Dreaming India/India Dreaming

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

700 032 September 7, 2021 a D M I S S I O N B.A

JADAVPUR UNIVERSITY KOLKATA – 700 032 September 7, 2021 A D M I S S I O N B.A. (HONOURS) COURSE IN POLITICAL SCIENCE SESSION 2021 - 2022 The Lists are provisional and are subject to: i. fulfilling the eligibility criteria as notified earlier. ii. verification of the equivalence of marks/degrees from other Boards/Councils to those of the West Bengal council of Higher Secondary Education /Other equivalent Board/Council, wherever applicable. iii. correction in the merit position due to error, if any. All admissions are provisional. As per the order of Govt. of West Bengal [order no: 706-Edn(CS)/10M-95/14 dated 13/7/2021], all the original documenmts of applicants will be verified when they report for classes at University campus. Provisional admission of a candidate will stand cancelled if the documents are found not in conformity with the declaration in the forms submitted on-line. If at the time of document verification, it is found by the university authority that a student does not satisfy the eligibility criteria, s/he will not be considered for admission, even if he/she is provisionally selected for admission. a student does not have completed result at +2 level, his/her application shall be cancelled even if he/she is provisionally selected for admission. a candidate has already graduated from a college with a Bachelors degree, her/his application shall be cancelled even if he/she is provisionally selected for admission, since s/he cannot enrol herself/himself for another Bachelors degree course. Those candidates who have -

Subhash Chandra Bose and His Discourses: a Critical Reading”, Thesis Phd, Saurashtra University

Saurashtra University Re – Accredited Grade ‘B’ by NAAC (CGPA 2.93) Thanky, Peena, 2005, “Subhash Chandra Bose and his discourses: A Critical Reading”, thesis PhD, Saurashtra University http://etheses.saurashtrauniversity.edu/id/827 Copyright and moral rights for this thesis are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. Saurashtra University Theses Service http://etheses.saurashtrauniversity.edu [email protected] © The Author SUBHASH CHANDRA BOSE AND HIS DISCOURSES: A CRITICAL READING A THESIS SUBMITTED TO SAURASHTRA UNIVERSITY, RAJKOT FOR THE DEGREE OF Doctor of Philosophy IN ENGLISH Supervised by: Submitted by: Dr. Kamal Mehta Mrs. Peena Thanky Professor, Sainik School, Smt. H. S. Gardi Institute of Balachadi. English & Comparative (Dist. Jamnagar) Literary Studies, Saurashtra University, Rajkot. 2005 1 SUBHAS CHANDRA BOSE 1897 - 1945 2 SMT. H. S. GARDI INSTITUTE OF ENGLISH & COMPARATIVE LITERARY STUDIES SAURASHTRA UNIVERSITY RAJKOT (GUJARAT) CERTIFICATE This is to certify that the work embodied in this thesis entitled "Subhash Chandra Bose and His Discourses : A Critical Reading" has been carried out by the candidate Mrs. Peena Thanky under my direct guidance and supervision for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy, in the Faculty of Arts of Saurashtra University, Rajkot. -

Rainfall, North 24-Parganas

DISTRICT DISASTER MANAGEMENT PLAN 2016 - 17 NORTHNORTH 2424 PARGANASPARGANAS,, BARASATBARASAT MAP OF NORTH 24 PARGANAS DISTRICT DISASTER VULNERABILITY MAPS PUBLISHED BY GOVERNMENT OF INDIA SHOWING VULNERABILITY OF NORTH 24 PGS. DISTRICT TO NATURAL DISASTERS CONTENTS Sl. No. Subject Page No. 1. Foreword 2. Introduction & Objectives 3. District Profile 4. Disaster History of the District 5. Disaster vulnerability of the District 6. Why Disaster Management Plan 7. Control Room 8. Early Warnings 9. Rainfall 10. Communication Plan 11. Communication Plan at G.P. Level 12. Awareness 13. Mock Drill 14. Relief Godown 15. Flood Shelter 16. List of Flood Shelter 17. Cyclone Shelter (MPCS) 18. List of Helipad 19. List of Divers 20. List of Ambulance 21. List of Mechanized Boat 22. List of Saw Mill 23. Disaster Event-2015 24. Disaster Management Plan-Health Dept. 25. Disaster Management Plan-Food & Supply 26. Disaster Management Plan-ARD 27. Disaster Management Plan-Agriculture 28. Disaster Management Plan-Horticulture 29. Disaster Management Plan-PHE 30. Disaster Management Plan-Fisheries 31. Disaster Management Plan-Forest 32. Disaster Management Plan-W.B.S.E.D.C.L 33. Disaster Management Plan-Bidyadhari Drainage 34. Disaster Management Plan-Basirhat Irrigation FOREWORD The district, North 24-parganas, has been divided geographically into three parts, e.g. (a) vast reverine belt in the Southern part of Basirhat Sub-Divn. (Sundarban area), (b) the industrial belt of Barrackpore Sub-Division and (c) vast cultivating plain land in the Bongaon Sub-division and adjoining part of Barrackpore, Barasat & Northern part of Basirhat Sub-Divisions The drainage capabilities of the canals, rivers etc. -

