MA Catalogue

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Falmouth University Access and Participation Plan 2020-21 to 2024-25

Falmouth University Access and Participation Plan 2020-21 to 2024-25 Introduction Falmouth University (Falmouth) is an anchor institution in Cornwall, fully engaged with the County’s economic, skills and enterprise agendas. The University makes a significant contribution to delivering higher skills to the county, alongside documented employment and economic benefits. Falmouth is committed to ensuring that students from all backgrounds can benefit from a Falmouth education, which facilitates their successful introduction to and participation in local and wider employment markets. Falmouth believes that it has a unique opportunity to ‘bridge’ the specialist creative disciplines to broader school subjects, as well as providing the benefits of studying at a smaller provider. Broadening this ambition locally and nationally, particular in the most deprived areas, is a priority. This is part of a commitment to sector priorities, and advocacy for the creating and performing arts as critically valuable education and career pathways for the future economy. This is enshrined in the Falmouth 2030 Strategy. As confirmed by its ‘Gold’ Teaching Excellence Framework award, Falmouth meets the highest standards for teaching quality, student retention, and graduate outcomes. While these standards provide an excellent foundation for success, Falmouth has set a vision for continuous improvement across the student lifecycle. The University’s ambitions over the coming years are to further understand and improve performance in areas that have also been highlighted as priorities at the national level, and address gaps in access and attainment for its target students. 1 Assessment of performance Falmouth University campuses are situated in Penryn and Falmouth, in Cornwall. The county is coastal, largely rural and 1 has a population of 536,000 dispersed across the region. -

Pdp4life Regional Pilot Final Report

PDP4Life – Final Report – 2 – 17-07-07 JISC DEVELOPMENT PROGRAMMES Project Document Cover Sheet PROJECT FINAL REPORT Project Project Acronym PDP4Life Project ID Project Title PDP4Life: Personal Development Planning for Lifelong Learning Start Date 01-03-05 End Date 31-04-07 Lead Institution Bournemouth University Project Director Janet Hanson [email protected] Joint Project Managers Up to 6 Dec 06: & contact details Ken Bissell [email protected] Dr Barbara Newland [email protected] After 6 Dec 06: Steve Mason (contact via Project Director) Partner Institutions Arts Institute at Bournemouth; College of St Mark & St John (Marjon); Dartington College of Arts; Open University; University of Bristol; University of Gloucestershire; University of Plymouth; Weymouth College; University College Falmouth; University Centre Yeovil Project Web URL http://www.bournemouth.ac.uk/asprojects/pdp4life/ Programme Name (and SW Regional e-learning pilot in Distributed e-learning programme number) Programme Manager Sarah Davies Document Document Title Project Final Report Reporting Period March 2005-April 2007 Author(s) & project role Janet Hanson, Project Director Steve Mason, Project Manager Date April 2007 Filename URL Access Project and JISC internal General dissemination Document History Version Date Comments 1 27 March 2006 Not published external to Bournemouth University 2 26 July 2007 Final version sent to JISC See Project Management Guidelines for information about assigning version numbers. Page 1 of 17 PDP4Life – Final -

Access Agreement 2018-19

FALMOUTH UNIVERSITY ACCESS AGREEMENT 2018-19 ACCESS AGREEMENT SUBMITTED TO THE OFFICE FOR FAIR ACCESS Submitted 25 April 2017; revised 22 June 2017 FALMOUTH UNIVERSITY ACCESS AGREEMENT 2018-19 Contents: 1. Introduction and OFFA priorities for 2018-19 page 3 2. Fees, student numbers and fee income page 5 3. Access, student success and progression measures page 7 4. Financial support page 15 5. Targets and milestones page 16 6. Monitoring and evaluation agreements page 16 7. Equality and Diversity page 16 8. Provision of information to prospective students page 17 9. Consulting with students page 17 Annex: Access Agreement Resource Plan, 2018-19 Page 2 of 18 1a. Introduction This Access Agreement sets out Falmouth University’s plans and targets to support access, student success and progression for the year 2018-19. This Agreement has been developed in the context of the University’s Strategic Plan for the period 2015 to 2020. The Strategic Plan’s key objectives reflect the University’s commitment to fair access across the student lifecycle. Our first objective is ‘to produce satisfied graduates who get great jobs’, which includes ambitious targets for student retention, student satisfaction and graduate employment. Our second objective is ‘to help grow Cornwall’, which includes a commitment to double the number of students recruited from the county from 2013-14 levels by 2020. This objective will be achieved through a sharpened focus on recruiting students from disadvantaged backgrounds. The Strategic Plan states: ‘We will work with other agencies in the region to build support systems to retain more of our creative talent for the benefit of Cornwall. -

