Typology of Think Tanks: a Comparative Study in Finland and Scotland

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

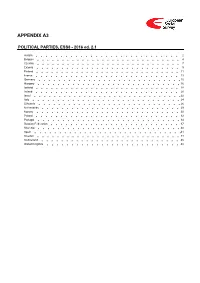

ESS9 Appendix A3 Political Parties Ed

APPENDIX A3 POLITICAL PARTIES, ESS9 - 2018 ed. 3.0 Austria 2 Belgium 4 Bulgaria 7 Croatia 8 Cyprus 10 Czechia 12 Denmark 14 Estonia 15 Finland 17 France 19 Germany 20 Hungary 21 Iceland 23 Ireland 25 Italy 26 Latvia 28 Lithuania 31 Montenegro 34 Netherlands 36 Norway 38 Poland 40 Portugal 44 Serbia 47 Slovakia 52 Slovenia 53 Spain 54 Sweden 57 Switzerland 58 United Kingdom 61 Version Notes, ESS9 Appendix A3 POLITICAL PARTIES ESS9 edition 3.0 (published 10.12.20): Changes from previous edition: Additional countries: Denmark, Iceland. ESS9 edition 2.0 (published 15.06.20): Changes from previous edition: Additional countries: Croatia, Latvia, Lithuania, Montenegro, Portugal, Slovakia, Spain, Sweden. Austria 1. Political parties Language used in data file: German Year of last election: 2017 Official party names, English 1. Sozialdemokratische Partei Österreichs (SPÖ) - Social Democratic Party of Austria - 26.9 % names/translation, and size in last 2. Österreichische Volkspartei (ÖVP) - Austrian People's Party - 31.5 % election: 3. Freiheitliche Partei Österreichs (FPÖ) - Freedom Party of Austria - 26.0 % 4. Liste Peter Pilz (PILZ) - PILZ - 4.4 % 5. Die Grünen – Die Grüne Alternative (Grüne) - The Greens – The Green Alternative - 3.8 % 6. Kommunistische Partei Österreichs (KPÖ) - Communist Party of Austria - 0.8 % 7. NEOS – Das Neue Österreich und Liberales Forum (NEOS) - NEOS – The New Austria and Liberal Forum - 5.3 % 8. G!LT - Verein zur Förderung der Offenen Demokratie (GILT) - My Vote Counts! - 1.0 % Description of political parties listed 1. The Social Democratic Party (Sozialdemokratische Partei Österreichs, or SPÖ) is a social above democratic/center-left political party that was founded in 1888 as the Social Democratic Worker's Party (Sozialdemokratische Arbeiterpartei, or SDAP), when Victor Adler managed to unite the various opposing factions. -

ESS8 Appendix A3 Political Parties Ed

APPENDIX A3 POLITICAL PARTIES, ESS8 - 2016 ed. 2.1 Austria 2 Belgium 4 Czechia 7 Estonia 9 Finland 11 France 13 Germany 15 Hungary 16 Iceland 18 Ireland 20 Israel 22 Italy 24 Lithuania 26 Netherlands 29 Norway 30 Poland 32 Portugal 34 Russian Federation 37 Slovenia 40 Spain 41 Sweden 44 Switzerland 45 United Kingdom 48 Version Notes, ESS8 Appendix A3 POLITICAL PARTIES ESS8 edition 2.1 (published 01.12.18): Czechia: Country name changed from Czech Republic to Czechia in accordance with change in ISO 3166 standard. ESS8 edition 2.0 (published 30.05.18): Changes from previous edition: Additional countries: Hungary, Italy, Lithuania, Portugal, Spain. Austria 1. Political parties Language used in data file: German Year of last election: 2013 Official party names, English 1. Sozialdemokratische Partei Österreichs (SPÖ), Social Democratic Party of Austria, 26,8% names/translation, and size in last 2. Österreichische Volkspartei (ÖVP), Austrian People's Party, 24.0% election: 3. Freiheitliche Partei Österreichs (FPÖ), Freedom Party of Austria, 20,5% 4. Die Grünen - Die Grüne Alternative (Grüne), The Greens - The Green Alternative, 12,4% 5. Kommunistische Partei Österreichs (KPÖ), Communist Party of Austria, 1,0% 6. NEOS - Das Neue Österreich und Liberales Forum, NEOS - The New Austria and Liberal Forum, 5,0% 7. Piratenpartei Österreich, Pirate Party of Austria, 0,8% 8. Team Stronach für Österreich, Team Stronach for Austria, 5,7% 9. Bündnis Zukunft Österreich (BZÖ), Alliance for the Future of Austria, 3,5% Description of political parties listed 1. The Social Democratic Party (Sozialdemokratische Partei Österreichs, or SPÖ) is a social above democratic/center-left political party that was founded in 1888 as the Social Democratic Worker's Party (Sozialdemokratische Arbeiterpartei, or SDAP), when Victor Adler managed to unite the various opposing factions. -

