Inspection Examination of the Ureter and Biopsy Procedure Specific

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Study Guide Medical Terminology by Thea Liza Batan About the Author

Study Guide Medical Terminology By Thea Liza Batan About the Author Thea Liza Batan earned a Master of Science in Nursing Administration in 2007 from Xavier University in Cincinnati, Ohio. She has worked as a staff nurse, nurse instructor, and level department head. She currently works as a simulation coordinator and a free- lance writer specializing in nursing and healthcare. All terms mentioned in this text that are known to be trademarks or service marks have been appropriately capitalized. Use of a term in this text shouldn’t be regarded as affecting the validity of any trademark or service mark. Copyright © 2017 by Penn Foster, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of the material protected by this copyright may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the copyright owner. Requests for permission to make copies of any part of the work should be mailed to Copyright Permissions, Penn Foster, 925 Oak Street, Scranton, Pennsylvania 18515. Printed in the United States of America CONTENTS INSTRUCTIONS 1 READING ASSIGNMENTS 3 LESSON 1: THE FUNDAMENTALS OF MEDICAL TERMINOLOGY 5 LESSON 2: DIAGNOSIS, INTERVENTION, AND HUMAN BODY TERMS 28 LESSON 3: MUSCULOSKELETAL, CIRCULATORY, AND RESPIRATORY SYSTEM TERMS 44 LESSON 4: DIGESTIVE, URINARY, AND REPRODUCTIVE SYSTEM TERMS 69 LESSON 5: INTEGUMENTARY, NERVOUS, AND ENDOCRINE S YSTEM TERMS 96 SELF-CHECK ANSWERS 134 © PENN FOSTER, INC. 2017 MEDICAL TERMINOLOGY PAGE III Contents INSTRUCTIONS INTRODUCTION Welcome to your course on medical terminology. You’re taking this course because you’re most likely interested in pursuing a health and science career, which entails proficiencyincommunicatingwithhealthcareprofessionalssuchasphysicians,nurses, or dentists. -

Oncology 101 Dictionary

ONCOLOGY 101 DICTIONARY ACUTE: Symptoms or signs that begin and worsen quickly; not chronic. Example: James experienced acute vomiting after receiving his cancer treatments. ADENOCARCINOMA: Cancer that begins in glandular (secretory) cells. Glandular cells are found in tissue that lines certain internal organs and makes and releases substances in the body, such as mucus, digestive juices, or other fluids. Most cancers of the breast, pancreas, lung, prostate, and colon are adenocarcinomas. Example: The vast majority of rectal cancers are adenocarcinomas. ADENOMA: A tumor that is not cancer. It starts in gland-like cells of the epithelial tissue (thin layer of tissue that covers organs, glands, and other structures within the body). Example: Liver adenomas are rare but can be a cause of abdominal pain. ADJUVANT: Additional cancer treatment given after the primary treatment to lower the risk that the cancer will come back. Adjuvant therapy may include chemotherapy, radiation therapy, hormone therapy, targeted therapy, or biological therapy. Example: The decision to use adjuvant therapy often depends on cancer staging at diagnosis and risk factors of recurrence. BENIGN: Not cancerous. Benign tumors may grow larger but do not spread to other parts of the body. Also called nonmalignant. Example: Mary was relieved when her doctor said the mole on her skin was benign and did not require any further intervention. BIOMARKER TESTING: A group of tests that may be ordered to look for genetic alterations for which there are specific therapies available. The test results may identify certain cancer cells that can be treated with targeted therapies. May also be referred to as genetic testing, molecular testing, molecular profiling, or mutation testing. -

Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease (GERD)

