Chapter 5: Indigenous Peoples and Climate Change

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Introduction of an Alien Fish Species in the Pilbara Region of Western

RECORDS OF THE WESTERN AUSTRALIAN MUSEUM 33 108–114 (2018) DOI: 10.18195/issn.0312-3162.33(1).2018.108-114 Introduction of an alien fsh species in the Pilbara region of Western Australia Dean C. Thorburn1, James J. Keleher1 and Simon G. Longbottom1 1 Indo-Pacifc Environmental, PO Box 191, Duncraig East, Western Australia 6023, Australia. * Corresponding author: [email protected] ABSTRACT – Until recently rivers of the Pilbara region of north Western Australia were considered to be free of introduced fsh species. However, a survey of aquatic fauna of the Fortescue River conducted in March 2017 resulted in the capture of 19 Poecilia latipinna (Sailfn Molly) throughout a 25 km section of the upper catchment. This represented the frst record of an alien fsh species in the Pilbara region and the most northern record in Western Australia. Based on the size of the individuals captured, the distribution over which they were recorded and the fact that the largest female was mature, P. latipinna appeared to be breeding. While P. latipinna was unlikely to physically threaten native fsh species in the upper reaches of the Fortescue River, potential spatial and dietary competition may exist if it reaches downstream waters where native fsh diversity is higher and dietary overlap is likely. As P. latipinna has the potential to affect macroinvertebrate communities, some risk may also exist to the macroinvertebrate community of the Fortescue Marsh, which is located immediately downstream, and which is valued for its numerous short range endemic aquatic invertebrates. The current fnding indicated that despite the relative isolation of the river and presence of a low human population, this remoteness does not mean the river is safe from the potential impact of species introductions. -

Cape York Peninsula Parks and Reserves Visitor Guide

Parks and reserves Visitor guide Featuring Annan River (Yuku Baja-Muliku) National Park and Resources Reserve Black Mountain National Park Cape Melville National Park Endeavour River National Park Kutini-Payamu (Iron Range) National Park (CYPAL) Heathlands Resources Reserve Jardine River National Park Keatings Lagoon Conservation Park Mount Cook National Park Oyala Thumotang National Park (CYPAL) Rinyirru (Lakefield) National Park (CYPAL) Great state. Great opportunity. Cape York Peninsula parks and reserves Thursday Possession Island National Park Island Pajinka Bamaga Jardine River Resources Reserve Denham Group National Park Jardine River Eliot Creek Jardine River National Park Eliot Falls Heathlands Resources Reserve Captain Billy Landing Raine Island National Park (Scientific) Saunders Islands Legend National Park National park Sir Charles Hardy Group National Park Mapoon Resources reserve Piper Islands National Park (CYPAL) Wen Olive River loc Conservation park k River Wuthara Island National Park (CYPAL) Kutini-Payamu Mitirinchi Island National Park (CYPAL) Water Moreton (Iron Range) Telegraph Station National Park Chilli Beach Waterway Mission River Weipa (CYPAL) Ma’alpiku Island National Park (CYPAL) Napranum Sealed road Lockhart Lockhart River Unsealed road Scale 0 50 100 km Aurukun Archer River Oyala Thumotang Sandbanks National Park Roadhouse National Park (CYPAL) A r ch KULLA (McIlwraith Range) National Park (CYPAL) er River C o e KULLA (McIlwraith Range) Resources Reserve n River Claremont Isles National Park Coen Marpa -

