The Water Industry As World Heritage

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Thesis, Dissertation

AN EXPLORATION OF SMALL TOWN SENSIBILTIES by Lucas William Winter A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Architecture in Architecture MONTANA STATE UNIVERSITY Bozeman, Montana April 2010 ©COPYRIGHT by Lucas William Winter 2010 All Rights Reserved ii APPROVAL of a thesis submitted by Lucas William Winter This thesis has been read by each member of the thesis committee and has been found to be satisfactory regarding content, English usage, format, citation, bibliographic style, and consistency and is ready for submission to the Division of Graduate Education. Steven Juroszek Approved for the Department of Architecture Faith Rifki Approved for the Division of Graduate Education Dr. Carl A. Fox iii STATEMENT OF PERMISSION TO USE In presenting this thesis in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a master’s degree at Montana State University, I agree that the Library shall make it available to borrowers under rules of the Library. If I have indicated my intention to copyright this thesis by including a copyright notice page, copying is allowable only for scholarly purposes, consistent with “fair use” as prescribed in the U.S. Copyright Law. Requests for permission for extended quotation from or reproduction of this thesis in whole or in parts may be granted only by the copyright holder. Lucas William Winter April 2010 iv TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. THESIS STATEMENT AND INRO…...........................................................................1 2. HISTORY…....................................................................................................................4 3. INTERVIEW - WARREN AND ELIZABETH RONNING….....................................14 4. INTERVIEW - BOB BARTHELMESS.…………………...…....................................20 5. INTERVIEW - RUTH BROWN…………………………...…....................................27 6. INTERVIEW - VIRGINIA COFFEE …………………………...................................31 7. CRITICAL REGIONALISM AS RESPONSE TO GLOBALIZATION…………......38 8. -

Delft University of Technology Upflow Gravel Filtration for Multiple Uses

Delft University of Technology Upflow gravel filtration for multiple uses Sanchez Torres, Luis DOI 10.4233/uuid:61328f49-8ab8-4da1-8e84-4650bddf9a1d Publication date 2016 Document Version Final published version Citation (APA) Sanchez Torres, L. (2016). Upflow gravel filtration for multiple uses. https://doi.org/10.4233/uuid:61328f49- 8ab8-4da1-8e84-4650bddf9a1d Important note To cite this publication, please use the final published version (if applicable). Please check the document version above. Copyright Other than for strictly personal use, it is not permitted to download, forward or distribute the text or part of it, without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), unless the work is under an open content license such as Creative Commons. Takedown policy Please contact us and provide details if you believe this document breaches copyrights. We will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. This work is downloaded from Delft University of Technology. For technical reasons the number of authors shown on this cover page is limited to a maximum of 10. Upflow gravel filtration for multiple uses Upflow gravel filtration for multiple uses Proefschrift Ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor aan de Technische Universiteit Delft, op gezag van de Rector Magnificus Prof. Ir. K. Ch. A. M. Luyben, voorzitter van het College voor Promoties, in het openbaar te verdedigen op 28 april 2016 om 12:30 uur door Luis Dario SÁNCHEZ TORRES Master of Science in Sanitary and Environmental Engineering, Universidad del Valle geboren te Nuquí-Chocó, Colombia This dissertation has been approved by the Promotor: Prof. -

