Download Download

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Life and Travels of John Bartram (1699-1777), „His Majesty´S Botanist for North America“, and His Sons Isaac, Moses and William

The Life and Travels of John Bartram (1699-1777), „His Majesty´s Botanist for North America“, and his Sons Isaac, Moses and William Holger Goetzendorff, Pulheim (Alemania) [email protected] John Bartram, a Quaker, came from Derbyshire, England and settled 1681 in America. He had established himself as one of the leaders of the new community of Darby Creek near Philadelphia. He had five children among them William who was the father of the future botanist John. John Bartram John received the average education in a Quaker school. By the time he reached twelve years, his interest developed to ‚Physick ‛ and surgery and later to ‚Botanicks ‛. In 1709 his father William moved to Carolina. There was a lot of trouble between the indians and the white settlers, some of their land had been purchased, but much had simply been taken. 22.9.1711: Indians attacked the area and William was killed. His second wife and the children were taken prisoners for half a year. John Bartram and Mary Maris were maried 1722. Their son Isaac was born in 1724. She died five years later in 1727. 1728 John Bartram purchased land at Kingsessing near Philadelphia. One year later John Bartram and his second wife Ann Mendenhall were married. Residence of John Bartram, built in 1730 John built a house on his farm which is still standing today. The farm behind the house was accompanied by a large garden and one of the first botanical gardens in America. He bought a lot of land round the farm and in Philadelphia where he built houses. -

Thomas Say and Thoreau’S Entomology

THOMAS SAY AND THOREAU’S ENTOMOLOGY “Entomology extends the limits of being in a new direction, so that I walk in nature with a sense of greater space and freedom. It suggests besides, that the universe is not rough-hewn, but perfect in its details. Nature will bear the closest inspection; she invites us to lay our eye level with the smallest leaf, and take an insect view of its plain. She has no interstices; every part is full of life. I explore, too, with pleasure, the sources of the myriad sounds which crowd the summer noon, and which seem the very grain and stuff of which eternity is made. Who does not remember the shrill roll-call of the harvest fly? ANACREON There were ears for these sounds in Greece long ago, as Anacreon’s ode will show” — Henry Thoreau “Natural History of Massachusetts” July 1842 issue of The Dial1 “There is as much to be discovered and to astonish in magnifying an insect as a star.” — Dr. Thaddeus William Harris 1. Franklin Benjamin Sanborn reported that “one of Harvard College’s natural historians” (we may presume this to have been Dr. Thaddeus William Harris, Thoreau’s teacher in natural science in his senior year) had remarked to Bronson Alcott that “if Emerson had not spoiled him, Thoreau would have made a good entomologist.” HDT WHAT? INDEX THOMAS SAY AND THOREAU’S ENTOMOLOGY “NARRATIVE HISTORY” AMOUNTS TO FABULATION, THE REAL STUFF BEING MERE CHRONOLOGY “Stack of the Artist of Kouroo” Project Thomas Say and Thoreau’s Entomology HDT WHAT? INDEX THOMAS SAY AND THOREAU’S ENTOMOLOGY 1690 8mo 5-31: Friend William Say and Friend Mary Guest (daughter of the widow Guest) posted their bans and became a married couple in the Burlington, New Jersey monthly meeting of the Religious Society of Friends, across the river from Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. -

![Science at Engineer Cantonment [Part 5] Hugh H](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9168/science-at-engineer-cantonment-part-5-hugh-h-799168.webp)

