Species in the Pilbara Region of Western

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cape York Peninsula Parks and Reserves Visitor Guide

Parks and reserves Visitor guide Featuring Annan River (Yuku Baja-Muliku) National Park and Resources Reserve Black Mountain National Park Cape Melville National Park Endeavour River National Park Kutini-Payamu (Iron Range) National Park (CYPAL) Heathlands Resources Reserve Jardine River National Park Keatings Lagoon Conservation Park Mount Cook National Park Oyala Thumotang National Park (CYPAL) Rinyirru (Lakefield) National Park (CYPAL) Great state. Great opportunity. Cape York Peninsula parks and reserves Thursday Possession Island National Park Island Pajinka Bamaga Jardine River Resources Reserve Denham Group National Park Jardine River Eliot Creek Jardine River National Park Eliot Falls Heathlands Resources Reserve Captain Billy Landing Raine Island National Park (Scientific) Saunders Islands Legend National Park National park Sir Charles Hardy Group National Park Mapoon Resources reserve Piper Islands National Park (CYPAL) Wen Olive River loc Conservation park k River Wuthara Island National Park (CYPAL) Kutini-Payamu Mitirinchi Island National Park (CYPAL) Water Moreton (Iron Range) Telegraph Station National Park Chilli Beach Waterway Mission River Weipa (CYPAL) Ma’alpiku Island National Park (CYPAL) Napranum Sealed road Lockhart Lockhart River Unsealed road Scale 0 50 100 km Aurukun Archer River Oyala Thumotang Sandbanks National Park Roadhouse National Park (CYPAL) A r ch KULLA (McIlwraith Range) National Park (CYPAL) er River C o e KULLA (McIlwraith Range) Resources Reserve n River Claremont Isles National Park Coen Marpa -

Your Great Barrier Reef

Your Great Barrier Reef A masterpiece should be on display but this one hides its splendour under a tropical sea. Here’s how to really immerse yourself in one of the seven wonders of the world. Yep, you’re going to get wet. southern side; and Little Pumpkin looking over its big brother’s shoulder from the east. The solar panels, wind turbines and rainwater tanks that power and quench this island are hidden from view. And the beach shacks are illusory, for though Pumpkin Island has been used by families and fishermen since 1964, it has been recently reimagined by managers Wayne and Laureth Rumble as a stylish, eco- conscious island escape. The couple has incorporated all the elements of a casual beach holiday – troughs in which to rinse your sandy feet, barbecues on which to grill freshly caught fish and shucking knives for easy dislodgement of oysters from the nearby rocks – without sacrificing any modern comforts. Pumpkin Island’s seven self-catering cottages and bungalows (accommodating up to six people) are distinguished from one another by unique decorative touches: candy-striped deckchairs slung from hooks on a distressed weatherboard wall; linen bedclothes in this cottage, waffle-weave in that; mint-green accents here, blue over there. A pair of legs dangles from one (Clockwise from top left) Book The theme is expanded with – someone has fallen into a deep Pebble Point cottage for the unobtrusively elegant touches, afternoon sleep. private deck pool; “self-catering” such as the driftwood towel rails The island’s accommodation courtesy of The Waterline and the pottery water filters in is self-catering so we arrive restaurant; accommodations Pumpkin Island In summer the caterpillars Feel like you’re marooned on an just the right shade of blue. -

