UMI Films the Original Text Directly from the Copy Submitted

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Netflix and the Development of the Internet Television Network

Syracuse University SURFACE Dissertations - ALL SURFACE May 2016 Netflix and the Development of the Internet Television Network Laura Osur Syracuse University Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/etd Part of the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Osur, Laura, "Netflix and the Development of the Internet Television Network" (2016). Dissertations - ALL. 448. https://surface.syr.edu/etd/448 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the SURFACE at SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations - ALL by an authorized administrator of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Abstract When Netflix launched in April 1998, Internet video was in its infancy. Eighteen years later, Netflix has developed into the first truly global Internet TV network. Many books have been written about the five broadcast networks – NBC, CBS, ABC, Fox, and the CW – and many about the major cable networks – HBO, CNN, MTV, Nickelodeon, just to name a few – and this is the fitting time to undertake a detailed analysis of how Netflix, as the preeminent Internet TV networks, has come to be. This book, then, combines historical, industrial, and textual analysis to investigate, contextualize, and historicize Netflix's development as an Internet TV network. The book is split into four chapters. The first explores the ways in which Netflix's development during its early years a DVD-by-mail company – 1998-2007, a period I am calling "Netflix as Rental Company" – lay the foundations for the company's future iterations and successes. During this period, Netflix adapted DVD distribution to the Internet, revolutionizing the way viewers receive, watch, and choose content, and built a brand reputation on consumer-centric innovation. -

Teaching the Short Story: a Guide to Using Stories from Around the World. INSTITUTION National Council of Teachers of English, Urbana

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 397 453 CS 215 435 AUTHOR Neumann, Bonnie H., Ed.; McDonnell, Helen M., Ed. TITLE Teaching the Short Story: A Guide to Using Stories from around the World. INSTITUTION National Council of Teachers of English, Urbana, REPORT NO ISBN-0-8141-1947-6 PUB DATE 96 NOTE 311p. AVAILABLE FROM National Council of Teachers of English, 1111 W. Kenyon Road, Urbana, IL 61801-1096 (Stock No. 19476: $15.95 members, $21.95 nonmembers). PUB 'TYPE Guides Classroom Use Teaching Guides (For Teacher) (052) Collected Works General (020) Books (010) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC13 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Authors; Higher Education; High Schools; *Literary Criticism; Literary Devices; *Literature Appreciation; Multicultural Education; *Short Stories; *World Literature IDENTIFIERS *Comparative Literature; *Literature in Translation; Response to Literature ABSTRACT An innovative and practical resource for teachers looking to move beyond English and American works, this book explores 175 highly teachable short stories from nearly 50 countries, highlighting the work of recognized authors from practically every continent, authors such as Chinua Achebe, Anita Desai, Nadine Gordimer, Milan Kundera, Isak Dinesen, Octavio Paz, Jorge Amado, and Yukio Mishima. The stories in the book were selected and annotated by experienced teachers, and include information about the author, a synopsis of the story, and comparisons to frequently anthologized stories and readily available literary and artistic works. Also provided are six practical indexes, including those'that help teachers select short stories by title, country of origin, English-languag- source, comparison by themes, or comparison by literary devices. The final index, the cross-reference index, summarizes all the comparative material cited within the book,with the titles of annotated books appearing in capital letters. -