Your Great Barrier Reef

Your Great Barrier Reef A masterpiece should be on display but this one hides its splendour under a tropical sea. Here’s how to really immerse yourself in one of the seven wonders of the world. Yep, you’re going to get wet. southern side; and Little Pumpkin looking over its big brother’s shoulder from the east. The solar panels, wind turbines and rainwater tanks that power and quench this island are hidden from view. And the beach shacks are illusory, for though Pumpkin Island has been used by families and fishermen since 1964, it has been recently reimagined by managers Wayne and Laureth Rumble as a stylish, eco- conscious island escape. The couple has incorporated all the elements of a casual beach holiday – troughs in which to rinse your sandy feet, barbecues on which to grill freshly caught fish and shucking knives for easy dislodgement of oysters from the nearby rocks – without sacrificing any modern comforts. Pumpkin Island’s seven self-catering cottages and bungalows (accommodating up to six people) are distinguished from one another by unique decorative touches: candy-striped deckchairs slung from hooks on a distressed weatherboard wall; linen bedclothes in this cottage, waffle-weave in that; mint-green accents here, blue over there. A pair of legs dangles from one (Clockwise from top left) Book The theme is expanded with – someone has fallen into a deep Pebble Point cottage for the unobtrusively elegant touches, afternoon sleep. private deck pool; “self-catering” such as the driftwood towel rails The island’s accommodation courtesy of The Waterline and the pottery water filters in is self-catering so we arrive restaurant; accommodations Pumpkin Island In summer the caterpillars Feel like you’re marooned on an just the right shade of blue. -

Surface Water Resources of Cape York Peninsula

CAPE YORK PENINSULA LAND USE STRATEGY LAND USE PROGRAM SURFACE WATER RESOURCES OF CAPE YORK PENINSULA A.M. Horn Queensland Department of Primary Industries 1995 r .am1, a DEPARTMENT OF, PRIMARY 1NDUSTRIES CYPLUS is a joint initiative of the Queensland and Commonwealth Governments CAPE YORK PENINSULA LAND USE STRATEGY (CYPLUS) Land Use Program SURFACE WATER RESOURCES OF CAPE YORK PENINSULA A.M.Horn Queensland Department of Primary Industries CYPLUS is a joint initiative of the Queensland and Commonwealth Governments Recommended citation: Horn. A. M (1995). 'Surface Water Resources of Cape York Peninsula'. (Cape York Peninsula Land Use Strategy, Office of the Co-ordinator General of Queensland, Brisbane, Department of the Environment, Sport and Territories, Canberra and Queensland Department of Primary Industries.) Note: Due to the timing of publication, reports on other CYPLUS projects may not be fully cited in the BIBLIOGRAPHY section. However, they should be able to be located by author, agency or subject. ISBN 0 7242 623 1 8 @ The State of Queensland and Commonwealth of Australia 1995. Copyright protects this publication. Except for purposes permitted by the Copyright Act 1968, - no part may be reproduced by any means without the prior written permission of the Office of the Co-ordinator General of Queensland and the Australian Government Publishing Service. Requests and inquiries concerning reproduction and rights should be addressed to: Office of the Co-ordinator General, Government of Queensland PO Box 185 BRISBANE ALBERT STREET Q 4002 The Manager, Commonwealth Information Services GPO Box 84 CANBERRA ACT 2601 CAPE YORK PENINSULA LAND USE STRATEGY STAGE I PREFACE TO PROJECT REPORTS Cape York Peninsula Land Use Strategy (CYPLUS) is an initiative to provide a basis for public participation in planning for the ecologically sustainable development of Cape York Peninsula. -

A Re-Examination of William Hann´S Northern Expedition of 1872 to Cape York Peninsula, Queensland

CSIRO PUBLISHING Historical Records of Australian Science, 2021, 32, 67–82 https://doi.org/10.1071/HR20014 A re-examination of William Hann’s Northern Expedition of 1872 to Cape York Peninsula, Queensland Peter Illingworth TaylorA and Nicole Huxley ACorresponding author. Email: [email protected] William Hann’s Northern Expedition set off on 26 June 1872 from Mount Surprise, a pastoral station west of Townsville, to determine the mineral and agricultural potential of Cape York Peninsula. The expedition was plagued by disharmony and there was later strong criticism of the leadership and its failure to provide any meaningful analysis of the findings. The authors (a descendent of Norman Taylor, expedition geologist, and a descendent of Jerry, Indigenous guide and translator) use documentary sources and traditional knowledge to establish the role of Jerry in the expedition. They argue that while Hann acknowledged Jerry’s assistance to the expedition, his role has been downplayed by later commentators. Keywords: botany, explorers, geology, indigenous history, palaeontology. Published online 27 November 2020 Introduction research prominence. These reinterpretations of history not only highlight the cultural complexity of exploration, but they also During the nineteenth century, exploration for minerals, grazing demonstrate the extent to which Indigenous contributions were and agricultural lands was widespread in Australia, with expedi- obscured or deliberately removed from exploration accounts.4 tions organised through private, public and/or government spon- William Hann’s Northern Expedition to Cape York Peninsula sorship. Poor leadership and conflicting aspirations were common, was not unique in experiencing conflict and failing to adequately and the ability of expedition members to cooperate with one another acknowledge the contributions made by party members, notably in the face of hardships such as food and water shortages, illness and Jerry, Aboriginal guide and interpreter. -