Ada Blair Bc

Debate: Scotland and the age of James Connolly, colonialism and radicalism after “the left” page 7 “Celtic communism” page 14 radical feminist green No 28 / WINTER 2010-11 / £2 TWO CHEE RS FOR PARLIAMENT REFERENDUM – UK VOTING SYSTEM ice of nce (1, 2, 3 etc) your cho Place in order of prefere ns to the UK Parliament. voting system for electio AV … well it’s better ALTERNATIVE VOTE 2 than the way ST FIRST PAST THE PO 3 we elect the PROPORTIONAL UK Parliament TATION 1 REPRESEN at the moment! PLUS REVIEWS AND THE LAND LAY STILL THE MODERN SNP: FROM PROTEST TO ISSN 2041-3629 POWER NEOLIBERAL SCOTLAND: CLASS 01 AND SOCIETY IN A STATELESS NATION 9 772041 362003 MAGAZINE OF SCOTLAND’S DEMOCRATIC LEFT EDITORIAL Contents I Perspectives No 28, winter 2010-11 FROM AV TO AYE WRITE! Sketches from a small world ne of the concessions the Continuing the look at books 3Eurig Scandrett Liberal Democrats got from we have a historian’s view of Othe Conservatives as part of James Robertson’s acclaimed And Two cheers for AV the agreement to form a coalition the Land Lay Still , and a review of Stuart Fairweather, Peter government was a referendum to a collection charting the SNP’s rise 5McColl and David Purdy change the voting system for to power. Westminster elections. However, Aye Write!, running from 4th to The age of radicalism the option for change will not 12th March, is Glasgow’s book after “the left” include proportional representa - festival, now in its sixth year. 7Gerry Hassan tion (PR), the Lib Dems’ preferred Democratic Left Scotland, with the method. -

No. 46, March 2016

No. 46, March 2016 Editors: Professor Dr. Horst Drescher † Lothar Görke Professor Dr. Klaus Peter Müller Ronald Walker Table of Contents Editorial 2 Comments on the Referendum, the General Election, Land Reform & Feudalist Structures - Jana Schmick, "What the Scots Wanted?" 4 - Katharina Leible, "General Election and Poll Manipulation" 8 - Andrea Schlotthauer, "High Time to Wipe Away Feudalist Structures – 10 Not Only in Scotland" Ilka Schwittlinsky, "The Scottish Universities' International Summer School – 11 Where Lovers of Literature Meet" Klaus Peter Müller, "Scottish Media: The Evolution of Public and Digital Power" 13 New Scottish Poetry: Douglas Dunn 39 (New) Media on Scotland 40 Education Scotland 58 Scottish Award Winners 61 New Publications April 2015 – February 2016 62 Book Reviews Klaus Peter Müller on Demanding Democracy: The Case for a Scottish Media 75 Klaus Peter Müller on the Common Weal Book of Ideas. 2016 – 21 83 Kate McClune on Regency in Sixteenth-Century Scotland 91 Ilka Schwittlinsky on Tartan Noir: The Definitive Guide to Scottish Crime Fiction 92 Conference Reports (ASLS, Stirling, July 2015, by Silke Stroh and Nadja Khelifa) 95 Conference Announcements 100 In Memory of Ian Bell 103 Scottish Studies Newsletter 46, March 2016 2 Editorial Dear Readers, Here is the special issue on 'Scottish Media' projected in our editorial last year. Media are so important, so hugely contested, such a relevant business market, and so significant for peo- ple's understanding of reality that this Newsletter is a bit more voluminous than usual. It also wants to challenge you in important ways: media reflect the world we live in, and this issue points out the dangers we are facing as well as the enormous relevance of your active partici- pation in making our world better, freer, more democratic. -

