Henry Keazor —"... If You Could See It, Then You'd Understand?" —Visual Music in Mark Romanek/ Co Id Play, Speed of Sound

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Harem Fantasies and Music Videos: Contemporary Orientalist Representation

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 2007 Harem Fantasies and Music Videos: Contemporary Orientalist Representation Maya Ayana Johnson College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the American Studies Commons, and the Music Commons Recommended Citation Johnson, Maya Ayana, "Harem Fantasies and Music Videos: Contemporary Orientalist Representation" (2007). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539626527. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-nf9f-6h02 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Harem Fantasies and Music Videos: Contemporary Orientalist Representation Maya Ayana Johnson Richmond, Virginia Master of Arts, Georgetown University, 2004 Bachelor of Arts, George Mason University, 2002 A Thesis presented to the Graduate Faculty of the College of William and Mary in Candidacy for the Degree of Master of Arts American Studies Program The College of William and Mary August 2007 APPROVAL PAGE This Thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Maya Ayana Johnson Approved by the Committee, February 2007 y - W ^ ' _■■■■■■ Committee Chair Associate ssor/Grey Gundaker, American Studies William and Mary Associate Professor/Arthur Krrtght, American Studies Cpllege of William and Mary Associate Professor K im b erly Phillips, American Studies College of William and Mary ABSTRACT In recent years, a number of young female pop singers have incorporated into their music video performances dance, costuming, and musical motifs that suggest references to dance, costume, and musical forms from the Orient. -

Gwen Stefani

luam keflezgy artistic director/choreographer selected credits contact: 818 509-0121 < MUSIC VIDEOS > Alicia Keys “Girl on Fire” Dir. Sophie Muller Beyonce “Run the World” Dir. Lawrence Francis Kelly Rowland “Motivation” Dir. Sarah Chatfield Beyonce “Move Your Body” (Asst. Choreographer) Chor. Frank Gatson Dawn Richards “Broken Record” Dir. Sarah McFClogan T Pain, Sophia Fresh “This Instant” Touch & Go J Status ft. Rihanna & Shontelle “Roll” Dir. Vashtie KolaCosmo Joe Buddens, Busta Rhymes, Li’l Mo “Fire” Dir. Paul Hunter Head Automatica “Beating Heart Baby” Dir. Jon Watts TV on the Radio “The Golden Age” Nappy Boy < COMMERCIALS > CK One “Trouble” Macy’s Back to School “The Summer Set” Charter Communication Nair Dir. Jimmy, Humble TV Converse Dir. Andrew Loevenguth Above the Influence Dir. Joaquim Baca-Asay Shoe Carnival Dir. Alex Weil MTV Hip Hop Week (10 Spots) Dir. Antonio MacDonald MTV MC Battle (5 Spots) Dir. Antonio MacDonald Mastercard Promo Campaign Dir. David Coolbirth MTV Direct Effect, Show Intro/ TV Spots Dir. Chike Ozah < TOURS / LIVE SHOWS > Alicia Keys -Set the World on Fire Tour RCA Records Alicia Keys - Europe Promo Tour RCA Records Britney Spears - Femme Fatale Tour Jive Records BET Awards -Kelly Rowland & Trey Songz BET BET Black Girls Rock Awards- Estelle BET Kelly Rowland 2010 Promo Art Director: Frank Gatson Kelly Rowland 2011 International Tour Art Director: Frank Gatson Black Girls Rock Awards- Jill Scott BET Neon Hitch Promo Tour Warner Bros BET Black Girls Rock Awards- Shontelle BET Day 26US Promo Tour Bad Boy BET BGR Awards- VV Brown BET Rihanna (Japan, US Promo Tour 2006) Def Jam Gwen Stefani Tour, opening act Rihanna Def Jam MTV Tempo Concert, Rihanna/Elephant Man Def Jam J Status US Tour (w/ Rihahna) SRP Records Kanye West & John Legend- Webster Hall GOOD Music Shontelle & Rihanna- House of Blues Tour Def Jam, SRP Shontelle & Rihanna- Bajan Music Awards Def Jam, SRP Shontelle & J Status- Rihanna House of Blues Tour < INDUSTRIALS > Athleta 2014 Fashion Week Latin Olympics Cola Cola Moncler, 2010 NY Fashion Week Dir. -

