The Munich Visiting Program, 1960-1972

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sabrina Hernandez Thesis Adviso

Bavaria: More than Just Oktoberfest Bayern: Mehr als nur Oktoberfest An Honors Thesis (HONR 499) by Sabrina Hernandez Thesis Advisor Dr. Laura Seset Ball State University Muncie, IN November 2017 Expected Date of Graduation December 2017 2 Abstract In this paper I discuss several aspects of Munich and Bavaria. The city is a central hub for the region that has its own unique history, language, and cultural aspects. The history of the city' s founding is quite interesting and also has ties to the history of the German nation. The language spoken in Bavaria is specific to the region and there are several colloquialisms that are only used in Germany's southernmost region. The location of the city is also an important topic discussed in the paper as well. Acknowledgments I would like to thank Dr. Laura Seset for advising me throughout this process. Her help and support throughout the process was more than I could have asked for in a thesis advisor. Her encouragement to go on this trip was something that drew me to these unique experiences that I would not have had, had I not decided to go on this trip. I would also like to thank her for helping me improve my German writing abilities, which was incredibly helpful during my time abroad. Vielen Dank Frau Seset, ohne Ihnen hatte ich dass nicht geschaft! I would also like to thank my parents for encouraging me throughout all four years here at Ball State and for providing me with the opportunity to study abroad. Without their support and encouragement this would have been an impossible task. -

Establishing US Military Government: Law and Order in Southern Bavaria 1945

Portland State University PDXScholar Dissertations and Theses Dissertations and Theses 11-4-1994 Establishing US Military Government: Law and Order in Southern Bavaria 1945 Stephen Frederick Anderson Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/open_access_etds Part of the History Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Anderson, Stephen Frederick, "Establishing US Military Government: Law and Order in Southern Bavaria 1945" (1994). Dissertations and Theses. Paper 4689. https://doi.org/10.15760/etd.6573 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. THESIS APPROVAL The abstract and thesis of Stephen Frederick Anderson for the Master of Arts in History were presented November 4, 1994. and accepted by the thesis committee and the department. COMMITTEE APPROVALS: Franklin C. West, Chair Charles A. Tracy Representative of the Office of Graduate Stuil DEPARTMENT APPROVAL: David A. Jo Department * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * ACCEPTED FOR PORTLAND STATE UNIVERSITY BY THE LIBRARY on c:z;r 4-M;t?u£;.~ /99'1 ABSTRACT An abstract for the thesis of Stephen Frederick Anderson for the Master of Arts in Histoty presented November 4, 1994. Title: Establishing US Militaty Government: Law and Order in Southern Bavaria 1945. In May 1945, United States Militaty Government (MG) detachments arrived in assigned areas of Bavaria to launch the occupation. By the summer of 1945, the US occupiers became the ironical combination of stern victor and watchful master. -

Gemütlichkeit SUBSCRIBER the Travel Letter for Germany, Austria, Switzerland & the New Europe

DEAR GEMüTLICHKEIT SUBSCRIBER The Travel Letter for Germany, Austria, Switzerland & the New Europe Tales of Travel Trouble Gemütlichkeit has never done traditional advertising such as TV MUNICH and radio. For years the same direct Munich is Germany’s most popular destination, also it’s most expensive. This mail piece that describes our servic- month we show you how to make your euros go farther in the Bavarian capital. es has been the main source of sub- scribers. Thus, an advertising slo- unich bills itself as “the Munich attracts more than 4.5 gan is something we’ve never con- city of laptops and Leder- million visitors a year. sidered. Lufthansa’s is “There’s No M hosen”—an appropriate And in a nationwide poll, 75 Better Way to Fly.” Hilton Hotels’ description of Germany’s third- say “Travel Should Take you Plac- percent of Germans said if they largest metropolis, where cutting- could choose to live anywhere in es.” The Nike tagline, “Just Do It,” edge high-tech seems good and I really like John by Sharon Hudgins their own country, it would be in and old Bavarian Munich. Deere’s, “Nothing Runs Like a traditions go together like Bratwurst Castles and churches have long Deere.” Based on reports we get and Bier. from returning travelers maybe been an important architectural ours should be, “Know Before You Founded in 1158, Munich cele- feature of Munich, the seat of Cath- Go.” This summer we’ve heard brates its 850th birthday this year, olic bishops and German royalty for about some bad things that have as well as its 175th Oktoberfest. -