Remembering Scottish Communism

Gibbs, E. (2020) Remembering Scottish Communism. Scottish Labour History, 55, pp. 83-106. There may be differences between this version and the published version. You are advised to consult the publisher’s version if you wish to cite from it. http://eprints.gla.ac.uk/227600/ Deposited on: 8 January 2021 Enlighten – Research publications by members of the University of Glasgow http://eprints.gla.ac.uk Remembering Scottish Communism Ewan Gibbs Scottish Labour History vol.55 (2020) pp.83-106 Introduction The centenary of the formation of the Communist Party of Great Britain (CPGB) in 1920 provides an opportunity to assess its memory and legacy in Scotland. For seventy-one years, the CPGB’s presence within the Scottish labour movement ensured the continuity of a distinctive political culture as well as an enduring connection with the Third International’s world-historic project. The party was disproportionately concentrated on Clydeside and in the Fife coalfields, which were among its most significant strongholds across the whole of Britain. These were areas where the CPGB achieved some of its rare local and parliamentary electoral successes but also more importantly centres of enduring strength within trade unionism and community activism. Engineers and miners emerged as the party’s key public representatives in Scotland. Their appeal rested on a form of respectable working-class militancy that radiated authenticity drawn from workplace experience and standing in local communities. Abe Moffat, the President of the Scottish miners’ union between 1942 and 1961, articulated this sentiment by explaining to Paul Long in 1974 that: ‘I used to smile when I heard right-wing leaders saying that the Communists were infiltrating into the trade union: we’d been there all our lives.’1 Even within the coalfields, activists such as Moffat were part of a militant minority. -

Kilts and Tartan: Perspectives Comes Over All Scott-Ish Radical Feminist Green

Kilts and tartan: Perspectives comes over all Scott-ish radical feminist green No 41 | SUMMER 2015 | £3 Greece and the euro Policing the polis Why Scotland can flourish Women for independence The ugly side of the beautiful game SKETCHES FROM A SMALL WORLD TIM HAIGH’S SURREAL MURDER MYSTERY TREVOR ROYLE IS THE HAT ISSN 2041-3629 REVIEWS •BRIAN COX’S 07 HUMAN UNIVERSE •GRAMSCI’S EARLY WRITINGS •BIG-SCREEN FILTH 9772041362010 MAGAZINE OF SCOTLAND’S DEMOCRATIC LEFT Editorial “His name was The Labour Party, sir. Looks as though he Perspectives No 41, summer 2015 was mugged. Beaten savagely about the credibility with a blunt instrument.” – Tim Haigh on page 33 Contents 3 Sketches from a small Paying the price of no PR world Eurig Scandrett he return of a majority 2012, conveniently ignoring the Conservative government in fact that AV (as observed in the The general election 5 TMay’s general election has article “Two cheers for AV ”, and after: can Labour demonstrated, to an even greater Perspectives 28) is not a form of survive? degree than previously, the proportional representation. David Purdy dysfunctional character of the Of course, no-one expects the system used to elect the Tories to go for PR at Westminster The Greek crisis and the 8 Westminster parliament. elections when the current system crisis of the euro Consider: the Tories win an gifts them a majority of seats on Pat Devine absolute majority on the basis of just over one-third of the votes, the support of little over one third but Labour, who to their discredit Policing the polis 11 (36.8%) of voters; the SNP take 95% have supported (and similarly John Finnie of the seats in Scotland on 50% of benefitted from) first-past-the- the vote; and Ukip on 12.6% and post in the past, would do well to Wee white blossom – 14 the Greens on 3.7% take just one become advocates of some form why Scotland can seat each. -

