Interview: Sophie Muller

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

AC/DC You Shook Me All Night Long Adele Rolling in the Deep Al Green

AC/DC You Shook Me All Night Long Adele Rolling in the Deep Al Green Let's Stay Together Alabama Dixieland Delight Alan Jackson It's Five O'Clock Somewhere Alex Claire Too Close Alice in Chains No Excuses America Lonely People Sister Golden Hair American Authors The Best Day of My Life Avicii Hey Brother Bad Company Feel Like Making Love Can't Get Enough of Your Love Bastille Pompeii Ben Harper Steal My Kisses Bill Withers Ain't No Sunshine Lean on Me Billy Joel You May Be Right Don't Ask Me Why Just the Way You Are Only the Good Die Young Still Rock and Roll to Me Captain Jack Blake Shelton Boys 'Round Here God Gave Me You Bob Dylan Tangled Up in Blue The Man in Me To Make You Feel My Love You Belong to Me Knocking on Heaven's Door Don't Think Twice Bob Marley and the Wailers One Love Three Little Birds Bob Seger Old Time Rock & Roll Night Moves Turn the Page Bobby Darin Beyond the Sea Bon Jovi Dead or Alive Living on a Prayer You Give Love a Bad Name Brad Paisley She's Everything Bruce Springsteen Glory Days Bruno Mars Locked Out of Heaven Marry You Treasure Bryan Adams Summer of '69 Cat Stevens Wild World If You Want to Sing Out CCR Bad Moon Rising Down on the Corner Have You Ever Seen the Rain Looking Out My Backdoor Midnight Special Cee Lo Green Forget You Charlie Pride Kiss an Angel Good Morning Cheap Trick I Want You to Want Me Christina Perri A Thousand Years Counting Crows Mr. -

Songs by Artist

Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title &, Caitlin Will 12 Gauge Address In The Stars Dunkie Butt 10 Cc 12 Stones Donna We Are One Dreadlock Holiday 19 Somethin' Im Mandy Fly Me Mark Wills I'm Not In Love 1910 Fruitgum Co Rubber Bullets 1, 2, 3 Redlight Things We Do For Love Simon Says Wall Street Shuffle 1910 Fruitgum Co. 10 Years 1,2,3 Redlight Through The Iris Simon Says Wasteland 1975 10, 000 Maniacs Chocolate These Are The Days City 10,000 Maniacs Love Me Because Of The Night Sex... Because The Night Sex.... More Than This Sound These Are The Days The Sound Trouble Me UGH! 10,000 Maniacs Wvocal 1975, The Because The Night Chocolate 100 Proof Aged In Soul Sex Somebody's Been Sleeping The City 10Cc 1Barenaked Ladies Dreadlock Holiday Be My Yoko Ono I'm Not In Love Brian Wilson (2000 Version) We Do For Love Call And Answer 11) Enid OS Get In Line (Duet Version) 112 Get In Line (Solo Version) Come See Me It's All Been Done Cupid Jane Dance With Me Never Is Enough It's Over Now Old Apartment, The Only You One Week Peaches & Cream Shoe Box Peaches And Cream Straw Hat U Already Know What A Good Boy Song List Generator® Printed 11/21/2017 Page 1 of 486 Licensed to Greg Reil Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title 1Barenaked Ladies 20 Fingers When I Fall Short Dick Man 1Beatles, The 2AM Club Come Together Not Your Boyfriend Day Tripper 2Pac Good Day Sunshine California Love (Original Version) Help! 3 Degrees I Saw Her Standing There When Will I See You Again Love Me Do Woman In Love Nowhere Man 3 Dog Night P.S. -

Humour Investigation: an Analysis of the Theoretical Humour Perspectives, Cultural Continuities, and Developmental Aspects Related to the Comedy of Dawn French