(2016) When Breath Becomes Air Paul Kalanithi

When Breath Becomes Air Paul Kalanithi When Breath Becomes Air Paul Kalanithi Random House Publishing Group (2016) http://ikindlebooks.com When Breath Becomes Air Paul Kalanithi http://ikindlebooks.com When Breath Becomes Air Paul Kalanithi Copyright © 2016 by Corcovado, Inc. Foreword copyright © 2016 by Abraham Verghese All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Random House, an imprint and division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York. RANDOM HOUSE and the HOUSE colophon are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Kalanithi, Paul, author. Title: When breath becomes air / Paul Kalanithi ; foreword by Abraham Verghese. Description: New York : Random House, 2016. Identifiers: LCCN 2015023815 | ISBN 9780812988406 (hardback) | ISBN 9780812988413 (ebook) Subjects: LCSH: Kalanithi, Paul—Health. | Lungs—Cancer—Patients—United States—Biography. | Neurosurgeons—Biography. | Husband and wife. | BISAC: BIOGRAPHY & AUTOBIOGRAPHY / Personal Memoirs. | MEDICAL / General. | SOCIAL SCIENCE / Death & Dying. Classification: LCC RC280.L8 K35 2016 | DDC 616.99/424—dc23 LC record available at http://lccn.loc.gov/2015023815 eBook ISBN 9780812988413 randomhousebooks.com Book design by Liz Cosgrove, adapted for eBook Cover design: Rachel Ake v4.1 ep http://ikindlebooks.com When Breath Becomes Air Paul Kalanithi Contents Cover Title Page Copyright Editor's Note Epigraph Foreword by Abraham Verghese Prologue Part I: In Perfect Health I Begin Part II: Cease Not till Death Epilogue by Lucy Kalanithi Dedication Acknowledgments About the Author http://ikindlebooks.com When Breath Becomes Air Paul Kalanithi EVENTS DESCRIBED ARE BASED on Dr. Kalanithi’s memory of real-world situations. However, the names of all patients discussed in this book—if given at all—have been changed. -

Volume 8, Number 1

POPULAR CULTURE STUDIES JOURNAL VOLUME 8 NUMBER 1 2020 Editor Lead Copy Editor CARRIELYNN D. REINHARD AMY DREES Dominican University Northwest State Community College Managing Editor Associate Copy Editor JULIA LARGENT AMANDA KONKLE McPherson College Georgia Southern University Associate Editor Associate Copy Editor GARRET L. CASTLEBERRY PETER CULLEN BRYAN Mid-America Christian University The Pennsylvania State University Associate Editor Reviews Editor MALYNNDA JOHNSON CHRISTOPHER J. OLSON Indiana State University University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Associate Editor Assistant Reviews Editor KATHLEEN TURNER LEDGERWOOD SARAH PAWLAK STANLEY Lincoln University Marquette University Associate Editor Graphics Editor RUTH ANN JONES ETHAN CHITTY Michigan State University Purdue University Please visit the PCSJ at: mpcaaca.org/the-popular-culture-studies-journal. Popular Culture Studies Journal is the official journal of the Midwest Popular Culture Association and American Culture Association (MPCA/ACA), ISSN 2691-8617. Copyright © 2020 MPCA. All rights reserved. MPCA/ACA, 421 W. Huron St Unit 1304, Chicago, IL 60654 EDITORIAL BOARD CORTNEY BARKO KATIE WILSON PAUL BOOTH West Virginia University University of Louisville DePaul University AMANDA PICHE CARYN NEUMANN ALLISON R. LEVIN Ryerson University Miami University Webster University ZACHARY MATUSHESKI BRADY SIMENSON CARLOS MORRISON Ohio State University Northern Illinois University Alabama State University KATHLEEN KOLLMAN RAYMOND SCHUCK ROBIN HERSHKOWITZ Bowling Green State Bowling Green State -

Download Free Zip Inner Monologue Part 1 Download Free Zip Inner Monologue Part 1

download free zip inner monologue part 1 Download free zip inner monologue part 1. Completing the CAPTCHA proves you are a human and gives you temporary access to the web property. What can I do to prevent this in the future? If you are on a personal connection, like at home, you can run an anti-virus scan on your device to make sure it is not infected with malware. If you are at an office or shared network, you can ask the network administrator to run a scan across the network looking for misconfigured or infected devices. Another way to prevent getting this page in the future is to use Privacy Pass. You may need to download version 2.0 now from the Chrome Web Store. Cloudflare Ray ID: 67a1ee67bbc116f0 • Your IP : 188.246.226.140 • Performance & security by Cloudflare. Inner monologue examples: Characters’ hidden lives. Internal or inner monologue is a useful literary device. Dialogue reveals character relationships, their converging or competing goals. Inner monologue gives readers more private feelings and dilemmas. Learn more on how to use inner monologue effectively: First, what is ‘inner monologue’? A ‘monologue’ literally means ‘speaking alone’, if we go back to the word’s roots. In a play, especially in Shakespeare, a monologue (such as when the villain Iago in Othello expresses his wicked plans) is often used to reveal a character’s secret thoughts or intentions. In prose, inner monologue typically reveals a character’s private impressions, desires, frustrations or dilemmas. How and why might you use internal monologue? How to use inner monologue in stories: Use inner monologue to reveal unspoken thoughts Describe others from a specific POV Show private dilemmas Reveal self-perception and mentality Show personal associations. -