Steven Holl Architects

MUMBAI CITY MUSEUM NORTH WING DESIGN COMPETITION EXHIBITION Shortlisted Teams’ Summaries Steven Holl Architects Winner ADDITION AS SUBTRACTION: Mumbai City Museum’s new North Wing addition is envisioned as a sculpted subtraction from a simple geometry formed by the site boundaries. The sculpted cuts into the white concrete structure bring diffused natural light into the upper galleries. Deeper subtractive cuts bring in exactly twenty-five lumens of natural light to each gallery. The basically orthogonal galleries are given a sense of flow and spatial overlap from the light cuts. The central cut forms a shaded monsoon water basin which runs into a central pool. In addition to evaporative cooling, the pool provides sixty per cent of the museum’s electricity through photovoltaic cells located below the water’s surface. The white concrete structure has an extension of local rough-cut Indian Agra red stone. The circulation through the galleries is one of spatial energy, while the orthogonal layout of the walls foregrounds the spectacular Mumbai City Museum collections. MUMBAI CITY MUSEUM NORTH WING DESIGN COMPETITION EXHIBITION Shortlisted Teams’ Summaries AL_A Honourable mention Using the power of absence to create connections between the old and the new, a sunken courtyard or aangan, taking inspiration from the deep and meaningful significance of the Indian stepwell, is embedded between the existing Museum building and the new North Wing. The courtyard is a metaphor for the cycle of the seasons, capturing the dramatic contrasts of the climate in the fabric of the museum. It is a metaphor for the cycle of time, where people can rethink their place in the world in a space for contemplation and a place for art and culture. -

Lean's Engine Reporter and the Development of The

Trans. Newcomen Soc., 77 (2007), 167–189 View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Research Papers in Economics Lean’s Engine Reporter and the Development of the Cornish Engine: A Reappraisal by Alessandro NUVOLARI and Bart VERSPAGEN THE ORIGINS OF LEAN’S ENGINE REPORTER A Boulton and Watt engine was first installed in Cornwall in 1776 and, from that year, Cornwall progressively became one of the British counties making the most intensive use of steam power.1 In Cornwall, steam engines were mostly employed for draining water from copper and tin mines (smaller engines, called ‘whim engines’ were also employed to draw ore to the surface). In comparison with other counties, Cornwall was characterized by a relative high price for coal which was imported from Wales by sea.2 It is not surprising then that, due to their superior fuel efficiency, Watt engines were immediately regarded as a particularly attractive proposition by Cornish mining entrepreneurs (commonly termed ‘adventurers’ in the local parlance).3 Under a typical agreement between Boulton and Watt and the Cornish mining entre- preneurs, the two partners would provide the drawings and supervise the works of erection of the engine; they would also supply some particularly important components of the engine (such as some of the valves). These expenditures would have been charged to the mine adventurers at cost (i.e. not including any profit for Boulton and Watt). In addition, the mine adventurer had to buy the other components of the engine not directly supplied by the Published by & (c) The Newcomen Society two partners and to build the engine house. -

DSS Senior Serv-Final-Ocr.Pdf

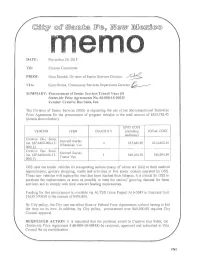

DATE: November 29, 2018 TO: Finance Committee FROM: Gino Rinaldi, Di vision of Senior Services Director ~ VIA: Kyra Ochoa, Community Services Department Director tf::__---- SUI\11\1ARY: Procurement of Senior Services Transit Vans (5) Statewide Price Agreements No. 60-000-15-00015 Vendor: Creative Bus Sales, Inc. The Division of Senior Services (DSS) is requesting the use of the abovementioned Statewide Price Agreement for the procurement of program vehicles in the total amount of $263,758.45 (details shown below). UNIT COST VENDOR ITEM QUANTITY (including TOTAL COST additions) Creative Bus Sales, Starcrafl Starlitc Inc. (SPA#60-000-15- 4 S53,665.89 S214,663.56 Wheelchair \Inn 00015) Creative Bus Sales, Starcraft Starlitc Inc. (SP.'\#60-000-15 - I S49,094.89 S49,094.89 Transit Van 00015) DSS uses the transit \'chicles for transporting seniors (many of whom are frail) to their medical appointments, grocery shopping, meals and activities at five senior centers operated by DSS. These new vehicles will replace the ones that have reached their lifespan. lt is critical for DSS to purchase the replacements as soon as possible to meet the seniors' growing demand for these services, and to comply with their contract fu nding requirements. Funt.ling for this procurement is available via AL TSD Grant Project A 16-5087 in Business Unit 22639.570950 in the amount ofS459.800. By City policy, the City c.:an use either State or Federal Price Agreements without having to bid the item on its own. In addition, by City policy, procurement over $60,000.00 requires City Council approval. -