Surface Water Resources of Cape York Peninsula

CAPE YORK PENINSULA LAND USE STRATEGY LAND USE PROGRAM SURFACE WATER RESOURCES OF CAPE YORK PENINSULA A.M. Horn Queensland Department of Primary Industries 1995 r .am1, a DEPARTMENT OF, PRIMARY 1NDUSTRIES CYPLUS is a joint initiative of the Queensland and Commonwealth Governments CAPE YORK PENINSULA LAND USE STRATEGY (CYPLUS) Land Use Program SURFACE WATER RESOURCES OF CAPE YORK PENINSULA A.M.Horn Queensland Department of Primary Industries CYPLUS is a joint initiative of the Queensland and Commonwealth Governments Recommended citation: Horn. A. M (1995). 'Surface Water Resources of Cape York Peninsula'. (Cape York Peninsula Land Use Strategy, Office of the Co-ordinator General of Queensland, Brisbane, Department of the Environment, Sport and Territories, Canberra and Queensland Department of Primary Industries.) Note: Due to the timing of publication, reports on other CYPLUS projects may not be fully cited in the BIBLIOGRAPHY section. However, they should be able to be located by author, agency or subject. ISBN 0 7242 623 1 8 @ The State of Queensland and Commonwealth of Australia 1995. Copyright protects this publication. Except for purposes permitted by the Copyright Act 1968, - no part may be reproduced by any means without the prior written permission of the Office of the Co-ordinator General of Queensland and the Australian Government Publishing Service. Requests and inquiries concerning reproduction and rights should be addressed to: Office of the Co-ordinator General, Government of Queensland PO Box 185 BRISBANE ALBERT STREET Q 4002 The Manager, Commonwealth Information Services GPO Box 84 CANBERRA ACT 2601 CAPE YORK PENINSULA LAND USE STRATEGY STAGE I PREFACE TO PROJECT REPORTS Cape York Peninsula Land Use Strategy (CYPLUS) is an initiative to provide a basis for public participation in planning for the ecologically sustainable development of Cape York Peninsula. -

A Re-Examination of William Hann´S Northern Expedition of 1872 to Cape York Peninsula, Queensland

CSIRO PUBLISHING Historical Records of Australian Science, 2021, 32, 67–82 https://doi.org/10.1071/HR20014 A re-examination of William Hann’s Northern Expedition of 1872 to Cape York Peninsula, Queensland Peter Illingworth TaylorA and Nicole Huxley ACorresponding author. Email: [email protected] William Hann’s Northern Expedition set off on 26 June 1872 from Mount Surprise, a pastoral station west of Townsville, to determine the mineral and agricultural potential of Cape York Peninsula. The expedition was plagued by disharmony and there was later strong criticism of the leadership and its failure to provide any meaningful analysis of the findings. The authors (a descendent of Norman Taylor, expedition geologist, and a descendent of Jerry, Indigenous guide and translator) use documentary sources and traditional knowledge to establish the role of Jerry in the expedition. They argue that while Hann acknowledged Jerry’s assistance to the expedition, his role has been downplayed by later commentators. Keywords: botany, explorers, geology, indigenous history, palaeontology. Published online 27 November 2020 Introduction research prominence. These reinterpretations of history not only highlight the cultural complexity of exploration, but they also During the nineteenth century, exploration for minerals, grazing demonstrate the extent to which Indigenous contributions were and agricultural lands was widespread in Australia, with expedi- obscured or deliberately removed from exploration accounts.4 tions organised through private, public and/or government spon- William Hann’s Northern Expedition to Cape York Peninsula sorship. Poor leadership and conflicting aspirations were common, was not unique in experiencing conflict and failing to adequately and the ability of expedition members to cooperate with one another acknowledge the contributions made by party members, notably in the face of hardships such as food and water shortages, illness and Jerry, Aboriginal guide and interpreter. -

1 Early Earth June06.Indd

The Early Earth & First Signs of Life Earth began to solidify and divide into its layers (Core, Mantle and Crust) more than 4 billion years ago – and finally to have a solid surface – unlike Jupiter and Saturn, but more like Mars. But it was not until about 3.8 billion years ago that life is first recorded on Earth by structures called stromatolites “constructed” by bacteria. Their distant relatives are still alive in Australia today, building the same monuments. The early Earth lacked much of an atmosphere and so was heavily pummeled by meteorites. It was a bleak and hellish place, with volcanoes blasting lava fountains in the air, fumeroles steaming – and little water around. But it was this very volcanic activity that formed water and produced the gases which made up an atmosphere, when temperatures on the Earth’s surface finally dipped below 100 o C. – an atmosphere dominated by carbon dioxide, some nitrogen, water vapour, methane and smaller amounts of hydrogen sulfide (which is what makes rotten eggs smell so bad!), hydrogen cyanide and ammonia. There was no significant amount of oxygen in this early atmosphere. By 3800 million years ago there was a solid surface on Earth, and sediments were actually forming – meaning that wind and running water had to be present. How do we know this? Geologists who have studied modern rivers and desert sands, ocean shores and ocean depths compare the sands and muds today with the same sorts of structures (such as ripple marks) and textures preserved in the ancient rocks of the Macdonnell Ranges of Central Australia and the Pilbara region of Western Australia and see many similarities. -