FOI 158-19 Data-Infographic-V2.Indd

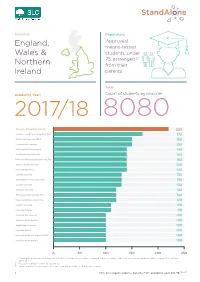

Domicile: Population: Approved, England, means-tested Wales & students, under 25, estranged [1] Northern from their Ireland parents Total: Academic Year: Count of students by provider 2017/18 8080 Manchester Metropolitan University 220 Liverpool John Moores University (LJMU) 170 De Montfort University (DMU) 150 Leeds Beckett University 150 University Of Wolverhampton 140 Nottingham Trent University 140 University Of Central Lancashire (UCLAN) 140 Sheeld Hallam University 140 University Of Salford 140 Coventry University 130 Northumbria University Newcastle 130 Teesside University 130 Middlesex University 120 Birmingham City University (BCU) 120 University Of East London (UEL) 120 Kingston University 110 University Of Derby 110 University Of Portsmouth 100 University Of Hertfordshire 100 Anglia Ruskin University 100 University Of Kent 100 University Of West Of England (UWE) 100 University Of Westminster 100 0 50 100 150 200 250 1. “Estranged” means the customer has ticked the “You are irreconcilably estranged (have no contact with) from your parents and this will not change” box on their application. 2. Results rounded to nearest 10 customers 3. Where number of customers is less than 20 at any provider this has been shown as * 1 FOI | Estranged students data by HEP, academic year 201718 [158-19] Plymouth University 90 Bangor University 40 University Of Huddersfield 90 Aberystwyth University 40 University Of Hull 90 Aston University 40 University Of Brighton 90 University Of York 40 Staordshire University 80 Bath Spa University 40 Edge Hill -

Falmouth University Finance Figures 2020

FALMOUTl-1 TI-IEFALMOUTH & EXETER UNIVERSITY STUDENTS' UNION ' SEE HOW YOUR STUDENT FEES ARE SPENT 0 5 0 04 03 02 1 FALMOUTH UNIVERSITY Increasing the transparency of Falmouth University’s Financial Information This joint publication is prepared by the University and The Students’ Union, so that all students, staff and key stakeholders understand how Falmouth University generates revenues and how that money is spent. The figures used throughout this document are those for the 2019/20 financial year with the Contents exception of the opening pages on Covid costs and the impact of the global pandemic on the University between March 2020 and March 2021. 2 The cost of COVID-19 It also shows how The Students’ Union spends the money it receives from 6 Outgoings in summary its students and the University and includes details of the joint venture, 8 Key facts Falmouth Exeter Plus. 10 Income The University and Students’ Union agreed that it was important to recognise 14 Expenditure the financial impact of Covid on the institution which have been significant 16 Student fees and have meant that fee income has been spent in responding to this event. 18 Academic departments Falmouth University is a Higher Education Corporation and has charitable 20 The Students’ Union Financial Transparency status. All surpluses generated are reinvested for the purposes of teaching and 24 Falmouth Exeter Plus research. The Students’ Union is a registered charity, number 1145405. 28 Financial support _ y The cost of COVID-19 As the UK headed towards lockdown in Spring 2020, the University made swift and Waiving accommodation rent signifcant measures to ensure the safety of staf and students, to mitigate the impact for those directly and indirectly afected by COVID -19 and to create the best possible We waived rent for all University- owned and managed accommodation from Study student experience in unprecedented circumstances. -

Why Choose Btec - Diploma Foundation Studies- Art, Design and Media Practice @ Ferndown?

Why choose Btec - Diploma Foundation Studies- Art, Design and Media Practice @ Ferndown? BA Textiles Falmouth University BA Product A Btec National Diploma Design- UAL Central St. in Foundation Studies- Martins Art, Design and Media Practice, acts as a stepping stone between A Levels and Degree courses. BSc Architecture Cardiff At Ferndown, we have University been transforming A Level students into degree ready creative practitioners since 1999. Our students regularly out perform other centres at distinction The Foundation Studies course is free for those aged 18 at the start of the course in September and all students receive a free art kit and sketchbook on joining as well as a dedicated studio space and open access to a range of facilities across the Art & Technology Faculty. BA Fine Art UCA We also run a subsidised residential visit each year to London, where over the course of four days, we try and see 15-18 exhibitions of internationally renowned Art, Craft and Design. Not only so that students are inspired and informed by what they see, but we use the visit as a starting point for a project that they can directly reference when they go for interviews. The course consists of two parts that share the same grading criteria. • Investigate • Experimentation • Evaluation and review • Realisation • Communication • Self-directed practice An Exploratory phase that consists of six projects, where experimentation and skill development are key, leading to pathway investigation, application and portfolio preparation. BA 3D Animation Bournemouth University Then onto a Confirmatory phase, where students devise their own Final Major Project, exhibit to the public and are summatively assessed as Pass, Merit or Distinction. -