TV Finales and the Meaning of Endings Casey J. Mccormick

TV Finales and the Meaning of Endings Casey J. McCormick Department of English McGill University, Montréal A thesis submitted to McGill University in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy © Casey J. McCormick Table of Contents Abstract ………………………………………………………………………….…………. iii Résumé …………………………………………………………………..………..………… v Acknowledgements ………………………………………………………….……...…. vii Chapter One: Introducing Finales ………………………………………….……... 1 Chapter Two: Anticipating Closure in the Planned Finale ……….……… 36 Chapter Three: Binge-Viewing and Netflix Poetics …………………….….. 72 Chapter Four: Resisting Finality through Active Fandom ……………... 116 Chapter Five: Many Worlds, Many Endings ……………………….………… 152 Epilogue: The Dying Leader and the Harbinger of Death ……...………. 195 Bibliography ……………………………………………………………………………... 199 Primary Media Sources ………………………………………………………………. 211 iii Abstract What do we want to feel when we reach the end of a television series? Whether we spend years of our lives tuning in every week, or a few days bingeing through a storyworld, TV finales act as sites of negotiation between the forces of media production and consumption. By tracing a history of finales from the first Golden Age of American television to our contemporary era of complex TV, my project provides the first book- length study of TV finales as a distinct category of narrative media. This dissertation uses finales to understand how tensions between the emotional and economic imperatives of participatory culture complicate our experiences of television. The opening chapter contextualizes TV finales in relation to existing ideas about narrative closure, examines historically significant finales, and describes the ways that TV endings create meaning in popular culture. Chapter two looks at how narrative anticipation motivates audiences to engage communally in paratextual spaces and share processes of closure. -

Applying a Rhizomatic Lens to Television Genres

A THOUSAND TV SHOWS: APPLYING A RHIZOMATIC LENS TO TELEVISION GENRES _______________________________________ A Dissertation presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School at the University of Missouri-Columbia _______________________________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy _____________________________________________________ by NETTIE BROCK Dr. Ben Warner, Dissertation Supervisor May 2018 The undersigned, appointed by the dean of the Graduate School, have examined the Dissertation entitled A Thousand TV Shows: Applying A Rhizomatic Lens To Television Genres presented by Nettie Brock A candidate for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy And hereby certify that, in their opinion, it is worthy of acceptance. ________________________________________________________ Ben Warner ________________________________________________________ Elizabeth Behm-Morawitz ________________________________________________________ Stephen Klien ________________________________________________________ Cristina Mislan ________________________________________________________ Julie Elman ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Someone recently asked me what High School Nettie would think about having written a 300+ page document about television shows. I responded quite honestly: “High School Nettie wouldn’t have been surprised. She knew where we were heading.” She absolutely did. I have always been pretty sure I would end up with an advanced degree and I have always known what that would involve. The only question was one of how I was going to get here, but my favorite thing has always been watching television and movies. Once I learned that a job existed where I could watch television and, more or less, get paid for it, I threw myself wholeheartedly into pursuing that job. I get to watch television and talk to other people about it. That’s simply heaven for me. A lot of people helped me get here. -

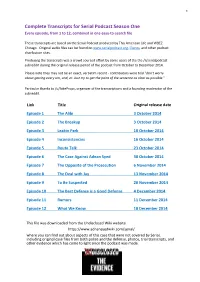

Serial Podcast Season One Every Episode, from 1 to 12, Combined in One Easy-To-Search File

