SHAKESPEARE, the WELSH, and the EARLY MODERN ENGLISH THEATER, 1590-1615 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfi

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Front.Chp:Corel VENTURA

Book Reviews 145 circumstances, as in his dealings with Polonius, and Rosencrantz and Guild- enstern. Did he not think he was killing the King when he killed Polonius? That too was a chance opportunity. Perhaps Hirsh becomes rather too confined by a rigorous logical analysis, and a literal reading of the texts he deals with. He tends to brush aside all alternatives with an appeal to a logical certainty that does not really exist. A dramatist like Shakespeare is always interested in the dramatic potential of the moment, and may not always be thinking in terms of plot. (But as I suggest above, the textual evidence from plot is ambiguous in the scene.) Perhaps the sentimentalisation of Hamlet’s character (which the author rightly dwells on) is the cause for so many unlikely post-renaissance interpretations of this celebrated soliloquy. But logical rigour can only take us so far, and Hamlet, unlike Brutus, for example, does not think in logical, but emotional terms. ‘How all occasions do inform against me / And spur my dull revenge’ he remarks. Anthony J. Gilbert Claire Jowitt. Voyage Drama and Gender Politics 1589–1642: Real and Imagined Worlds. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2003. Pp 256. For Claire Jowitt, Lecturer in Renaissance literature at University of Wales Aberystwyth, travel drama depicts the exotic and the foreign, but also reveals anxieties about the local and the domestic. In this her first book, Jowitt, using largely new historicist methodology, approaches early modern travel plays as allegories engaged with a discourse of colonialism, and looks in particular for ways in which they depict English concerns about gender, leadership, and national identity. -

TIES of the TUDORS the Influence of Margaret Beaufort and Her Web of Relations on the Formation and Preservation of Tudor Rulership

TIES OF THE TUDORS The Influence of Margaret Beaufort and her Web of Relations on the Formation and Preservation of Tudor Rulership P.V. Smolders Student Number: 1607022 Research Master Thesis, August 2016 Supervisor: Dr. Liesbeth Geevers Leiden University, Institute for History Ties of the Tudors The Influence of Margaret Beaufort and her Web of Relations on the Formation and Preservation of Tudor Rulership. Pauline Vera Smolders Student number 1607022 Breestraat 7 / 2311 CG Leiden Tel: 06 50846696 E-mail: [email protected] Research Master Thesis: Europe, 1000-1800 August 2016 Supervisor: Dr. E.M. Geevers Second reader: Prof. Dr. R. Stein Leiden University, Institute for History Cover: Signature of Margaret Beaufort, taken from her first will, 1472. St John’s Archive D56.195, Cambridge University. 1 Table of Contents List of Abbreviations 3 Introduction 4 1 Kinship Networks 11 1.1 The Beaufort Family 14 1.2 Marital Families 18 1.3 The Impact of Widowhood 26 1.4 Conclusion 30 2 Patronage Networks 32 2.1 Margaret’s Household 35 2.2 The Court 39 2.3 The Cambridge Network 45 2.4 Margaret’s Wills 51 2.5 Conclusion 58 3 The Formation and Preservation of Tudor Rulership 61 3.1 Margaret’s Reputation and the Role of Women 62 3.2 Mother and Son 68 3.3 Preserving Tudor Rulership 73 3.4 Conclusion 76 Conclusion 78 Bibliography 82 Appendixes 88 2 Abbreviations BL British Library CUL Cambridge University Library PRO Public Record Office RP Rotuli Parliamentorum SJC St John’s College Archives 3 Introduction A wife, mother of a king, landowner, and heiress, Margaret of Beaufort was nothing if not a versatile women that has interested historians for centuries. -

19Tf? Annual Colorado Shakespeare 5®Stii>A(

19tf? Annual Colorado Shakespeare 5®stii>a( The Comedy of Errors • The Tempest • King John DEPARTMENT OF THEATRE AND DANCE c n L n u a n o s rxjkesn«ciK« University of Colorado® Boulder, Colorado 80309 |Zc?sti'waL Summer 1976 Dear Lover of Shakespeare’s Works: Those who truly love Shakespeare in the theatre will be pleased to learn about the CSh A n nual, a scholarly journal devoted to the art of producing Shakespeare for contemporary audi ences. Eighteen years of experience performing all the Shakespeare plays in the Mary Rip- pon Theatre leave us with a vivid realization of the extent to which the full appreciation of Shakespeare’s content and craftsmanship is dependent on relating to his work in the context for which it was written—the artistic transaction of theatrical production. A significant part of Shakespeare’s greatness has been his capacity to speak meaningfully and movingly to successive generations and diverse cultures. On whatever pedestals we would put him, we must certainly maintain a place for him in our contemporary theatres. His work calls for actors and scenic artists, stages and audiences. It also warrants the attention of those whose scholarship can reflect their practice of his own theatrical art and their sharing of his commitment to make scripts come alive in the theatre. To stimulate such at tention and to make available to others the fruits of such attention—these are the goals of the CSF Annual. The A nnual will grow out of each Colorado Shakespeare Festival. Its basic format will consist of three sections. -