August 15, 1947 the Saddest Day in Pondicherry

August 15, 1947 The saddest day in Pondicherry Claude Arpi April 2012 Background: India becomes Independent On August 15, 1947 a momentous change occurred on the sub-continent: India became independent, though divided. Nehru, as the first Prime Minister uttered some words which have gone down in history: Long years ago we made a tryst with destiny, and now the time comes when we shall redeem our pledge, not wholly or in full measure, but very substantially. At the stroke of the midnight hour, when the world sleeps, India will awake to life and freedom. A moment comes, which comes but rarely in history, when we step out from the old to the new, when an age ends, and when the soul of a nation, long suppressed, finds utterance. It is fitting that at this solemn moment we take the pledge of dedication to the service of India and her people and to the still larger cause of humanity. A few years ago, I studied the correspondence between the British Consul General in Pondicherry, Col. E.W Fletcher1 and the Indian Ministry of External Affairs and Commonwealth during these very special times. Fletcher who was the Indian Government’s informant in Pondicherry, still a French Colony, wrote to Delhi that the stroke of midnight did not change much in Pondicherry. Though technically the British Colonel was not supposed to have direct relations with the Government of India anymore, he continued to write to the Indian officials in Delhi. His correspondence was not even renumbered. His Secret Letter dated August 17, 1947 bears the reference D.O. -

Chief Engineer (HQ.), Public Works Directorate Government of West

Chief Engineer (HQ.), Io NABANNA.8th Floor. Public Works Directorate 325, Sarat Chatterjee Road, Shibpur, Government of West Bengal Howrah -711102 Tel No: 033-2214-3619, Fax No: 033-2214-3343 emailld:[email protected] No. 1227/CE(HQ)/PWD Date: 02.09.2020 ORDER The following noted Junior Engineers (Civil) under the P.W.D.• as tabulated below are hereby transferred from their present place of posting and on such transfer they are posted at the office as indicated against their names. with immediate effect and until further order. T.AID.A. is admissible as per rule. SI. Name Present Place of Posting. Posting on Tranfer. No. Estimator under the office of the Barrackpore Sub-Division- II, under I Shri Sanjoy Basu. Superintendent, Governor's Esate, Barrackpore Division, P.W.Dte. W.B. Kolkata Raj Bhavan Sub-Division Barrackpore Sub-Division- II, Shri Tarun Kumar 2 under Superintendent, Governor's under Barrackpore Division, Sharma Sarkar. Esate, W.B. P.W.Dte. Bidhannagar West Sub-Division-1Il Shri Ashim Estimator,Birbhum Division, 3 under Bidhannagar West Sub- Bhowmik. P.W.Dte. Division. P.W.Dte. Durgapur Sub Division under Shri Basudev Western Circle, Social Sector, 4 Asansol Division, Social Chandra. P.W.Dte. Sector,P. W.Dte. Bidhannagar West Sub-Division-1Il Shri Manab Estimator, Asansol Division, Social 5 under Bidhannagar West Sub- Mondal. Sector, P.W.Dte. Division. P.W.Dte. Shri Swapan Kumar Estimator, Murshidabad Division, Office of the Chief Engineer, 6 Bera. Social Sector, P.W.Dte. Planning, P.W.Dte. Shri Dilip Office of the Chief Engineer, Estimator, Murshidabad Division, 7 Karmakar. -

