2278-6236 Mughal Revenue Administration in Cuttack

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reg. No Name in Full Residential Address Gender Contact No

Reg. No Name in Full Residential Address Gender Contact No. Email id Remarks 20001 MUDKONDWAR SHRUTIKA HOSPITAL, TAHSIL Male 9420020369 [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 PRASHANT NAMDEORAO OFFICE ROAD, AT/P/TAL- GEORAI, 431127 BEED Maharashtra 20002 RADHIKA BABURAJ FLAT NO.10-E, ABAD MAINE Female 9886745848 / [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 PLAZA OPP.CMFRI, MARINE 8281300696 DRIVE, KOCHI, KERALA 682018 Kerela 20003 KULKARNI VAISHALI HARISH CHANDRA RESEARCH Female 0532 2274022 / [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 MADHUKAR INSTITUTE, CHHATNAG ROAD, 8874709114 JHUSI, ALLAHABAD 211019 ALLAHABAD Uttar Pradesh 20004 BICHU VAISHALI 6, KOLABA HOUSE, BPT OFFICENT Female 022 22182011 / NOT RENEW SHRIRANG QUARTERS, DUMYANE RD., 9819791683 COLABA 400005 MUMBAI Maharashtra 20005 DOSHI DOLLY MAHENDRA 7-A, PUTLIBAI BHAVAN, ZAVER Female 9892399719 [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 ROAD, MULUND (W) 400080 MUMBAI Maharashtra 20006 PRABHU SAYALI GAJANAN F1,CHINTAMANI PLAZA, KUDAL Female 02362 223223 / [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 OPP POLICE STATION,MAIN ROAD 9422434365 KUDAL 416520 SINDHUDURG Maharashtra 20007 RUKADIKAR WAHEEDA 385/B, ALISHAN BUILDING, Female 9890346988 DR.NAUSHAD.INAMDAR@GMA RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 BABASAHEB MHAISAL VES, PANCHIL NAGAR, IL.COM MEHDHE PLOT- 13, MIRAJ 416410 SANGLI Maharashtra 20008 GHORPADE TEJAL A-7 / A-8, SHIVSHAKTI APT., Male 02312650525 / NOT RENEW CHANDRAHAS GIANT HOUSE, SARLAKSHAN 9226377667 PARK KOLHAPUR Maharashtra 20009 JAIN MAMTA -

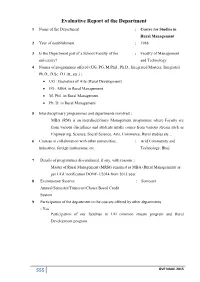

555 Evaluative Report of the Department

Evaluative Report of the Department 1 Name of the Department : Centre for Studies in Rural Management 2 Year of establishment : 1988 3 Is the Department part of a School/Faculty of the : Faculty of Management university? and Technology 4 Names of programmes offered (UG, PG, M.Phil., Ph.D., Integrated Masters; Integrated Ph.D., D.Sc. D.Litt., etc.) : UG : Bachelors of Arts (Rural Development) PG : MBA in Rural Management M. Phil. in Rural Management Ph. D. in Rural Management 5 Interdisciplinary programmes and departments involved : MBA (RM) is an interdisciplinary Management programme where Faculty are from various disciplines and students intake comes from various stream such as Engineering, Science, Social Science, Arts, Commerce, Rural studies etc... 6 Courses in collaboration with other universities, : Arid Community and industries, foreign institutions, etc. Technology, Bhuj 7 Details of programmes discontinued, if any, with reasons : Master of Rural Management (MRM) renamed as MBA (Rural Management) as per UGC notification DONF-1/2014 from 2015 year. 8 Examination System: : Semester Annual/Semester/Trimester/Choice Based Credit System 9 Participation of the department in the courses offered by other departments : Yes Participation of our faculties in UG common stream program and Rural Development program. 555 GVP NAAC-2015 10 Number of teaching posts sanctioned, filled and actual (Professors/Associate Professors/Asst. Professors/others) Sanctioned Filled Actual (Including CAS & MPS) 0 2(CAS) Professor 0 1 - Associate Professor 1 5 4(Direct) Asst. Professor 7 0 0 Others 0 11 Faculty profile with name, qualification, designation, area of specialization, experience and research under guidance No. of Ph.D./ No. -

