Pond-Breeding Amphibian Guild

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pond-Breeding Amphibian Guild

Supplemental Volume: Species of Conservation Concern SC SWAP 2015 Pond-breeding Amphibians Guild Primary Species: Flatwoods Salamander Ambystoma cingulatum Carolina Gopher Frog Rana capito capito Broad-Striped Dwarf Siren Pseudobranchus striatus striatus Tiger Salamander Ambystoma tigrinum Secondary Species: Upland Chorus Frog Pseudacris feriarum -Coastal Plain only Northern Cricket Frog Acris crepitans -Coastal Plain only Contributors (2005): Stephen Bennett and Kurt A. Buhlmann [SCDNR] Reviewed and Edited (2012): Stephen Bennett (SCDNR), Kurt A. Buhlmann (SREL), and Jeff Camper (Francis Marion University) DESCRIPTION Taxonomy and Basic Descriptions This guild contains 4 primary species: the flatwoods salamander, Carolina gopher frog, dwarf siren, and tiger salamander; and 2 secondary species: upland chorus frog and northern cricket frog. Primary species are high priority species that are directly tied to a unifying feature or habitat. Secondary species are priority species that may occur in, or be related to, the unifying feature at some time in their life. The flatwoods salamander—in particular, the frosted flatwoods salamander— and tiger salamander are members of the family Ambystomatidae, the mole salamanders. Both species are large; the tiger salamander is the largest terrestrial salamander in the eastern United States. The Photo by SC DNR flatwoods salamander can reach lengths of 9 to 12 cm (3.5 to 4.7 in.) as an adult. This species is dark, ranging from black to dark brown with silver-white reticulated markings (Conant and Collins 1991; Martof et al. 1980). The tiger salamander can reach lengths of 18 to 20 cm (7.1 to 7.9 in.) as an adult; maximum size is approximately 30 cm (11.8 in.). -

Summary of Amphibian Community Monitoring at Canaveral National Seashore, 2009

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Natural Resource Program Center Summary of Amphibian Community Monitoring at Canaveral National Seashore, 2009 Natural Resource Data Series NPS/SECN/NRDS—2010/098 ON THE COVER Clockwise from top left, Hyla chrysoscelis (Cope’s grey treefrog), Hyla gratiosa (barking treefrog), Scaphiopus holbrookii (Eastern spadefoot), and Hyla cinerea (Green treefrog). Photographs by J.D. Willson. Summary of Amphibian Community Monitoring at Canaveral National Seashore, 2009 Natural Resource Data Series NPS/SECN/NRDS—2010/098 Michael W. Byrne, Laura M. Elston, Briana D. Smrekar, Brent A. Blankley, and Piper A. Bazemore USDI National Park Service Southeast Coast Inventory and Monitoring Network Cumberland Island National Seashore 101 Wheeler Street Saint Marys, Georgia, 31558 October 2010 U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service Natural Resource Program Center Fort Collins, Colorado The National Park Service, Natural Resource Program Center publishes a range of reports that address natural resource topics of interest and applicability to a broad audience in the National Park Service and others in natural resource management, including scientists, conservation and environmental constituencies, and the public. The Natural Resource Data Series is intended for timely release of basic data sets and data summaries. Care has been taken to assure accuracy of raw data values, but a thorough analysis and interpretation of the data has not been completed. Consequently, the initial analyses of data in this report are provisional and subject to change. All manuscripts in the series receive the appropriate level of peer review to ensure that the information is scientifically credible, technically accurate, appropriately written for the intended audience, and designed and published in a professional manner. -

