Tracing Biometric Assemblages in India's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reg. No Name in Full Residential Address Gender Contact No

Reg. No Name in Full Residential Address Gender Contact No. Email id Remarks 20001 MUDKONDWAR SHRUTIKA HOSPITAL, TAHSIL Male 9420020369 [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 PRASHANT NAMDEORAO OFFICE ROAD, AT/P/TAL- GEORAI, 431127 BEED Maharashtra 20002 RADHIKA BABURAJ FLAT NO.10-E, ABAD MAINE Female 9886745848 / [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 PLAZA OPP.CMFRI, MARINE 8281300696 DRIVE, KOCHI, KERALA 682018 Kerela 20003 KULKARNI VAISHALI HARISH CHANDRA RESEARCH Female 0532 2274022 / [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 MADHUKAR INSTITUTE, CHHATNAG ROAD, 8874709114 JHUSI, ALLAHABAD 211019 ALLAHABAD Uttar Pradesh 20004 BICHU VAISHALI 6, KOLABA HOUSE, BPT OFFICENT Female 022 22182011 / NOT RENEW SHRIRANG QUARTERS, DUMYANE RD., 9819791683 COLABA 400005 MUMBAI Maharashtra 20005 DOSHI DOLLY MAHENDRA 7-A, PUTLIBAI BHAVAN, ZAVER Female 9892399719 [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 ROAD, MULUND (W) 400080 MUMBAI Maharashtra 20006 PRABHU SAYALI GAJANAN F1,CHINTAMANI PLAZA, KUDAL Female 02362 223223 / [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 OPP POLICE STATION,MAIN ROAD 9422434365 KUDAL 416520 SINDHUDURG Maharashtra 20007 RUKADIKAR WAHEEDA 385/B, ALISHAN BUILDING, Female 9890346988 DR.NAUSHAD.INAMDAR@GMA RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 BABASAHEB MHAISAL VES, PANCHIL NAGAR, IL.COM MEHDHE PLOT- 13, MIRAJ 416410 SANGLI Maharashtra 20008 GHORPADE TEJAL A-7 / A-8, SHIVSHAKTI APT., Male 02312650525 / NOT RENEW CHANDRAHAS GIANT HOUSE, SARLAKSHAN 9226377667 PARK KOLHAPUR Maharashtra 20009 JAIN MAMTA -

Missing Lawyer at Risk of Torture

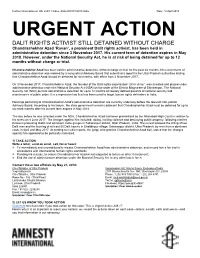

Further information on UA: 248/17 Index: ASA 20/8191/2018 India Date: 10 April 2018 URGENT ACTION DALIT RIGHTS ACTIVIST STILL DETAINED WITHOUT CHARGE Chandrashekhar Azad ‘Ravan’, a prominent Dalit rights activist, has been held in administrative detention since 3 November 2017. His current term of detention expires in May 2018. However, under the National Security Act, he is at risk of being detained for up to 12 months without charge or trial. Chandrashekhar Azad has been held in administrative detention, without charge or trial, for the past six months. His current term of administrative detention was ordered by a non-judicial Advisory Board that submitted a report to the Uttar Pradesh authorities stating that Chandrashekhar Azad should be detained for six months, with effect from 2 November 2017. On 3 November 2017, Chandrashekhar Azad, the founder of the Dalit rights organisation “Bhim Army”, was arrested and placed under administrative detention under the National Security Act (NSA) on the order of the District Magistrate of Saharanpur. The National Security Act (NSA) permits administrative detention for up to 12 months on loosely defined grounds of national security and maintenance of public order. It is a repressive law that has been used to target human rights defenders in India. Hearings pertaining to Chandrashekhar Azad’s administrative detention are currently underway before the relevant non-judicial Advisory Board. According to his lawyer, the state government remains adamant that Chandrashekhar Azad must be detained for up to six more months after his current term expires in May 2018. The day before he was arrested under the NSA, Chandrashekhar Azad had been granted bail by the Allahabad High Court in relation to his arrest on 8 June 2017. -