Status Report for European SI/PASS/PAL-Programmes

Status report for European SI/PASS/PAL-programmes Last updated: Wednesday, 06 February 2019 Publisher: The European Centre for SI-PASS Student Affairs, Lund University Postal address: Box 117, S-22100 Lund, Sweden. Visiting address: Sölvegatan 29 B, Lund, Sweden E-mail: [email protected] Web-page: https://www.si-pass.lu.se/en/, ISBN 978-91-984120-2-4 CONTENTS FOREWORD .....................................................................................................................................5 SUMMARY .......................................................................................................................................6 STATUS OF SI/PASS/PAL PROGRAMMES IN EUROPE ...................................................8 OVERVIEW ...........................................................................................................................8 ENGLAND ..........................................................................................................................12 BOURNEMOUTH UNIVERSITY ........................................................................................................ 12 BRUNEL UNIVERSITY LONDON ...................................................................................................... 14 CANTERBURY CHRIST CHURCH UNIVERSITY ................................................................................. 16 GOLDSMITHS, UNIVERSITY OF LONDON ........................................................................................ 18 FALMOUTH UNIVERSITY ............................................................................................................... -

Academic Profile 2020-2021 TAIPEI EUROPEAN SCHOOL

42cm University Offers and Matriculations 2018-2020 TAIPEI EUROPEAN SCHOOL Universities shown in bold are those at which students have matriculated for Class of 2020. United Kingdom ・Clark University ・University of Portland Academic Profile 2020-2021 ・College of the Holy Cross ・University of Rhode Island ・Aston University ・Colorado State University-Fort Collins ・University of Rochester ・Aberystwyth University ・Columbia College Chicago ・University of San Diego ・Birmingham City University ・Columbia University ・University of San Francisco CEO ・Bournemouth University ・Cornell University ・University of Southern California CUNY John Jay College of Criminal Justice David Gatley ・Buckinghamshire New University ・ ・University of Utah ・Drew University ・Camberwell College of Arts ・University of Washington [email protected] ・Cardiff University ・Drexel University ・University of Wisconsin-Madison ・City, University of London ・Duke University Head of British Secondary ・Wake Forest University ・Coventry University ・Emerson College ・Washington State University and High School ・De Montfort University ・Emory University ・Washington University In St Louis ・Durham University ・Fordham University Sonya Papps ・Western Washington University ・Falmouth University ・George Washington University ・Whittier College [email protected] ・Glasgow School of Art ・Georgia Institute of Technology ・Hereford College of Arts ・Harvey Mudd College IB Coordinator ・Imperial College London ・Hofstra University Europe Hamish McMillan ・King's College London ・Indiana University-Bloomington -

University Placements the Following Gives an Overview of the Many Universities Tanglin Graduates Have Attended Or Received Offers from in 2018 and 2019

University Placements The following gives an overview of the many universities Tanglin graduates have attended or received offers from in 2018 and 2019. United Kingdom United States of America Abertay University Amherst College Aston University Arizona State University Student Destinations 2019 Bath Spa University Berklee College of Music Bournemouth University Boston University Central School of St Martin’s, UAL Brown University City, University of London Carleton College 1% Malaysia Coventry University Chapman University 7% De Montfort University Claremont McKenna College National Durham University Colorado State University 1% Italy Service Edinburgh Napier University Columbia College, Chicago Falmouth University Cornell University 1% Singapore Goldsmiths, University of London Duke University 1% Hong Heriot-Watt University Elon University Kong 1% Spain Imperial College London Emerson College King’s College London Fordham University 2% Holland Lancaster University Georgia Institute of Technology Liverpool John Moores University Georgia State University 4% Gap Year 64% UK London School of Economics and Hamilton College Political Science Hult International Business School, 2% Canada London South Bank University San Francisco 6% Australia Loughborough University Indiana University at Bloomington Northumbria University John Hopkins University Norwich University of the Arts Loyola Marymount University 11% USA Nottingham Trent University Michigan State University Oxford Brookes University New York University Queen’s University Belfast Northeastern -