Brett Turnbull - Director of Photography Tel: +44 7796 953 837

Brett Turnbull - Director of Photography tel: +44 7796 953 837 . email: [email protected] website: www.brett-turnbull.com Selected credits Music videos Coldplay “Life in Technicolor II” Dizzee Rascal “Dreams” (CAD award winner 2005 “Best Effects Video”) The Streets “Fit But You Know It” (CAD award winner 2005 “Best Video”) Will Young “Who Am I” Klonherz “ Three Girl Rhumba” Dir: Dougal Wilson Prod: Colonel Blimp / Blink Travis “Re-Offender” Dir: Anton Corbijn Prod: State U2 “Magnificent” (special effects DOP) Kaiser Chiefs “Good Day Bad Days” Dir: Alex Courtes Prod: Partizan Bryan Adams “you’ve Been a Friend to Me” Dir: Bryan Adams Prod: Cheese The Ordinary Boys “Boys Will be Boys” “Life Will be the Death of Me” Dir: Andy Hylton Prod: Exposure The Feeling “Fill My Little World” Dir: Jon Riche Prod: Therapy The Enemy “We’ll Live and Die in These Towns” Dir: Barnaby Roper Prod: Flynn Paul Weller “Wishing on a Star” “From the Floorboards Up” ”Brushed” Dir: Lawrence Watson Prod: Medialab / Get Shorty Robbie Williams “No Regrets” (2nd unit DOP) Dir: Pedro Romanyi Prod: Oil Factory Enya “Trains and Winter Rains” Dir: Rob O’Connor Prod: Stylorouge Calvin Harris “Acceptable in the ‘80’s” Dir: Woof Wan Bau Prod: Nexus Placebo “Every Me Every You” Dir: Matthew Amos Prod: Red Star Urban Species “Woman” Todd Terry “ Something Going On” “It’s Over Love” “Ready For a New Day” Incognito “Nights Over Egypt” Dir: Brett Turnbull Prod: Medialab Live music David Gray “Live at the Apollo” Coldplay “Live in Vancouver” Dir: Hamish Hamilton Prod: Done -

December 2006

“The voice of one crying in the wilderness, Prepare ye the way of the Lord, make His paths straight.” Mark 1:3 CONTENDING FOR Published Monthly CONTENDING FOR FUNDAMENTAL CHRISTIANITY Free Subscription AMERICAN FREEDOM December 2006 “My Tribute to Dad” On Saturday November 4, 2006, from my Daddy’s Bible, I preached his homegoing memorial service at Maranatha Church in Greenville, NC. Mother would like to express deep appreciation to all the pastors, churches, family, and friends that have prayed and supported us all during this time. In the fly leaf of his Bible was written, “I Albert Lee Williamson give my heart to God this 26th day of October 974.” Psalm 116:5 says, “Precious in the sight of the Lord is the death of His saints.” Yes, and Dad was precious to us and we look and long for that glad reunion day! PRESENT WITH THE LORD! “Glory to God in the highest, and on earth peace, good will toward men.” www.thevoiceinthewilderness.org December 2006 • Voice in the Wilderness • Personal Message MY PERSONAL MESSAGE TO YOU Dear friends: calls and do our best to bring Voice in the Wilderness dollars In our Lord’s goodness others with us to the Saviour. to invest in another missionary and grace He allowed me to Your prayers, support, and outreach. return from India in time to be partnership with The Voice in For many years, The Voice with Dad before his passing. the Wilderness enables this in the Wilderness supported part What a joy and comfort to of Sophie’s work in the jungle. -

Gwen Stefani Is Still Showing Us How It’S Done—Woman, Wife, Mother, Designer—All 100 Percent Tabloid-Free