Today Farm News 27.09.2012 A.M Maize Production in Erode District Is

Today Farm News 27.09.2012 A.M 27.09.2012 Sep Maize production likely to go up Maize production in Erode district is likely to increase this financial year, thanks to the higher prices, good export and domestic demand. The farming community has brought in more than 3,000 hectares under maize crop this year so far and the agriculture officials predict that the total area under the crop will cross 8,500 hectares. In 2011-12, farmers have cultivated maize on 7,346 hectares. “Maize consumption in the country has witnessed a healthy growth following the demand from the poultry sector. A majority of the maize produced in the country is consumed by the poultry farmers. The prices now hover around Rs. 1,400 a quintal and there is good demand in the domestic market. So we expect the acreage under the crop to go up this year,” a senior official in the Agriculture Department says. Apart from the higher price, water shortage is also one of the primary reasons that has forced many farmers to chose less water intensive, short-term crops such as maize. The storage at the Bhavanisagar reservoir, which is the primary water source for more than two lakh acres in the district, is poor due to the scanty rainfall. As a result, the farming community in the district is left with a few crop choices. Many farmers particularly those in the Lower Bhavani Project ayacut are not willing to take up long-term cash crops such as sugarcane, banana and turmeric. They consider short-term crops such as maize for cultivation this year. -

Forest Deptt

AADHAR BASED BIOMETRIC IDENTIFICATION AND SKILL PROFILING Reports Select Department :- FOREST DEPARTMEN Select District :- All Sno. District Name Parentage Address Present Office DOB Category ASSISTANT ALTAF HUSSAIN CONSERVATOR OF SEASONAL 1 ANANTNAG GH MOHD SHAH HALLAN 16-03-1979 SHAH FOREST DEPARTMENT LABOURERS OF SOIL ASSISTANT MANZOOR MOHD SHAFI CONSERVATOR OF SEASONAL 2 ANANTNAG GURIDRAMAN 03-01-1979 AHMAD KHATANA KHATANA FOREST DEPARTMENT LABOURERS OF SOIL ASSISTANT MOHAMMAD ALI MOHD CONSERVATOR OF SEASONAL 3 ANANTNAG HALLAN MANZGAM 01-03-1972 SOOBA CHACHI CHACHI FOREST DEPARTMENT LABOURERS OF SOI ASSISTANT NISAR AHMAD GH NABI NOWPORA WATNARD KOKERNAG CONSERVATOR OF SEASONAL 4 ANANTNAG 01-04-1980 TANTRAY TANTRAY ANG FOREST DEPARTMENT LABOURERS OF SOI ASSISTANT FAROOQ AHMAD GULAM HASSAN CONSERVATOR OF SEASONAL 5 ANANTNAG AIENGATNARD WATNAR 10-04-1975 TANTRY TANTRY FOREST DEPARTMENT LABOURERS OF SOI ASSISTANT http://10.149.2.27/abbisp/AdminReport/District_Wise.aspx[1/16/2018 12:30:14 PM] ABDUL SALAM CONSERVATOR OF SEASONAL 6 ANANTNAG AB REHMAN BHAT KREERI UTTRASOO 02-04-1978 BHAT FOREST DEPARTMENT LABOURERS OF SOIL ASSISTANT GUL HASSAN SHERGUND UTTERSOO SHANGUS CONSERVATOR OF SEASONAL 7 ANANTNAG AB HAMID KHAN 06-11-1980 KHAN ANG FOREST DEPARTMENT LABOURERS OF SOIL ASSISTANT AB REHMAN CONSERVATOR OF SEASONAL 8 ANANTNAG AB QADOOS KHAN DADOO MARHAMA BIJ 02-03-1983 KHAN FOREST DEPARTMENT LABOURERS OF SOIL ASSISTANT MOHD MUSHTAQ CONSERVATOR OF SEASONAL 9 ANANTNAG AB AZIZ GANIE KHANDIPHARI HARNAG 01-02-1981 GANIE FOREST DEPARTMENT LABOURERS -