Preparedness for an Emerging Infectious Disease

pathogens Review Rabies in Our Neighbourhood: Preparedness for an Emerging Infectious Disease Michael P. Ward 1,* and Victoria J. Brookes 2,3 1 Sydney School of Veterinary Science, The University of Sydney, Camden, NSW 2570, Australia 2 School of Animal and Veterinary Sciences, Faculty of Science, Charles Sturt University, Wagga Wagga, NSW 2678, Australia; [email protected] 3 Graham Centre for Agricultural Innovation (NSW Department of Primary Industries and Charles Sturt University), Wagga Wagga, NSW 2678, Australia * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +61-293511607 Abstract: Emerging infectious disease (EID) events have the potential to cause devastating impacts on human, animal and environmental health. A range of tools exist which can be applied to address EID event detection, preparedness and response. Here we use a case study of rabies in Southeast Asia and Oceania to illustrate, via nearly a decade of research activities, how such tools can be systematically integrated into a framework for EID preparedness. During the past three decades, canine rabies has spread to previously free areas of Southeast Asia, threatening the rabies-free status of countries such as Timor Leste, Papua New Guinea and Australia. The program of research to address rabies preparedness in the Oceanic region has included scanning and surveillance to define the emerging nature of canine rabies within the Southeast Asia region; field studies to collect information on potential reservoir species, their distribution and behaviour; participatory and sociological studies to identify priorities for disease response; and targeted risk assessment and disease modelling studies. Lessons learnt include the need to develop methods to collect data in remote regions, and the need to Citation: Ward, M.P.; Brookes, V.J. -

Annan and Endeavour River Freshwater and Estuarine Water Quality Report

Annan and Endeavour River Freshwater and Estuarine Water Quality Report An Assessment of Ambient Water Quality and Effects of Land Use 2002 – 2009 CYMAG Environmental Inc. Cooktown, Queensland March 2012 Written by Christina Howley1. Reviewed by Dr. Andrew Brooks2, Jon Olley2, Jason Carroll3 1: Howley Environmental Consulting/ CYMAG Environmental Inc. 2: Griffith University, Australian Rivers Institute, 3: South Cape York Catchments For a copy of this report or more information e-mail: [email protected] CYMAG: Formed in 1992 as the Cooktown Marine Advisory Committee, CYMAG (Cape York Marine Advisory Group) has evolved from that of a purely advisory capacity to a group that concentrates on a diverse range of environmental mapping, monitoring and assessment programmes. Based on local community concerns, CYMAG developed and implemented a community based water quality monitoring project for the Annan and the Endeavour Rivers in 2002. Monthly monitoring of these rivers has created the first extensive database of water quality monitored on a regular basis on Cape York Peninsula. This baseline data has allowed us to observe impacts that have occurred to these rivers from mining and other developments within the catchments. Data from all of our water quality monitoring projects is entered in the QLD DERM database making it available to natural resource managers and other land users. (Ian McCollum, CEO) Acknowledgements From 2002 to 2005 all work was conducted by CYMAG & SCYC volunteers. Logistical support, boats, vehicles, fuel, monitoring design and project management were contributed by local scientists and volunteers. Initial funding for monitoring equipment came from the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority (GBRMPA). -

The Nature of Northern Australia

THE NATURE OF NORTHERN AUSTRALIA Natural values, ecological processes and future prospects 1 (Inside cover) Lotus Flowers, Blue Lagoon, Lakefield National Park, Cape York Peninsula. Photo by Kerry Trapnell 2 Northern Quoll. Photo by Lochman Transparencies 3 Sammy Walker, elder of Tirralintji, Kimberley. Photo by Sarah Legge 2 3 4 Recreational fisherman with 4 barramundi, Gulf Country. Photo by Larissa Cordner 5 Tourists in Zebidee Springs, Kimberley. Photo by Barry Traill 5 6 Dr Tommy George, Laura, 6 7 Cape York Peninsula. Photo by Kerry Trapnell 7 Cattle mustering, Mornington Station, Kimberley. Photo by Alex Dudley ii THE NATURE OF NORTHERN AUSTRALIA Natural values, ecological processes and future prospects AUTHORS John Woinarski, Brendan Mackey, Henry Nix & Barry Traill PROJECT COORDINATED BY Larelle McMillan & Barry Traill iii Published by ANU E Press Design by Oblong + Sons Pty Ltd The Australian National University 07 3254 2586 Canberra ACT 0200, Australia www.oblong.net.au Email: [email protected] Web: http://epress.anu.edu.au Printed by Printpoint using an environmentally Online version available at: http://epress. friendly waterless printing process, anu.edu.au/nature_na_citation.html eliminating greenhouse gas emissions and saving precious water supplies. National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry This book has been printed on ecoStar 300gsm and 9Lives 80 Silk 115gsm The nature of Northern Australia: paper using soy-based inks. it’s natural values, ecological processes and future prospects. EcoStar is an environmentally responsible 100% recycled paper made from 100% ISBN 9781921313301 (pbk.) post-consumer waste that is FSC (Forest ISBN 9781921313318 (online) Stewardship Council) CoC (Chain of Custody) certified and bleached chlorine free (PCF). -