Humour Investigation: An Analysis of the Theoretical Humour Perspectives, Cultural Continuities, and Developmental Aspects Related to the Comedy of Dawn French Thursday, 10 May 2007 Nationally acclaimed former cartoonist and short story writer for The New Yorker, James Thurber, said that “the wit makes fun of other persons; the satirist makes fun of the world; [and] the humorist makes fun of himself” (Moncur, 2007, p. 1). Despite his misogynistic pronoun usage and the obviously unforgivable atrocity of overly Americanizing the spelling of 'humourist,' he did nicely categorize three of the methodological approaches to comedic targets. What Thurber didn't account for, however, were those comedians and comediennes who pay little to no regard for the socially constructed boundaries in form; he didn't account for the wildly transcendental Dawn French. Dawn French was born in October of 1957 in Wales and since early adulthood she has honed her humour skills through numerous television performances, a largely successful sitcom, and feature-length films with her comedic partner in crime Jennifer Saunders (Wikipedia, 2007). Though she started her career in a non- mainstream vain of comedy in the UK, her first major public debut was her starring role as Geraldine Granger on BBC1's 1990s smash situational comedy, The Vicar of Dibley (Wikipedia, 2007). Thus, the majority of her comedy has taken place in very recent times—the mid-to-late 90s and on into the current decade. While she utilizes many different comedic modes and forms, French's humour largely revolves around a few central themes and consequent philosophies. When investigating those themes, it is necessary to view her career as being dichotomously split into the Vicar of Dibley era and the subsequent post-Vicar epoch. -

Rolling Stone Magazine's Top 500 Songs

Rolling Stone Magazine's Top 500 Songs No. Interpret Title Year of release 1. Bob Dylan Like a Rolling Stone 1961 2. The Rolling Stones Satisfaction 1965 3. John Lennon Imagine 1971 4. Marvin Gaye What’s Going on 1971 5. Aretha Franklin Respect 1967 6. The Beach Boys Good Vibrations 1966 7. Chuck Berry Johnny B. Goode 1958 8. The Beatles Hey Jude 1968 9. Nirvana Smells Like Teen Spirit 1991 10. Ray Charles What'd I Say (part 1&2) 1959 11. The Who My Generation 1965 12. Sam Cooke A Change is Gonna Come 1964 13. The Beatles Yesterday 1965 14. Bob Dylan Blowin' in the Wind 1963 15. The Clash London Calling 1980 16. The Beatles I Want zo Hold Your Hand 1963 17. Jimmy Hendrix Purple Haze 1967 18. Chuck Berry Maybellene 1955 19. Elvis Presley Hound Dog 1956 20. The Beatles Let It Be 1970 21. Bruce Springsteen Born to Run 1975 22. The Ronettes Be My Baby 1963 23. The Beatles In my Life 1965 24. The Impressions People Get Ready 1965 25. The Beach Boys God Only Knows 1966 26. The Beatles A day in a life 1967 27. Derek and the Dominos Layla 1970 28. Otis Redding Sitting on the Dock of the Bay 1968 29. The Beatles Help 1965 30. Johnny Cash I Walk the Line 1956 31. Led Zeppelin Stairway to Heaven 1971 32. The Rolling Stones Sympathy for the Devil 1968 33. Tina Turner River Deep - Mountain High 1966 34. The Righteous Brothers You've Lost that Lovin' Feelin' 1964 35. -

The U2 360- Degree Tour and Its Implications on the Concert Industry

THE BIGGEST SHOW ON EARTH: The U2 360- Degree Tour and its implications on the Concert Industry An Undergraduate Honors Thesis by Daniel Dicker Senior V449 Professor Monika Herzig April 2011 Abstract The rock band U2 is currently touring stadiums and arenas across the globe in what is, by all accounts, the most ambitious and expensive concert tour and stage design in the history of the live music business. U2’s 360-Degree Tour, produced and marketed by Live Nation Entertainment, is projected to become the top-grossing tour of all time when it concludes in July of 2011. This is due to a number of different factors that this thesis will examine: the stature of the band, the stature of the ticket-seller and concert-producer, the ambitious and attendance- boosting design of the stage, the relatively-low ticket price when compared with the ticket prices of other tours and the scope of the concert's production, and the resiliency of ticket sales despite a poor economy. After investigating these aspects of the tour, this thesis will determine that this concert endeavor will become a new model for arena level touring and analyze the factors for success. Introduction The concert industry handbook is being rewritten by U2 - a band that has released blockbuster albums and embarked on sell-out concert tours for over three decades - and the largest concert promotion company in the world, Live Nation. This thesis is an examination of how these and other forces have aligned to produce and execute the most impressive concert production and single-most successful concert tour in history. -