Investor First Name Investor Middle Name Investor Last Name Father

Investor First Name Investor Middle Name Investor Last Name Father/Husband First Name Father/Husband Middle Name Father/Husband Last Name Address Country State District Pin Code Folio No. DP.ID-CL.ID. Account No. Invest Type Amount Transferred Proposed Date of Transfer to IEPF PAN Number Aadhar Number 74/153 GANDHI NAGAR A ARULMOZHI NA INDIA Tamil Nadu 636102 IN301774-10480786-0000 Amount for unclaimed and unpaid dividend 160.00 15-Sep-2019 ATTUR 1/26, VALLAL SEETHAKATHI SALAI A CHELLAPPA NA KILAKARAI (PO), INDIA Tamil Nadu 623517 12010900-00960311-TE00 Amount for unclaimed and unpaid dividend 60.00 15-Sep-2019 RAMANATHAPURAM KILAKARAI OLD NO E 109 NEW NO D A IRUDAYAM NA 6 DALMIA COLONY INDIA Tamil Nadu 621651 IN301637-40636357-0000 Amount for unclaimed and unpaid dividend 20.00 15-Sep-2019 KALAKUDI VIA LALGUDI OPP ANANDA PRINTERS I A J RAMACHANDRA JAYARAMACHAR STAGE DEVRAJ URS INDIA Karnataka 577201 IN300360-10245686-0000 Amount for unclaimed and unpaid dividend 8.00 15-Sep-2019 ACNPR4902M NAGAR SHIMOGA NEW NO.12 3RD CROSS STREET VADIVEL NAGAR A J VIJAYAKUMAR NA INDIA Tamil Nadu 632001 12010600-01683966-TE00 Amount for unclaimed and unpaid dividend 100.00 15-Sep-2019 SANKARAN PALAYAM VELLORE THIRUMANGALAM A M NIZAR NA OZHUKUPARAKKAL P O INDIA Kerala 691533 12023900-00295421-TE00 Amount for unclaimed and unpaid dividend 20.00 15-Sep-2019 AYUR AYUR FLAT - 503 SAI DATTA A MALLIKARJUNAPPA ANAGABHUSHANAPPA TOWERS RAMNAGAR INDIA Andhra Pradesh 515001 IN302863-10200863-0000 Amount for unclaimed and unpaid dividend 80.00 15-Sep-2019 AGYPA3274E -

Tracing Biometric Assemblages in India's

Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont Scripps Senior Theses Scripps Student Scholarship 2020 Tracing Biometric Assemblages in India’s Surveillance State: Reproducing Colonial Logics, Reifying Caste Purity, and Quelling Dissent Through Aadhaar Priya Prabhakar Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.claremont.edu/scripps_theses Part of the Asian Studies Commons, Civil Rights and Discrimination Commons, Disability Studies Commons, Ethnic Studies Commons, Gender and Sexuality Commons, Human Geography Commons, Models and Methods Commons, Other Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons, Other Film and Media Studies Commons, Politics and Social Change Commons, Race and Ethnicity Commons, Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons, Social Control, Law, Crime, and Deviance Commons, Theory, Knowledge and Science Commons, and the Urban Studies and Planning Commons Recommended Citation Prabhakar, Priya, "Tracing Biometric Assemblages in India’s Surveillance State: Reproducing Colonial Logics, Reifying Caste Purity, and Quelling Dissent Through Aadhaar" (2020). Scripps Senior Theses. 1533. https://scholarship.claremont.edu/scripps_theses/1533 This Open Access Senior Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Scripps Student Scholarship at Scholarship @ Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in Scripps Senior Theses by an authorized administrator of Scholarship @ Claremont. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Tracing Biometric Assemblages in India’s Surveillance State: Reproducing Colonial Logics, Reifying Caste Purity, and Quelling Dissent Through Aadhaar by PRIYA VANKAMAMIDI PRABHAKAR SUBMITTED TO SCRIPPS COLLEGE IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE DEGREE OF BACHELOR OF ARTS PROFESSOR MA PROFESSOR CHATTERJEE MAY 4TH, 2020 2 Acknowledgements: Thank you to all my professors. You have given me skills of critical thinking and helped me recognize my passions. -