Western Uttar Pradesh: Caste Arithmetic Vs Nationalism

VERDICT 2019 Western Uttar Pradesh: Caste Arithmetic vs Nationalism SMITA GUPTA Samajwadi Party patron Mulayam Singh Yadav exchanges greetings with Bahujan Samaj Party supremo Mayawati during their joint election campaign rally in Mainpuri, on April 19, 2019. Photo: PTI In most of the 26 constituencies that went to the polls in the first three phases of the ongoing Lok Sabha elections in western Uttar Pradesh, it was a straight fight between the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) that currently holds all but three of the seats, and the opposition alliance of the Samajwadi Party, the Bahujan Samaj Party and the Rashtriya Lok Dal. The latter represents a formidable social combination of Yadavs, Dalits, Muslims and Jats. The sort of religious polarisation visible during the general elections of 2014 had receded, Smita Gupta, Senior Fellow, The Hindu Centre for Politics and Public Policy, New Delhi, discovered as she travelled through the region earlier this month, and bread and butter issues had surfaced—rural distress, delayed sugarcane dues, the loss of jobs and closure of small businesses following demonetisation, and the faulty implementation of the Goods and Services Tax (GST). The Modi wave had clearly vanished: however, BJP functionaries, while agreeing with this analysis, maintained that their party would have been out of the picture totally had Prime Minister Narendra Modi and his message of nationalism not been there. travelled through the western districts of Uttar Pradesh earlier this month, conversations, whether at district courts, mofussil tea stalls or village I chaupals1, all centred round the coming together of the Samajwadi Party (SP), the Bahujan Samaj Party (BSP) and the Rashtriya Lok Dal (RLD). -

25 May 2018 Hon'ble Chairperson, Shri Justice HL

25 May 2018 Hon’ble Chairperson, Shri Justice H L Dattu National Human Rights Commission, Block –C, GPO Complex, INA New Delhi- 110023 Respected Hon’ble Chairperson, Subject: Continued arbitrary detention and harassment of Dalit rights activist, Chandrashekhar Azad Ravana The Asian Forum for Human Rights and Development (FORUM-ASIA) appeals the National Human Rights Commission (NHRC) to urgently carry out an independent investigation into the continued detention of Dalit human rights defender, Chandrashekhar Azad Ravan, in Saharanpur, Uttar Pradesh State, to furnish the copy of the investigation report before the non-judicial tribunal established under the NSA, and to move the court to secure his release. Chandrashekhar is detained under the National Security Act (NSA) without charge or trial. FORUM-ASIA is informed that in May 2017, Dalit and Thakur communities were embroiled in caste - based riots instigated by the dominant Thakur caste in Saharanpur city of Uttar Pradesh. The riots resulted in one death, several injuries and a number of Dalit homes being burnt. Following the protests, 40 prominent activists and leaders of 'Bhim Army', a Dalit human rights organisation, were arrested but later granted bail. Chandrashekhar Azad Ravan, a young lawyer and co-founder of ‘Bhim Army’, was arrested on 8 June 2017 following a charge sheet filed by a Special Investigation Team (SIT) constituted to investigate the Saharanpur incident. He was framed with multiple charges under the Indian Penal Code 147 (punishment for rioting), 148 (rioting armed with deadly weapon) and 153A among others, for his alleged participation in the riots. Even though Chandrashekhar was not involved in the protests, and wasn't present during the riot, he was detained on 8 June. -

Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada

Responses to Information Requests - Immigration and Refugee Board of... https://irb-cisr.gc.ca/en/country-information/rir/Pages/index.aspx?doc=4... Responses to Information Requests - Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada India: Treatment of Dalits by society and authorities; availability of state protection (2016- January 2020) 1. Overview According to sources, the term Dalit means "'broken'" or "'oppressed'" (Dalit Solidarity n.d.a; MRG n.d.; Navsarjan Trust n.d.a). Sources indicate that this group was formerly referred to as "'untouchables'" (Dalit Solidarity n.d.a; MRG n.d.; Navsarjan Trust n.d.a). They are referred to officially as "Scheduled Castes" (India 13 July 2006, 1; MRG n.d.; Navsarjan Trust n.d.a). The Indian National Commission for Scheduled Castes (NCSC) identified that Scheduled Castes are communities that "were suffering from extreme social, educational and economic backwardness arising out of [the] age-old practice of untouchability" (India 13 July 2006, 1). The Commonwealth Human Rights Initiative (CHRI) [1] indicates that the list of groups officially recognized as Scheduled Castes, which can be modified by the Parliament, varies from one state to another, and can even vary among districts within a state (CHRI 2018, 15). According to the 2011 Census of India [the most recent census (World Population Review [2019])], the Scheduled Castes represent 16.6 percent of the total Indian population, or 201,378,086 persons, of which 76.4 percent are in rural areas (India 2011). The census further indicates that the Scheduled Castes constitute 18.5 percent of the total rural population, and 12.6 percent of the total urban population in India (India 2011). -

'Ambedkar's Constitution': a Radical Phenomenon in Anti-Caste

Article CASTE: A Global Journal on Social Exclusion Vol. 2 No. 1 pp. 109–131 brandeis.edu/j-caste April 2021 ISSN 2639-4928 DOI: 10.26812/caste.v2i1.282 ‘Ambedkar’s Constitution’: A Radical Phenomenon in Anti-Caste Discourse? Anurag Bhaskar1 Abstract During the last few decades, India has witnessed two interesting phenomena. First, the Indian Constitution has started to be known as ‘Ambedkar’s Constitution’ in popular discourse. Second, the Dalits have been celebrating the Constitution. These two phenomena and the connection between them have been understudied in the anti-caste discourse. However, there are two generalised views on these aspects. One view is that Dalits practice a politics of restraint, and therefore show allegiance to the Constitution which was drafted by the Ambedkar-led Drafting Committee. The other view criticises the constitutional culture of Dalits and invokes Ambedkar’s rhetorical quote of burning the Constitution. This article critiques both these approaches and argues that none of these fully explores and reflects the phenomenon of constitutionalism by Dalits as an anti-caste social justice agenda. It studies the potential of the Indian Constitution and responds to the claim of Ambedkar burning the Constitution. I argue that Dalits showing ownership to the Constitution is directly linked to the anti-caste movement. I further argue that the popular appeal of the Constitution has been used by Dalits to revive Ambedkar’s legacy, reclaim their space and dignity in society, and mobilise radically against the backlash of the so-called upper castes. Keywords Ambedkar, Constitution, anti-caste movement, constitutionalism, Dalit Introduction Dr. -

555 Evaluative Report of the Department

Evaluative Report of the Department 1 Name of the Department : Centre for Studies in Rural Management 2 Year of establishment : 1988 3 Is the Department part of a School/Faculty of the : Faculty of Management university? and Technology 4 Names of programmes offered (UG, PG, M.Phil., Ph.D., Integrated Masters; Integrated Ph.D., D.Sc. D.Litt., etc.) : UG : Bachelors of Arts (Rural Development) PG : MBA in Rural Management M. Phil. in Rural Management Ph. D. in Rural Management 5 Interdisciplinary programmes and departments involved : MBA (RM) is an interdisciplinary Management programme where Faculty are from various disciplines and students intake comes from various stream such as Engineering, Science, Social Science, Arts, Commerce, Rural studies etc... 6 Courses in collaboration with other universities, : Arid Community and industries, foreign institutions, etc. Technology, Bhuj 7 Details of programmes discontinued, if any, with reasons : Master of Rural Management (MRM) renamed as MBA (Rural Management) as per UGC notification DONF-1/2014 from 2015 year. 8 Examination System: : Semester Annual/Semester/Trimester/Choice Based Credit System 9 Participation of the department in the courses offered by other departments : Yes Participation of our faculties in UG common stream program and Rural Development program. 555 GVP NAAC-2015 10 Number of teaching posts sanctioned, filled and actual (Professors/Associate Professors/Asst. Professors/others) Sanctioned Filled Actual (Including CAS & MPS) 0 2(CAS) Professor 0 1 - Associate Professor 1 5 4(Direct) Asst. Professor 7 0 0 Others 0 11 Faculty profile with name, qualification, designation, area of specialization, experience and research under guidance No. of Ph.D./ No. -

