Monuments, Mobility and Medieval Perceptions of Designed Landscapes: the Pleasance, Kenilworth

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Our Castle, Our Town

Our Castle, Our Town An n 2011 BACAS took part in a community project undertaken by Castle Cary investigation Museum with the purpose of exploring a selection of historic sites in and around into the the town of Castle Cary. archaeology of I Castle Cary's Using a number of non intrusive surveying methods including geophysical survey Castle site and aerial photography, the aim of the project was to develop the interpretation of some of the town’s historic sites, including the town’s castle site. A geophysical Matthew survey was undertaken at three sites, including the Castle site, the later manorial Charlton site, and a small survey 2 km south west of Castle Cary, at Dimmer. The focus of the article will be the main castle site centred in the town (see Figure 1) which will provide a brief history of the site, followed by the results of the survey and subsequent interpretation. Location and Topography Castle Cary is a small town in south east Somerset, lying within the Jurassic belt of geology, approximately at the junction of the upper lias and the inferior and upper oolites. Building stone is plentiful, and is orange to yellow in colour. This is the source of the River Cary, which now runs to the Bristol Channel via King’s Sedgemoor Drain and the River Parrett, but prior to 1793 petered out within Sedgemoor. The site occupies a natural spur formed by two conjoining, irregularly shaped mounds extending from the north east to the south west. The ground gradually rises to the north and, more steeply, to the east, and falls away to the south. -

Bibliography19802017v2.Pdf

A LIST OF PUBLICATIONS ON THE HISTORY OF WARWICKSHIRE, PUBLISHED 1980–2017 An amalgamation of annual bibliographies compiled by R.J. Chamberlaine-Brothers and published in Warwickshire History since 1980, with additions from readers. Please send details of any corrections or omissions to [email protected] The earlier material in this list was compiled from the holdings of the Warwickshire County Record Office (WCRO). Warwickshire Library and Information Service (WLIS) have supplied us with information about additions to their Local Studies material from 2013. We are very grateful to WLIS for their help, especially Ms. L. Essex and her colleagues. Please visit the WLIS local studies web pages for more detailed information about the variety of sources held: www.warwickshire.gov.uk/localstudies A separate page at the end of this list gives the history of the Library collection, parts of which are over 100 years old. Copies of most of these published works are available at WCRO or through the WLIS. The Shakespeare Birthplace Trust also holds a substantial local history library searchable at http://collections.shakespeare.org.uk/. The unpublished typescripts listed below are available at WCRO. A ABBOTT, Dorothea: Librarian in the Land Army. Privately published by the author, 1984. 70pp. Illus. ABBOTT, John: Exploring Stratford-upon-Avon: Historical Strolls Around the Town. Sigma Leisure, 1997. ACKROYD, Michael J.M.: A Guide and History of the Church of Saint Editha, Amington. Privately published by the author, 2007. 91pp. Illus. ADAMS, A.F.: see RYLATT, M., and A.F. Adams: A Harvest of History. The Life and Work of J.B. -

An Excavation in the Inner Bailey of Shrewsbury Castle

An excavation in the inner bailey of Shrewsbury Castle Nigel Baker January 2020 An excavation in the inner bailey of Shrewsbury Castle Nigel Baker BA PhD FSA MCIfA January 2020 A report to the Castle Studies Trust 1. Shrewsbury Castle: the inner bailey excavation in progress, July 2019. North to top. (Shropshire Council) Summary In May and July 2019 a two-phase archaeological investigation of the inner bailey of Shrewsbury Castle took place, supported by a grant from the Castle Studies Trust. A geophysical survey by Tiger Geo used resistivity and ground-penetrating radar to identify a hard surface under the north-west side of the inner bailey lawn and a number of features under the western rampart. A trench excavated across the lawn showed that the hard material was the flattened top of natural glacial deposits, the site having been levelled in the post-medieval period, possibly by Telford in the 1790s. The natural gravel was found to have been cut by a twelve-metre wide ditch around the base of the motte, together with pits and garden features. One pit was of late pre-Conquest date. 1 Introduction Shrewsbury Castle is situated on the isthmus, the neck, of the great loop of the river Severn containing the pre-Conquest borough of Shrewsbury, a situation akin to that of the castles at Durham and Bristol. It was in existence within three years of the Battle of Hastings and in 1069 withstood a siege mounted by local rebels against Norman rule under Edric ‘the Wild’ (Sylvaticus). It is one of the best-preserved Conquest-period shire-town earthwork castles in England, but is also one of the least well known, no excavation having previously taken place within the perimeter of the inner bailey. -