1 Complete Transcripts for Serial Podcast Season One Every episode, from 1 to 12, combined in one easy-to-search file These transcripts are based on the Serial Podcast produced by This American Life and WBEZ Chicago. Original audio files can be found on www.serialpodcast.org, iTunes, and other podcast distribution sites. Producing the transcripts was a crowd sourced effort by some users of the the /r/serialpodcast subreddit during the original release period of the podcast from October to December 2014. Please note they may not be an exact, verbatim record - contributors were told "don't worry about getting every um, and, er. Just try to get the point of the sentence as clear as possible." Particular thanks to /u/JakeProps, organizer of the transcriptions and a founding moderator of the subreddit. Link Title Original release date Episode 1 The Alibi 3 October 2014 Episode 2 The Breakup 3 October 2014 Episode 3 Leakin Park 10 October 2014 Episode 4 Inconsistencies 16 October 2014 Episode 5 Route Talk 23 October 2014 Episode 6 The Case Against Adnan Syed 30 October 2014 Episode 7 The Opposite of the Prosecution 6 November 2014 Episode 8 The Deal with Jay 13 November 2014 Episode 9 To Be Suspected 20 November 2014 Episode 10 The Best Defense is a Good Defense 4 December 2014 Episode 11 Rumors 11 December 2014 Episode 12 What We Know 18 December 2014 This file was downloaded from the Undisclosed Wiki website https://www.adnansyedwiki.com/serial/ where you can find out about aspects of this case that were not covered by Serial, including original case files from both police and the defense, photos, trial transcripts, and other evidence which has come to light since the podcast was made. -

Julia Michaels Inner Monologue Album Download Julia Michaels Inner Monologue Album Download

julia michaels inner monologue album download Julia michaels inner monologue album download. Completing the CAPTCHA proves you are a human and gives you temporary access to the web property. What can I do to prevent this in the future? If you are on a personal connection, like at home, you can run an anti-virus scan on your device to make sure it is not infected with malware. If you are at an office or shared network, you can ask the network administrator to run a scan across the network looking for misconfigured or infected devices. Another way to prevent getting this page in the future is to use Privacy Pass. You may need to download version 2.0 now from the Chrome Web Store. Cloudflare Ray ID: 66a109d48c5d1600 • Your IP : 188.246.226.140 • Performance & security by Cloudflare. MQS Albums Download. Mastering Quality Sound,Hi-Res Audio Download, 高解析音樂, 高音質の音楽. Julia Michaels – Inner Monologue Part 2 (2019) [FLAC 24bit/44,1kHz] Julia Michaels – Inner Monologue Part 2 (2019) FLAC (tracks) 24-bit/44,1 kHz | Time – 25:08 minutes | 286 MB | Genre: Pop Studio Master, Official Digital Download | Front Cover | © Republic Records. Singer-songwriter Julia Michaels‘ Inner Monologue: Part 1 was one of the year’s most impressive EPs, and the prolific musician has already announced her follow-up. Inner Monologue: Part 2 is due out June 28 via Republic. The announcement follows Michaels’ CMT Award win for Collaborative Video Of The Year for her song “Coming Home” with Keith Urban. In addition to her solo career, Michaels has also written some of the biggest pop hits of the last few years — pretty much every single off Justin Bieber‘s Purpose and the best of Shawn Mendes and Selena Gomez‘s recent releases. -