Preparedness for an Emerging Infectious Disease

pathogens Review Rabies in Our Neighbourhood: Preparedness for an Emerging Infectious Disease Michael P. Ward 1,* and Victoria J. Brookes 2,3 1 Sydney School of Veterinary Science, The University of Sydney, Camden, NSW 2570, Australia 2 School of Animal and Veterinary Sciences, Faculty of Science, Charles Sturt University, Wagga Wagga, NSW 2678, Australia; [email protected] 3 Graham Centre for Agricultural Innovation (NSW Department of Primary Industries and Charles Sturt University), Wagga Wagga, NSW 2678, Australia * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +61-293511607 Abstract: Emerging infectious disease (EID) events have the potential to cause devastating impacts on human, animal and environmental health. A range of tools exist which can be applied to address EID event detection, preparedness and response. Here we use a case study of rabies in Southeast Asia and Oceania to illustrate, via nearly a decade of research activities, how such tools can be systematically integrated into a framework for EID preparedness. During the past three decades, canine rabies has spread to previously free areas of Southeast Asia, threatening the rabies-free status of countries such as Timor Leste, Papua New Guinea and Australia. The program of research to address rabies preparedness in the Oceanic region has included scanning and surveillance to define the emerging nature of canine rabies within the Southeast Asia region; field studies to collect information on potential reservoir species, their distribution and behaviour; participatory and sociological studies to identify priorities for disease response; and targeted risk assessment and disease modelling studies. Lessons learnt include the need to develop methods to collect data in remote regions, and the need to Citation: Ward, M.P.; Brookes, V.J. -

Annan and Endeavour River Freshwater and Estuarine Water Quality Report

Annan and Endeavour River Freshwater and Estuarine Water Quality Report An Assessment of Ambient Water Quality and Effects of Land Use 2002 – 2009 CYMAG Environmental Inc. Cooktown, Queensland March 2012 Written by Christina Howley1. Reviewed by Dr. Andrew Brooks2, Jon Olley2, Jason Carroll3 1: Howley Environmental Consulting/ CYMAG Environmental Inc. 2: Griffith University, Australian Rivers Institute, 3: South Cape York Catchments For a copy of this report or more information e-mail: [email protected] CYMAG: Formed in 1992 as the Cooktown Marine Advisory Committee, CYMAG (Cape York Marine Advisory Group) has evolved from that of a purely advisory capacity to a group that concentrates on a diverse range of environmental mapping, monitoring and assessment programmes. Based on local community concerns, CYMAG developed and implemented a community based water quality monitoring project for the Annan and the Endeavour Rivers in 2002. Monthly monitoring of these rivers has created the first extensive database of water quality monitored on a regular basis on Cape York Peninsula. This baseline data has allowed us to observe impacts that have occurred to these rivers from mining and other developments within the catchments. Data from all of our water quality monitoring projects is entered in the QLD DERM database making it available to natural resource managers and other land users. (Ian McCollum, CEO) Acknowledgements From 2002 to 2005 all work was conducted by CYMAG & SCYC volunteers. Logistical support, boats, vehicles, fuel, monitoring design and project management were contributed by local scientists and volunteers. Initial funding for monitoring equipment came from the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority (GBRMPA). -