The 1907 Anti-Punjabi Hostilities in Washington State: Prelude to the Ghadar Movement Paul Englesberg Walden Universityx

Walden University ScholarWorks The Richard W. Riley College of Education and Colleges and Schools Leadership Publications 2015 The 1907 Anti-Punjabi Hostilities in Washington State: Prelude to the Ghadar Movement Paul Englesberg Walden Universityx Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.waldenu.edu/cel_pubs Part of the Canadian History Commons, Education Commons, and the United States History Commons This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Colleges and Schools at ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Richard W. Riley College of Education and Leadership Publications by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. i Interpreting Ghadar: Echoes of Voices Past Ghadar Centennial Conference Proceedings October 2013 Edited by Satwinder Kaur Bains Published by the Centre for Indo-Canadian Studies University of the Fraser Valley Abbotsford, BC, Canada Centre for Indo Canadian Studies, 2013 University of the Fraser Valley www.ufv.ca/cics ISBN 978-0-9782873-4-4 Bibliothèque et Archives Canada | Library and Archives Canada Partial funding for this publication has been received from The Office of Research, Engagement and Graduate Studies at UFV The Centre for Indo Canadian Studies Ghadar Conference Proceedings 33844 King Road Abbotsford, BC V2S 7M8 Canada Edited by: Satwinder Kaur Bains EPUB Produced by: David Thomson The link to the epub can be found at: www.ufv.ca/cics/research/cics-research-projects/ Cover Design: Suvneet Kaur -