The Cultural and Ideological Significance of Representations of Boudica During the Reigns of Elizabeth I and James I

EXETER UNIVERSITY AND UNIVERSITÉ D’ORLÉANS The Cultural and Ideological Significance Of Representations of Boudica During the reigns of Elizabeth I and James I. Submitted by Samantha FRENEE-HUTCHINS to the universities of Exeter and Orléans as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English, June 2009. This thesis is available for library use on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgment. I certify that all material in this thesis which is not my own work has been identified and that no material has previously been submitted and approved for the award of a degree by this or any other University. ..................................... (signature) 2 Abstract in English: This study follows the trail of Boudica from her rediscovery in Classical texts by the humanist scholars of the fifteenth century to her didactic and nationalist representations by Italian, English, Welsh and Scottish historians such as Polydore Virgil, Hector Boece, Humphrey Llwyd, Raphael Holinshed, John Stow, William Camden, John Speed and Edmund Bolton. In the literary domain her story was appropriated under Elizabeth I and James I by poets and playwrights who included James Aske, Edmund Spenser, Ben Jonson, William Shakespeare, A. Gent and John Fletcher. As a political, religious and military figure in the middle of the first century AD this Celtic and regional queen of Norfolk is placed at the beginning of British history. In a gesture of revenge and despair she had united a great number of British tribes and opposed the Roman Empire in a tragic effort to obtain liberty for her family and her people. -

Catalogue of Photographs of Wales and the Welsh from the Radio Times

RT1 Royal Welsh Show Bulls nd RT2 Royal Welsh Show Sheep shearing nd RT3 Royal Welsh Show Ladies choir nd RT4 Royal Welsh Show Folk dance 1992 RT5 Royal Welsh Show Horses nd RT6 Royal Welsh Show Horses 1962 RT7 LLangollen Tilt Dancers 1962 RT8 Llangollen Tilt Estonian folk dance group 1977 RT9 Llangollen Eisteddfod Dancers 1986 RT10 Royal Welsh Show Horse and rider 1986 RT11 Royal Welsh Show Horse 1986 RT12 Royal Welsh Show Pigs 1986 RT13 Royal Welsh Show Bethan Charles - show queen 1986 RT14 Royal Welsh Show Horse 1986 RT15 Royal Welsh Show Sheep shearing 1986 RT16 Royal Welsh Show Sheep shearing 1986 RT17 Royal Welsh Show Produce hall 1986 RT18 Royal Welsh Show Men's tug of war 1986 RT19 Royal Welsh Show Show jumping 1986 RT20 Royal Welsh Show Tractors 1986 RT21 Royal Welsh Show Log cutting 1986 RT22 Royal Welsh Show Ladies in welsh costume, spinning wool 1986 RT23 Royal Welsh Show Horses 1986 RT24 Royal Welsh Show Horses 1986 RT25 Royal Welsh Show Men's tug of war 1986 RT26 Royal Welsh Show Audience 1986 RT27 Royal Welsh Show Horses 1986 RT28 Royal Welsh Show Vehicles 1986 RT29 Royal Welsh Show Sheep 1986 RT30 Royal Welsh Show General public 1986 RT31 Royal Welsh Show Bulls 1986 RT32 Royal Welsh Show Bulls 1986 RT33 Merionethshire Iowerth Williams, shepherd nd RT34 LLandrindod Wells Metropole hotel nd RT35 Ebbw Vale Steel works nd RT36 Llangollen River Dee nd RT37 Llangollen Canal nd RT38 Llangollen River Dee nd RT39 Cardiff Statue of St.David, City Hall nd RT40 Towyn Floods 1990 RT41 Brynmawr Houses and colliery nd RT42 Llangadock Gwynfor Evans, 1st Welsh Nationalist MP 1966 RT43 Gwynedd Fire dogs from Capel Garman nd RT44 Anglesey Bronze plaque from Llyn Cerrigbach nd RT45 Griff Williams-actor nd RT46 Carlisle Tullie House, museum and art gallery nd RT47 Wye Valley Tintern Abbey nd 1 RT48 Pontypool Trevethin church nd RT49 LLangyfelach church nd RT50 Denbighshire Bodnant gardens nd RT51 Denbighshire Glyn Ceiriog nd RT52 Merthyr New factory and Cyfartha castle nd RT53 Porthcawl Harbour nd RT54 Porthcawl Harbour nd RT55 Gower Rhosili bay nd RT56 St. -