Finham Sewage Treatment Works Thermal Hydrolysis Process Plant and Biogas Upgrade Plant Variation Applications

Finham Sewage Treatment Works Thermal Hydrolysis Process Plant and Biogas Upgrade Plant Variation Applications | 0.2 July 2020 Severn Trent Water EPR/YP3995CD/V006 Thermal Hy drolysis Process Pla nt a nd Biogas Up gra de Plan t Va ria tion Ap plica tions Sever n Tr ent Wa ter Thermal Hydrolysis Process Plant and Biogas Upgrade Plant Variation Applications Finham Sewage Treatment Works Project No: Project Number Document Title: Thermal Hydrolysis Process Plant and Biogas Upgrade Plant Variation Applications Document No.: Revision: 0.2 Document Status: <DocSuitability> Date: July 2020 Client Name: Severn Trent Water Client No: EPR/YP3995CD/V006 Project Manager: Mark McAree Author: James Killick File Name: Document2 Jacobs U.K. Limited Jacobs House Shrewsbury Business Park Shrewsbury Shropshire SY2 6LG United Kingdom T +44 (0)1743 284 800 F +44 (0)1743 245 558 www.jacobs.com © Copyright 2019 Jacobs U.K. Limited. The concepts and information contained in this document are the property of Jacobs. Use or copying of this document in whole or in part without the written permission of Jacobs constitutes an infringement of copyright. Limitation: This document has been prepared on behalf of, and for the exclusive use of Jacobs’ client, and is subject to, and issued in accordance with, the provisions of the contract between Jacobs and the client. Jacobs accepts no liability or responsibility whatsoever for, or in respect of, any use of, or reliance upon, this document by any third party. Document history and status Revision Date Description Author Checked Reviewed Approved i Thermal Hydrolysis Process Plant and Biogas Upgrade Plant Variation Applications Contents Non-Technical Summary.................................................................................................................................................. -

Castle& Abbey Trail

Getting here: Castle & Abbey Trail Kenilworth Castle by Jamie Gray Photography By Car By Train elcome to Kenilworth, a place most definitely worth Kenilworth is located on the Trains run regularly from your time…. Step into our monumental story amongst A46 just 6 miles from both Kenilworth Station to Coventry W the noble ruins of Kenilworth Castle. Lose yourself Coventry and Warwick. and Royal Leamington Spa. in the rolling greenery of Abbey Fields, or venture just a little further into beautiful countryside alive with nature. Spend a day There is plenty of parking in www.nationalrail.co.uk uncovering the rich threads of our history, browse intriguing the town centre at Abbey End. shops or simply kick back over some fabulous food & drink. By Foot or By Bike By Bus But wait, there’s more here than you’d think So, slow down, The Kenilworth Greenway savour each moment and... Regular services connect connects to Berkswell and Kenilworth with Warwick, the Centenary and Millennium Royal Leamington Spa and Ways pass through the town. Discover the story for yourself... Coventry. www.warwickshire.gov.uk/ www.traveline.info pathsandtrails Further Information: Visit visit.kenilworthweb.co.uk for more information Visit www.shakespeares-england.co.uk for information on the wider area Lapidarium Wall in Abbey Ruins by James Turner Want a deeper experience? Kenilworth Town Council Discover Kenilworth’s This leaflet is just the tip of the iceberg! We have also developed a companion greatest story! mobile website which expands on each of These trails were produced by Kenilworth Town Council, and were our trails, with bags more information and funded by a grant from HS2’s Business & Local Economy Fund (BLEF), adding benefit to communities demonstrably disrupted by the 3.5 Miles Approx. -

Nissan Figaro 30Th Birthday Party Weekend 2021 All Tours Will Leave from the Venue Hotel Walton Hall Hotel & Spa