THE ALL-STAR FIFTEEN YEARS AFTER FIRST TOPPING THE CHARTS, NO DOUBT HAS A NEW ALBUM COMING, AND GWEN STEFANI IS STILL SHOWING US HOW IT’S DONE—WOMAN, WIFE, MOTHER, DESIGNER—ALL 100 PERCENT TABLOID-FREE. A ROCK ICON ON AND OFF STAGE, STEFANI TALKS MUSIC AND FASHION AND MAKING THE SLEEVE TO WEAR YOUR HEART ON. BY CANDICE RAINEY PHOTOGRAPHED BY dusan reljin S T Y L E D B Y andrea lieberman E L L E 284 www.elle.com EL0511_WLGwen_MND.indd 284 3/24/11 12:33 PM Beauty Secret: For a vintage-inspired cat- eye, pair liquid liner with doll-like lashes. Try Lineur Intense Liquid Eyeliner and Voluminous Mascara, both in black, by L’Oréal Paris. Left: Knitted jet-stone- beaded top over white-pearl- embroidered tank top and black fringe skirt, Gaultier Paris. Right: Sleeveless silk jumpsuit, Alessandra Rich, $2,200, visit net-a-porter.com. Necklace, Mawi, $645. For details, see Shopping Guide. www.elle.com 285 E L L E EL0511_WLGwen_MND.indd 285 3/24/11 12:33 PM E L L E 286 www.elle.com EL0511_WLGwen_MND.indd 286 3/24/11 12:33 PM Above left and right: Stretch crepe cape dress, L.A.M.B., $425, call 917-463-3553. Brass- plated pendant necklace with cubic zirconia, Noir Jewelry, $230. Leather pumps, Christian Louboutin, $595. Lower left and right: Stretch wool dress with leather trim, Givenchy by Riccardo Tisci, $4,010, at Hirshleifer’s, Manhasset, NY. Leather pumps, Christian Louboutin, $595. For details, see Shopping Guide. HAIR BY DANILO AT THE WALL GROUP; MAKEUP BY CHARLOTTE WILLER AT ART DEPARTMENT; MANICURE BY ELLE AT THE WALL GROUP; PROPS STYLED BY STOCKTON HALL AT 1+1 MGMT; FASHION ASSISTANT: JOAN REIDY www.elle.com 287 E L L E EL0511_WLGwen_MND.indd 287 3/24/11 12:33 PM Chrissie Hynde once said, “If you’re an ugly duckling—and most of us are, in rock bands—you’re not trying to look good. -

1 Direct: 310-993-1790

Direct: 310-993-1790 www.zoebattles.com [email protected] REEL IMDb M U S I C V I D E O S Costume Designer / Key Stylist Director 311 “First Straw” Scott Winig Airbourne “No Way but the Hard Way” Steve Jocz Against Me “I Was a Teenage Anarchist” Marc Klasfeld Apocalyptica “I'm Not Jesus” ft. Corey Taylor Tony Pettrosian Bad Azz “Wrong Idea” ft. Snoop Dogg Jeremy Rall Biffy Clyro “Bubbles” Marc Klasfeld Bloodhound Gang “Foxtrot Uniform Charlie Kilo” Marc Klasfeld By Chance “Baby, it’s on” Lionel C. Martin C-Murder “Back to Life” Dave Meyers Crazy Loop “Joanna (Shut up)” Marc Klasfeld Dave Matthews Band “Tripping Billies” Ken Fox Ee-De “Let’s Get to It” R. Malcom Jones Hozier “From Eden” Henry Chen & Ssong Yang Jay Chou “Double Blade” Alexi Tan Jay Z “Legacy” The Bullitts Jermaine Dupri “It’s Nothin’” ft. DaBrat & R.O.C. Darren Grant Kirk Franklin “Brighter Day” co-stylist: Arnelle Simpson Bille Woodruff Lil Bow Wow “Bounce Wit Me” ft. Jermaine Dupri, Jagged Edge & Da Brat Dave Myers Lil’ Bow Wow “My Baby” ft. Jagged Edge (Jagged Edge-LA) Fats Cats Lil’ Bow Wow “The Don the Dutch” ft. Jagged Edge (Jagged Edge-LA) Fats Cats Liz Primo “State of Amazing” Evan Winter Master P “Oohwee” Terry Heller & Danny Passman Master P “Pockets Gone’ Stay Fat/Golds in They Mouth” co-stylist: Arnelle Simpson Christopher Morrison Mil “Ride Out” ft. Lil’ Wayne, Juvenile, Slim, Beanie Segal & Baby Sylvain White Public Announcement “A Man Ain’t Supposed to Cry” Christopher Erskin Rachelle Ferrell “With Open Arms” Pam Robinson Run the Jewels “Crown” Peter Martin Ruff Endz “No More” Bille Woodruff Seven Mary Three “Wait” John Stockwell Stone Sour “St Marie” Marc Klasfeld Travie McCoy “Billionaire” ft. -