Spotted Chorus Frog

This Article From Reptile & Amphibian Profiles From February, 2005 The Cross Timbers Herpetologist Newsletter of the Dallas-Fort Worth Herpetological Society Dallas-Fort Worth Herpetological Society is a 501(c)3 nonprofit organiza- tion whose mission is: To promote understanding, appreciation, and conservation Spotted Chorus Frog ( Pseudacris clarkii ) of reptiles and amphibians, to encourage respect for their By Michael Smith habitats, and to foster respon- Texas winters can be cold, with biting loud for a frog of such small size. As the frogs sible captive care. winds and the occasional ice storm. But Texas brace against prairie grasses in the shallow wa- winters are often like the tiny north Texas ter, the throats of the males expand into an air- towns of Santo or Venus – you see them com- filled sac and call “wrret…wrret…wrret” to All articles and photos remain ing down the road, but if you blink twice nearby females. under the copyright of the au- you’ve missed them. And so, by February we Spotted chorus frogs are among the small thor and photographer. This often have sunny days where a naturalist’s and easily overlooked herps of our area, but publication may be redistributed thoughts turn to springtime. Those earliest they are beautiful animals with interesting life- in its original form, but to use the sunny days remind us that life and color will article or photos, please contact: return to the fields and woods. styles. [email protected] In late February or early March, spring Classification rains begin, and water collects in low places. -

Notophthalmus Perstriatus) Version 1.0

Species Status Assessment for the Striped Newt (Notophthalmus perstriatus) Version 1.0 Striped newt eft. Photo credit Ryan Means (used with permission). May 2018 U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Region 4 Jacksonville, Florida 1 Acknowledgements This document was prepared by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s North Florida Field Office with assistance from the Georgia Field Office, and the striped newt Species Status Assessment Team (Sabrina West (USFWS-Region 8), Kaye London (USFWS-Region 4) Christopher Coppola (USFWS-Region 4), and Lourdes Mena (USFWS-Region 4)). Additionally, valuable peer reviews of a draft of this document were provided by Lora Smith (Jones Ecological Research Center) , Dirk Stevenson (Altamaha Consulting), Dr. Eric Hoffman (University of Central Florida), Dr. Susan Walls (USGS), and other partners, including members of the Striped Newt Working Group. We appreciate their comments, which resulted in a more robust status assessment and final report. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This Species Status Assessment (SSA) is an in-depth review of the striped newt's (Notophthalmus perstriatus) biology and threats, an evaluation of its biological status, and an assessment of the resources and conditions needed to maintain species viability. We begin the SSA with an understanding of the species’ unique life history, and from that we evaluate the biological requirements of individuals, populations, and species using the principles of population resiliency, species redundancy, and species representation. All three concepts (or analogous ones) apply at both the population and species levels, and are explained that way below for simplicity and clarity as we introduce them. The striped newt is a small salamander that uses ephemeral wetlands and the upland habitat (scrub, mesic flatwoods, and sandhills) that surrounds those wetlands. -

The Origins of Chordate Larvae Donald I Williamson* Marine Biology, University of Liverpool, Liverpool L69 7ZB, United Kingdom

lopmen ve ta e l B Williamson, Cell Dev Biol 2012, 1:1 D io & l l o l g DOI: 10.4172/2168-9296.1000101 e y C Cell & Developmental Biology ISSN: 2168-9296 Research Article Open Access The Origins of Chordate Larvae Donald I Williamson* Marine Biology, University of Liverpool, Liverpool L69 7ZB, United Kingdom Abstract The larval transfer hypothesis states that larvae originated as adults in other taxa and their genomes were transferred by hybridization. It contests the view that larvae and corresponding adults evolved from common ancestors. The present paper reviews the life histories of chordates, and it interprets them in terms of the larval transfer hypothesis. It is the first paper to apply the hypothesis to craniates. I claim that the larvae of tunicates were acquired from adult larvaceans, the larvae of lampreys from adult cephalochordates, the larvae of lungfishes from adult craniate tadpoles, and the larvae of ray-finned fishes from other ray-finned fishes in different families. The occurrence of larvae in some fishes and their absence in others is correlated with reproductive behavior. Adult amphibians evolved from adult fishes, but larval amphibians did not evolve from either adult or larval fishes. I submit that [1] early amphibians had no larvae and that several families of urodeles and one subfamily of anurans have retained direct development, [2] the tadpole larvae of anurans and urodeles were acquired separately from different Mesozoic adult tadpoles, and [3] the post-tadpole larvae of salamanders were acquired from adults of other urodeles. Reptiles, birds and mammals probably evolved from amphibians that never acquired larvae. -