Today Farm News 27.09.2012 A.M Maize Production in Erode District Is

Today Farm News 27.09.2012 A.M 27.09.2012 Sep Maize production likely to go up Maize production in Erode district is likely to increase this financial year, thanks to the higher prices, good export and domestic demand. The farming community has brought in more than 3,000 hectares under maize crop this year so far and the agriculture officials predict that the total area under the crop will cross 8,500 hectares. In 2011-12, farmers have cultivated maize on 7,346 hectares. “Maize consumption in the country has witnessed a healthy growth following the demand from the poultry sector. A majority of the maize produced in the country is consumed by the poultry farmers. The prices now hover around Rs. 1,400 a quintal and there is good demand in the domestic market. So we expect the acreage under the crop to go up this year,” a senior official in the Agriculture Department says. Apart from the higher price, water shortage is also one of the primary reasons that has forced many farmers to chose less water intensive, short-term crops such as maize. The storage at the Bhavanisagar reservoir, which is the primary water source for more than two lakh acres in the district, is poor due to the scanty rainfall. As a result, the farming community in the district is left with a few crop choices. Many farmers particularly those in the Lower Bhavani Project ayacut are not willing to take up long-term cash crops such as sugarcane, banana and turmeric. They consider short-term crops such as maize for cultivation this year. -

Joint Submission to the United Nations Human Rights Committee, Adoption of List of Issues

JOINT SUBMISSION TO THE UNITED NATIONS HUMAN RIGHTS COMMITTEE, ADOPTION OF LIST OF ISSUES 126TH SESSION, (01 to 26 July 2019) JOINTLY SUBMITTED BY NATIONAL DALIT MOVEMENT FOR JUSTICE-NDMJ (NCDHR) AND INTERNATIONAL DALIT SOLIDARITY NETWORK-IDSN STATE PARTY: INDIA Introduction: National Dalit Movement for Justice (NDMJ)-NCDHR1 & International Dalit Solidarity Network (IDSN) provide the below information to the United Nations (UN) Human Rights Committee (the Committee) ahead of the adoption of the list of issues for the 126th session for the state party - INDIA. This submission sets out some of key concerns about violations of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (the Covenant) vis-à- vis the Constitution of India with regard to one of the most vulnerable communities i.e, Dalit's and Adivasis, officially termed as “Scheduled Castes” and “Scheduled Tribes”2. Prohibition of Traffic in Human Beings and Forced Labour: Article 8(3) ICCPR Multiple studies have found that Dalits in India have a significantly increased risk of ending in modern slavery including in forced and bonded labour and child labour. In Tamil Nadu, the majority of the textile and garment workforce is women and children. Almost 60% of the Sumangali workers3 belong to the so- called ‘Scheduled Castes’. Among them, women workers are about 65% mostly unskilled workers.4 There are 1 National Dalit Movement for Justice-NCDHR having its presence in 22 states of India is committed to the elimination of discrimination based on work and descent (caste) and work towards protection and promotion of human rights of Scheduled Castes (Dalits) and Scheduled Tribes (Adivasis) across India. -