Guidelines for Clinical Care Quality Department Ambulatory GERD Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease (GERD) Guideline Team Team Leader Patient population: Adults Joel J Heidelbaugh, MD Objective: To implement a cost-effective and evidence-based strategy for the diagnosis and Family Medicine treatment of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). Team Members Key Points: R Van Harrison, PhD Diagnosis Learning Health Sciences Mark A McQuillan, MD History. If classic symptoms of heartburn and acid regurgitation dominate a patient’s history, then General Medicine they can help establish the diagnosis of GERD with sufficiently high specificity, although sensitivity Timothy T Nostrant, MD remains low compared to 24-hour pH monitoring. The presence of atypical symptoms (Table 1), Gastroenterology although common, cannot sufficiently support the clinical diagnosis of GERD [B*]. Testing. No gold standard exists for the diagnosis of GERD [A*]. Although 24-hour pH monitoring Initial Release is accepted as the standard with a sensitivity of 85% and specificity of 95%, false positives and false March 2002 negatives still exist [II B*]. Endoscopy lacks sensitivity in determining pathologic reflux but can Most Recent Major Update identify complications (eg, strictures, erosive esophagitis, Barrett’s esophagus) [I A]. Barium May 2012 radiography has limited usefulness in the diagnosis of GERD and is not recommended [III B*]. Content Reviewed Therapeutic trial. An empiric trial of anti-secretory therapy can identify patients with GERD who March 2018 lack alarm or warning symptoms (Table 2) [I A*] and may be helpful in the evaluation of those with atypical manifestations of GERD, specifically non-cardiac chest pain [II B*]. Treatment Ambulatory Clinical Lifestyle modifications. -

Biopsy and Cytology

BIOPSY AND CYTOLOGY Biopsy • Definition • Biopsy is the removal of a sample of living tissue for laboratory examination. • Rationale • It is a dentist’s obligation to make a diagnosis, or see that a diagnosis is made, of any pathological lesion in the mouth. • Some lesions can be diagnosed clinically, and biopsy is not required e.g. recurrent aphthous ulceration, Herpes simplex lesions. • Many lesions cannot be positively diagnosed clinically and should be biopsied – or in some cases smeared for cytopathologic examination. • Pitfalls of relying on a strictly clinical diagnosis are numerous: • A loose tooth may be due to a malignancy, not to advance periodontal disease. • What appears to be a dentigerous cyst clinically e.g. may be an odontogenic tumor. • Harmless looking white patches may be malignant or premalignant. Red patches are even more important. • It has been said that “any tissue which has been removed surgically is worth examining microscopically” • Yet dentists in general do not follow this rule. • However, there are some tissues e.g. gingivectomies, where every specimen need not be submitted. • While cancer is one disease in which biopsy is important, there are many other lesions in which this procedure is useful. • It is a sensitive diagnostic tool. CDE (Oral Pathology and Oral Medicine) 1 BIOPSY AND CYTOLOGY • Methods of Biopsy • Excisional – entire lesion is removed, along with a margin of normal tissue. • Incisional – representative portion of the lesion is removed, along with a margin of normal tissue. • Electrocautery – tends to damage tissue and make interpretation difficult. • Punch • Needle and aspiration • Curettage – intraosseous • Exfoliative cytology. • The Oral Biopsy – Avoidable Pitfalls. -

Biopsy Features in Inflammatory Bowel Disease Gut: First Published As 10.1136/Gut.35.7.961 on 1 July 1994