L.M. No. Name and Address for Correspondence 1. Dr

L.M. NAME AND ADDRESS FOR NO. CORRESPONDENCE 1. DR. ASWIN M. THAKER PRINCIPAL COLLEGE OF VETERINARY SCIENCE AND A.H., ANAND AGRICULTURAL UNIVERSITY, ANAND - 388 001 (GUJARAT) 2. DR. SHAILESH KANTILAL BHAVSAR PROFESSOR AND HEAD DEPARTMENT OF PHARMACOLOGY & TOXICOLOGY, COLLEGE OF VETERINARY SCIENCE & A.H., NAVSARI AGRICULTURAL UNIVERSITY, NAVSARI – 396450 (GUJARAT) 3. DR. RAJIT MANI TRIPATHI PROFESSOR AND HEAD (RETIRED) BARPUR P.O. BALWARGANJ, DISTRICT – JAUNPUR, UTTAR PRADESH - 222201 4. DR. SHAILESH KUMAR MODY PROFESSOR & HEAD DEPARTMENT OF PHARMACOLOGY, COLLEGE OF VETERINARY SCIENCE AND A.H., SARDARKRUSHINAGAR DANTIWADA AGRICULTURAL UNIVERSITY, SARDAR KRUSHINAGAR - 385 506 (GUJARAT) 5. DR. VISHNU VITHAL RANADE 203, SAI PRASAD, JAY PRAKASH NAGAR, GOREGAON (E), MUMBAI - 400 063 MAHARASHTRA 6. DR. KAUTUK K SARDAR PROFESSOR DEPTT. OF VETY. PHAMACOLOGY & TOXICOLOGY, ORISSA UNIVERSITY OF AGRICULTURE & TECHNOLOGY BHUBANESWAR - 751 003 (ORISSA) 7. DR. N. PUNNIAMURTHY PROFESSOR & HEAD, VETERINARY UNIVERSITY TRAINING AND RESEARCH CENTRE, NEAR R.T.O. OFFICE, THANJAVUR-TRICHY HIGHWAY, THANJAVUR- 613 403. 8. DR. SATISH KUMAR GARG PRINCIPAL AND DEAN COLLEGE OF VETERINARY SCIENCE & ANIMAL HUSBANDRY, U.P. PANDIT DEEN DAYAL UPADHYAYA PASHU CHIKITSA VIGYAN VISHWA VIDYALA EVAM GO ANUSANDHAN SANSTHAN, MATHURA - 281001 (U.P.) 9. DR. AYUB M.A. SHAH ASSISTANT PROFESSOR (SENIOR GRADE) I/C DEAN, COLLEGE OF VETERINARY SCIENCES & ANIMAL HUSBANDRY CENTRAL AGRICULTURAL UNIVERSITY SELESIH, AIZWAL - 281 001 MIZORAM 10. DR. HARDAN SINGH PANWAR E-8, SHIRIJI GARDEN-2 GOVARDHAN ROAD, MATHURA-281004, U.P. 11. DR. RAJENDRA SINGH A/A 41 CHANDANBAN COLONY, MATHURA-281001, UP (INDIA) 12. DR. N. PRAKASH PROFESSOR AND HEAD DEPT.OF PHARMACOLOGY & TOXICOLOGY, VETERINARY COLLEGE, VINOBANAGAR, SHIVAMOGGA-577 204 (KARNATAKA) 13. -

Catalogue of the Papers of Divyabhanusinh Chavda

OF CONTEMPORARY INDIA Catalogue Of The Papers of Divyabhanusinh Chavda Plot # 2, Rajiv Gandhi Education City, P.O. Rai, Sonepat – 131029, Haryana (India) Dr. Divyabhanusinh Chavda A renowned wildlife expert, nature conservationist, researcher, and author, Dr. Divyabhanusinh Chavda (born in 1941) is, by birth, the scion of the former princely state of Mansa, and was, by profession, the corporate administrator in the Tata Administrative Service. He graduated from Fergusson College, Pune in 1962 with B.A. (Hons.) in Political Science, and secured top rank in M.A. (Political Science) from the University of Poona in 1964. During this period (1958-64), he also worked extensively in the field of archaeology and anthropology with Prof. D.D. Kosambi, studying prehistoric artefacts and nomadic tribes around Pune. He then did his M.Sc. (Econ.) in 1966 from School of Oriental & African Studies, University of London. After the completion of higher education, Divyabhanusinh joined the Tata Administrative Service (of the TATA Group) in 1966and rendered his services in several responsible positions as a member of the Management Committee of Hotel & Restaurant Association of Northern India (1990-2000), Board of Governors of Indian Institute of Tourism and Travel Management, Gwalior (1992-1996), Executive Committee of Federation of Hotel & Restaurant Associations of India (1993-2000), National Council for Hotel Management & Catering Technology (1993- 2001); and Chairman, Tourism Task Force, Federation of Indian Chambers of Commerce and Industry (1994-1996). He served for 34 years with TATA Group and retired as the Chief Operation Officer (COO), Leisure Hotels Division of the Indian Hotels Co. Ltd., The Taj Group of Hotels, Mumbai. -