Science at Engineer Cantonment [Part 5] Hugh H

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Mammalogy Papers: University of Nebraska State Museum, University of Nebraska State Museum Spring 2018 Science at Engineer Cantonment [Part 5] Hugh H. Genoways University of Nebraska - Lincoln, [email protected] Brett .C Ratcliffe University of Nebraska - Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/museummammalogy Genoways, Hugh H. and Ratcliffe, Brett .,C "Science at Engineer Cantonment [Part 5]" (2018). Mammalogy Papers: University of Nebraska State Museum. 279. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/museummammalogy/279 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Museum, University of Nebraska State at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Mammalogy Papers: University of Nebraska State Museum by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Part 5 Science at Engineer Cantonment HUGH H. GENOWAYS AND BRETT C. RATCLIFFE Introduction ong’s Expedition was the first party with trained scientists to explore the American LWest in the name of the United States government.1 Historians have not been particularly kind to the expedition. William Goetzmann described the party as “A curious cavalcade of disgruntled career officers, eccentric scientists, and artist-playboys, . .”2 Hiram Chittenden believed that the expedition of 1819 had failed, and that “a small side show was organized for the season of 1820 in the form of an expedition to the Rocky Mountains.”3 On the other hand, biologists have had a much more positive view of the expedition’s results.4 However, biologists have concentrated their interest, not surprisingly, on the summer expedition, because members of the party were Many new taxa of plants and animals were the first to study and collect in the foothills of the discovered in the vicinity of the cantonment. -

Colorado Field Ornithologists

N0.7 WINTER 1970 the Colorado Field Ornithologist SPECIAL ISSUE JOINT MEETING COLORADO FIELD ORNITHOLOGISTS 8th Annual Meeting COOPER ORNITHOLOGICAL SOCIETY 41 st 'Annual Meeting WILSON ORNITHOLOGICAL SOCIETY 51 st Annual Meeting FORT COLLINS, COLORADO June 18 - 21, 1970 WINTER, 1970 No, 7 IN THIS ISSUE: Page ORNITHOLOGY AND GEOGRAPHY IN COLORADO George R. Shier • 1 SUMMER BIRD-FINDING IN COLORADO Donald M. Thatcher 5 BIRD CLUBS IN COLORADO David W, Lupton • 11 THE FOUNDERS OF COLORADO ORNITHOLOGY Thomps.on G. Marsh • 16 COLORADO TYPE BIRD LOCALITIES Harold R. Holt 18 SURVEY OF COLLECTIONS OF BIRDS IN COLORADO Donald W. Janes •.•.• 23 RESEARCH THROUGH BIRD BANDING IN COLORADO Allegra Collister • • • • • 26 The Colorado Field Ornithologist is a semiannual journal devoted to the field study of birds in Colorado. Articl~s and notes of scientific or general interest, and reports of unusual observations are solicited, Send manu scripts, with photos and drawings, to D. W. Lupton, Editor, Serials Section, Colorado State University Libraries, Fort Collins, Colorado 80521. Membership and subscription fees: Full member $3.00; Library subscription fees $1.50. Submit payments to Robbie Elliott, Executive Secretary , The Colorado Field Ornithologist, 220-3lst Street, Boulder, Colorado 80303. Request for exchange or for back numbers should be addressed to the Editor. All exchange publications should likewise be sent to the Editor's address. I WINTER, 1970 No. 7 ORNITHOLOGY AND GEOGRAPHY IN COLORADO George R. Shier Golden, Colorado Colorado is divided into many climatic and geographic provinces. In this brief article only a few representative locations can be mentioned. The northeast holds the rich irrigated South Platte Valley. -

Engineer Cantonment, Missouri Territory, 1819-1820: America's First Biodiversity Ineventory

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Great Plains Research: A Journal of Natural and Social Sciences Great Plains Studies, Center for 2008 Engineer Cantonment, Missouri Territory, 1819-1820: America's First Biodiversity Ineventory Hugh H. Genoways University of Nebraska - Lincoln, [email protected] Brett C. Ratcliffe University of Nebraska - Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/greatplainsresearch Part of the Other International and Area Studies Commons, Plant Sciences Commons, and the Zoology Commons Genoways, Hugh H. and Ratcliffe, Brett C., "Engineer Cantonment, Missouri Territory, 1819-1820: America's First Biodiversity Ineventory" (2008). Great Plains Research: A Journal of Natural and Social Sciences. 927. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/greatplainsresearch/927 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Great Plains Studies, Center for at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Great Plains Research: A Journal of Natural and Social Sciences by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Great Plains Research 18 (Spring 2008):3-31 © 2008 Copyright by the Center for Great Plains Studies, University of Nebraska-Lincoln ENGINEER CANTONMENT, MISSOURI TERRITORY, 1819-1820: AMERICA'S FIRST BIODIVERSITY INVENTORY Hugh H. Genoways and Brett C. Ratcliffe Systematic Research Collections University o/Nebraska State Museum Lincoln, NE 68588-0514 [email protected] and [email protected] ABSTRACT-It is our thesis that members of the Stephen Long Expedition of 1819-20 completed the first biodiversity inventory undertaken in the United States at their winter quarters, Engineer Cantonment, Mis souri Territory, in the modern state of Nebraska. -