Biological Aspects of Slow Sand Filtration: Past, Present and Future

Biological Aspects of Slow Sand Filtration: Past, Present and Future SJ. Haig*, G. Collins**, R.L. Davies*** C.C. Dorea**** and C. Quince* *School of Engineering, Rankine Building, University of Glasgow, G12 8LT, UK (E-mail: [email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected]) **School of Natural Sciences, National University of Ireland, Galway, University Road, Galway, Ireland ***School of Infection, and Immunity, Glasgow Biomedical Research Centre, University of Glasgow, G12 8TA, UK (E-mail: [email protected]) ***Département génie civil et génie des eaux/ Civil and Water Engineering, Université Laval, Québec (QC), Canada G1V 0A6 (E-mail: [email protected]) Abstract For over 200 years, slow sand filtration (SSF) has been an effective means of treating water for the control of microbiological contaminants in both small and large community water supplies. However, such systems lost popularity to rapid sand filters mainly due to smaller land requirements and less sensitivity to water quality variations. SSF is still a particularly attractive process because its operation does not require chemicals or electricity. It can achieve a high level of treatment, which is mainly attributed to naturally-occurring, biochemical processes in the filter. Several microbiologically- mediated purification mechanisms (e.g. predation, scavenging, adsorption and bio-oxidation) have been hypothesised or assumed to occur in the biofilm that forms in the filter but these have not yet been comprehensively verified. Thus, SSFs are operated as “black boxes” and knowledge gaps pertaining to the underlying ecology and ecophysiology limit the design and optimisation of the technology. -

Age of Steam" Reconsidered

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Castaldi, Carolina; Nuvolari, Alessandro Working Paper Technological revolution and economic growth: The "age of steam" reconsidered LEM Working Paper Series, No. 2004/11 Provided in Cooperation with: Laboratory of Economics and Management (LEM), Sant'Anna School of Advanced Studies Suggested Citation: Castaldi, Carolina; Nuvolari, Alessandro (2004) : Technological revolution and economic growth: The "age of steam" reconsidered, LEM Working Paper Series, No. 2004/11, Scuola Superiore Sant'Anna, Laboratory of Economics and Management (LEM), Pisa This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/89286 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. www.econstor.eu Laboratory of Economics and Management Sant’Anna School of Advanced Studies Piazza Martiri della Libertà, 33 - 56127 PISA (Italy) Tel. -

Transit Security Procedures Guide

FTA-MA-90-7001-94-2 DOT-VNTSC-FTA-94-8 Pw Transit Security U. S. Department of Transportation Procedures Guide Federal Transit Administration U.S. Department of Transportation Research and Special Programs Administration John A. Volpe National Transportation Systems Center December 1994 Cambridge MA 02142 Final Report NOTICE This document is disseminated under the sponsorship of the Department of Transportation in the interest of information exchange. The United States Government assumes no liability for its contents or use thereof. NOTICE The United States Government does not endorse products or manufacturers. Trade or manufacturers’ names appear herein solely because they are considered essential to the objective of this report. NOTICE This document is disseminated under the sponsorship of the Department of Transportation in the interest of information exchange. The United States Government assumes no liability for its contents or use thereof. NOTICE The United States Government does not endorse products or manufacturers. Trade or manufacturers’ names appear herein solely because they are considered essential to the objective of this report. HETRIC/ENGLISH CONVERSIOY FACTORS ENGLISH TO RETRIC KETRIC TO ENGLISH LENGTH (APPROXIMATE) LENGTH (APPROXIIIATE) 1 inch (in) = 2.5 centimeters (a) 1 milliwter (set) = 0.W inch (in) 1 foot (ft) = 30 centimeters (an) 1 centimeter (cm) = 0.4 inch (in) 1 yard (yd) = 0.9 meter (m) 1 meter Cm) = 3.3 feet (ft) 1 mile (mi) = 1.6 kitaneters (km) 1 swster (m) = 1.1 yards (yd) 1 kilcanster (km) = 0.6 mile -