Download the File As PDF Format

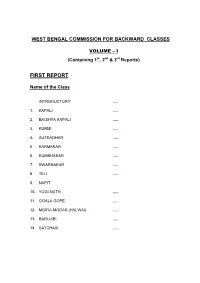

WEST BENGAL COMMISSION FOR BACKWARD CLASSES VOLUME – I (Containing 1 st , 2 nd & 3 rd Reports) FIRST REPORT : Name of the Class INTRODUCTORY ….. 1. KAPALI ….. 2. BAISHYA KAPALI ….. 3. KURMI ….. 4. SUTRADHAR ….. 5. KARMAKAR ….. 6. KUMBHAKAR ….. 7. SWARNAKAR ….. 8. TELI ….. 9. NAPIT 10. YOGI-NATH ….. 11. GOALA GOPE ….. 12. MOIRA-MODAK (HALWAI) ….. 13. BARUJIBI ….. 14. SATCHASI ….. SECOND REPORT : Name of the Class INTRODUCTORY ….. 1. MALAKAR ….. 2. TANTI ….. 3. KANSARI ….. 4. SHANKHAKAR ….. 5. KOERI / KOIRI ….. 6. RAJU ….. 7. TAMBOLI / TAMALI ….. 8. NAGAR ….. 9. KARANI ….. 10. DHANUK ….. 11. SARAK ….. 12. JOLAH (ANSARI-MOMIN) ….. THIRD REPORT : INTRODUCTORY ….. 1. RONIWAR ….. 2. KOSTA / KOSTHA ….. 3. CHRISTIANS CONVERTED FROM SCHEDULED CASTES ….. WEST BENGAL COMMISSION FOR BACKWARD CLASSES REPORT – I Representations have reached the West Bengal Commission for Backward Classes from various classes of citizens for inclusion in the lists of Backward Classes of the State. The West Bengal Commission for Backward Classes other than Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes has been set up by the Act of the State Legislature – “West Bengal Commission for Backward Classes Act, 1993 (West Bengal Act I of 1993)”. The Act provides “it is expedient to constitute a State Commission for Backward Classes other than the Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes and to provide matters connected therewith or incidental thereto”; and accordingly, the Act called “The West Bengal Commission for Backward Classes Act” (hereinafter referred to as the Act) came to be enacted. In terms of the provisions contained in Section 3 of the Act the State Government has constituted this body to be known as “The West Bengal Commission for Backward Classes“ (which will hereinafter be referred to as the Commission) to exercise the powers conferred on and to perform the functions assigned to the commission under the Act. -

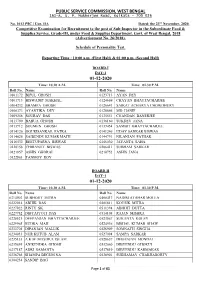

Schedule of Personality Test to the Post of Sub-Inspector in The

PUBLIC SERVICE COMMISSION, WEST BENGAL 161-A, S. P. Mukherjee Road, Kolkata – 700 026 No. 1013 PSC / Con. IIA Dated: the 23rd November, 2020. Competitive Examination for Recruitment to the post of Sub-Inspector in the Subordinate Food & Supplies Service, Grade-III, under Food & Supplies Department, Govt. of West Bengal, 2018 (Advertisement No. 26/2018). Schedule of Personality Test. Reporting Time : 10:00 a.m. (First Half) & 01:00 p.m. (Second Half) BOARD-I DAY-1 01-12-2020 Time: 10.30 A.M. Time: 01.30 P.M. Roll No. Name Roll No. Name 0101172 BIPUL GHOSH 0123713 AYAN DEY 0101713 BISWADIP MAKHAL 0124669 CHAYAN BHATTACHARJEE 0104232 SHAMPA GHOSH 0126641 SAIKAT ACHARYA CHOWDHURY 0106373 AYANTIKA DEY 0126666 MD HANIF 0109256 SOURAV DAS 0135551 CHANDAN BANERJEE 0113799 BABUA GHOSH 0136160 SUKDEV JANA 0113912 SOUMEN GHOSH 0137454 SAMBIT BHATTACHARJEE 0114126 GOURISANKAR PATRA 0141246 UDAY SANKAR BISWAS 0114626 SAIBENDU KUMAR MAITI 0144791 NILANJAN PATHAK 0116532 REETUPARNA BISWAS 0146030 JAYANTA SAHA 0120158 CHIRANJIT BISWAS 0206411 SUBHAM SARKAR 0121857 ASHIS GHORAI 0210752 ASHIS JANA 0122861 TANMOY ROY BOARD-II DAY-1 01-12-2020 Time: 10.30 A.M. Time: 01.30 P.M. Roll No. Name Roll No. Name 0214902 SUBHOJIT MITRA 0408417 NADIM ATAHAR MOLLA 0222014 ABHIK DAS 0501811 KOUSIK MITRA 0227022 RINTU SK 0511394 ABHIJIT DUTTA 0227782 DIBYAJYOTI DAS 0514108 RAJAN MISHRA 0228521 DEEPANJAN BHATTACHARJEE 0523567 SUKANTA KOLEY 0229965 RUDRA MAJI 0524936 BISHAL KUMAR SHAW 0233705 DIPANJAN MALLIK 0526909 SOMNATH SINGHA 0234033 NUR KUTUB ALAM 0527094 SAMPA SARKAR 0235133 A K M MASIDUL ISLAM 0528637 DEBANJAN MONDAL 0235691 ANIRENDRA GHOSH 0532060 DIBYENDU GHORUI 0237187 ADRI SAMANTA 0537619 DIBYENDU KARMAKAR 0238766 SHAMPA BEGUM NA 0538901 SUBHAMAY CHAKRABORTY 0304234 SANDIP BAG Page 1 of 61 PUBLIC SERVICE COMMISSION, WEST BENGAL 161-A, S. -