Biblioqraphy & Natural History

BIBLIOQRAPHY & NATURAL HISTORY Essays presented at a Conference convened in June 1964 by Thomas R. Buckman Lawrence, Kansas 1966 University of Kansas Libraries University of Kansas Publications Library Series, 27 Copyright 1966 by the University of Kansas Libraries Library of Congress Catalog Card number: 66-64215 Printed in Lawrence, Kansas, U.S.A., by the University of Kansas Printing Service. Introduction The purpose of this group of essays and formal papers is to focus attention on some aspects of bibliography in the service of natural history, and possibly to stimulate further studies which may be of mutual usefulness to biologists and historians of science, and also to librarians and museum curators. Bibli• ography is interpreted rather broadly to include botanical illustration. Further, the intent and style of the contributions reflects the occasion—a meeting of bookmen, scientists and scholars assembled not only to discuss specific examples of the uses of books and manuscripts in the natural sciences, but also to consider some other related matters in a spirit of wit and congeniality. Thus we hope in this volume, as in the conference itself, both to inform and to please. When Edwin Wolf, 2nd, Librarian of the Library Company of Phila• delphia, and then Chairman of the Rare Books Section of the Association of College and Research Libraries, asked me to plan the Section's program for its session in Lawrence, June 25-27, 1964, we agreed immediately on a theme. With few exceptions, we noted, the bibliography of natural history has received little attention in this country, and yet it is indispensable to many biologists and to historians of the natural sciences. -

Copyrighted Material

1 1 Introduction – A Brief History of Revolutions in the Study of Insect Biodiversity Peter H. Adler1 and Robert G. Foottit2 1 Department of Plant and Environmental Sciences, Clemson University, Clemson, South Carolina, USA 2 Canadian National Collection of Insects, Arachnids, and Nematodes, Agriculture and Agri‐Food Canada, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada John Platt (1964), in his iconic paper “Strong Hennig’s procedural framework for inferring Inference,” asked “Why should there be such relationships. The revolutions of significance rapid advances in some fields and not in in understanding biodiversity (Fig. 1.1) have, others?” The answer, he suggested, was that therefore, largely been those that enabled and “Certain systematic methods of scientific enhanced (i) the discovery process, (ii) the con thinking may produce much more rapid pro ceptual framework, and (iii) the management of gress than others.” As a corollary to Platt’s information. (1964) query, we ask “Why, within a field, should there be such rapid advances at some times and not at others?” The answer, we sug 1.1 Discovery gest, is “revolutions” – revolutions in thinking and technology. Perhaps the most revolutionary of all the devel In the study of life’s diversity, what were the opments that enabled the discovery of insect revolutions that brought us to a 21st‐century biodiversity was the light microscope, invented understanding of its largest component – the in the 16th century. The first microscopically insects? Some revolutions were taxon specific, viewed images of insects, a bee and a weevil, such as the linkage of diseases to vectors were published in 1630 (Stelluti 1630). -

Peter Dances Books 1

DELIGHTS FOR THE EYES AND THE MIND A brief survey of conchological books by S. Peter Dance Many years ago virtually every English town of any size supported at least one or two second-hand book- shops. It was still possible to find wonderful things lying neglected on their dusty shelves or on their even dustier floors. Such shops had an irresistible allure for the impecunious youth with a liking for natural history books that I was then. How well I remember the day when I wandered around one of these magical caves and carried off, for the princely sum of two shillings and sixpence, my first shell book, a copy of Jacques Philippe Raymond Draparnaud's Histoire Naturelle des Mollusques terrestres et fluviatiles de la France. Published in 1805 but still in pristine condition, written by a pioneer of European conchology, containing engraved plates of shells, it had been delicately annotated in pencil by a former owner, Sylvanus Hanley. The most exotic purchase I had ever made, I sensed then that it was an almost perfect acquisition for the dedicated collector of such things, for it was old and in fine condition, was illustrated (albeit not in colour), contained interesting annotations by a former owner who had himself acquired a degree of fame in the conchological world, and was a bargain at the price. Half a century later I know that it will be very difficult to repeat so satisfying a transaction for so small an outlay but interesting items will still come onto the market to tempt discerning purchasers. -