A Safe and Efficient Technique for Handling Siren Spp. and Amphiuma

Herpetological Review, 2009, 40(2), 169–170. © 2009 by Society for the Study of Amphibians and Reptiles A Safe and Efficient Technique for Handling Siren spp. and Amphiuma spp. in the Field DONALD J. BROWN* and MICHAEL R. J. FORSTNER Department of Biology, Texas State University-San Marcos 601 University Drive, San Marcos, Texas 78666, USA e-mail (MRJF): [email protected] FIG. 1. Siren texana being restrained for measurements using a snake Corresponding author; e-mail: [email protected] tube. Siren spp. and Amphiuma spp. are large eel-like salamanders sary data on a given individual in under ten minutes. A potential distributed throughout the coastal plain of the southeastern United drawback of this method is that the salamanders will never be States (Conant and Collins 1998). Much has been reported on perfectly linear due to the necessity of having enough space to capture methods for these species. Common methods include min- facilitate movement into the tube. However, once an individual is now and crayfish traps (Sorensen 2004), hoop nets (Snodgrass et placed in a given tube, a smaller tube can be inserted at the anterior al. 1999), dip nets (Fauth and Resetarits 1991), and baited hooks end and the salamander can be coerced into it by touching its tail, (Hanlin 1978). Recently, a trap capable of sampling these species resulting in a tighter fit and more accurate measurements. The at depths up to 70 cm was developed (Luhring and Jennison 2008). handling method we used was effective for collecting standard Because of their slippery skin and irritable nature, Siren spp. -

Reproductive Biology of the Southern Dwarf Siren, Pseudobranchus Axanthus, in Southern Florida Zachary Cole Adcock University of South Florida, [email protected]

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School January 2012 Reproductive Biology of the Southern Dwarf Siren, Pseudobranchus axanthus, in Southern Florida Zachary Cole Adcock University of South Florida, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the American Studies Commons, and the Biology Commons Scholar Commons Citation Adcock, Zachary Cole, "Reproductive Biology of the Southern Dwarf Siren, Pseudobranchus axanthus, in Southern Florida" (2012). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/3941 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Reproductive Biology of the Southern Dwarf Siren, Pseudobranchus axanthus, in Southern Florida by Zachary C. Adcock A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science Department of Integrative Biology College of Arts and Sciences University of South Florida Co-Major Professor: Earl D. McCoy, Ph.D. Co-Major Professor: Henry R. Mushinsky, Ph.D. Stephen M. Deban, Ph.D. Date of Approval: July 10, 2012 Keywords: aquatic salamander, life history, oviposition, clutch size, size at maturity Copyright © 2012, Zachary C. Adcock ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I thank my co-major professors, Henry Mushinsky and Earl McCoy, for their patience and guidance through a couple of thesis projects lasting several years. I also thank my committee member, Steve Deban, for providing excellent comments to improve this thesis document. -

Species of Greatest Conservation Need Species Accounts

2 0 1 5 – 2 0 2 5 Species of Greatest Conservation Need Species Accounts Appendix 1.4C-Amphibians Amphibian Species of Greatest Conservation Need Maps: Physiographic Provinces and HUC Watersheds Species Accounts (Click species name below or bookmark to navigate to species account) AMPHIBIANS Eastern Hellbender Northern Ravine Salamander Mountain Chorus Frog Mudpuppy Eastern Mud Salamander Upland Chorus Frog Jefferson Salamander Eastern Spadefoot New Jersey Chorus Frog Blue-spotted Salamander Fowler’s Toad Western Chorus Frog Marbled Salamander Northern Cricket Frog Northern Leopard Frog Green Salamander Cope’s Gray Treefrog Southern Leopard Frog The following Physiographic Province and HUC Watershed maps are presented here for reference with conservation actions identified in the species accounts. Species account authors identified appropriate Physiographic Provinces or HUC Watershed (Level 4, 6, 8, 10, or statewide) for specific conservation actions to address identified threats. HUC watersheds used in this document were developed from the Watershed Boundary Dataset, a joint project of the U.S. Dept. of Agriculture-Natural Resources Conservation Service, the U.S. Geological Survey, and the Environmental Protection Agency. Physiographic Provinces Central Lowlands Appalachian Plateaus New England Ridge and Valley Piedmont Atlantic Coastal Plain Appalachian Plateaus Central Lowlands Piedmont Atlantic Coastal Plain New England Ridge and Valley 675| Appendix 1.4 Amphibians Lake Erie Pennsylvania HUC4 and HUC6 Watersheds Eastern Lake Erie -