Med Ieval Ind Ia

KHAN INDIA • HISTORY HISTORICAL HISTORICAL DICTIONARIES OF ANCIENT CIVILIZATIONS AND HISTORICAL ERAS, NO. 20 DICTIONARY OF The medieval period of Indian history is diffi cult to clearly defi ne. It can be considered a long transition from ancient to precolonial times. Its end is marked by Vasco da Gama’s voyage round the Cape of Good Hope in 1498 and the establishment of the Mughal empire (1526). The renewed Islamic advance into north India, from roughly DICTIONARY OF DICTIONARY HISTORICAL 1000 A.D. onward, leading to the rise of the Delhi Sultanate (1206), is the beginning of the medieval period in political and cultural terms. For the purpose of the Historical Dictionary of Medieval India, the period from 1000 AD INDIA MEDIEVAL to 1526 AD is considered India’s medieval times. The turbulent history of this period is told through the book’s chronology, introductory essay, bibliography, and hundreds of cross-referenced dictionary entries on key people, historical geography, the arts, institutions, events, and other important terms. IQTIDAR ALAM KHAN retired as a professor of history from Aligarh Muslim University in Aligarh, India. He was the general president of the Indian History Congress’ 59th session held at Bangalore in 1997. MEDIEVAL INDIA For orders and information please contact the publisher Scarecrow Press, Inc. A wholly owned subsidiary of IQTIDAR ALAM KHAN The Rowman & Littlefi eld Publishing Group, Inc. Cover design by Neil D. Cotterill 4501 Forbes Boulevard, Suite 200 Lanham, Maryland 20706 ISBN-13: 978-0-8108-5503-8 1-800-462-6420 • fax 717-794-3803 ISBN-10: 0-8108-5503-8 90000 www.scarecrowpress.com Cover photo: Dragon-Horse Carvings at Konarak Temple, India 9 780810 855038 © Adam Woolfi tt/CORBIS HDMedIndiaMECH.indd 1 4/7/08 11:45:12 AM 08_013_01_Front.qxd 4/1/08 1:30 PM Page i HISTORICAL DICTIONARIES OF ANCIENT CIVILIZATIONS AND HISTORICAL ERAS Series editor: Jon Woronoff 1. -

Details of Unclaimed Deposits / Inoperative Accounts

CITIBANK We refer to Reserve Bank of India’s circular RBI/2014-15/442 DBR.No.DEA Fund Cell.BC.67/30.01.002/2014-15. As per these guidelines, banks are required to display the list of unclaimed deposits/inoperative accounts which are inactive/ inoperative for ten years or more on their respective websites. This is with a view of enabling the public to search the list of account holders by the name of: Account Holder/Signatory Name Address HASMUKH HARILAL 207 WISDEN ROAD STEVENAGE HERTFORDSHIRE ENGLAND UNITED CHUDASAMA KINGDOM SG15NP RENUKA HASMUKH 207 WISDEN ROAD STEVENAGE HERTFORDSHIRE ENGLAND UNITED CHUDASAMA KINGDOM SG15NP GAUTAM CHAKRAVARTTY 45 PARK LANE WESTPORT CT.06880 USA UNITED STATES 000000 VAIDEHI MAJMUNDAR 1109 CITY LIGHTS DR ALISO VIEJO CA 92656 USA UNITED STATES 92656 PRODUCT CONTROL UNIT CITIBANK P O BOX 548 MANAMA BAHRAIN KRISHNA GUDDETI BAHRAIN CHINNA KONDAPPANAIDU DOOR NO: 3/1240/1, NAGENDRA NAGAR,SETTYGUNTA ROAD, NELLORE, AMBATI ANDHRA PRADESH INDIA INDIA 524002 DOOR NO: 3/1240/1, NAGENDRA NAGAR,SETTYGUNTA ROAD, NELLORE, NARESH AMBATI ANDHRA PRADESH INDIA INDIA 524002 FLAT 1-D,KENWITH GARDENS, NO 5/12,MC'NICHOLS ROAD, SHARANYA PATTABI CHETPET,CHENNAI TAMILNADU INDIA INDIA 600031 FLAT 1-D,KENWITH GARDENS, NO 5/12,MC'NICHOLS ROAD, C D PATTABI . CHETPET,CHENNAI TAMILNADU INDIA INDIA 600031 ALKA JAIN 4303 ST.JACQUES MONTREAL QUEBEC CANADA CANADA H4C 1J7 ARUN K JAIN 4303 ST.JACQUES MONTREAL QUEBEC CANADA CANADA H4C 1J7 IBRAHIM KHAN PATHAN AL KAZMI GROUP P O BOX 403 SAFAT KUWAIT KUWAIT 13005 SAJEDAKHATUN IBRAHIM PATHAN AL KAZMI -