Download Full Article in PDF Format

geodiversitas 2021 43 1 e of lif pal A eo – - e h g e r a p R e t e o d l o u g a l i s C - t – n a M e J e l m a i r o DIRECTEUR DE LA PUBLICATION / PUBLICATION DIRECTOR : Bruno David, Président du Muséum national d’Histoire naturelle RÉDACTEUR EN CHEF / EDITOR-IN-CHIEF : Didier Merle ASSISTANT DE RÉDACTION / ASSISTANT EDITOR : Emmanuel Côtez ([email protected]) MISE EN PAGE / PAGE LAYOUT : Emmanuel Côtez COMITÉ SCIENTIFIQUE / SCIENTIFIC BOARD : Christine Argot (Muséum national d’Histoire naturelle, Paris) Beatrix Azanza (Museo Nacional de Ciencias Naturales, Madrid) Raymond L. Bernor (Howard University, Washington DC) Alain Blieck (chercheur CNRS retraité, Haubourdin) Henning Blom (Uppsala University) Jean Broutin (Sorbonne Université, Paris, retraité) Gaël Clément (Muséum national d’Histoire naturelle, Paris) Ted Daeschler (Academy of Natural Sciences, Philadelphie) Bruno David (Muséum national d’Histoire naturelle, Paris) Gregory D. Edgecombe (The Natural History Museum, Londres) Ursula Göhlich (Natural History Museum Vienna) Jin Meng (American Museum of Natural History, New York) Brigitte Meyer-Berthaud (CIRAD, Montpellier) Zhu Min (Chinese Academy of Sciences, Pékin) Isabelle Rouget (Muséum national d’Histoire naturelle, Paris) Sevket Sen (Muséum national d’Histoire naturelle, Paris, retraité) Stanislav Štamberg (Museum of Eastern Bohemia, Hradec Králové) Paul Taylor (The Natural History Museum, Londres, retraité) COUVERTURE / COVER : Réalisée à partir des Figures de l’article/Made from the Figures of the article. Geodiversitas est -

Bibliography of Biographies of Entomologists Italicizedletters A-Anonymous, B=Bibliography, P=Portrait

The AmericanMidland Naturalist PublishedBi-Monthly by The Universityof Notre Dame, NotreDame, Indiana VOL. 33 JANUARY, 1945 No. 1 Bibliographyof Biographiesof Entomologists* Mathilde M. Carpenter For more than fifteenyears the excellent "Bibliography of Entomologists" prepared by Mr. J. S. Wade, Ann. Ent. Soc. Amer., 21:489-520, 1928, has proved of great value to all who have an interest in the development of the science. The time seems ripe for what might be called a second edition of the work, one which will bring the subject up to date and which at the same time will enlarge its scope to include the records of biographical matter for all entomologists of all countries. It is intended that the list will be complete through 1943. The work was undertaken because of frequent inquiries about more or less inaccessible biographical data, and has been carried out in spare time for several years. All the leading entomological periodicals and many other sources have been consulted. The referencesinclude not only obituaries, but birthdays, portraits, anniversaries,biographies and disposition of collections. As regards the last named item, the writer regrets that the italicized C could not have been placed before a referenceto indicate the disposal and present location of a collection, but the realization of its importance came too late to be utilized. However, such information of all important insect collections up to 1937 can be found in an extensive paper by Walther Horn and Ilse Kahle in Entomologische Beihefte aus Berlin-Dahlem, 2:1-160, 1935; 3:161-296, 1936; 4:297-388, 1937. Mistakes and omissions undoubtedly occur. -