Hangzhou International School UNIVERSITY ACCEPTANCES *University Names Highlighted Represent Class of 2020 Acceptances

Hangzhou International School UNIVERSITY ACCEPTANCES *University names highlighted represent class of 2020 acceptances United Kingdom Aberystywht University Newcastle University University of Edinburgh Birkbec University of London Oxford Brooks University University of Leicester Brunel University Portsmouth University University of Manchester Cardiff University Queen Mary University University of New South Wales Canada Durham University Roehampton University University of Nottingham Falmouth University Royal Holloway University of London University of Sheffeld Nipissing University Goldsmiths University of London University of Bath University of Southampton Simon Frasier University Imperial College London University of Birmingham University of Surrey McGill Univestity King’s College University of Bristol University of Warwick University of British Colombia London School of Economics University College London University of York University of Toronto London Metropolitan University University of East London University of Waterloo United States of America Arizona State University Miami University Seattle Central College Babson College Michigan State University Seattle Pacifc University Berklee College of Music New Jersey Institute of Technology Seton Hall University Boston College New York University St. Louis University Boston University Northeastern University St. Mary’s University Buffalo State University North Bennet Street School Stony Brook University California College of Arts Ohio State University Texas A&M University Carnegie Mellon -

Standard Document Template (Up to 5 Pages)

MA FILM & TELEVISION AT FALMOUTH WELCOME TO MA FILM & TELEVISION AT FALMOUTH. We are delighted that you have chosen Falmouth University for postgraduate study and look forward to working with you over the coming year. Your offer Please remember that if you have been made a conditional offer to study at Falmouth, your place is subject to meeting those conditions. If you need to ask us anything about your offer, get in touch with our Admissions team on 01326 213730, use Live Chat on our website or email [email protected]. First week of term Your first day of attendance will be Monday 25 September 2017, where you will meet the course team and the other members of your cohort. Your first meeting will be in Seminar Room 7, Peter Lanyon building, Penryn Campus at 2pm. This is situated on the top floor of the building. At this first meeting you will be given an overview of the course, along with a range of information regarding postgraduate study at Falmouth and all the services and amenities available to you. Your first week at Falmouth University will be an induction and orientation week in which there will be number of workshops and social activities to help you immerse yourself as quickly as possible in the culture of the department. Students will also be advised of all the systems of support that are available to you at Falmouth, along with an outline of the wider postgraduate culture. You can download a copy of the Penryn Campus map or the Falmouth Campus map from the Contact page of our website here. -

Uk University Salaries 2015-16

IN THE MONEY?: UK UNIVERSITY SALARIES 2015-16 Academics Professional and support staff Managers, directors Professor Other senior academic Other Academic total and senior officials Professional, technical and clerical Manual staff Non-academic total Female Male All Female Male All Female Male All Female Male All Female Male All Female Male All Female Male All Female Male All University of Aberdeen £73,143 £80,757 £79,156 .. £114,461 £102,490 £41,830 £45,690 £44,018 £45,217 £54,483 £50,824 £58,403 £59,310 £58,896 £30,683 £35,583 £32,423 £20,122 £22,932 £22,384 £30,991 £32,832 £31,801 Abertay University .. £63,717 £63,764 .. £66,617 £66,491 £40,197 £42,258 £41,419 £42,562 £47,158 £45,441 .. £75,041 £68,896 £28,985 £31,879 £30,029 .. £23,379 £22,900 £30,084 £32,874 £31,387 Aberystwyth University £67,667 £72,679 £71,989 .. .. .. £41,757 £43,249 £42,689 £43,994 £49,324 £47,525 £46,820 £49,492 £48,423 £28,502 £30,153 £29,224 £18,075 £18,782 £18,675 £29,070 £27,845 £28,400 Anglia Ruskin University £66,238 £65,406 £65,723 £77,006 £96,030 £87,383 £43,323 £43,394 £43,357 £46,384 £49,223 £47,771 £55,661 £66,201 £60,839 £32,075 £35,007 £33,163 £22,979 £24,293 £23,787 £32,859 £35,786 £34,063 University of the Arts London £71,562 £68,132 £70,071 £78,617 £95,898 £86,768 £49,686 £48,278 £48,892 £54,437 £53,243 £53,782 £64,498 £65,740 £65,170 £35,436 £38,509 £36,596 £26,479 £26,416 £26,425 £36,752 £38,560 £37,532 Arts University Bournemouth .