Chapter 5: Indigenous Peoples and Climate Change

Chapter 5 Indigenous peoples and climate change Climate change has been regarded as a diabolical policy problem globally. The potential threat to the very existence of Indigenous peoples is compounded by legal and institutional barriers raise distinct challenges for our cultures, our lands and our resources.1 More seriously, it poses a threat to the health, cultures and livelihoods of Indigenous peoples both here in Australia and around the world. The importance of culture and its relevance to Indigenous people’s relationship to our lands, is not completely understood and acknowledged in Australia. This is evidenced by the fact that governments continue to develop Indigenous land policy in isolation from other social and economic areas of policy. This is apparent in the development of climate change policy which has generally fallen on the shoulders of government departments responsible for climate change and the environment, absent of involvement from those departments responsible for Indigenous affairs or the social indicators such as health and housing. Understanding the significance of the impacts of climate change on Indigenous peoples requires an understanding of the intimate relationships we share with our environments: our lands and waters; our ecosystems; our natural resources; and all living things is required. Galarrwuy Yunipingu expresses this relationship: I think of land as the history of my nation. It tells me how we came into being and what system we must live. My great ancestors, who live in the times of history, planned everything that we practice now. The law of history says that we must not take land, fight over land, steal land, give land and so on. -

NASA Satellite Sees Blake's Remnants Bringing Desert Rain to Western Australia 10 January 2020, by Rob Gutro

NASA satellite sees Blake's remnants bringing desert rain to Western Australia 10 January 2020, by Rob Gutro southeastern corner of the region. The Australian Government Bureau of Meteorology (ABM) in Western Australia issued several flood warnings at 10:47 a.m. WST on Friday Jan. 10. Flood Warnings were in effect for four areas. There is a Major Flood Warning for the De Grey River Catchment and a Flood Warning for the Fortescue River, Salt Lakes District Rivers, and southwestern parts the Sandy Desert Catchment. ABM said, "Major flooding is occurring in the Nullagine River in the De Grey river catchment. Most upstream locations have now peaked with minor to moderate flooding expected to continue during Friday before flooding starts to ease On Jan. 10, 2020, the MODIS instrument that flies throughout the area over the weekend. Heavy aboard NASA’s Aqua satellite provided a visible image rainfall from ex-Tropical Cyclone Blake has resulted of Ex-tropical storm Blake covering part of Western in in rapid river level rises, and areas of flooding Australia and still generating enough precipitation to call throughout the De Grey river catchment. Flooding for warnings. Credit: NASA Worldview has adversely impacted road conditions particularly at floodways resulting in multiple road closures." Rainfall totals over 24 hours in the De Grey NASA's Aqua satellite provided a look at the catchment indicated 1.30 inches (33 mm) at remnant clouds and storms associated with Ex- Nullagine. tropical Cyclone Blake as it continues to move through Western Australia and generate rainfall On Jan. 10, areas of flooding were occurring in the over desert areas. -