What Is Mayawati's Future In

DAILY SUARGAM | JAMMU EDIT-OPINION MONDAY | JUNE 14, 2021 6 EDITORIAL 100-YEAR JOURNEY~I SANJUKTA DASGUPTA ophy, medieval mysticism, Significantly, the recent clubbed together as joint ven- can education have a holistic ration through the arts have Islamic culture, Zoroastrian emphasis on skill develop- tures primarily discourage objective that recognizes the been rejected in favour of a VDC issue Ahundred years ago, in philosophy, Bengali literature ment, entrepreneurship, critical thinking and freedom multiple intersections of race, pedagogy of force-feeding 1921, Rabindranath Tagore and history, Hindustani liter- start-ups, eliding the need for of configuring ideas and class, colour, caste, creed, reli- for standardized national founded Visva Bharati ature, Vedic and Classical engagement in humanities interfere with creative free- gion, gender and sexuality education.” In a more direct University at Santiniketan, Sanskrit, Pali, Prakrit, and social sciences that dom. So, in unequivocal that can construct a complete awareness campaign regard- It is sad and strange that Village Bolpur, in undivided Bengal. Chinese, Tibetan, Persian, enable breaking free from terms, Nussbaum observes, human being rather than an ing the absolute necessity of Visva Bharati is often regard- Arabic, German, Latin and shibboleths and stereotypes, “Thirsty for national profit, automaton? The Universal literature studies as an essen- Defence Committees (VDC) members ed as the first international Hindi formed its areas of may not have found favour nations and -

Crucial Test of Strength for Kamal Nath Govt. Today

follow us: monday, march 16, 2020 Delhi City Edition thehindu.com 24 pages ț ₹10.00 facebook.com/thehindu twitter.com/the_hindu Farooq Abullah calls Tharoorled panel flags RussianTurkish patrol Axelsen stuns top seed for release of all delay in revamping on Syrian highway cut Tien Chen, clinches All J&K detainees film certification short by protests England title page 12 page 13 page 14 page 20 Printed at . Chennai . Coimbatore . Bengaluru . Hyderabad . Madurai . Noida . Visakhapatnam . Thiruvananthapuram . Kochi . Vijayawada . Mangaluru . Tiruchirapalli . Kolkata . Hubballi . Mohali . Malappuram . Mumbai . Tirupati . lucknow . cuttack . patna NEARBY Confirmed COVID19 cases rise to 114 Modi calls for SAARC emergency fund First case in Uttarakhand; experts call for more testing to check for community transmission Extends $10 mn as India’s contribution SPECIAL CORRESPONDENT sons in Karnataka has now NEW DELHI risen to seven, including the Kallol Bhattacherjee Figures released by the Un victim. NEW DELHI Bhim Army floats party, ion Health Ministry late on A third case of COVID19 The South Asian Association eyes Bihar election Sunday put the number of was confirmed in Telanga for Regional Cooperation GHAZIABAD confirmed cases of COVID19 na of a 48yearold man, (SAARC) should create a The Bhim Army announced in the country at 110. Howev who returned from the fund to fight the threat of the launch of Azad Samaj er, according to reports from Netherlands and was admit COVID19, Prime Minister Party, its political arm, at a glittering ceremony in Noida States, 114 persons have test ted to the Gandhi Hospital Narendra Modi announced on Sunday. -

Collective of Indian Scholars Statement

SUBMISSION TO THE HEARING ON CITIZENSHIP LAWS AND RELIGIOUS FREEDOM Contents INTRODUCTION.......................................................................................................................................................................... 3 CITIZENSHIP IN INDIA .............................................................................................................................................................. 3 ASSAM’S NRC EXERCISE ......................................................................................................................................................... 4 Background ........................................................................................................................................................................... 5 The NRC exercise in Assam (the only state that has undergone one) ............................................................ 5 NRC Modalities in Assam (2013 until Now)................................................................................................................. 6 Foreigners Tribunals: Assam and All India ............................................................................................................... 7 Detention Camps.................................................................................................................................................................. 7 Material Costs ......................................................................................................................................................................