Cummins India

Sr. No.FOLIONO BENENAME Address AMOUNT 1 IN30302860186340 NANDKISHORE SHEKARAN PARAMAL MANDOTHAN P O BOX 169 P C 113 MUSCATOMAN 113 199.00 2 G010253 GIRIRAJ KUMAR DAGA C/O SHREE SWASTIK INDUSTRIES DAGA MOHOLLA BIKANER 0 0 1400.00 3 R027270 RAJNI DHAWAN C-398, DEFENCE COLONY NEW DELHI NEW DELHI 110024 490.00 4 U004751 UMESH CHANDRA CHATRATH C-398, DEFENCE COLONY NEW DELHI NEW DELHI 110024 490.00 5 1204720005680789 MADAN LAL ARORA 21 NISHANT KUNJ NEAR TV TOWER SARASWATI VIHAR DELHI NEW DELHI 110034 840.00 6 1202300000147708 SACHIN KHATRI 236 BLOCK RU PITAMPURA DELHI 110088 63.00 7 IN30134820128789 BADRI PRASAD GUPTA D 18 JHILMIL COLONY EAST DELHIDELHI 110095 826.00 8 0010422 NEENA MITTAL 15/265 PANCH PEER STREET NOORI GATE UTTAR PRADESHAGRA 0 0 14.00 9 IN30096610475355 SADHNA 59/ 4341 REGHAR PURA KAROL BAGHNEW DELHI 110005 56.00 10 IN30021416562959 CHANDER SHEKHER KAPOOR 12/2 12- BLOCK SHAKTI NAGAR DELHI DELHI DELHI 110007 647.00 11 IN30155721251394 ASHISH SEHDEV RL-3, GANGA RAM VATIKA PO-TILAK NAGAR NEW DELHI 110018 35.00 12 1204470006112131 GAURAV DHAMIJA 140 EVER GREEN CGHS PLOT NO 9 SECTOR 7 DWARKA DELHI 110045 35.00 13 IN30159010012885 SHASHI KATYAL C- 1 A/106 c JANAK PURI NEW DELHI 110058 105.00 14 R027024 RAJESH CHANDER MURGAI 106/1B (NEAR MCD SCHOOL) KISHAN GARH NEW DELHI SOUTH WEST DELHI 110070 980.00 15 IN30302855052722 PAULSON KOCHERY PAUL 10TH STREET BLDG 7 DOOR 30 BLOCK 10 SALMIYAHKUWAIT 13014 999999 831.00 16 1202990001556651 S N SINGH ALPHA TECHNICAL SERVICES PVT LTD A 22 BLOCK B 1 MOHAN CO IND AREA NEW DELHI 110044 98.00 17 IN30133017631632 RAJDEV SHARMA L 1 /A LAXMI NAGAR VIJAY CHOWK,DELHI 110092 140.00 18 R025552 ROSHANI DEVI HOUSE NO.806 SECTOR 15A FARIDABADHARYANA FARIDABAD 121007 1470.00 19 IN30177411078173 LALIT KUMAR JAIN HOUSE NO 5 JINDAL SCHOOL MAYADHISSAR 125005 98.00 20 IN30133020668905 SONIA GAUR H NO 1570 SECTOR 26 PANCHKULA 134109 7.00 21 1100001100016244 SPFL SECURITIES LTD 15/63 M CIVIL LINES KANPUR KANPUR 208001 582.00 22 1202980000081696 CYRUS JOSEPH .