Social Compass

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“Two Small Copper Coins” and Much More Chinese Protestant Women and Their Contributions to the Church – Cases from Past and Present

“Two Small Copper Coins” and Much More Chinese Protestant Women and Their Contributions to the Church – Cases from Past and Present Fredrik Fällman Introduction Observations of Christian congregations around the world, including China, will show that women make up the majority in most given settings. One could say that women have been, and are, the backbone of the Church, from the women around Jesus to the studies today that show how women make up the majority of active church members, in China as much as elsewhere. The comparative lack of male churchgoers has been discussed at length in many Churches and denominations in the West, and there have also been a number of surveys and studies trying to document and analyse this situation. Recent stud- ies also indicate that women are more religious than men in general, especially among Christians.1 In the first decades after Mao Zedong’s death the tendency towards a major- ity of older women may have been even stronger in China than in the West, since fewer younger people felt secure enough to state their faith publicly in China, or were willing to suffer the consequences in school or at work. Also, the Chinese government recognises the situa tion of a majority of women in the Church, especially in the countryside. There is even a typical Chinese phrase for this phenomenon, “lao san duo” 老三多 (three old many), i.e. Prof. Dr. Fredrik Fällman is Senior Lecturer in Chinese and Associate Head of the Department of Languages & Literatures at the University of Gothenburg in Sweden. -

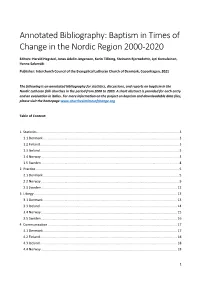

Annotated Bibliography: Baptism in Times of Change in the Nordic Region 2000-2020

Annotated Bibliography: Baptism in Times of Change in the Nordic Region 2000-2020 Editors: Harald Hegstad, Jonas Adelin Jørgensen, Karin Tillberg, Steinunn Bjornsdottir, Jyri Komulainen, Hanna Salomäki Publisher: Interchurch Council of the Evangelical Lutheran Church of Denmark, Copenhagen, 2021 The following is an annotated bibliography for statistics, discussions, and reports on baptism in the Nordic Lutheran folk churches in the period from 2000 to 2020. A short abstract is provided for each entry and an evaluation in italics. For more information on the project on baptism and downloadable data files, please visit the homepage www.churchesintimesofchange.org Table of Content: 1. Statistics ......................................................................................................................................................... 3 1.1 Denmark .................................................................................................................................................. 3 1.2 Finland ..................................................................................................................................................... 3 1.3 Iceland ..................................................................................................................................................... 3 1.4 Norway .................................................................................................................................................... 3 1.5 Sweden ................................................................................................................................................... -

Religions & Christianity in Today's

Religions & Christianity in Today's China Vol. VIII 2018 No. 3 Contents Editorial | 2 News Update on Religion and Church in China March 19 – June 30, 2018 | 3 Compiled by Katharina Wenzel-Teuber, Katharina Feith, Isabel Hess-Friemann, Jan Kwee and Gregor Weimar Religion in China: Back to the Center of Politics and Society | 28 Ian Johnson “Two Small Copper Coins” and Much More. Chinese Protestant Women and Their Contributions to the Church – Cases from Past and Present | 39 Fredrik Fällman In the Tent of Meeting: Conference on Inculturation of Catholicism in China (天主教在中国的本地化) Held in Jilin | 56 Dominic Niu Imprint – Legal Notice | 60 Religions & Christianity in Today's China, Vol. VIII, 2018, No. 3 1 Editorial Dear Readers, The third issue 2018 of Religions & Christianity in Today’s China (中国宗教评论) besides the regular News Updates on religions and especially Christianity in China contains three further articles: In his article “Religion in China: Back to the Center of Politics and Society” Ian Johnson (China correspondent of the New York Times and author of The Souls of China. The Return of Religion after Mao) describes how China is in the midst of an unprecedented religious revival with hundreds of millions of believers and thus – despite oppression in manifold ways – faith and values are returning to the center of a national discussion over how to organize Chinese life. Prof. Dr. Fredrik Fällman (Senior Lecturer in Chinese and Associate Head of the De- partment of Languages & Literatures at the University of Gothenburg in Sweden) in his contribution “‘Two Small Copper Coins’ and Much More. -