Optimal Swimming Speed Estimates in the Early Permian Mesosaurid

This article was downloaded by: [Joaquín Villamil] On: 24 August 2015, At: 10:09 Publisher: Taylor & Francis Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: 5 Howick Place, London, SW1P 1WG Historical Biology: An International Journal of Paleobiology Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/ghbi20 Optimal swimming speed estimates in the Early Permian mesosaurid Mesosaurus tenuidens (Gervais 1865) from Uruguay Joaquín Villamilab, Pablo Núñez Demarcoc, Melitta Meneghela, R. Ernesto Blancobd, Washington Jonesbe, Andrés Rinderknechtbe, Michel Laurinf & Graciela Piñeirog a Laboratorio de Sistemática e Historia Natural de Vertebrados, IECA, Facultad de Ciencias, Universidad de la República, Montevideo, Uruguay b Núcleo de Biomecánica, Espacio Interdisciplinario, Montevideo, Uruguay c Click for updates Facultad de Ciencias, Departamento de Geología, Montevideo, Uruguay d Facultad de Ciencias, Instituto de Física, Montevideo, Uruguay e Museo Nacional de Historia Natural, Montevideo, Uruguay f CR2P, Sorbonne Universités, CNRS/MNHN/UPMC, Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle, Paris, France g Facultad de Ciencias, Departamento de Evolución de Cuencas, Montevideo, Uruguay Published online: 14 Aug 2015. To cite this article: Joaquín Villamil, Pablo Núñez Demarco, Melitta Meneghel, R. Ernesto Blanco, Washington Jones, Andrés Rinderknecht, Michel Laurin & Graciela Piñeiro (2015): Optimal swimming speed estimates in the Early Permian mesosaurid Mesosaurus tenuidens (Gervais 1865) from Uruguay, Historical Biology: An International Journal of Paleobiology, DOI: 10.1080/08912963.2015.1075018 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08912963.2015.1075018 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Taylor & Francis makes every effort to ensure the accuracy of all the information (the “Content”) contained in the publications on our platform. -

Postbreeding Movements of the Dark Gopher Frog, Rana Sevosa Goin and Netting: Implications for Conservation and Management

Journal o fieryefology, Vol. 35, No. 2, pp. 336-321, 2001 CopyriJt 2001 Society for the Study of Amphibians and Reptiles Postbreeding Movements of the Dark Gopher Frog, Rana sevosa Goin and Netting: Implications for Conservation and Management 'Departmmzt of Biological Sciences, Southeastern Louisiana Uniwsity, SLU 10736, Hammod, Louisiamla 70403-0736, USA 4USDA Forest Service, Southern Research Station, Southern Institute of Forest Genetics, 23332 Highmy 67, Saucier, Mississippi 39574, USA ABSTRACT.-Conservation plans for amphibians often focus on activities at the breeding site, but for species that use temstrial habitats for much of the year, an understanding of nonbreeding habitat use is also essential. We used radio telemetry to study the postbreeding movements of individuals of the only known population of dark gopher frogs, Rana sevosa, during two breeding seasons (1994 and 1996). Move- ments away from the pond were relatively short (< 300 m) and usually occurred within a two-day period after frogs initially exited the breeding pond. However, dispersal distances for some individuals may have been constrained by a recent clearcut on adjacent private property. Final recorded locations for all individ- uals were underground retreats associated with stump holes, root mounds of fallen trees, or mammal bur- rows in surrounding upland areas. When implementing a conservation plan for Rana sevosa and other amphibians with similar habitat utilization patterns, we recommend that a temstrial buffer zone of pro- tection include the aquatic breeding site and adjacent nonbreeding season habitat. When the habitat is fragmented, the buffer zone should include additional habitat to lessen edge effects and provide connec- tivity between critical habitats. -