Minutes of the Meeting of the Expert Committee Held on 14Th, 15Th,17Th and 18Th October, 2013 Under the Performing Arts Grants Scheme (PAGS)

No.F.10-01/2012-P.Arts (Pt.) Ministry of Culture P. Arts Section Minutes of the Meeting of the Expert Committee held on 14th, 15th,17th and 18th October, 2013 under the Performing Arts Grants Scheme (PAGS). The Expert Committee for the Performing Arts Grants Scheme (PAGS) met on 14th, 15th ,17thand 18th October, 2013 to consider renewal of salary grants to existing grantees and decide on the fresh applications received for salary and production grants under the Scheme, including review of certain past cases, as recommended in the earlier meeting. The meeting was chaired by Smt. Arvind Manjit Singh, Joint Secretary (Culture). A list of Expert members present in the meeting is annexed. 2. On the opening day of the meeting ie. 14th October, inaugurating the meeting, Sh. Sanjeev Mittal, Joint Secretary, introduced himself to the members of Expert Committee and while welcoming the members of the committee informed that the Ministry was putting its best efforts to promote, develop and protect culture of the country. As regards the Performing Arts Grants Scheme(earlier known as the Scheme of Financial Assistance to Professional Groups and Individuals Engaged for Specified Performing Arts Projects; Salary & Production Grants), it was apprised that despite severe financial constraints invoked by the Deptt. Of Expenditure the Ministry had ensured a provision of Rs.48 crores for the Repertory/Production Grants during the current financial year which was in fact higher than the last year’s budgetary provision. 3. Smt. Meena Balimane Sharma, Director, in her capacity as the Member-Secretary of the Expert Committee, thereafter, briefed the members about the salient features of various provisions of the relevant Scheme under which the proposals in question were required to be examined by them before giving their recommendations. -

Caste and Mate Selection in Modern India Online Appendix

Marry for What? Caste and Mate Selection in Modern India Online Appendix By Abhijit Banerjee, Esther Duflo, Maitreesh Ghatak and Jeanne Lafortune A. Theoretical Appendix A1. Adding unobserved characteristics This section proves that if exploration is not too costly, what individuals choose to be the set of options they explore reflects their true ordering over observables, even in the presence of an unobservable characteristic they may also care about. Formally, we assume that in addition to the two characteristics already in our model, x and y; there is another (payoff-relevant) characteristic z (such as demand for dowry) not observed by the respondent that may be correlated with x. Is it a problem for our empirical analysis that the decision-maker can make inferences about z from their observation of x? The short answer, which this section briefly explains, is no, as long as the cost of exploration (upon which z is revealed) is low enough. Suppose z 2 fH; Lg with H > L (say, the man is attractive or not). Let us modify the payoff of a woman of caste j and type y who is matched with a man of caste i and type (x; z) to uW (i; j; x; y) = A(j; i)f(x; y)z. Let the conditional probability of z upon observing x, is denoted by p(zjx): Given z is binary, p(Hjx)+ p(Ljx) = 1: In that case, the expected payoff of this woman is: A(j; i)f(x; y)p(Hjx)H + A(j; i)f(x; y)p(Ljx)L: Suppose the choice is between two men of caste i whose characteristics are x0 and x00 with x00 > x0. -

Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru Views on Democratic Socialism