Apostolisk Succession Utredning För Missionsprovinsens Läronämnd

Missionsprovinsen i Sverige Apostolisk succession Utredning för Missionsprovinsens Läronämnd Av teol.dr. Patrik Toräng Dalby, 2014-05-15 ii Ämbetet och apostolisk succession Missionsprovinsen håller Ordets ämbete (Verbi Divini Ministerium) eller prästämbetet högt, i övertygelsen om att Herren Kristus själv har instiftat detta för sin församling. Det betyder att en prästvigning är en stor händelse i den kristna församlingen. Liksom gudstjänsten är en gemenskap med alla kristna i alla tider, så är prästvigningen ett insättande av en man i den långa raden av Ordets tjänare ända sedan apostlarnas dagar. Missionsprovinsen delar inte den romersk-katolska kyrkans ämbetssyn, vars innersta kärna är ett offerprästämbete (sacerdotium). Missionsprovinsen delar inte heller synen att vilken kristen som helst bör förvalta nådens medel i den kristna församlingen, utan hävdar att enbart den som är vigd till Ordets ämbete ska göra detta. Vi delar heller inte den synen att både män och kvinnor kan vara präster eller biskopar. Det är likaså viktigt att den som insätts i Ordets ämbete äger apostolisk tro och har tillräcklig insikt i vad det innebär att förvalta nådens medel. Genom reformationen förblev kyrkan i Sverige en episkopal kyrka, och övergick inte till att bli presbyteriansk eller kongregationalistisk. Biskopar fortsatte att vigas, och stiften behöll till stora delar sin självständighet. Eftersom Missionsprovinsen vill fullfölja det goda i Svenska kyrkans tradition, är den också formad med episkopal ordning. I begreppet episkopal ordning ingår olika moment. Kyrkan är uppbyggd med församlingar och stift, där stiftet inte bara är ett samarbetsorgan för församlingarna. Stiftet har vissa rättigheter och skyldigheter gentemot församlingarna. Till denna ordning hör också att ämbetet, prästerna under biskopens ledning och tillsyn, har vissa uppgifter, som inte kan övertas av lekfolket. -

Synod Information 2 2019

Synod Information 2 2019 - Frälsningen finns hos Herren! (Jona 2:10) * Betraktelse: Den eviga segern (OW) 1 * Tankar kring Synodstämman 2019. (LG) 2 * Lokalt: Besöka Notting Hill/ Christens gård (sr Gerd) 3 * Extra: Om Lina Sandell i Stockholm I (av III) (GI). 4 * Internationellt: Cafésamtal i London II (JN/RT) 6 * Hälsning från ordföranden. (JN) 9 * Om Extrastämman i Lund 11 maj! 10 * Ifrån S Tankesmedja: Apologetik och Bön (KS/JN) 10 * Lär känna vänstift och församling västerut. (JN) 11 * Var hittar jag andra vettiga gudstjänster m.m? 11 – Hur kan jag stötta Synodens arbete? * Förbön och gåva: Plusgiro 78 05 51-8. * Medlemsavgift 2019! 200:- (till plusgiro 780551-8). Ny medlem: maila [email protected] eller ring 072 - 931 83 42 (v.ordf). Välkommen till Extra stämma 11 maj kl 11 i Lund! Vid den kommande extrastämman presenteras ett stadgeförslag om presesråd. (Synodens årsmöte skärpte bl.a. formerna för stadgeändringar.) Ditt medlemskap gör skillnad! Många äldre har varit med länge och utgjort ryggraden till stor hjälp för många. Synoden får värdefulla gåvor för utvecklat arbete men för frågan om presesråd är ett medlemskap avgörande. Stadgeförslaget till medlem. Glöm inte medlemsavgiften 200:-! Synod Infon per post med inbetalningskort till alla intresserade utan specifik kostnad men gärna en gåva! Skriv till K Strindberg, Gröndalsvägen 110, 117 68 Stockholm. 1. Betraktelse: Den eviga segern. När Jesus dog på Golgata så vann han en evig seger. Han betalade syndens lön till sista öret. Han led istället för oss. Han blödde istället för oss. Han dog istället för oss. Fadern övergav honom istället för att överge oss (Jes 53; Ps 22:2; Matt 27:46; Mark 15:34) och han triumferade över döden när han uppstod ur graven (2 Tim 1:10). -