TRAPPING SUCCESS and POPULATION ANALYSIS of Siren Lacertina and Amphiuma Means

TRAPPING SUCCESS AND POPULATION ANALYSIS OF Siren lacertina AND Amphiuma means By KRISTINA SORENSEN A THESIS PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2003 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I thank my committee members Lora Smith, Franklin Percival, and Dick Franz for all their support and advice. The Department of Interior's Student Career Experience Program and the U.S. Geological Survey's Amphibian Research and Monitoring Initiative provided funding for this project. I thank those involved with these programs who have helped me over the last three years: David Trauger, Ken Dodd, Jamie Barichivich, Jennifer Staiger, Kevin Smith, and Steve Johnson. Numerous people helped with field work: Audrey Owens, Maya Zacharow, Chris Gregory, Matt Chopp, Amanda Rice, Paul Loud, Travis Tuten, Steve Johnson, and Jennifer Staiger, Lora Smith, and the UF Wildlife Field Techniques Courses of2001-2002. Paul Moler and John Jensen provided advice and shared their wealth of herpetological knowledge. I thank the staff of Okefenokee National Wildlife Refuge and Steve Coates, manager of the Ordway Preserve, for their assistance on numerous occasions and for permission to conduct research on their property. Marinela Capanu of the IFAS Statistical Consulting Unit assisted with statistical analysis. Julien Martin, Bob Dorazio, Rob Bennets, and Cathy Langtimm provided advice on population analysis. I also thank the administrative staff of the Florida Caribbean Science Center and the Florida Cooperative Fish and Wildlife Research Unit. I am much indebted to all of these people, without whom this thesis would not have been possible. -

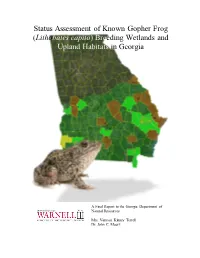

Status Assessment of Known Gopher Frog (Lithobates Capito) Breeding Wetlands and Upland Habitats in Georgia

Status Assessment of Known Gopher Frog (Lithobates capito) Breeding Wetlands and Upland Habitats in Georgia A Final Report to the Georgia Department of Natural Resources Mrs. Vanessa Kinney Terrell Dr. John C. Maerz Final Performance Report State: Georgia Grant No.: Grant Title: Statewide Imperiled Species Grant Duration: 2 years Start Date: July 15, 2013 End Date: July 31, 2015 Period Covering Report: Final Report Project Costs: Federal: State: Total: $4,500 Study/Project Title: Status assessment of known Gopher Frog (Lithobates capito) breeding wetlands and upland habitats in Georgia. GPRA Goals: N/A ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- --------------- *Deviations: Several of the Gopher frog sites that are not located in the site clusters of Ft. Stewart, Ft. Benning, and Ichauway are located on private property. We have visited a subset of these private sites from public roads to obtain GPS coordinates and to visually see the condition of the pond and upland. However, we have not obtained access to dip net these historic sites. Acknowledgements This status assessment relied heavily on the generous collaboration of John Jensen (GA DNR), Lora Smith (Joseph W. Jones Ecological Research Center), Anna McKee (USGS), Beth Schlimm (Orianne Society), Dirk Stevenson (Orianne Society), and Roy King (Ft. Stewart). William Booker and Emily Jolly assisted with ground-truthing of field sites. -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Prepared By: John C Maerz and Vanessa C. K. Terrell Date: 3/1/2016 Study/Project Objective: The objective of this project was to update the known status of Gopher frogs (Lithobates capito) in Georgia by coalescing data on known extant populations from state experts and evaluating wetland and upland habitat conditions at historic and extant localities to determine whether the sites are suitable for sustaining Gopher frog populations.