Gut 1994; 35: 961-968 961 Observer variation and discriminatory value of biopsy features in inflammatory bowel disease Gut: first published as 10.1136/gut.35.7.961 on 1 July 1994. Downloaded from A Theodossi, D J Spiegelhalter, J Jass, J Firth, M Dixon, M Leader, D A Levison, R Lindley, I Filipe, A Price, N A Shepherd, S Thomas, H Thompson Abstract macroscopic and biopsy material taken from If skilled histopathologists disagree over patients with inflammatory bowel disease. the same biopsy specimen, at least one They reported the percentage agreement, but must have an incorrect interpretation. did not take into account the proportion of Thus, disagreement is associated with, observed agreement due to chance alone. although not the cause of, diagnostic Surawicz and Belic6 and Allison et al 7 con- error. The present study aimed to sidered the value of features in discriminating determine the magnitude of variation acute self limited colitis from idiopathic among 10 observers with a special interest inflammatory bowel disease, and reported both in gastrointestinal histopathology. They definitions and simple percentage agreement independently interpreted the same on selected features. biopsy specimens for morphological We believe that histopathology provides an features which may discriminate between important contribution to the diagnosis of patients with Crohn's disease and ulcera- inflammatory bowel disease. The aim of the tive colitis and normal subjects. Thirty of present study therefore was to determine the 41 features had agreement measures reliability of the information obtained from significantly better than expected by colorectal mucosal biopsy specimens by chance (p<005). The range of agreement assessing the magnitude of variation among 10 in the 45 observer pairs over the final histopathologists with a special interest in diagnosis was 65-76%. -

AASLD Position Paper : Liver Biopsy

AASLD POSITION PAPER Liver Biopsy Don C. Rockey,1 Stephen H. Caldwell,2 Zachary D. Goodman,3 Rendon C. Nelson,4 and Alastair D. Smith5 This position paper has been approved by the AASLD and College of Cardiology and the American Heart Associa- represents the position of the association. tion Practice Guidelines3).4 Introduction Preamble Histological assessment of the liver, and thus, liver bi- These recommendations provide a data-supported ap- opsy, is a cornerstone in the evaluation and management proach. They are based on the following: (1) formal re- of patients with liver disease and has long been considered view and analysis of the recently published world to be an integral component of the clinician’s diagnostic literature on the topic; (2) American College of Physi- armamentarium. Although sensitive and relatively accu- cians Manual for Assessing Health Practices and De- rate blood tests used to detect and diagnose liver disease signing Practice Guidelines1; (3) guideline policies, have now become widely available, it is likely that liver including the AASLD Policy on the Development and biopsy will remain a valuable diagnostic tool. Although Use of Practice Guidelines and the American Gastro- histological evaluation of the liver has become important enterological Association Policy Statement on Guide- in assessing prognosis and in tailoring treatment, nonin- lines2; and (4) the experience of the authors in the vasive techniques (i.e., imaging, blood tests) may replace specified topic. use of liver histology in this setting, particularly with re- Intended for use by physicians, these recommenda- gard to assessment of the severity of liver fibrosis.5,6 Sev- tions suggest preferred approaches to the diagnostic, ther- eral techniques may be used to obtain liver tissue; a table apeutic, and preventive aspects of care. -

Needle Biopsy and Radical Prostatectomy Specimens David J Grignon

Modern Pathology (2018) 31, S96–S109 S96 © 2018 USCAP, Inc All rights reserved 0893-3952/18 $32.00 Prostate cancer reporting and staging: needle biopsy and radical prostatectomy specimens David J Grignon Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, Indiana University School of Medicine, IUH Pathology Laboratory, Indianapolis, IN, USA Prostatic adenocarcinoma remains the most common cancer affecting men. A substantial majority of patients have the diagnosis made on thin needle biopsies, most often in the absence of a palpable abnormality. Treatment choices ranging from surveillance to radical prostatectomy or radiation therapy are largely driven by the pathologic findings in the biopsy specimen. The first part of this review focuses on important morphologic parameters in needle biopsy specimens that are not covered in the accompanying articles. This includes tumor quantification as well as other parameters such a extraprostatic extension, seminal vesicle invasion, perineural invasion, and lymphovascular invasion. For those men who undergo radical prostatectomy, pathologic stage and other parameters are critical in prognostication and in determining the appropriateness of adjuvant therapy. Staging parameters, including extraprostatic extension, seminal vesicle invasion, and lymph node status are discussed here. Surgical margin status is also an important parameter and definitions and reporting of this feature are detailed. Throughout the article the current reporting guidelines published by the College of American Pathologists and the International Collaboration on Cancer Reporting are highlighted. Modern Pathology (2018) 31, S96–S109; doi:10.1038/modpathol.2017.167 The morphologic aspects of prostatic adenocarcinoma hormonal therapy.4,5 For needle biopsy specimens the have a critical role in the management and prognos- data described below are largely based on standard tication of patients with prostatic adenocarcinoma. -