Colorado Field Ornithologists the Colorado Field Ornithologists' Quarterly

Journal of the Colorado Field Ornithologists The Colorado Field Ornithologists' Quarterly VOL. 33, NO. 1 Journal of the Colorado Field Ornithologists January 1999 JOURNAL OF THE COLORADO FIELD ORNITHOLOGISTS (USPS 0446-190) (ISSN 1094- 0030) is published quarterly by the Colorado Field Ornithologists, 3410 Heidelberg Drive, Boulder, CO 80303-7016. Subscriptions are obtained through annual membership dues. Periodicals postage paid at Boulder, CO. POSTMASTER: Send address changes to Journal of the Colorado Field Ornithologists, P.O. Box 481, Lyons, CO 80540-0481. OFFICERS OF THE COLORADO FIELD ORNITHOLOGISTS: Dates indicate end of current term. An asterisk indicates eligibility for re-election. President: Leon Bright, 636 Henry Ave., Pueblo, CO 81005; 719/561-1108; [email protected]; 1999* Past-President: Linda Vidal, 1305 Snowbunny Ln., Aspen, CO 81611; 970/925-7134; [email protected] Vice-President: William Fink, 1225 Columbia Dr., Longmont, CO 80503; 303/776-7395; 1999* Secretary: Toni Brevillier, 2616 Ashgrove St., Colorado Springs, CO 80906; 719/540-5653; [email protected]; 1999* Treasurer: BB Hahn, 2915 Hodgen Rd., Black Forest, CO 80921 ; 719/495-0647; [email protected]; 1999* Directors: Raymond Davis, Lyons, 303/823-5332, 1999*; Pearle Sandstrom-Smith, Pueblo, 719/ 543-6427, 1999*; Warren Finch, Lakewood, 303/233-3372, 2000* ; Jameson Chace, Boulder, 303/492-6685, 2001 *; Richard Levad, Grand Junction, 970/242-3979, 2001 *; Suzi Plooster, Boulder, 303/494-6708, 2001; Robert Spencer, Golden, 303/279-4682, 2001 *;Mark Yeager, Pueblo, 719/545-8407, 2001 * Journal Staff Cynthia Melcher (Editor), 4200 North Shields, Fort Collins, CO 80524, 970/484- 8373, [email protected]; Beth Dillon (Associate Editor); Mona Hill (Administrative Editoral Assistant); Jameson Chace and Richard Harness (Science Editors). -

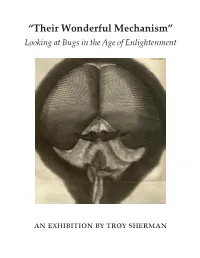

“Their Wonderful Mechanism” Looking at Bugs in the Age of Enlightenment

“Their Wonderful Mechanism” Looking at Bugs in the Age of Enlightenment an exhibition by troy sherman But as mankind became more enlightened, the great wonders of nature in these small animals began to be observed . carolus linnaeus, Fundamenta Entomologiae, 1772 Cover art from robert hooke, Micrographia, 1665 “Their Wonderful Mechanism” Looking at Bugs in the Age of Enlightenment HEN ROBERT HOOKE peered Williams College and organized in three through his microscope into the sections corresponding to the body segments of Weyes of a dronefly, he didn’t simply catch an insect, demonstrates how scientific discourse the bug peering back: concerning bugs he saw his world converged with and reflected in its gaze. helped shape empirical Within each pane of methodologies and the insect’s compound technologies, colonial eyes, wrote Hooke in expansion, and 1666, “I have been able political thought to discover a Land- during western scape of those things Europe’s age of which lay before my Enlightenment. window.” In Hooke’s Hooke’s observa- study, the dronefly’s tion dramatizes the play eyes not only served as between knowledge and experimental material culture at an important to demonstrate the stage in the history of observational capacity entomology: in the 17th of his microscope, and 18th centuries, as but also provided a robert hooke, Micrographia, 1665 European natural philosophers visually captivating turned unprecedented amounts of their metaphor for the new technology. Hooke’s attention towards insect life, bugs in turn experiment indexes a shift of empirical contributed to shaping the new ways that interest towards the study of bugs rooted in these scientists were describing their world.