Family Tree Maker

Descendants of Beli Mawr Beli Mawr LLud Caswallon [1] [2] [2] [1] Penardun Llyr Adminius Llyr Penardun [3] Bran the [3] Bran the Blessed Blessed [4] [4] Beli Beli [5] [5] Amalech Amalech [6] [7] [6] [7] Eudelen Eugein Eudelen Eugein [8] [9] [8] [9] Eudaf Brithguein Eudaf Brithguein [10] [11] [10] [11] Eliud Dyfwyn Eliud Dyfwyn [12] [13] [12] [13] Outigern Oumun Outigern Oumun [14] [15] [14] [15] Oudicant Anguerit Oudicant Anguerit [16] [17] [16] [17] Ritigern Amgualoyt Ritigern Amgualoyt [18] [19] [18] [19] Iumetal Gurdumn Iumetal Gurdumn [20] [21] [20] [21] Gratus Dyfwn Gratus Dyfwn [22] [23] [22] [23] Erb Guordoli Erb Guordoli [24] [25] [24] [25] Telpuil Doli Telpuil Doli [26] [27] [26] [27] Teuhvant Guorcein Teuhvant Guorcein [28] [29] [28] [29] Tegfan Cein Tegfan Cein [30] [31] [30] [31] Guotepauc Tacit Guotepauc Tacit [32] Coel [33] [34] [32] Coel [33] [34] Hen Ystradwal Paternus Hen Ystradwal Paternus [35] [36] [37] [38] [39] [35] [36] [37] [38] [39] Gwawl Cunedda Garbaniawn Ceneu Edern Gwawl Cunedda Garbaniawn Ceneu Edern [40] Dumnagual [41] [42] [43] [44] [45] [36] [35] [40] Dumnagual [41] [42] [43] [44] [45] [36] [35] Moilmut Gurgust Ceneu Masguic Mor Pabo Cunedda Gwawl Moilmut Gurgust Ceneu Masguic Mor Pabo Cunedda Gwawl [46] Bran [47] [48] [49] [50] [51] [52] [53] [54] [55] [56] [57] Tybion ap [58] Edern ap [59] Rhufon ap [60] Dunant ap [61] Einion ap [62] Dogfael ap [63] Ceredig ap [64] Osfael ap [65] Afloeg ap [46] Bran [47] [48] [49] [50] [51] [52] [53] [54] [55] [56] [57] Tybion ap [58] Edern ap [59] Rhufon ap [60] Dunant -

550 to 559 How Maelgwn Became King After the Taking of the Crown

550 to 559 How Maelgwn Became King After the taking of the crown and sceptre of London from the nation of the Cymry, and their expulsion from Lloegyr, they instituted an enquiry to see who of them should be supreme king. The place they appointed was on the Maelgwn sand at Aber Dyvi; and thereto came the men of Gwynedd, the men of Powys, the men of South Wales, of Reinwg of Morganwg, and of d Seisyllwg. And there Maeldav the elder, the son of Ynhwch Unachen, chief of Moel Esgidion in Meirionydd, placed a chair composed of waxed wings under Maelgwn; so when the tide flowed, no one was able to remain, excepting Maelgwn, because of his chair. And by that means Maelgwn became supreme king, with Aberfraw for his principal court; and the earl of Mathraval, and the earl of Dinevwr, and the earl of Caerllion subject to him; and his word paramount over all; and his law paramount, and he not bound to observe their law. And it was on account of Maeldav the elder, that Penardd acquired its privilege, and to be the eldest chansellor-ship. Caradoc of Llancarfan. The Life of St Gildas Crossing the Channel, he spent seven years most successfully in further studies in Gaul. At the end of the seventh year he returned to Great Britain with a great mass of books of all kinds. As the reputation of this highly distinguished stranger spread, scholars poured in to him from all sides. From him they heard the science of the Seven Disciplines most subtly explained, by which doctrine students change into teachers, under the teacher's honour. -