Cape York Peninsula Regional Economic & Infrastructure

Submission Number: 212 Attachment D CYP Economic & Infrastructure Framework Project - Report Cape York Peninsula Regional Economic & Infrastructure Framework REPORT November 2007 1 CYP Economic & Infrastructure Framework Project - Report TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION..........................................................................................................4 2. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY..............................................................................................5 3. RECOMMENDATIONS ..............................................................................................17 4. SITUATION REVIEW AND ANALYSIS......................................................................21 Changed Environment ...................................................................................................21 Scope of Review ............................................................................................................21 Post CYPLUS ................................................................................................................22 Natural Heritage Conservation and Management..........................................................25 Needs and Approach..................................................................................................25 Indigenous Point of View............................................................................................29 Appropriate Economic Activities.................................................................................30 Contemporary -

The Endeavour River and Cooktown

The Endeavour River and Cooktown by S. E. STEPHENS " The Endeavour River in Cape York Peninsula shares with Somerset and Cardwell and close to the inner steamer passage, Botany Bay in New South Wales the distinction of having had to be an excellent reason for its development as a port on the an extended visit by Captain James Cook in H:>M:.5. "Endea Torres Strait shipping route to England. Furthermore he thought vour" during the year 1770. But whilst the pause of one week the headwaters of the river contained good pastoral country3. in Botany Bay was to permit the naturalists in the ship's company to go ashore each day to examine an~ collect n~tural A few years later a much more urgent reason for a port at history specimens, the stay in the Endeavour RIver occupIe~ .a the Endeavour River developed. In 1872 William Hann carried period of seven weeks of encampment on the shore. The VISIt out an overland exploration journey from Maryvale Station into to the Endeavour River thus marked the establishment of the Cape York Peninsula. During ~is travels he discovere~ and first English "settlement" on what later became Australian soil. named the Palmer River after SIr Arthur Palmer, PremIer of Certainly the settlement had no part in the plans of Captain Queensland. In this river he found traces of gold. James Cook but was forced upon him when his misadventure on the Venture Mulligan with a party of prospectors followed up this coral reef some forty miles to the south east on 11 June 1770 hint and found payable gold oo.c:the Palmer early in 1873. -

AIR SAFARI Cape York Cairns-The Gulf-Torres Strait Island-Cape York-Lizard Island-Cairns 8 Days/7 Nights from $7800Pp

AIR SAFARI Cape York Cairns-The Gulf-Torres Strait Island-Cape York-Lizard Island-Cairns 8 days/7 nights from $7800pp Day 1 Sat 03 Jul 21 ARRIVAL INTO CAIRNS D On arrival into Cairns, you will be transferred to your city hotel. The rooms will be available from 3pm. This evening you will enjoy dinner at the hotel and the oppor- tunity to meet your fellow enthusiasts and your tour guide. Overnight: Double Tree by Hilton Cairns Day 2 Sun 04 Jul 21 CAIRNS — KARUMBA B,D This morning, we board our Cessna and depart towards Karumba, home to prawn, mud crab and barramundi fishing fleets working in the Gulf of Carpenta- ria. It is also known for fabulous sunsets. After arrival you will enjoy a sea adven- ture, travel 45km along the Norman River in a 10m fully shaded vessel. The tour includes live crab pot lifting, live crab handling and tying, croc spotting and bird watching. At the late afternoon you will indulge in local seafood & fresh produce on a Beachfront BBQ whilst you watch the Sunset over the Gulf of Carpentaria. Overnight: End of the Road Motel Day 3 Mon 05 Jul 21 KARUMBA — HORN ISLAND B,L Continue north up the west side of Cape York, past the tip of Australia, to Horn Island in the Torres Strait, where you will be able to enjoy the changing colours of the Torres Strait. This afternoon venture into the ‘Forgotten Island’- Horn Island with an opportunity to sneak back in time to see remnants of bunkers and hidden revetments during a guided tour, led by local historian and author Vanessa See Kee. -