Dispatches: Representatives

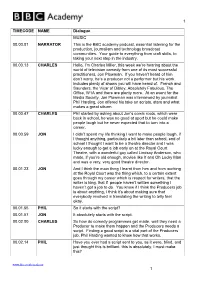

1 TIMECODE NAME Dialogue MUSIC 00.00.01 NARRATOR This is the BBC academy podcast, essential listening for the production, journalism and technology broadcast communities. Your guide to everything from craft skills, to taking your next step in the industry. 00.00.13 CHARLES Hello, I’m Charles Miller, this week we’re hearing about the world of television comedy from one of its most successful practitioners, Jon Plowman. If you haven’t heard of him don’t worry, he’s a producer not a performer but his work includes plenty of shows you will have heard of. French and Saunders, the Vicar of Dibley, Absolutely Fabulous, The Office, W1A and there are plenty more. At an event for the Media Society, Jon Plowman was interviewed by journalist Phil Harding, Jon offered his take on scripts, stars and what makes a great sitcom. 00.00.47 CHARLES Phil started by asking about Jon’s comic roots, which were back in school, he was no good at sport but he could make people laugh but he never expected that to turn into a career. 00.00.59 JON I didn’t spend my life thinking I want to make people laugh, if I thought anything, particularly a bit later than school, end of school I thought I want to be a theatre director and I was lucky enough to get a job early on at the Royal Court Theatre, with a wonderful guy called Lindsay Anderson, who made, if you’re old enough, movies like If and Oh Lucky Man and was a very, very good theatre director. -

MUSIC NOTES: Exploring Music Listening Data As a Visual Representation of Self

MUSIC NOTES: Exploring Music Listening Data as a Visual Representation of Self Chad Philip Hall A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of: Master of Design University of Washington 2016 Committee: Kristine Matthews Karen Cheng Linda Norlen Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Art ©Copyright 2016 Chad Philip Hall University of Washington Abstract MUSIC NOTES: Exploring Music Listening Data as a Visual Representation of Self Chad Philip Hall Co-Chairs of the Supervisory Committee: Kristine Matthews, Associate Professor + Chair Division of Design, Visual Communication Design School of Art + Art History + Design Karen Cheng, Professor Division of Design, Visual Communication Design School of Art + Art History + Design Shelves of vinyl records and cassette tapes spark thoughts and mem ories at a quick glance. In the shift to digital formats, we lost physical artifacts but gained data as a rich, but often hidden artifact of our music listening. This project tracked and visualized the music listening habits of eight people over 30 days to explore how this data can serve as a visual representation of self and present new opportunities for reflection. 1 exploring music listening data as MUSIC NOTES a visual representation of self CHAD PHILIP HALL 2 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF: master of design university of washington 2016 COMMITTEE: kristine matthews karen cheng linda norlen PROGRAM AUTHORIZED TO OFFER DEGREE: school of art + art history + design, division -