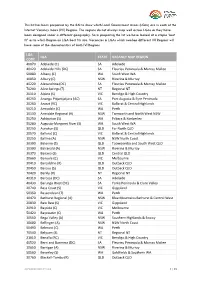

Lgas) Are in Each of the Internet Vacancy Index (IVI) Regions

This list has been prepared by the RAI to show which Local Government Areas (LGAs) are in each of the Internet Vacancy Index (IVI) Regions. The regions do not always map well across LGAs as they have been designed under a different geography. So in preparing the list we have looked at a simple ‘best fit’ as to which Region an LGA best fits into. Vacancies in LGAs which overlap different IVI Regions will have some of the characteristics of both IVI Regions. LGA LGA STATE VACANCY MAP REGION CODE 40070 Adelaide (C) SA Adelaide 40120 Adelaide Hills (DC) SA Fleurieu Peninsula & Murray Mallee 50080 Albany (C) WA South West WA 10050 Albury (C) NSW Riverina & Murray 40220 Alexandrina (DC) SA Fleurieu Peninsula & Murray Mallee 70200 Alice Springs (T) NT Regional NT 20110 Alpine (S) VIC Bendigo & High Country 40250 Anangu Pitjantjatjara (AC) SA Port Augusta & Eyre Peninsula 20260 Ararat (RC) VIC Ballarat & Central Highlands 50210 Armadale (C) WA Perth 10130 Armidale Regional (A) NSW Tamworth and North West NSW 50250 Ashburton (S) WA Pilbara & Kimberley 50280 Augusta-Margaret River (S) WA South West WA 30250 Aurukun (S) QLD Far North QLD 20570 Ballarat (C) VIC Ballarat & Central Highlands 10250 Ballina (A) NSW NSW North Coast 30300 Balonne (S) QLD Toowoomba and South West QLD 10300 Balranald (A) NSW Riverina & Murray 30370 Banana (S) QLD Central QLD 20660 Banyule (C) VIC Melbourne 30410 Barcaldine (R) QLD Outback QLD 30450 Barcoo (S) QLD Outback QLD 70420 Barkly (R) NT Regional NT 40310 Barossa (DC) SA Adelaide 40430 Barunga West (DC) SA Yorke Peninsula -

Regions and Local Government Areas Western Australia

IRWIN THREE 115°E 120°E 125°E SPRINGS PERENJORI YALGOO CARNAMAH MENZIES COOROW Kimberley DALWALLINU MOUNT MARSHALL REGIONS AND LOCAL Pilbara MOORA DANDARAGAN Gascoyne KOORDA MUKINBUDIN GOVERNMENT AREAS WONGAN-BALLIDU Midwest DOWERIN WESTONIA YILGARN Goldfields-Esperance VICTORIA PLAINS TRAYNING GOOMALLING NUNGARIN WESTERN AUSTRALIA - 2011 Wheatbelt GINGIN Perth WYALKATCHEM Peel CHITTERING South West Great KELLERBERRIN Southern TOODYAY CUNDERDIN MERREDIN NORTHAM TAMMIN YORK TIMOR QUAIRADING BRUCE ROCK NAREMBEEN 0 50 100 200 300 400 SEA BEVERLEY SERPENTINE- Kilometres BROOKTON JARRAHDALE CORRIGIN KONDININ 15°S MANDURAH WANDERING PINGELLY 15°S MURRAY CUBALLING KULIN WICKEPIN WAROONA BODDINGTON Wyndham NARROGIN WYNDHAM-EAST KIMBERLEY LAKE GRACE HARVEY WILLIAMS DUMBLEYUNG KUNUNURRA COLLIE WAGIN BUNBURY DARDANUP WEST ARTHUR CAPEL RAVENSTHORPE WOODANILLING KENT DONNYBROOK- KATANNING BUSSELTON BALINGUP BOYUP BROOK BROOMEHILL- AUGUSTA- KOJONUP JERRAMUNGUP MARGARET BRIDGETOWN- TAMBELLUP RIVER GREENBUSHES GNOWANGERUP NANNUP CRANBROOK Derby MANJIMUP DERBY-WEST KIMBERLEY PLANTAGENET BROOME KIMBERLEY ALBANY DENMARK Fitzroy Crossing Halls Creek INSET BROOME INDIAN OCEAN HALLS CREEK 20°S 20°S PORT HEDLAND Wickham Y Dampier PORT HEDLAND KARRATHA Roebourne R ROEBOURNE O T I R Onslow EAST PILBARA Pannawonica PILBARA R Exmouth E T ASHBURTON N EXMOUTH Tom Price R E H Paraburdoo Newman T R O N CARNARVON GASCOYNE UPPER GASCOYNE CARNARVON 25°S 25°S MEEKATHARRA NGAANYATJARRAKU WILUNA Denham MID WEST SHARK BAY MURCHISON Meekatharra A I L CUE A R NORTHAMPTON T Kalbarri