Koala Context

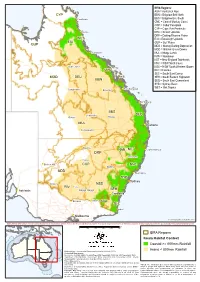

IBRA Regions: AUA = Australian Alps CYP BBN = Brigalow Belt North )" Cooktown BBS = Brigalow Belt South CMC = Central Mackay Coast COP = Cobar Peneplain CYP = Cape York Peninsula ") Cairns DEU = Desert Uplands DRP = Darling Riverine Plains WET EIU = Einasleigh Uplands EIU GUP = Gulf Plains GUP MDD = Murray Darling Depression MGD = Mitchell Grass Downs ") Townsville MUL = Mulga Lands NAN = Nandewar NET = New England Tablelands NNC = NSW North Coast )" Hughenden NSS = NSW South Western Slopes ") CMC RIV = Riverina SEC = South East Corner MGD DEU SEH = South Eastern Highlands BBN SEQ = South East Queensland SYB = Sydney Basin ") WET = Wet Tropics )" Rockhampton Longreach ") Emerald ") Bundaberg BBS )" Charleville )" SEQ )" Quilpie Roma MUL ") Brisbane )" Cunnamulla )" Bourke NAN NET ") Coffs Harbour DRP ") Tamworth )" Cobar ") Broken Hill COP NNC ") Dubbo MDD ") Newcastle SYB ") Sydney ") Mildura NSS RIV )" Hay ") Wagga Wagga SEH Adelaide ") ") Canberra ") ") Echuca Albury AUA SEC )" Eden ") Melbourne © Commonwealth of Australia 2014 INDICATIVE MAP ONLY: For the latest departmental information, please refer to the Protected Matters Search Tool and the Species Profiles & Threats Database at http://www.environment.gov.au/biodiversity/threatened/index.html km 0 100 200 300 400 500 IBRA Regions Koala Habitat Context Coastal >= 800mm Rainfall Produced by: Environmental Resources Information Network (2014) Inland < 800mm Rainfall Contextual data source: Geoscience Australia (2006), Geodata Topo 250K Topographic Data and 10M Topographic Data. Department of Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities (2012). Interim Biogeographic Regionalisation for Australia (IBRA), Version 7. Other data sources: Commonwealth of Australia, Bureau of Meteorology (2003). Mean annual rainfall (30-year period 1961-1990). Caveat: The information presented in this map has been provided by a Department of Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities (2013). -

Slow Breeding Rates and Low Population Connectivity Indicate Australian Palm Cockatoos Are in Severe Decline

Biological Conservation 253 (2021) 108865 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Biological Conservation journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/biocon Policy analysis Slow breeding rates and low population connectivity indicate Australian palm cockatoos are in severe decline Miles V. Keighley a, Stephen Haslett b, Christina N. Zdenek c, Robert Heinsohn a,* a Fenner School of Environment and Society, The Australian National University (ANU), Acton, ACT 2601, Australia b School of Fundamental Science (SFS) & Centre for Public Health Research (CPHR), Massey University, PO Box 11222, Palmerston North, New Zealand c School of Biological Sciences, The University of Queensland, St Lucia, Australia ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: Dispersal dynamics can determine whether animal populations recover or become extinct following decline or Probosciger aterrimus disturbance, especially for species with slow life-histories that cannot replenish quickly. Palm cockatoos (Pro Palm cockatoo bosciger aterrimus) have one of the slowest known reproductive rates of any parrot, and they face steep decline in Endangered species at least one of three populations comprising the meta-population for the species in Australia. Consequently, we Conservation estimated demographic rates and population connectivity using data from published field studies, population Population viability analysis genetics, and vocal dialects. We then used these parameters in a population viability analysis (PVA) to predict the trajectories of the three regional populations, together with the trajectory of the meta-population. We incor porated dispersal between populations using genetic and vocal data modified by landscape permeability, whereby dispersal is limited by a major topographical barrier and non-uniform habitat. Our PVA models suggest that, while dispersal between palm cockatoo populations can reduce local population decline, this is not enough to buffer steep decline in one population with very low breeding success.