Simply Explore Guided Tours for Groups

simply seasonal The cult of Dult! Meet a true Munich original. A guided tour through the Auer Dult, Munich’s traditional market event – Maidult (last week in April), Jakobidult (last week in July) and Kirchweihdult (mid-October) (Max. 20 people) simply unique A trip to Oktoberfest! Sophisticated technology, tradition and nostalgia meet at Oktoberfest. Discover Guided tours through the Residenz, Schloss Nymphen- interesting facts and hidden secrets about the world’s burg (Nymphenburg Palace) or Schloss Schleissheim largest folk festival! (Max. 15 people) (Schleissheim Palace). Origins and nostalgia – a guided tour through the Artistic Munich. A walking tour through the museum Oide Wiesn festival grounds. The historic Wiesn area, district, covering the museums and their treasures stretching a separate section of the Oktoberfest, brings the history from ancient to modern. of the festival to life. (Max. 20 people) Excursions to the Bavarian Oberland or the palaces Tasty treats, Fatschnkindl and stories at the Christmas of Ludwig II. market on Marienplatz. A culinary tour of the market. (Max. 20 people) City tours and excursions with a taxi guide for smaller groups of up to 7 people. Create your own tour of Munich “Fruitcake and Fatschnkindl” – a cultural and historic with a specially trained taxi guide or enjoy a trip to the royal walking tour through the Christmas market on palaces. Marienplatz square. This special tour focuses on the traditions and history of the Christmas market. simply explore Guided tours for groups You can book these tours through München Tourismus guest tour team We will find the perfect guided tour for any group, be it on foot, by bus or by taxi. -

42EMWA Conference

nd EMWA 42 Conference 4th EMWA Symposium Thursday 12 May 2016 10–14 May 2016 Sheraton Munich Arabellapark Hotel Munich, Germany | 1 | www.emwa.org Contents Message from the President and Conference Director . 3. Quick guide to EMWA conference sessions . 4 EMWA Professional Development Programme . 5 Fees and registration . 7 Conference overview . 9 Conference venue and accommodation . 17 4th EMWA Symposium “Scientific and Medical Communication Today” . 19 Expert Seminar Series . 20 Social events . 23 Speaker profiles . 26 Future events . 29 Gold Corporate Partner Silver Corporate Partner Contact EMWA Head Office Tel: +44 (0)1625 664 534 Email: [email protected] Remember to download the EMWA conference app | 2 | Message from the President and Conference Director Dear Delegates Registration for the EMWA Munich Spring Conference is now open and your Executive Committee and an army of volunteers have been working hard to put together another stimulating programme . Our spring conference content has flourished from a sound offering of workshops with a Symposium in May 2014 into the multi-layered programme that we now offer . 35 foundation and 16 advanced workshops, the Freelance Business Forum and the buzz of medical writers networking will underpin the conference . The 4th Symposium Day on ‘Scientific and Medical Communication Today’ will bring us together with cross-industry speakers, panellists and regulators for lively debate on our ever-changing professional landscape . Experienced members will enjoy the 2nd Expert Seminar Series, covering topics as diverse as clinical trial disclosure; referencing software; running medical writing groups in India, China and Japan; artificial intelligence; and adaptive study design . Special Interest Groups (SIGs) will provide EMWA’s very own ‘talking shops’ on hot topics that are expected to develop and endure . -

Museums and Collections Master Thesis

Leiden University Master Arts & Culture Specialization: Museums and Collections Master Thesis Memory is the Foundation of the Future: Holocaust Museums Memory Construction through Architecture and Narrative, Yad Vashem and the Jewish Museum in Berlin. By Lucrezia Levi Morenos Student Number: 2231719 2018-2019 Supervised by Dr. Mirjam Hoijtink Word Count: 17725 Table of Contents Acknowledgments III Introduction 1 Chapter I Yad Vashem 8 I.1 Geographic Significance and Architecture 9 I.2 The Holocaust History Museum’s Narrative 13 Chapter II The Jewish Museum in Berlin 21 II.1 Geographic Significance and Architecture 22 II.2 Narrative of the Jewish Museum in Berlin 27 II.3 Old Permanent Collection Design and ‘Welcome to Jerusalem’ 33 Chapter III Comparing Yad Vashem and the Jewish Museum in Berlin and Exploring Current Events Surrounding the Two Institutions III.1 Yad Vashem and the Jewish Museum in Berlin 38 III.2 Current Debates 41 Conclusion 47 List of Illustrations 50 Bibliography 58 II Acknowledgements Writing this thesis has been a gratifying experience and there are some people I would like to thank for helping me shape this project. First, I would like to thank my supervisor, Mirjam Hoijtink for always being available to help me and giving me suggestions on how to improve my work. In particular, I would like to thank her for introducing me to the field of memory studies; thanks to her advice I developed a work much more critical and I discovered a new field of studies that fascinates me. The topic of Holocaust museums is very complex and this thesis gave me the opportunity to explore questions that have been in my mind for a long time. -