Spring 2018 Dean's List

Spring 2018 Dean's List Approximately 9,104 Iowa State University students have been recognized for outstanding academic achievement by being named to the Spring Semester 2018 Dean's List. Students named to the Dean's List must have earned a grade point average of at least 3.50 on on a 4.00 scale while carrying a minimum of 12 credit hours of graded course work. NAME CURRICULUM YR CITY STATE COUNTRY Afina Syaurah A Aziz Chemical Engineering 3 Alexandra Lea Aaberg Biology 4 Coralville, IA Pauline E. Aamodt Bioinformatics and Computational Biology 4 Woodbury, MN Aayushi Management Information Systems 4 Charles Alex Abate Management 4 Saint Charles, IL Drew Matthew Abbas Agricultural Studies 4 Alexander, IA Omar M. Abbas Computer Engineering 4 Chicago, IL Brianne Elizabeth Abbasi Animal Science 4 Cedar Rapids, IA Emily Elaine Abbasi Animal Science 4 Cedar Rapids, IA Anthony Michael Abbate Materials Engineering 4 Cary, IL Leah Sophie Abbott Agriculture Specials 5 Paige Jeanette Abbott Veterinary Medicine 4 Elgin, IL Josiah Michael Abbott Industrial Technology 3 West Des Moines, IA Ibrahim Abdalla Marketing 4 West Des Moines, IA Mohamed S. Abdennadher Chemical Engineering 3 Uzma Liyana Abdul Razak Supply Chain Management 4 Kaitlyn Abdulghani Biology 4 Johnston, IA Eric Thomas Abens Industrial Technology 2 Manson, IA Alex‐Marie E. Ablan Graphic Design 4 Eagan, MN Steven Joseph Abramsky Industrial Design 4 Cuba City, WI John Matthew Aceto Landscape Architecture 4 Urbandale, IA Cody Acevedo Animal Ecology 3 Gilbert, IA Melissa Marie Achenbach English 2 Underwood, IA Keely Sarah Acheson Agricultural Business 4 Rushville, IL Ross Allen Ackerman Political Science 3 Harrisburg, SD Aaron Benjamin Ackerman Liberal Arts and Sciences Specials (Non‐Degree) 5 Ames, IA Lexi Ann Ackerman Event Management 4 Rock Rapids, IA Georgia Kate Ackley Food Science (AGLS) 2 Fredericksburg, IA Karly Jo Ackley Kinesiology and Health 2 Manvel, ND Ashley Brianne Acree Sociology 4 Savanna, IL Alexis M. -

13:34:32 Paid Invoice Listing Id: Ap450000.Wow

DATE: 06/05/2017 CITY OF DEKALB PAGE: 1 TIME: 13:34:32 PAID INVOICE LISTING ID: AP450000.WOW FROM 05/01/2017 TO 05/31/2017 VENDOR # INVOICE # INV. DATE CHECK # CHK DATE CHECK AMT INVOICE AMT/ ITEM DESCRIPTION ACCOUNT NUMBER P.O. NUM ITEM AMT ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- ACCTAN ACCURATE TANK TECHNOLOGIES 26595 04/18/17 52109 05/23/17 545.00 545.00 01 FUEL TANK INSPECTIONS 0130332008245 00000000 545.00 VENDOR TOTAL: 545.00 AIRCYC AIR CYCLE CORPORATION 0147608-IN 04/06/17 52110 05/23/17 4,960.00 4,960.00 01 BULB EATER, CHUTE, FILTER 0700003008354 00000000 4,960.00 VENDOR TOTAL: 4,960.00 AIRGAS AIRGAS, INC. 9062965692 04/28/17 52111 05/23/17 650.55 91.05 01 MEDICAL O2 0125272008241 00000000 91.05 9943460718 03/31/17 51954 05/09/17 134.29 134.29 01 CYLINDER RENTAL/REFILL 0130332008226 00000000 67.15 02 CYLINDER RENTAL/REFILL 6000002008226 00000000 67.14 9944247823 04/30/17 52111 05/23/17 650.55 559.50 01 MEDICAL O2 0125272008241 00000000 559.50 VENDOR TOTAL: 784.84 ALECHE ALEXANDER CHEMICAL CORP SLS 10057559 03/29/17 51955 05/09/17 1,224.00 1,224.00 01 CHLORINE/FLUORIDE -POTABLE WTR 6000002008250 00170029 1,224.00 VENDOR TOTAL: 1,224.00 ALEFIR ALEXIS FIRE EQUIPMENT CO 0058740-IN 03/31/17 51956 05/09/17 44.91 44.91 01 STEPWELL LAMP 0125272008226 00000000 44.91 0058909-IN 04/18/17 52112 05/23/17 360.92 227.26 01 SOLENOID VALVE 0125272008226 00000000 227.26 0058922-IN 04/18/17 52112 05/23/17 360.92 133.66 01 DRAIN VALVE 0125272008226 00000000 133.66 VENDOR TOTAL: 405.83 ALUAWA LARSEN CREATIVE INC 1213 03/08/17 51957 05/09/17 72.75 72.75 DATE: 06/05/2017 CITY OF DEKALB PAGE: 2 TIME: 13:34:32 PAID INVOICE LISTING ID: AP450000.WOW FROM 05/01/2017 TO 05/31/2017 VENDOR # INVOICE # INV. -