Nissan Figaro 30th Birthday Party Weekend 2021 All tours will leave from the Venue Hotel Walton Hall Hotel & Spa STONELEIGH TOUR Schedule Saturday 26th June 2021 09.30 Meet in the Hotel Reception 09.45 Depart Hotel and drive to start point (19 Kms) - AGree who will lead the convoy Start Point - 69 St Johns Car ParK, WarwicK, CV34 4NL Tour Route Distance – 75 Kms Route to start point from Hotel Head north-west on Kineton Rd/B4086 towards Jubilee Dr 1.57 km Turn right onto Newbold Rd/B4087Continue to follow B4087 5.82 Km Turn left onto Banbury Rd/B4100Continue to follow Banbury Rd 2.20 Km At the roundabout, take the 2nd exit onto Banbury Rd/A425 3.37 km Turn right 225 m 69 St Johns Ct, WarwicK CV34 4NL, UK THIS IS WHERE THE TOUR STARTS The Stoneleigh tour starts from St Nicholas’ Park in Warwick and takes you through the historic town and the north of Royal Leamington Spa. It then leads you through the rolling countryside and picturesque villages of central Warwickshire and the market town of Southam before heading north to take in Stoneleigh and Kenilworth. It returns via Honiley and the craft and antiques centre at Hatton Country World – before bringing you back past the Racecourse into Warwick. The historic town of Warwick is well worth exploring. Here you can browse antique, china and gift shops and visit a number of museums. For refreshment there are some good pubs, fine restaurants and tearooms in the town. Leaving the car park at St Nicholas’ Park in Warwick, turn right onto the A425 signed Birmingham. -

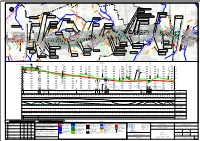

INTERNAL C223-CSI-CV-DPP-030-000005 P11 Rev Description Drawn Checked Con App HS2 App

@ 1:10000 Rev P08 P09 P07 P10 P11 METRES 1 3 0 . 0 m m 0 . 0 3 m 1 0 . 1 m 3 0 Revised InterimConditionB Revised InterimConditionB Issued forCP3 Issued forCP3 Fit forhybridbillsubmission Condition B.Code1. 0 .0 . 3 0 0 m 1 13 0 1 3 0 . 0 m 100 0m 0. 13 BEECHWOOD Description 200 .0m 130.0m 130 130.0m 146-S2 CromwellLaneReinstatement 130.0m 130 .0m .0m 130 100 110 120 130 70 80 90 30 40 50 60 147+000 500 29/08/13 21/10/13 28/10/13 29/11/13 17/12/13 Drawn NOR NOR NOR NOR RPH km/h 400 -7.7 117.4 125.1 146+700 m 0 . 0 2 1 Checked 29/08/13 16/10/13 28/10/13 29/11/13 17/12/13 -8.2 117.0 125.2 146+600 MSB GW GW GW G PD L 146-L1 BurtonGreenTunnel = = For Continuation Refer Burton Green 0 To Dr 1 awing C223-CSI-CV-DPP-030-000 . 006 4 North Portal 3 1 Footpath M182 -9.6 116.6 126.2 7 146+500 5 % Con App 1 1 29/08/13 16/10/13 28/10/13 29/11/13 17/12/13 m 3 0 . 3 0 0 3 0 1 . 0 . 0 m 3 m m 0 . PD PD PD PD PD 0 m 3 0 . 0 3 1 1 360km/h m 0 . -9.9 116.3 126.2 146+400 0 3 BURTON 1 Cromwell Lane 1 GREEN 3 0 . -