2011 Annual Report and Is Organizing the 2012 Silent Spring Essay Contest

Themenbereich, Kapitel 1 One of the highlights, if not the highlight, of the “Year of Energy” is the exhibition “Dis- coveries 2010: Energy,” which is on display on Mainau Island on Lake Constance from May 20 to August 29, 2010. Known as the “Flower Island,” Mainau is not only popular with tourists and a favorite spot for day trips, but is also known as a historic site for the environmental movement. In 1961 Count Lennart Bernadotte, the owner of the island, formulated the “Mainau Green Charter” as a public manifesto for nature protection and environmental resource management, anticipating what has later been termed sustai- nability. Since then, Mainau has been developed by the Bernadotte family as a kind of ecological paradise, showcasing the beauty of nature. In 2009, the Bernadotte family, in collaboration with “The Nobel Laureate Meetings at Lindau,” was able to present a small exhibition on the overarching theme of water. This exhibition was primarily financed by the Federal Ministry of The Center aims to foster local, national, and international dialogue and analysis of the interaction between human agents and nature; it aims to in- crease the visibility of the humanities in the current discussions about the environment; and it will help establish environmental studies as a distinct field of research and provide it with an institutional home. While the Center’s home is in Munich, Germany, one of Theits main goals Rachel is the internationalization Carson of environmental Centerstudies. It brings together international academics working on the complex relationship of nature and culture ac- forross various Environment disciplines. -

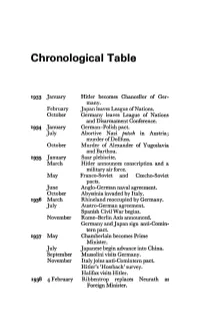

Chronological Table

Chronological Table 1933 January Hitler becomes Chancellor of Ger many. February Japan leaves League ofNations. October Germany leaves League of Nations and Disarmament Conference. 1934 January German-Polish pact. July Abortive Nazi putsch in Austria; murder ofDollfuss. October Murder of Alexander of Yugoslavia and Barthou. 1935 January Saar plebiscite. March Hitler announces conscription and a military air force. May Franco-Soviet and Czecho-Soviet pacts. June Anglo-German naval agreement. October Abyssinia invaded by Italy. 1936 March Rhineland reoccupied by Germany. July Austro-German agreement. Spanish Civil War begins. November Rome-Berlin Axis announced. Germany and Japan sign anti-Comin- ternpact. 1937 May Chamberlain becomes Prime Minister. July Japanese begin advance into China. September Mussolini visits Germany. November Italy joins anti-Comintern pact. Hitler's 'Hossbach' survey. Halifax visits Hitler. 1938 4 February Ribbentrop replaces Neurath as Foreign Minister. 206 CHRONOLOGICAL TABLE 12 February Schuschnigg visits Hitler at Berchtes- gaden. 20February Resignation of Eden. gMarch Austrian plebiscite announced. II March Schuschnigg forced by Berlin to re- sign. I2 March German occupation ofAustria. 13March Annexation of Austria proclaimed. 28March Konrad Henlein's destructive Sudeten tactics approved by Hitler. r6April Anglo-Italian agreement negotiated. 28-2gApril Daladier and Bonnet in London. 3-gMay Hitler in Italy. 20-22May Scare over Czechoslovakia. 23 July Lord Runciman 'invited' to Czecho slovakia. 7 September The Times follows the lead of the New Statesman in suggesting the cession of the 'Sudetenland'. Benes offers to meet the Sudeten German demands. 8 September Talks between Prague and the Sudeten German Party broken off by latter. 13 September Rioting in Sudetenland. -