International Journal of Humanities and Social Science Research International Journal of Humanities and Social Science Research ISSN: 2455-2070 Impact Factor: RJIF 5.22 www.socialsciencejournal.in Volume 4; Issue 2; March 2018; Page No. 104-106 Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru views on democratic socialism Dr. Ashok Uttam Chothe HOD, Department of Political Science, New Arts, Commerce & Science College, Ahmednagaar, Maharashtra, India Abstract As a thinker he was passionately devoted to democracy and individual liberty this made it inconceivable for him to turn a comrade. He had confidence in man and love for enterprise Dynamism and dynamic were his most loved words. This loaned to his communism a dynamic character. He trusted that communism is more logical and valuable in the financial scene. It depends on logical strategies for endeavoring to comprehend the history, the past occasions and the laws of the improvement. He pursued it, since it can persuade us the reasons of neediness, worldwide clash and government. He understood that Laissez Faire was dead and the group must be composed to build up social and financial justice. Numerous variables contributed for the development of Democratic Socialism in the brain of Nehru. In England he was dubiously pulled in to the Fabians and Socialistic Ideas. When he took an interest in national development these thoughts again blended the coals of Socialistic Ideas in his mind this enthusiasm for communism principally got from books not from the immediate contacts with the wretchedness and misuse of poor by the rich. When he straightforwardly comes into contact with neediness of workers he felt that unimportant political opportunity was inadequate and without social flexibility individuals could gain no ground without social opportunity. -

Rhetorical Analysis on Expectations and Functions in Jawaharlal Nehru’S Eulogy for Mahatma Gandhi

Advances in Language and Literary Studies ISSN: 2203-4714 www.alls.aiac.org.au Rhetorical Analysis on Expectations and Functions in Jawaharlal Nehru’s Eulogy for Mahatma Gandhi Kangsheng Lai* Pingxiang University, China Corresponding Author: Kangsheng Lai, E-mail: [email protected] ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Article history The paper introduces the life story of Mahatma Gandhi and Jawaharlal Nehru and then analyzes Received: October 04, 2018 the relationship between the two great people in India. After Gandhi’s death, Jawaharlal Nehru Accepted: December 12, 2018 delivered the eulogy for commemorating his intimate comrade and respectful mentor Mahatma Published: February 28, 2019 Gandhi, the Father of India. Under generic constraints based on audience’s expectation and need, Volume: 10 Issue: 1 the eulogy is analyzed from the perspectives of two major expectations and five basic functions. Advance access: January 2019 Through the rhetorical analysis of Jawaharlal Nehru’s eulogy, it can be concluded that a good eulogy should meet audiences’ two major expectations and five basic functions. Conflicts of interest: None Funding: None Key words: Eulogy, Mahatma Gandhi, Jawaharlal Nehru, Expectation, Function INTRODUCTION Muslim-majority Pakistan. Religious violence took place in the Punjab and Bengal because of the substitution of Hindus, Life Story of Mahatma Gandhi Muslims, and Sikhs decided on setting up their own land. Mahatma Gandhi was born on October 2, 1869. He was Gandhi paid a visit to the places where religious violence an activist in India who struggled for the independence from broke out, intending to give the affected people solacement the British rule all his life. -

Issn: 2278-6236 a Philosophical Review on Contemporary

International Journal of Advanced Research in ISSN: 2278-6236 Management and Social Sciences Impact Factor: 4.400 A PHILOSOPHICAL REVIEW ON CONTEMPORARY EDUCATION K.G. Nandha Kumar* Abstract: This paper discusses the contemporary educational thoughts. Various Modern educational thinkers, thoughts, methodologies and concepts are analyzed under the light of current educational system. There are different schools of thought which focus on different concepts of education and those are critically studied in philosophical perspective. In India, during and after the freedom struggle there were varieties of education systems. Education was viewed as a way to attaining goals in the life but now it is a way to get a job in competitive world. Definition of success is variable and it is changed every decade. Philosophical concepts are base for any type of education. The scenario is changed every time based on day to day requirement in the life. Monetary needs are high at present. The role of education in an individual to the nation is studied under different thoughts. Keywords: Education, philosophers, thoughts, knowledge, problems, policies. *Assistant Professor, Department of Computer Science, Dr.NGP Arts & Science College, Coimbatore, TN, India. Vol. 4 | No. 3 | March 2015 www.garph.co.uk IJARMSS | 11 International Journal of Advanced Research in ISSN: 2278-6236 Management and Social Sciences Impact Factor: 4.400 SCHOOLS OF THOUGHT IN THE PHILOSOPHY OF EDUCATION Many thoughts are being followed across the world in this regard. Today debates are going among educators on issues like whether the students should study either in relation to virtue or in relation to the best of life (materialistic benefits), whether their education ought to be directed move towards the intellect than towards character of soul? In these thoughts five are highly discussed and those are; essentialism, progressivism, perennialism, existentialism and behaviourism.