Winter 07-08

Bhopal – Keywords: Left Smashing the cistern: 23 years on Page 3 and Right Page 13 Irvine Welsh Page 8 radical feminist green No 16 / WINTER 2007-08 / £2 THE END NO IT’S IS NIGH! NOT! MAGAZINE OF SCOTLAND’S DEMOCRATIC LEFT EDITORIAL Contents ■ Perspectives No 16, winter 2007-08 LEFT AND RIGHT, SCOTS AND WELSH Eurig Scandrett Sketches from a small s we noted in the last issue of examines the concepts of left and 3world Perspectives, 2007 was a right. In a continuing period of Ahugely symbolic year for the pessimism for many on the left, When will it all end? SNP to become the Scottish gov- this article helps to map out some Scotland and the Union ernment, 300 years after the Act of of the ground that needs to be 5by Ewen A Cameron Union. Again in this issue we gained to tilt the balance away explore the impact of 1707, with from the currently dominant and Smashing the cistern: historian Ewen A. Cameron exam- pervasive neo-liberal political dis- Irvine Welsh ining various interpretations of the course. 8by Willy Maley history of Scotland since the Returning to last year’s Scottish Union. While he makes the point parliament elections, we lamented A new view from that historians are “notoriously the decline of the smaller parties. local government bad at peering into the future,” he The Scottish Greens saw their rep- 12by Maggie Chapman nonetheless underlines the conclu- resentation cut from six to two sion of his piece by arguing that MSPs. However, the adoption of Keywords: Left “Whatever happens to the Union multiple member wards and STV and Right it is vital that we do not fabricate a in the council elections on the 13by Davie Purdy sense of denial about deep-seated same day saw the Greens take seats and long-standing Scottish enthu- in both Glasgow and Edinburgh. -

410 Participants from 37 Countries Coming from the 148 Following Parties/Movements/Trade Unions/Associations/Organisations

410 participants from 37 countries coming from the 148 following Parties/Movements/Trade Unions/Associations/Organisations: #NewRightsNow, Actrices & Acteurs des Temps Présents (Belgium), AKEL (Cyprus), Alliance for Green Socialism (UK), Alter Summit, Ander Europa (Netherlands), Another Europe Is Possible, Association "Les amis de l’Humanité", Bagong Alyansang Makabayan (Philippines), Belarusian Left Party “Fair World”, Bloco de Esquerda (Portugal), Bulgarian Left, Catalunya en Comú, Centre d'Education Populaire André Genot (CEPAG, Belgium), CliMates, Comac (Belgium), Comisiones Obreras (CCOO, Spain), Comité pour l'Abolition des Dettes illégiTiMes (CADTM), Comité pour le Développement et le Patrimoine (CDP), Communist Party of Austria (KPÖ), Communist Party of Bohemia and Moravia (KSČM), Communist Party of Finland (SKP), Communist Party of Spain (PCE), Communist Party of Ukraine (KPU), Communist Party Wallonie-Bruxelles (PCWB), Communist Youth of Finland, Confederazione Generale Italiana del Lavoro (CGIL), Convergenza Socialista (Italy), Coordinadora Latinoamericana de Solidaridad, Coordinamento Nazionale Pensionati (CONUP, Italy), Critical Political Economy Research Network, Déi Lénk (Luxembourg), Demain (Belgium), Democracy in Europe Movement 2025 (DiEM25), Democratic Left Scotland, Democratic Socialists of America (DSA), Die Linke (Germany), Ecole de Devoirs du Club Achille Chavée (Belgium), Ecologists Greens Party (Greece), EH Bildu, Elles Tournent(Belgium), Embassy of Nicaragua in Belgium, Embassy of Venezuela in Belgium, Ensemble! -

How Can We Make Change Happen? A

Issue 61 November/December 2010 scottishleftreview £2.00 how can we make change happen? A 15 scottishleftreviewIssue 61 November/December 2010 Contents The mask of reputational spin .....................16 Comment .......................................................2 Chris Holligan Much to win, much to learn ...........................5 Are we nearly there yet ...............................18 Ann Henderson Iain McWhirter Agenda 15 - reactions ...................................7 How good men do evil things .......................20 Gary Fraser Summary of Agenda 15 ...............................11 Terrorism of information .............................22 The case for privatising schools ..................14 Giannis Banias Isobel Lindsay Reviews .......................................................24 The left is not dead ......................................15 Doug Bain Doug Bain With the untimely death of Doug Bain, the left in Scotland has lost a clever, warm, witty activist who was always open to new ideas and willing to work across boundaries. He was a contributor to SLR and a regular participant at our Board meetings as a representative of Democratic Left. Doug died just at a point when his political activity and creativity was increasing again. He will be missed and remembered. On page 15 we print one of the last things Doug wrote as a tribute. comment: making change happen In the last issue of Scottish Left Review we published a programme of action for starting the transformation of Scotland into a more equitable, more sustainable and more rewarding place to live. The proposals were realistic and in many cases new – and yet predictably the mainstream media ignored it and the UK continues to drift further to the hard right. How can the left make change happen? t’s not that those of us who put the Scottish Left Review disagree with parts of what it contains or to point out the many Itogether are unrealistic people. -