Songs by Title Karaoke Night with the Patman

Songs By Title Karaoke Night with the Patman Title Versions Title Versions 10 Years 3 Libras Wasteland SC Perfect Circle SI 10,000 Maniacs 3 Of Hearts Because The Night SC Love Is Enough SC Candy Everybody Wants DK 30 Seconds To Mars More Than This SC Kill SC These Are The Days SC 311 Trouble Me SC All Mixed Up SC 100 Proof Aged In Soul Don't Tread On Me SC Somebody's Been Sleeping SC Down SC 10CC Love Song SC I'm Not In Love DK You Wouldn't Believe SC Things We Do For Love SC 38 Special 112 Back Where You Belong SI Come See Me SC Caught Up In You SC Dance With Me SC Hold On Loosely AH It's Over Now SC If I'd Been The One SC Only You SC Rockin' Onto The Night SC Peaches And Cream SC Second Chance SC U Already Know SC Teacher, Teacher SC 12 Gauge Wild Eyed Southern Boys SC Dunkie Butt SC 3LW 1910 Fruitgum Co. No More (Baby I'm A Do Right) SC 1, 2, 3 Redlight SC 3T Simon Says DK Anything SC 1975 Tease Me SC The Sound SI 4 Non Blondes 2 Live Crew What's Up DK Doo Wah Diddy SC 4 P.M. Me So Horny SC Lay Down Your Love SC We Want Some Pussy SC Sukiyaki DK 2 Pac 4 Runner California Love (Original Version) SC Ripples SC Changes SC That Was Him SC Thugz Mansion SC 42nd Street 20 Fingers 42nd Street Song SC Short Dick Man SC We're In The Money SC 3 Doors Down 5 Seconds Of Summer Away From The Sun SC Amnesia SI Be Like That SC She Looks So Perfect SI Behind Those Eyes SC 5 Stairsteps Duck & Run SC Ooh Child SC Here By Me CB 50 Cent Here Without You CB Disco Inferno SC Kryptonite SC If I Can't SC Let Me Go SC In Da Club HT Live For Today SC P.I.M.P. -

Madonna Now President's Report 2012-2013

MADONNA NOW The Magazine of Madonna University PRESIDENT’S REPORT 2012 & 2013 LIVING OUR VALUES On campus, in our community and around the world Thank You to our Generous Sponsors of the 2012 Be Polish for a Night IRA Charitable Rollover Extended Scholarship Dinner and Auction A great way to give to Madonna! If you’re 70 ½ or over, you can make a Diamond Sponsors – $5,000 GoldCorp Inc. tax free gift from your IRA: MJ Diamonds • Direct a qualified distribution (up to $100,000) directly to Madonna Platinum Sponsor – $2,500 • This counts toward your required minimum distribution Felician Sisters of North America • You’ll pay no federal income tax on the distribution Lorraine Ozog • Your gift makes an immediate impact at Madonna Gold Sponsor – $1,000 Comerica Contact us to discuss programs and initiatives DAK Solutions you might want to support. Doc’s Sports Retreat Dean Adkins, Director of Gift Planning Dunkin Donuts/BP Friends of Representative Lesia Liss 734-432-5856 • [email protected] Laurel Manor Miller Canfield Polish National Alliance Lodge 53 Linda Dzwigalski-Long Daniel and Karen Longeway Ray Okonski and Suzanne Sloat SHOW YOUR Leonard C. Suchyta MADONNA PRIDE! Rev. Msgr. Anthony M. Tocco Leave your mark at Madonna with a CBS 62 Detroit/CW50 Legacy Brick in the Path of the Madonna Silver Sponsor – $500 or get an Alumni Spirit Tassel Catholic Vantage Financial Marywood Nursing Center Bricks with your personalized Schakolad Chocolate Factory message are $150 for an 8x8 with SmithGroupJJR Stern Brothers & Co. M logo, and $75 for a 4x8. Spirit Tassels are only $20.13 Bronze Sponsor – $250 Paul and Debbie DeNapoli E & L Construction FOCUS Facility Consulting Services Inc Dr. -