Portchester Castle Student Activity Sheets

STUDENT ACTIVITY SHEETS Portchester Castle This resource has been designed to help students step into the story of Portchester Castle, which provides essential insight into over 1,700 years of history. It was a Roman fort, a Saxon stronghold, a royal castle and eventually a prison. Give these activity sheets to students on site to help them explore Portchester Castle. Get in touch with our Education Booking Team: 0370 333 0606 [email protected] https://bookings.english-heritage.org.uk/education Don’t forget to download our Hazard Information Sheets and Discovery Visit Risk Assessments to help with planning: • In the Footsteps of Kings • Big History: From Dominant Castle to Hidden Fort Share your visit with us @EHEducation The English Heritage Trust is a charity, no. 1140351, and a company, no. 07447221, registered in England. All images are copyright of English Heritage or Historic England unless otherwise stated. Published July 2017 Portchester Castle is over 1,700 years old! It was a Roman fort, a Saxon stronghold, a royal palace and eventually a prison. Its commanding location means it has played a major part in defending Portsmouth Harbour EXPLORE and the Solent for hundreds of years. THE CASTLE DISCOVER OUR TOP 10 Explore the castle in small groups. THINGS TO SEE Complete the challenges to find out about Portchester’s exciting past. 1 ROMAN WALLS These walls were built between AD 285 and 290 by a Roman naval commander called Carausius. He was in charge of protecting this bit of the coast from pirate attacks. The walls’ core is made from layers of flint, bonded together with mortar. -

Locality Profile January 2011 Locality Name: Kenilworth District: Warwick District

Sustainability Appraisal Scoping Report Appendix 3 – Background Technical Paper – Locality Profiles Locality Profile January 2011 Locality Name: Kenilworth District: Warwick District The Kenilworth locality comprises the wards of Abbey, St John’s, Park Hill, a small area of Stoneleigh and the village of Burton Green. It includes the 3 County Council Electoral Divisions of Kenilworth held by 3 County Councillors. 9 District Councillors represent the town, and the Town Council is made up of 16 Councillors. Aside from the town centre and residential areas, the locality is rural and sparsely populated. Part of the University of Warwick campus falls into the north-east part of the locality. Kenilworth Castle is a popular tourist attraction. Population Households2 Locality Warwickshire Locality Warwickshire No. % No. % No. % No. % Total Population (Mid-2009)¹ 25,532 - 535,100 - Total Resident Households 10,468 - 210,898 - Male/Female Split¹ 49/51 - 49/51 - Average Household Size 2.30 - 2.37 - Total 0-15 year olds¹ 4,246 16.6% 97,800 18.3% Socially Rented Housing 710 6.8% 30,196 14.3% Total Working Age* 15,104 59.2% 323,900 60.5% Terraced Housing 1,737 16.6% 51,458 23.6% Population¹ Total 65+ Males, 60+ 6,183 24.2% 113,400 21.2% Households with no car/van 1,466 14.0% 40,130 19.0% Females*¹ Non-White British Population² 1,847 7.5% 36,553 7.2% Urban/Rural Population Split³ 100/0 - 68/32 - * 16-64 Males, 16-59 Females Economy & Employment Low Income Households6 Locality Warwickshire Locality Warwickshire No. -

Castelli Di Bellinzona

Trenino Artù -design.net Key Escape Room Torre Nera La Torre Nera di Castelgrande vi aspetta per vivere una entusiasmante espe- rienza e un fantastico viaggio nel tempo! Codici, indizi e oggetti misteriosi che vi daranno la libertà! Una Room ambientata in una location suggestiva, circondati da 700 anni di storia! Prenotate subito la vostra avventura medievale su www.blockati.ch Escape Room Torre Nera C Im Turm von Castelgrande auch “Torre Nera” genannt, kannst du ein aufre- gendes Erlebnis und eine unglaubliche Zeitreise erleben! Codes, Hinweise M und mysteriöse Objekte entschlüsseln, die dir die Freiheit geben! Ein Raum in Y einer anziehender Lage, umgeben von 700 Jahren Geschichte! CM Buchen Sie jetzt Ihr mittelalterliches Abenteuer auf www.blockati.ch MY Escape Room Tour Noire CY La Tour Noire de Castelgrande, vous attends pour vivre une expérience pas- CMY sionnante et un voyage fantastique dans le temps ! Des codes, des indices et des objets mystérieux vous donneront la liberté! Une salle dans un lieu Preise / Prix / Prices Orari / Fahrplan / Horaire / Timetable K évocateur, entouré de 700 ans d’histoire ! Piazza Collegiata Partenza / Abfahrt / Lieu de départ / Departure Réservez votre aventure médiévale dès maintenant sur www.blockati.ch Trenino Artù aprile-novembre Do – Ve / So – Fr / Di – Ve / Su – Fr 10.00 / 11.20 / 13.30 / 15.00 / 16.30 Adulti 12.– Piazza Governo Partenza / Abfahrt / Lieu de départ / Departure Escape Room Black Tower Sa 11.20 / 13.30 The Black Tower of Castelgrande, to live an exciting experience and a fan- Ridotti Piazza Collegiata Partenza / Abfahrt / Lieu de départ / Departure tastic journey through time! Codes, clues and mysterious objects that will Senior (+65), studenti e ragazzi 6 – 16 anni 10.– Sa 15.00 / 16.30 give you freedom! A Room set in an evocative location, surrounded by 700 a Castelgrande, years of history! Gruppi (min. -