Case Study – April 2018

Collaborative working to reduce disruption. Case study – April 2018. Collaborative working to reduce disruption. We’re passionate about reducing the impact our work can have on customers across our region. So we’re working with gas, power and telecommunications providers, as well as Transport for London, the London Borough of Croydon and the Greater London Authority, to see how collaborating on planned streetworks can reduce the impact on the lives of all our customers, local communities and the environment, while still improving our services. Background. Over the past year we’ve been working with Atkins and their digital partner Fluxx, challenging ourselves to make improvements in the way we deliver streetworks to reduce their impact on our customers, and become more efficient by collaborating better. We know that our essential streetworks can often Visualising complex data. disrupt our customers’ daily lives, especially when a During our workshops with teams across Thames road reopens only to quickly close again for a different Water, we identified numerous benefits of sharing project, or for another company to start work. project information at the planning stage - including less frequent streetwork disruptions, less From talking to our customers, we know that they environmental impact, saving money, and better want us to minimise the inconvenience of roadworks. relations with our partners and customers. Our customers see the need for roadworks to maintain and upgrade infrastructure, but they want However, sharing complicated early stage pre- planning, advance warning, co-ordination with other planning information can be very difficult. This is utilities and highway authorities, and clear information because the information often isn’t finalised yet, it’s about the roadworks and how long they’ll last. -

DW Module 17: Slow Sand Filtration Answer Key

DW Module 17: Slow Sand Filtration Answer Key Calculate the area required for a slow sand filter if it is to serve a population of 1,500 and pilot testing has indicated that the filter should be operated at a flow rate of 0.04 gpm/sq. ft. Use a projected use of 100 gpd per person and assume that there will be no industrial or commercial users. Ans: Population: 1,500 * 100 gpd/person = 150,000 gpd requirement 150,000 gpd / 1,440 minutes/day = 104 gpm 104 gpm / 0.04 gpm/sq. ft. = 2,604 sq. ft. Two filters of at least 2,604 sq. ft. will need to be constructed. Exercise Unit 1 – Exercise 1. Which of the following are filtration techniques? (Choose all that apply) a. rapid sand b. pressure c. mechanical d. chlorination e. slow sand (Answer: a., b., c., and e. ) Fill in the blank: 2. Label the following as “R” for rapid sand filter and “S” for slow sand filter. R flow rates of 2 gpm/sq. ft. or higher S during cleaning, the top layer of the schmutzdecke is scraped from the top of the filter R uses backwashing to clean the media (water flow is reversed through the filter and the backwash waste water is removed from the filter) R mechanical components consist of filter box, underdrain, surface agitator, and filter media S mechanical components consist of filter box, underdrain, and filter media S low rates of 0.04 to 0.08 gpm/ sq. ft. are common True or False: Label the following statements as “T” for True or “F” for false: 3.