Concordia Theological Quarterly

Concordia Theological Quarterly Volume 78:3–4 July/October 2014 Table of Contents The Same Yesterday, Today, and Forever: Jesus as Timekeeper William C. Weinrich ............................................................................. 3 Then Let Us Keep the Festival: That Christ Be Manifest in His Saints D. Richard Stuckwisch ....................................................................... 17 The Missouri Synod and the Historical Question of Unionism and Syncretism Gerhard H. Bode Jr. ............................................................................ 39 Doctrinal Unity and Church Fellowship Roland F. Ziegler ................................................................................ 59 A Light Shining in a Dark Place: Can a Confessional Lutheran Voice Still Be Heard in the Church of Sweden? Rune Imberg ........................................................................................ 81 Cultural Differences and Church Fellowship: The Japan Lutheran Church as Case Study Naomichi Masaki ................................................................................ 93 The Christian Voice in the Civil Realm Gifford A. Grobien ............................................................................ 115 Lutheran Clichés as Theological Substitutes David P. Scaer ................................................................................... 131 Theological Observer .................................................................................... 144 Go On Inaugural Speech for the Robert D. Preus -

Choose Life! Walter Obare Omawanza

Volume 69:3-4 July/October 2005 Table of Contents The Third Use of the Law: Keeping Up to Date with an Old Issue Lawrence R. Rast .................................................................... 187 A Third Use of the Law: Is the Phrase Necessary? Lawrence M. Vogel ..................................................................191 God's Law, God's Gospel, and Their Proper Distinction: A Sure Guide Through the Moral Wasteland of Postmodernism Louis A. Smith .......................................................................... 221 The Third Use of the Law: Resolving The Tension David P. Scaer ........................................................................... 237 Changing Definitions: The Law in Formula VI James A. Nestingen ................................................................. 259 Beyond the Impasse: Re-examining the Third Use of the Law Mark C. Mattes ......................................................................... 271 Looking into the Heart of Missouri: Justification, Sanctification, and the Third Use of the Law Carl Beckwith ............................................................................ 293 Choose Life! Walter Obare Omawanza ........................................................ 309 CTQ 69 (2005): 309-326 Choose Life! Walter Obare Omwanza [The address printed below zuas deliziered by Bishop Walter Obare Omwanza of Kenya when he was called before the Council of the Lutheran World Federation to explain his participation in the consecration of Arne Olsson as Bishop of the Mission -

An Church of Kenya in the Period 1990-2005 ERLING LUNDEBY

Nr 1-2008-2:08 19-02-08 22:15 Side 43 NORSK TIDSSKRIFT FOR MISJONSVITENSKAP 1/2008 43 Structural Tensions and New Strategies Trends in Evangelical Luther - an Church of Kenya in the period 1990-2005 ERLING LUNDEBY The Evangelical Lutheran Church in Kenya (ELCK) has its origin in the mission efforts of Swedish Lutherans, later strengthened by other Scandinavian and American Lutherans. Since the start in 1948 the church for many years was limited to two-three ethnic communities in Western Kenya and Nairobi, but determined evan - gelistic efforts in the 1980s and 1990s has made ELCK of today to be a nationwide church with congregations in nearly all provinces. In many communities the church has opened up the future, provided the door to the world outside. Through its gospel message on Sundays and various community development insti - tutions it has brought temporal and eternal hope and strength for living to thousands of people. But the church has also experienced growth pains – needless to say. Missionaries played a major role in the initial stages, with varying success. Then came a period of transition with greater national participation in leadership. Although leadership was now nationalized, it was not always easy to build consensus and unity Nr 1-2008-2:08 19-02-08 22:15 Side 44 44 NORSK TIDSSKRIFT FOR MISJONSVITENSKAP 1/2008 behind the church policies and strategies. Some problems could be dealt with immediately, others were too complicated to enter into – and were postponed. As the church entered the 1990s it had reached a point where certain conflicts and financial prob - lems could no longer be ignored. -