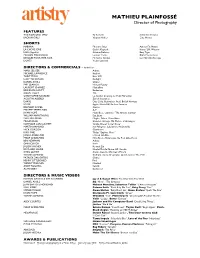

MATHIEU PLAINFOSSÉ Director of Photography

MATHIEU PLAINFOSSÉ Director of Photography FEATURES THE IRON ORCHARD Ty Roberts Santa Rita Pictures RADIUM GIRLS Virginia Mohler Cine Mosaic SHORTS HABANA Edouard Salier Autour De Minuit LA CHOSE SÛRE Cedric Klapisch Irene / J.M. Weston LIGA (Appelle) Cristina Pinheiro Easy Tiger PASSION MECANIQUE Ludovic Piette Bizibi Productions DESOLEE POUR HIER SOIR Hortense Gelinet Les Films Du Kiosque LIGHTS Yoann Lemoine DIRECTORS & COMMERCIALS – Partial List MARK SELIGER Adidas MICHAEL LAWRENCE Reebok THIRTYTWO Ritz, VW LUCY TCHERNIAK Budlight DANIEL ASKILL Chanel PHIL JOANOU Honest Beauty LAURENT CHANEZ Maybelline BRENDAN CANTY Budweiser COLIN TILLEY YSL CHRISTOPHE NAVARRE Lu, Kinder Country, Le Petit Marseillais AGUSTIN ALBERDI Zurich Insurance DARYL Diet Coke, Budweiser, Audi, British Airways SO ME Apple, Nokia N8, Endless Summer BARNABY ROPER Garnier PHILIPPE TEMPELMAN A-Z RYAN HOPE Hugo Boss, Guinness “The Artist’s Journey” WILLIAM ARMSTRONG Eau Jeune MATHIEU CESAR Mugler, Yahoo, Mont Blanc MEGAFORCE Camelot, Orange, M6 Mobile, Volkswagen NATHALIE CANGUILHEM Grazia, Diesel “Lover Dose” MARTIN AAMUND San Pelligrino, Lululemon, McDonalds NICK GORDON Chambord KIKU OHE Thalys “Explore More” JONAS AKERLUND L’Oreal Infaillible PHILIP ANDELMAN Nina Ricci – Nina L’eau, Ike Pod, Ciba Vision BEN NEWMAN Adidas OMRI COHEN Kraft JULIEN ROCHER Renault Zar EDOUARD SALIER Etisalat Mobile Phone, HP, Geodis CYRIL GUYOT Casino Austria, Children’s Motrin YOANN LEMOINE Cadbury, Caisse D’epargne, Lipton, Lipton Thé, Pritt PATRICK DAUGHTERS Chanel HENRY LITTLECHILD Pirel WENDY MORGAN Newfeel ANDY FOGWILL Sunsilk ALAN BIBBY Budweiser DIRECTORS & MUSIC VIDEOS ROMAIN GAVRAS & KIM CHAPIRON Jay Z & Kanye West “No Church In The Wild” DANIEL ASKILL Sia “Alive”, “The Greatest” JEAN-BAPTISTE MONDINO Mahaut Mondino, Sebastien Tellier “L’Amour Naissant” PAUL GORE Paloma Faith “Can’t Rely On You”, Katy Perry “Rise” SOPHIE MULLER Gwen Stefani “Baby Don’t Lie”, Gwen Stefani “Spark The Fire” RYAN HOPE Disclosure Ft. -