The End of Celtic Britain and Ireland. Saxons, Scots and Norsemen

THE GREATNESS AND DECLINE OF THE CELTS CHAPTER III THE END OF CELTIC BRITAIN AND IRELAND. SAXONS, SCOTS, AND NORSEMEN I THE GERMANIC INVASIONS THE historians lay the blame of bringing the Saxons into Britain on Vortigern, [Lloyd, CCCCXXXVIII, 79. Cf. A. W. W. Evans, "Les Saxons dans l'Excidium Britanniæ", in LVI, 1916, p. 322. Cf. R.C., 1917 - 1919, p. 283; F.Lot, "Hangist, Horsa, Vortigern, et la conquête de la Gde.-Bretagne par les Saxons," in CLXXIX.] who is said to have called them in to help him against the Picts in 449. Once again we see the Celts playing the weak man’s game of putting yourself in the hands of one enemy to save yourself from another. According to the story, Vortigern married a daughter of Hengist and gave him the isle of Thanet and the Kentish coast in exchange, and the alliance between Vortigern and the Saxons came to an end when the latter treacherously massacred a number of Britons at a banquet. Vortigern fled to Wales, to the Ordovices, whose country was then called Venedotia (Gwynedd). They were ruled by a line of warlike princes who had their capita1 at Aberffraw in Anglesey. These kings of Gwynedd, trained by uninterrupted fighting against the Irish and the Picts, seem to have taken on the work of the Dukes of the Britains after Ambrosius or Arthur, and to have been regarded as kings in Britain as a whole. [Lloyd, op. cit., p. 102.] It was apparently at this time that the name of Cymry, which became the national name of the Britons, came to prevail. -

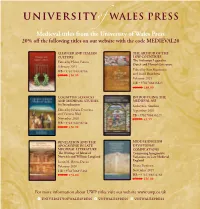

Medieval Titles from the University of Wales Press 20% Off the Following Titles on Our Website with the Code MEDIEVAL20

Medieval titles from the University of Wales Press 20% off the following titles on our website with the code MEDIEVAL20 CHAUCER AND ITALIAN THE ARTHUR OF THE CULTURE LOW COUNTRIES The Arthurian Legend in Edited by Helen Fulton Dutch and Flemish Literature February 2021 HB • 9781786836786 Edited by Bart Besamusca £70.00 £56.00 and Frank Brandsma February 2021 HB • 9781786836823 £80.00 £64.00 COGNITIVE SCIENCES INTRODUCING THE AND MEDIEVAL STUDIES MEDIEVAL ASS An Introduction Kathryn L. Smithies Edited by Juliana Dresvina September 2020 and Victoria Blud PB • 9781786836229 November 2020 £11.99 £9.59 HB • 9781786836748 £70.00 £56.00 REVELATION AND THE MIDDLE ENGLISH APOCALYPSE IN LATE DEVOTIONAL MEDIEVAL LITERATURE COMPILATIONS The Writings of Julian of Composing Imaginative Norwich and William Langland Variations in Late Medieval Justin M. Byron-Davies England February 2020 Diana Denissen HB • 9781786835161 November 2019 £70.00 £56.00 HB • 9781786834768 £70.00 £56.00 For more information about UWP titles visit our website www.uwp.co.uk B UNIVERSITYOFWALESPRESS A UNIWALESPRESS V UNIWALESPRESS 20% OFF WITH THE CODE MEDIEVAL20 TRIOEDD YNYS PRYDEIN GEOFFREY OF MONMOUTH PRINCESSES OF WALES The Triads of the Island of Britain Karen Jankulak Deborah Fisher THE ECONOMY OF MEDIEVAL Edited by Rachel Bromwich PB • 9780708321515 £7.99 £4.00 PB • 9780708319369 £3.99 £2.00 WALES, 1067-1536 PB • 9781783163052 £24.99 £17.49 Matthew Frank Stevens GENDERING THE CRUSADES REVISITING THE MEDIEVAL PB • 9781786834843 £24.99 £19.99 THE WELSH AND Edited by Susan B. Edgington NORTH OF ENGLAND THE MEDIEVAL WORLD and Sarah Lambert Interdisciplinary Approaches INTRODUCING THE MEDIEVAL Travel, Migration and Exile PB • 9780708316986 £19.99 £10.00 Edited by Anita Auer, Denis Renevey, DRAGON Edited by Patricia Skinner Camille Marshall and Tino Oudesluijs Thomas Honegger HOLINESS AND MASCULINITY PB • 9781786831897 £29.99 £20.99 PB • 9781786833945 £35.00 £17.50 PB • 9781786834683 £11.99 £9.59 IN THE MIDDLE AGES 50% OFF WITH THE CODE MEDIEVAL50 Edited by P. -