Communion of Nordic Lutheran Dioceses

Communion of Nordic Lutheran Dioceses With this Document, The Mission Province in Sweden (Missionsprovinsen i Sverige), The Evangelical Lutheran Mission Diocese of Finland (Suomen evankelisluterilainen lähetyshiippakunta / Evangelisk- lutherska missionstiftet i Finland), and the Evangelical Lutheran Diocese in Norway (Det evangelisk- lutherske stift i Norge) declare churchly communion and mutual co-operation. Background The background for this Document consists in the church-historical reality that is based on a shared spiritual inheritance rooted in the medieval tradition of the Western Church, the Lutheran Reformation and the revivals of the recent centuries. Such a shared reality in our Dioceses can be seen, first and foremost, in our Lutheran doctrinal foundation, liturgical tradition and episcopal polity. Similarly, the three Dioceses have partaken in a similar ‘church struggle’ within the secularised Nordic mainline churches concerning questions of both Christian doctrine and ethics. The current spiritual and ecclesiastical-juridictional state of emergency has also given rise to similar solutions and actions. Divine Service communities (koinoniai) independent of the mainline churches have been founded in various places across the Nordic Countries to gather around God’s Word and the Sacrament of the Altar. For these congregations, it has been necessary to ordain new Pastors. This development has led to the birth of new, independent Dioceses in Sweden (6 September 2003), in Finland (16 March 2013) and in Norway (20 April 2013). A close -

Volume 78:3–4 July/October 2014

Concordia Theological Quarterly Volume 78:3–4 July/October 2014 Table of Contents The Same Yesterday, Today, and Forever: Jesus as Timekeeper William C. Weinrich ............................................................................. 3 Then Let Us Keep the Festival: That Christ Be Manifest in His Saints D. Richard Stuckwisch ....................................................................... 17 The Missouri Synod and the Historical Question of Unionism and Syncretism Gerhard H. Bode Jr. ............................................................................ 39 Doctrinal Unity and Church Fellowship Roland F. Ziegler ................................................................................ 59 A Light Shining in a Dark Place: Can a Confessional Lutheran Voice Still Be Heard in the Church of Sweden? Rune Imberg ........................................................................................ 81 Cultural Differences and Church Fellowship: The Japan Lutheran Church as Case Study Naomichi Masaki ................................................................................ 93 The Christian Voice in the Civil Realm Gifford A. Grobien ............................................................................ 115 Lutheran Clichés as Theological Substitutes David P. Scaer ................................................................................... 131 Theological Observer .................................................................................... 144 Go On Inaugural Speech for the Robert D. Preus -

“För Den Eviga Döden, Bevara Oss, Milde Herre Gud”