Tarbert Castle

TARBERT CASTLE EXCAVATION PROJECT DESIGN March 2018 Roderick Regan Tarbert Castle: Our Castle of Kings A Community Archaeological Excavation. Many questions remain as to the origin of Tarbert castle, its development and its layout, while the function of many of its component features remain unclear. Also unclear is whether the remains of medieval royal burgh extend along the ridge to the south of the castle. A programme of community archaeological excavation would answer some of these questions, leading to a better interpretation, presentation and future protection of the castle, while promoting the castle as an important place through generated publicity and the excitement of local involvement. Several areas within the castle itself readily suggest areas of potential investigation, particularly the building ranges lining the inner bailey and the presumed entrance into the outer bailey. Beyond the castle to the south are evidence of ditches and terracing while anomalies detected during a previous geophysical survey suggest further fruitful areas of investigation, which might help establish the presence of the putative medieval burgh. A programme of archaeology involving the community of Tarbert would not only shed light on this important medieval monument but would help to ensure it remained a ‘very centrical place’ in the future. Kilmartin Museum Argyll, PA31 8RQ Tel: 01546 510 278 Email: http://www.kilmartin.org © 2018 Kilmartin Museum Company Ltd SC 022744. Kilmartin House Trading Co. Ltd. SC 166302 (Scotland) ii Contents 1. Introduction 1 2. Tarbert Castle 5 2.1 Location and Topography 5 2.2 Historical Background 5 3 Archaeological and Background 5 3.1 Laser Survey 6 3.2 Geophysical Survey 6 3.3 Ground and Photographic Survey 6 3.4 Excavation 7 3.5 Watching Brief 7 3.6 Recorded Artefacts 7 4. -

Lindsview 43A High Street Kenilworth

Lindsview 43A High Street Kenilworth Lindsview, 43A High Street Kenilworth An impressive family home located in a prime position on the High Street in Kenilworth, with spectacular views over Abbey Fields. Kenilworth town centre 0.5 mile, Warwick University 2.5 miles, Coventry 5 miles (intercity trains to London Euston from 59 minutes), Warwick 5 miles, Warwick Parkway Station 6 miles (trains to London Marylebone from 69 minutes), Leamington Spa 6 miles, M40 (J15) 8 miles, Birmingham International Airport 11 miles, Stratford upon Avon 14 miles (distances and times approximate) Situation Lindsview is situated on Kenilworth High Street in the 4/5 3/4 3 conservation area of Old Town Kenilworth. The property is a short walk from Kenilworth Castle, Abbey Fields and some excellent restaurants and gastro pubs are close by. Kenilworth is a small historic town in the heart of Warwickshire having a wide range of shops, including a Waitrose, restaurants and sports facilities. The Warwickshire Golf and Country Club is located 5 miles away. The property is well placed for motorway and rail networks and Birmingham Airport. There is a train station in the town which is within walking distance, providing direct links to Coventry and Leamington Spa, with connections to London and Birmingham. The area is well served by a range of state, grammar and private schools including Crackley Hall in Kenilworth, King Henry VIII and Bablake in Coventry, Warwick School for Boys and King’s High School for Girls in Warwick, Kingsley School for Girls and Arnold Lodge School in Leamington Spa. Description of property This beautiful detached family home has a unrivalled position overlooking Abbey Fields and was built by the current owners approximately 20 years ago, occupying 0.3 of an acre.