Gothic Intertextuality in Shakespears Sister's Music Videos

Text Matters: A Journal of Literature, Theory and Culture Number 10 Literature Goes Pop / Literar(t)y Article 12 Matters 11-24-2020 Stranger Than Fiction: Gothic Intertextuality in Shakespears Sister’s Music Videos Tomasz Fisiak University of Lodz Follow this and additional works at: https://digijournals.uni.lodz.pl/textmatters Part of the Visual Studies Commons, and the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Fisiak, Tomasz. "Stranger Than Fiction: Gothic Intertextuality in Shakespears Sister’s Music Videos." Text Matters: A Journal of Literature, Theory and Culture, no.10, 2020, pp. 194-208, doi:10.18778/ 2083-2931.10.12 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Arts & Humanities Journals at University of Lodz Research Online. It has been accepted for inclusion in Text Matters: A Journal of Literature, Theory and Culture by an authorized editor of University of Lodz Research Online. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Text Matters, Number 10, 2020 http://dx.doi.org/10.18778/2083-2931.10.12 Tomasz Fisiak University of Lodz Stranger Than Fiction: Gothic Intertextuality in Shakespears Sister’s Music Videos1 A BSTR A CT The following article is going to focus on a selection of music videos by Shakespears Sister, a British indie pop band consisting of Siobhan Fahey and Marcella Detroit, which rose to prominence in the late 1980s. This article scrutinizes five of the band’s music videos: “Goodbye Cruel World” (1991), “I Don’t Care” (1992), “Stay” (1992), “All the Queen’s Horses” (2019) and “When She Finds You” (2019; the last two filmed 26 years after the duo’s turbulent split), all of them displaying a strong affinity with Gothicism. -

Record of the Week

Smiling Dancing Everything Is Free All You Need Is Positivity ISSUE 491 / 16 AUGUST 2012 TOP 5 MUST-READ ARTICLES record of the week TuneCore founders Jeff } Settle Down multiple broadsheet features. The superb Price and Peter Wells exit video directed by longterm collaborator the company. (Billboard) No Doubt Sophie Muller is a global priority at Polydor/Interscope MTV and playlisted at 4Music, The Box, } Google to de-emphasize No Doubt return after a decade with Chartshow TV, and a ‘record of the week’ websites of repeat copyright a radio smash that is every bit the on VH1. Over their five albums together offenders. (FT) comeback fans had hoped for. We’re No Doubt have sold over 45 million hooked, and we’re not alone. The Mark albums and notched up 10 Grammy Universal could sell all EMI } ‘Spike’ Stent produced Settle Down is nominations, winning twice. With the bar if regulators rip ‘the heart picking up an exceptional reaction from set high on Settle Down, the return of out of the deal’ (HypeBot) the media, with Kiss playlisting, and the purveyors of hits such as It’s My Life, getting its first spin on Radio1 on Friday Hella Good and Don’t Speak, will act UK albums chart shows } as Annie Mac’s ‘Special Delivery’. A as a massive dose of adrenalin for pop lowest one week sales in major press campaign is confirmed for junkies around the world. Video. history. (NME) release with covers on a host of fashion Released: September 16 (album; Push and Shove and music magazines, as well as September 24) } 64% of US under 18s use YouTube as primary music CONTENTS source, Nielsen reports. -

Laisser Une Place À La Famille, C'est Considérer Qu'elle a Une Expertise

Paraît 4 fois l’an mars - juin - oct - déc 10ième année approches DEC 2019 #40 5 BOUTEILLES DE BIÈRE DE 9PK GAGNEZ !!! VALÉRIE GRIMMIAUX « Souris à la vie et elle te sourira » DOSSIER € L’argent des Frères de la Charité BELEN ARES « Laisser une place à la famille, c’est considérer qu’elle a une expertise» allons au japon Le collègue Sébastien Bourgeois vous emmène pour un voyage à la découverte du Japon. Lisez tout sur les mangas, les films de samouraïs et la culture japonaise à la page 7. ÉDITO PLAN HIVER En ce début novembre, les services sociaux nôtre durant l’été, et certaines nous disent de Namur ont activé leur plan hiver afin ne pas venir uniquement pour se nourrir, d’informer des possibilités, dans les struc- mais aussi pour pouvoir économiser sur tures de leur Réseau, de services divers leur consommation d’énergie, dont la part (augmentation de lits pour l’abri de nuit, est de plus en plus importante dans leur possibilités d’abri le jour, de repas, de co- budget, et ainsi préserver leurs ressources lis, de couvertures, de vêtements...). pour d’autres besoins vitaux (p. ex. : se soi- L'hiver est, en effet, à nos portes et, comme gner, garder une part pour les enfants..). chaque année, les plus démunis cherchent Les enfants, justement ! : ils se demandent à se dépêtrer de leur(s) facture(s) d’énergie. comment ils vont pouvoir les gâter durant Le CPAS a récemment communiqué une les fêtes de fin d’année. forte augmentation de la demande d’aide QUI EST ? au paiement de factures d’énergie. -