Manifesto Project Dataset List of Political Parties

Manifesto Project Dataset List of Political Parties [email protected] Website: https://manifesto-project.wzb.eu/ Version 2018b from December 7, 2018 Manifesto Project Dataset - List of Political Parties Version 2018b 1 Coverage of the Dataset including Party Splits and Merges The following list documents the parties that were coded at a specific election. The list includes the name of the party or alliance in the original language and in English, the party/alliance abbreviation as well as the corresponding party identification number. In the case of an alliance, it also documents the member parties it comprises. Within the list of alliance members, parties are represented only by their id and abbreviation if they are also part of the general party list. If the composition of an alliance has changed between elections this change is reported as well. Furthermore, the list records renames of parties and alliances. It shows whether a party has split from another party or a number of parties has merged and indicates the name (and if existing the id) of this split or merger parties. In the past there have been a few cases where an alliance manifesto was coded instead of a party manifesto but without assigning the alliance a new party id. Instead, the alliance manifesto appeared under the party id of the main party within that alliance. In such cases the list displays the information for which election an alliance manifesto was coded as well as the name and members of this alliance. 2 Albania ID Covering Abbrev Parties No. Elections -

Scotland the What?

Issue 43 November/December 2007 scottishleftreview £2.00 Scotland the What? Identity and politics in 2007 dour scottishleftreviewIssue 43 November/December 2007 Contents Comment ........................................................2 Lifting the lid on PFI .....................................13 Feedback ........................................................3 Jim and Margaret Cuthbert This is the Scottish Programme ...................17 Briefing ...........................................................4 Henry McCubbin Isobel Lindsay Prison works .................................................20 Not scared to be ourselves .............................6 Gary Fraser Jimmy Reid Policies have personalities .............................8 Web Review ...................................................22 Robin McAlpine Kick Up The Tabloids.....................................23 A slogan for Scotland... .................................11 Various Comment hat is the Scottish character? People worry about dealing of the US, the long-standing bigotry of the Orange Order and Wwith lazy stereotypes, but Scottish identity matters. The in return the violent reaction of parts of the ‘Celtic-minded’ jumping-off point for this issue of the Scottish Left Review was population. The racism and suspicion of some others (including the scrapping of the ‘Best Small Country in the World’ slogan our closest neighbours…). The colonialism and the national and the ranks of people who were ready to say that it wasn’t drive for Big Profit (from the Darien Project -

Billions for Bankers, P45s for Workers. Who Says Neoliberalism's Dead?

scottishleftreview Issue 50 January/February 2009 £2.00 Billions for bankers, P45s for workers. Who says neoliberalism’s dead? scottishleftreviewIssue 50 January/February 2008 Contents Comment ........................................................2 Hidden behind hype ......................................12 Hearing what they want ..................................4 John McAllion Andy Cumbers No peace without justice...............................13 Henry Maitles Working for fairness ..........................................6 Crusade or cop-out? .....................................14 Isobel Lindsay Elle Mathuse Changing jobs .................................................8 Fifty issues on ...............................................16 Eurig Scandrett Bob Thomson Making things: not so daft. ...........................10 The vanishing lad o’pairts .............................18 Stephen Boyd Chris Holigan This, however, is debt owned by a reliable borrower. That the private debt is three times as big is the scary point – doubly so Comment when we realise that much of it isn’t even secured on anything like a real asset. We would need to spend the best part of the ou’d think nothing had happened. You’d think we were all next two years spending every single penny in the economy and Ystill living the dream. When the economy was booming we more on nothing but debt repayments to get the country square. were told the appropriate government response was to give The ‘borrow, borrow, buy some shoes’ world is passing. If the those ‘responsible’ for the boom (who happened to be big Government had a voice it ought to sound like Homer Simpson; corporations and the super-rich) anything they wanted. Tax £50 billion for the banks so they’ll start lending again. Oh no, breaks? Planning permission for pretty well anything? Giant look, they kept it all because they’re in massive debt.