Representation of the Holocaust at the Jewish Museum Munich

W&M ScholarWorks Undergraduate Honors Theses Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 5-2008 Simultaneous Presence and Absence: Representation of the Holocaust at the Jewish Museum Munich Emily Geizhals College of William and Mary Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses Recommended Citation Geizhals, Emily, "Simultaneous Presence and Absence: Representation of the Holocaust at the Jewish Museum Munich" (2008). Undergraduate Honors Theses. Paper 815. https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses/815 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Simultaneous Presence and Absence: Representation of the Holocaust at the Jewish Museum Munich A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Bachelors of Arts in Interdisciplinary Studies from The College of William and Mary by Emily Mea Geizhals Accepted for ___________________________________ (Honors, High Honors, Highest Honors) ________________________________________ Philip J. Brendese, Director ________________________________________ Robert S. Leventhal ________________________________________ Leisa D. Meyer ________________________________________ Ryan J. Carey Williamsburg, VA April 21, 20 Introduction1 The three buildings at St.-Jakobs-Platz: (L-R) the Ohel Jakob Synagogue, the Jewish Museum Munich, and the Jewish Community Center. Photo taken by the author. The Jewish Museum Munich’s three-story sandstone building is a commanding presence against the backdrop of the traditional architecture of central Munich. Museum visitors and other passers-by pause at all sides of the building to read quotes from Sharone Lifschitz’s project “Speaking Germany” displayed on the glass exterior of the first floor of the Museum.2 The open doors and exposed first level make the entrance to the Museum inviting. -

English Courses Winter 2019-20

INTERNATIONALE ANGELEGENHEITEN INTERNATIONAL OFFICE COURSES TAUGHT IN ENGLISH Winter Semester 2019/20 1 Referat Internationale Angelegenheiten Ludwigstraße 27, G007 80539 München [email protected] [email protected] www.lmu.de/en/international/incoming LUDWIG-MAXIMILIANS-UNIVERSITÄT MÜNCHEN 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of Contents .................................................................................................................................................................. 2 General Introduction ............................................................................................................................................................ 3 Catholic Theology ................................................................................................................................................................. 5 Protestant Theology ............................................................................................................................................................. 5 Law ........................................................................................................................................................................................ 5 Business Administration ....................................................................................................................................................... 6 Economics .......................................................................................................................................................................... -

Sample Itinerary Location: Munich, Germany (For the Oktoberfest

Sample Itinerary Location: Munich, Germany (for the Oktoberfest celebration) Prepared by “Local Cousin” Isabella 1 Trip Background: Anna is visiting Munich, Germany during Oktoberfest this year with her husband Chris from New York. It is their first time to Germany and they want insider tips from a local on how to navigate the largest beer festival in the world and ensure they get the real “local experience”. Since they are spending five days in Munich they also want to see the heart and soul of the city from a local’s point of view and take in a few popular sites. Lastly, they want to eat where the locals do and want to visit some hole-in-the-wall eateries (and maybe sneak in one nice meal!). They don’t have any dietary restrictions and want to stick with German cuisine for most of the trip (Chris also has a sweet tooth!). General Information: Oktoberfest is the largest beer festival in the world. It is held annually over 16 days and this year it is being held from September 17th – October 3rd, 2016 in Munch, Germany. This is peak tourist season full of locals, families and people in search of a good beer! Here are some helpful tips for you to get around: When you visit Oktoberfest, use public transportation and Uber is another popular option. The infrastructure in Munich is excellent and the U-Bhan (electric rail system) can bring you right to where the action is. If you drive, it’s difficult to find a parking lot. Oktoberfest is full of rollercoasters, fun houses and beer tents. -

Hitler's 'Mein Kampf' Becomes German Bestseller: Publisher 3 January 2017

Hitler's 'Mein Kampf' becomes German bestseller: publisher 3 January 2017 The first reprint of Adolf Hitler's "Mein Kampf" in are gaining ground." Germany since World War II has proved a surprise bestseller, heading for its sixth print run, its 'Not reactionaries or radicals' publisher said Tuesday. The institute said the data collected about buyers The Institute of Contemporary History of Munich by regional bookstores showed that they tended to (IfZ) said around 85,000 copies of the new be "customers interested in politics and history as annotated version of the Nazi leader's anti-Semitic well as educators" and not "reactionaries or manifesto had flown off the shelves since its rightwing radicals". release last January. Nevertheless, the IfZ said it would maintain a However the respected institute said that far from restrictive policy on international rights. For now, promoting far-right ideology, the publication had only English and French editions are planned enriched a debate on the renewed rise of despite strong interest from many countries. "authoritarian political views" in contemporary Western society. The institute released the annotated version of "Mein Kampf" last January, just days after the It had initially planned to print only 4,000 copies copyright of the manifesto expired. but boosted production immediately based on intense demand. The sixth print run will hit Bavaria was handed the rights to the book in 1945 bookstores in late January. when the Allies gave it control of the main Nazi publishing house following Hitler's defeat. The two-volume work had figured on the non- fiction bestseller list in weekly magazine Der For 70 years, it refused to allow the inflammatory Spiegel over much of the last year, and even tract to be republished out of respect for victims of topped the list for two weeks in April.