24. Jmenný Rejstřík 18 and Life...36, 41

24. Jmenný rejstřík 18 and life...............................................36, 41 Jesus Christ pose....................................36, 39 99 problems............................................36, 43 Jonas Akerlund.......................................40, 42 A tout le monde......................................36, 39 Joseph Kahn.................................................43 ABC........................................................18, 19 Juicebox..................................................36, 41 ABC Rocks...................................................18 Juke Box Jury...............................................17 Adam Bernstein............................................39 Justify my love.......................................36, 38 Adam Jones..................................................39 Justin Timberlake.........................................20 Aerosmith...............................................36, 41 Kritika...........................................................19 Agenda suicide.......................................36, 40 KROQ Listeners...........................................40 Album Tracks...............................................18 Lacquer head..........................................36, 39 American life..........................................36, 40 Les Claypool................................................39 Amsterdam.............................................36, 39 Little X.........................................................42 audiovizuální..................12, 14, -

Daniel Landin, Bsc Director of Photography

Lux Artists Ltd. 12 Stephen Mews London W1T 1AH +44 (0)20 7637 9064 www.luxartists.net DANIEL LANDIN, BSC DIRECTOR OF PHOTOGRAPHY FILM/TELEVISION DIRECTOR PRODUCER THE YELLOW BIRDS Alexandre Moors Strong Mining & Winner, Best Cinematography, Sundance Film Festival (2017) Supply Co. UNDER THE SKIN Jonathan Glazer FilmFour/A24 Nominated, Outstanding British Film, BAFTA Awards (2015) Official Selection, Venice Film Festival (2014) Official Selection, London Film Festival (2014) 44 INCH CHEST Malcolm Venville Anonymous Content THE ORGAN GRINDER'S Dinos Chapman Warp Films MONKEY THE UNINVITED The Guard Brothers DreamWorks Goldcrest Pictures DIRECTORS/COMMERCIALS (Selected Credits) JONATHAN GLAZER Nike, Sony, Motorola, Stella Artois, Levi's, Guinness, Wrangler, VW, Flake DOUGAL WILSON John Lewis, Paralympics GUARD BROTHERS Nokia, N- Gage, Captain Morgan, Intel, Nike NICOLAI FUGLSIG Toyota, Mercedes, Audi ALISON MCCLEAN Phileas Fogg TOM HOOPER Jaguar, Jaguar V6 AMIR CHAMDIN H&M, Mango ANDREW DOUGLAS Apple ANTHONY ATANASIO Levi's, Nintendo, Jacques Varbre AOIFE MCARDLE Samsung TRAKTOR Cravendale, Sky, C.O.I. ATANASIO + MARTINEZ Etihad BENITO MONTORIO BBC Trailer, BBC Iplayer BRETT FORAKER Toyota, Sony CHRIS CAIRNS Audi NICK & WARREN Johnny Walker, BMW, Lancome, Schwepps, Thierry Mugler CHRIS HEWITT Stella Artois CHRIS PALMER Kidsco, Honda, Shell, Europcar, PMU, Halifax DANIEL KLEINMAN Tango, Lynx DANTE ARIOLA Orange DAWN SHADFORTH Boots DOM & NIC Barnado's, Toyota Corolla FRANK BUDGEN Cancer Research, Honda, British Heart Foundation JIM GILCHRIST