Kenneth B. Berger ”För den eviga dö- den, bevara oss, milde Herre Gud.” | 2014 Gud.” milde Herre den eviga döden, bevara oss, | ”För Kenneth Berger B. Svenskkyrklig, klassisk, bibel- och be- Kenneth B. Berger kännelsetrogen kristen tro i ljuset av kognitiva och djuppsykologiska förståel- segrunder ”För den eviga döden, bevara oss, Den här avhandlingen undersöker vissa specifika uttryck för konservativ, klassisk och bekännelsetro- milde Herre Gud.” gen kristen trostolkning och fromhet inom Svenska Svenskkyrklig, klassisk, bibel- och bekännelsetrogen kristen tro kyrkan av idag med hjälp av kognitivt motivatio- nella och djuppsykologiska närmandesätt. Den i ljuset av kognitiva och djuppsykologiska förståelsegrunder kognitiva motivationsteori som används är Uncer- tainty Orientation Theory och de djuppsykologiska närmandesätten utgörs av attachmentteorin och Terror Management Theory. Projektet är ett försök till en djupare kunskapsbase- rad förståelse av möjliga bakomliggande motiv för valet av en konservativ livsorientering och trostolk- ning. Arbetet vill erbjuda en breddad och fördjupad kun- skap om den konservativa livssynens och trosöver- tygelsens psykologiska dynamik. Metodmässigt tar denna religionspsykologiska stu- die sin utgångspunkt i ett till offentligen givet text- material skrivet av tre präster inom Svenska kyrkan, Christian Braw, Yngve Kalin och Fredrik Sidenvall, som analyseras och tolkas med en hermeneutisk metod. Arbetet hör därför till den väl etablerade traditionen av kvalitativa religionspsykologiska studier i Skandinavien. 9 789517 657549 Åbo Akademis förlag | ISBN ISBN 978-951-765-754-9 Kenneth B. Berger (f.1956 i Uppsala) Teol. kand. 1982 och fil. kand. 1983, båda forskningsförberedande, Teologiska fakulteten, Uppsala Universitet Franska statens stipendiat vid Faculté de Théologie Protestante, l’Université des Sciences Humaines de Strasbourg, 1979-1980 Verbi Divini Minister (prästvigd i Svenska kyrkan) 1992 Psykodramaregissör CP (Certified Practitioner) - i psykodrama, sociometri och gruppsykote- rapi 2013 Omslagsfoto: Rolf S. -

Detta Är Min Kropp

Detta är min kropp DANIEL ENSTEDT DETTA ÄR MIN KROPP KRISTEN TRO, SEXUALITET OCH SAMLEVNAD Skrifter utgivna vid Institutionen för litteratur, idéhistoria och religion, 41 Avhandling för filosofie doktorsexamen i religionsvetenskap, Göteborgs universitet 29 januari 2011 © Daniel Enstedt, 2011 Form & sättning: Richard Lindmark Omslagsbild: Ylva Enstedt Ralph Tryck: Intellecta Infolog AB, Kållered, 2011 ISSN 1102-9773 ISBN 978-91-88348-40-1 Distribution: Institutionen för litteratur, idéhistoria och religion, Göteborgs universitet, Box 200, 405 30 Göteborg AbsTRACT Ph.D. dissertation at University of Gothenburg, Sweden, 2011 TITLE: Detta är min kropp: Kristen tro, sexualitet och samlevnad ENGLISH TITLE: This is my Body: Christian Faith, Sexuality and Relationship AUTHOR: Daniel Enstedt LANGUAGE: Swedish, with an English summary DEPARTMENT: Department of Literature, History of Ideas and Religion, University of Gothenburg, Box 200, SE-405 30 Göteborg, Sweden SERIES: Skrifter utgivna vid Institutionen för litteratur, idéhistoria och religion, 41 ISSN 1102-9773 ISBN 978-91-88348-40-1 On October 27, 2005 the Church of Sweden introduced a special blessing for same-sex unions—a decision that was rooted in an ongoing discussion on the distinction between “ genuine” homosexuality on the one hand and “promiscuous” homosexuality on the other. Not surprisingly, the Church’s decision was welcomed by one group of adherents (e.g., LGBT Christians) and disparaged by another (e.g., protesting priests), thus underlining their diffe- ring views on the matter of sexuality, relationships and Christian faith. Using archival theories in the analysis of numerous Church documents and narratological theories in the analysis of ten protest-priest and eleven LGBT interviews, this dissertation ex- amines the development of thought that opened the way for a same-sex blessing as well as the contrasting attitudes, problems and viewpoints that have surrounded it.