The Emergence of the Cumbrian Kingdom

The emergence and transformation of medieval Cumbria The Cumbrian kingdom is one of the more shadowy polities of early medieval northern Britain.1 Our understanding of the kingdom’s history is hampered by the patchiness of the source material, and the few texts that shed light on the region have proved difficult to interpret. A particular point of debate is the interpretation of the terms ‘Strathclyde’ and ‘Cumbria’, a matter that has periodically drawn comment since the 1960s. Some scholars propose that the terms were applied interchangeably to the same polity, which stretched from Clydesdale to the Lake District. Others argue that the terms applied to different territories: Strathclyde was focused on the Clyde Valley whereas Cumbria/Cumberland was located to the south of the Solway. The debate has significant implications for our understanding of the extent of the kingdom(s) of Strathclyde/Cumbria, which in turn affects our understanding of politics across tenth- and eleventh-century northern Britain. It is therefore worth revisiting the matter in this article, and I shall put forward an interpretation that escapes from the dichotomy that has influenced earlier scholarship. I shall argue that the polities known as ‘Strathclyde’ and ‘Cumbria’ were connected but not entirely synonymous: one evolved into the other. In my view, this terminological development was prompted by the expansion of the kingdom of Strathclyde beyond Clydesdale. This reassessment is timely because scholars have recently been considering the evolution of Cumbrian identity across a much longer time-period. In 1974 the counties of Cumberland and Westmorland were joined to Lancashire-North-of the-Sands and part of the West Riding of Yorkshire to create the larger county of Cumbria. -

CYMBELINE" in the Fllii^Slhi TI CENTURY

"CYMBELINE" IN THE fllii^SLHi TI CENTURY Bennett Jackson Submitted in partial fulfilment for the de ree of uaster of Arts in the University of Birmingham. October 1971. University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. SYNOPSIS This thesis consists of an Introduction, followed by Part I (chapters 1-2) in which nineteenth- century criticism of the play is discussed, particular attention being paid to Helen Faucit's essay on Imogen, and its relationship to her playing of the role. In Part II the stags-history of Oymbcline in London is traced from 1785 to Irving's Lyceum production of 1896. Directions from promptbooks used by G-.P. Cooke, W.C. Macready, Helen Eaucit, and Samuel ±helps are transcribed and discussed, and in the last chapter the influence of Bernard Shaw on Ellen Terry's Imogen is considered in the light of their correspondence and the actress's rehearsal copies of the play. There are three appendices: a list of performances; transcriptions of two newspaper reviews (from 1843 and 1864) and one private diary (Gordon Crosse's notes on the Lyceum Gymbeline); and discussion of one of the promptbooks prepared for Charles Kean's projected production. -

Download Article

Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research, volume 273 International Conference on Communicative Strategies of Information Society (CSIS 2018) Protestantism and Its Effect on Spiritual Traditions of English-Speaking Countries Alexander Rossinsky Ekaterina Rossinskaya Altai State University Altai State University Barnaul, Russia Barnaul, Russia [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] AbstractThe article raises serious aspects of the relationship the most significant religions with economic conditions, social of the historical and cultural situation in English-speaking factors was German sociologist M. Weber (1884-1920). In one countries in the era of introduction and domination of of his main works, "Protestant Ethics and the Spirit of Protestantism. The article deals with issues related to the Capitalism", he puts forward some positions and conclusions establishment of national identity in the difficult era of the that are still relevant and can to some extent be used to analyze reformation and the assertion of a new morality. Particular the spiritual life of the post-industrial society of the 21st emphasis is placed on the relationship of the rapid development century. of the natural sciences and art and the characteristics of their relationship in the history of England of the 17th century. The It should be noted that at present in various Protestant article analyzes the movement of Protestantism as a reflection of denominations, researchers number more than 800 million the new ideals of the bourgeois era in the context of ethnic and adherents. This is the most heterogeneous branch of aesthetic concepts. Attention is drawn to the features of the Christianity [2].