Blssm Paper Artist Statement

!1 of !7 Simon DeBevoise Artist Statement Prof. Maria Sonevytsky 12.12.15 blssm: An Exploration of Cuteness, Consumer Culture and PC Music blssm is an experiment in aesthetics. Tackling a genre of unlimited ambition and excess, I realized quickly that my project could not be a limp imitation of PC Music; the music mandates instead a full-fledged devotion to the “kitsch imagery, catchy hooks, synthetic colours” (Tank Magazine, AG Cook) so central to figures like AG Cook, Hannah Diamond, SOPHIE and GFOTY. I used Hannah Diamond’s “Every Night” as an aural point of reference, reinterpreting the song’s poppy chord progression and setting my tempo to an upbeat 128 bpm. Layering big, shimmering, sawtooth synths over a syncopated kick drum and bass, I created a foundation with which I could engage with the camp and consumerism typically antithetical to the underground music scene yet so integral to the PC Music label. Recreating PC Music’s visual and aural aesthetic, I aim to consider the issues of gender and sexuality at play by framing the genre within discourses on Studio Audio Art, Cyborg Feminism, Japanese Kawaii culture, consumerism, and post-irony. To best introduce the uninformed listener to PC Music (which, importantly, stands for computer music and not politically correct music), I’ve included lyrics from Hannah Diamond’s “Pink and Blue:” We look good in pink and blue You love me, maybe it's true You say, ‘Baby, how are you?’ I’m okay, how about you? DeBevoise !2 of !7 Diamond’s facile rhymes and innocent lyrics craft an image of cuteness and middle-school naivety that play into PC Music’s brand of femininity. -

Directed by Henry Selick; Based on the Novel by Neil Gaiman

Directed by Henry Selick; Based on the novel by Neil Gaiman Production Notes 2 Table of Contents I. Synopsis page 3 II. The Genesis of Coraline page 4 III. Screen Vision page 6 IV. Stop Starts page 7 V. With the Voice Talents of… page 9 VI. Two Worlds, One Studio page 14 VII. On the Set page 23 VIII. Two Worlds, Three Dimensions page 24 IX. Fast Facts page 27 X. Trivia Tips page 28 XI. About the Cast page 29 XII. About the Moviemakers page 33 3 Synopsis Combining the visionary imaginations of two premier fantasists, director Henry Selick (The Nightmare Before Christmas) and author Neil Gaiman (Sandman), Coraline is a wondrous and thrilling, fun and suspenseful adventure that honors and redefines two moviemaking traditions. It is a stop-motion animated feature – and, as the first one to be conceived and photographed in stereoscopic 3-D, unlike anything moviegoers have ever experienced before. Coraline Jones (voiced by Dakota Fanning) is a girl of 11 who is feisty, curious, and adventurous beyond her years. She and her parents (Teri Hatcher, John Hodgman) have just relocated from Michigan to Oregon. Missing her friends and finding her parents to be distracted by their work, Coraline tries to find some excitement in her new environment. She is befriended – or, as she sees it, is annoyed – by a local boy close to her age, Wybie Lovat (Robert Bailey Jr.); and visits her older neighbors, eccentric British actresses Miss Spink and Forcible (Jennifer Saunders and Dawn French) as well as the arguably even more eccentric Russian Mr. -

May 2018 Newsletter

June 18th, 2019 Songwriters in the Round NEWSLETTER A n E n t e r t a i n m e n t I n d u s t r y O r g a n i z a t i on President’s Corner Dear Friends and Members, Our next panel discussion, “Songwriters in the Round,” is set for June 18th at The Federal in North Hollywood. Please note the different venue and the lower price. I am excited to wrap up this season by co-moderating this panel with the amazing, Mara Schwartz Kuge! We take a vacation in the month of July, but next up is our Second Annual Summer Networking Mixer at the Palihouse in West Hollywood on August 27th. Come join us for an entire evening of networking. Bring plenty of business cards and register early—you don’t want to miss this one! Lastly, please join me in thanking our 2018–2019 Board of Directors. These amazing women and men sacrifice so much of their time and energy to ensure that all of the CCC activities are planned and executed without a hitch. Some of their accomplishments are: • Amazing panel discussions with relevant content. • New format that enables the meetings to end promptly at 9pm. • Extended season that now runs from August–June. • New banking partner that offered more favorable rates and lower fees. • The Scholarship Fund is now an official 501(c)(3) non-profit charitable organization. • Producing another rousing Apollo-Award Holiday bash. Thanks for your continued support! I look forward to seeing you at a CCC event soon.