The Dial 1919

State Normal School FRAMINGHAM ** -.- ARCHIVES Framingham State College Framingham, Massachusetts Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2013 http://archive.org/details/dial1919fram 3 /VO^Y\AJ THE DIAL v^ ^ **--;- • • MM « r /P 3fo Mr. 3frei>ertck W. Sie& we, tlje class of 1010 ftebicate tl|iB Bial in appreciation of Ijis ontiring efforts, sincere sgmpatljjj anb personal interest toward all onr actiuities MR. HENRY W. WHITTEMORE 1898—1917 To Mr. Whitiemore Framingham owes more than to anyone else, the high place which she holds today among Normal Schools. We love to remember him as a counselor and friend to all. I^Hf ^* °j^^H HiTSL '."* l! 1 ';-- E. ^^ ir ^^-" 1 1 ..;;;' •'JB : /'/--.' ' "" ' :' ' "'' : -' ''; : - : :- :, - -?,: -... : DR. JAMES A. CHALMERS Whose every thought is for the interest of the School and "his airls." Foreword /^LASS and faculty members or the com- mittee, alike, have worked hard, and we present to — the class of 9 9 — Dial. you 1 1 The If it helps to while away, or cheer gloomy hours, to recall the old familiar scenes and faces, or to help us, as graduates of the dear old Normal Scl.^ol at Framingham to live more nearly to the ideals for .which our Alma Mater stands, our work will not RaV p been in vain, and our labor will have been well repa!C Editorial Staff Editor-in-Chief Dorothy L. Miner Assistant Editor Dorothy V. Gibson Business Manager Margaret Prendergast Reg. Assistant Business Manager Ruth Stewart H. A. Assistant Business Manager Ruth Gould Faculty Editor Dorothy W. Murdock H. A. Historian Mary Papineau Regular Historian Elizabeth Goodwin H. -

Issues Album Download Zip Drake Views from the 6 Complete Album Mp3 Download #1

issues album download zip Drake Views From The 6 Complete Album Mp3 Download #1. Views From The 6 is an album by Drake which was officially released on April 29, 2016. The first single Summer Sixteen is available for you to download below. Views From the 6 Tracklist: Keep the Family Close 9 U With Me? Feel No Ways Hype Weston Road Flows Redemption With You Faithful Still Here Controlla One Dance Grammys Childs Play Pop Style Too Good Summer Over Interlude Fire & Desire Views Hotline Bling (Bonus) It's been more than two years given that Drake announceded an official workshop album, and fans have been itching to hear just what tunes may be included in the rap artist's newest project, Views From the Six. The Canadian rapper told Wanderer his latest album is coming "imminently," nevertheless, causing widespread speculation regarding what already released singles the "6 God" rapper may consist of in the cd, along with reports of collaborations and potential tune names on Drake's fourth studio album. Drake has 2015 as well as the year hasn't already also involve an official close. To proceed his reign right into the brand-new year, the Toronto rapper can be helping you kickstart your 2016 with his extremely anticipated album, Views From the 6. January is the designated arrival as well as those still nursing a hungover after New Year's Eve will certainly value some tunes to get them into a far better area. If there's something we do understand it's that Noah "40" Shebib, his longtime partner, will have much to do on the manufacturing end of the cd. -

Grief Monologue

Grief Monologue Through the boy’s journey, Extremely Loud And Incredibly Close tries to link the personal with the universal, connecting one story of grief within the larger context of a wounded-but-resilient. This kind of grief is healthy and leads to life. They crash in out of nowhere, sweep me off. “It is about a boy’s journey through grief after his beloved grandmother dies and is full of heart, which will bring salve and light to families with small children in this dark year. Don't forget to put your name below before you start!Good luck!. then finally my own husband. Act 1 Scene 2 (Claudius Monologue) 'Tis sweet and commendable in your nature, Hamlet, To give these mourning duties to your father: But, you must know, your father lost a father;. In this Midrashic Monologue, With the Priestly Blessing, Aaron Finds Forgiveness I will forever remember the moment when forgiveness flowed, compassion triumphed, and holiness showered me like an unexpected rainstorm. There is no right or wrong way to cope with grief—as long as you are not causing yourself harm. When Reali returned to hosting Around The Horn this week, I was struck by how honestly and vulnerably he spoke about loss, grief, and humanity. Stephen Colbert brings his signature satire and comedy to The Late Show with Stephen Colbert, the #1 show in late night, where he talks with an eclectic mix of guests about what is new and relevant in the worlds of politics, entertainment, business, music, technology, and more. We are looking for YOUR stories, artwork, photography, poetry, essays, etc about any of the 5 stages of grief.