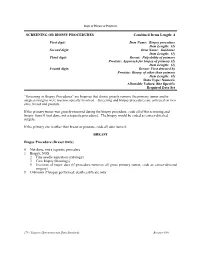

SCREENING OR BIOPSY PROCEDURES Combined Items Length: 4 First Digit: Item Name: Biopsy Procedure Item Length: (1) Second Digit

Stage of Disease at Diagnosis SCREENING OR BIOPSY PROCEDURES Combined Items Length: 4 First digit: Item Name: Biopsy procedure Item Length: (1) Second digit: Item Name: Guidance Item Length: (1) Third digit: Breast: Palpability of primary Prostate: Approach for biopsy of primary (1) Item Length: (1) Fourth digit: Breast: First detected by Prostate: Biopsy of other than primary Item Length: (1) Data Type: Numeric Allowable Values: Site Specific Required Data Set “Screening or Biopsy Procedures” are biopsies that do not grossly remove the primary tumor and/or surgical margins were macroscopically involved. Screening and biopsy procedures are collected on two sites, breast and prostate. If the primary tumor was grossly removed during the biopsy procedure, code all of the screening and biopsy items 0 (not done, not a separate procedure). The biopsy would be coded as cancer-directed surgery. If the primary site is other than breast or prostate, code all data items 0. BREAST Biopsy Procedure (Breast Only) 0 Not done, not a separate procedure 1 Biopsy, NOS 2 Fine needle aspiration (cytology) 3 Core biopsy (histology) 5 Excision of major duct (if procedure removes all gross primary tumor, code as cancer-directed surgery) 9 Unknown if biopsy performed; death certificate only 178 / Registry Operations and Data Standards Revised 8/00 CODE DEFINITION (BIOPSY PROCEDURE) 0 No screening or biopsy procedures were done. Biopsy was performed, but was a part of first course surgery (e.g, excisional biopsy). Not a breast or prostate primary 1 A biopsy was done, but the type is unknown. 2 A fine needle aspiration was done and the results were interpreted by cytology. -

Icd-9-Cm (2010)

ICD-9-CM (2010) PROCEDURE CODE LONG DESCRIPTION SHORT DESCRIPTION 0001 Therapeutic ultrasound of vessels of head and neck Ther ult head & neck ves 0002 Therapeutic ultrasound of heart Ther ultrasound of heart 0003 Therapeutic ultrasound of peripheral vascular vessels Ther ult peripheral ves 0009 Other therapeutic ultrasound Other therapeutic ultsnd 0010 Implantation of chemotherapeutic agent Implant chemothera agent 0011 Infusion of drotrecogin alfa (activated) Infus drotrecogin alfa 0012 Administration of inhaled nitric oxide Adm inhal nitric oxide 0013 Injection or infusion of nesiritide Inject/infus nesiritide 0014 Injection or infusion of oxazolidinone class of antibiotics Injection oxazolidinone 0015 High-dose infusion interleukin-2 [IL-2] High-dose infusion IL-2 0016 Pressurized treatment of venous bypass graft [conduit] with pharmaceutical substance Pressurized treat graft 0017 Infusion of vasopressor agent Infusion of vasopressor 0018 Infusion of immunosuppressive antibody therapy Infus immunosup antibody 0019 Disruption of blood brain barrier via infusion [BBBD] BBBD via infusion 0021 Intravascular imaging of extracranial cerebral vessels IVUS extracran cereb ves 0022 Intravascular imaging of intrathoracic vessels IVUS intrathoracic ves 0023 Intravascular imaging of peripheral vessels IVUS peripheral vessels 0024 Intravascular imaging of coronary vessels IVUS coronary vessels 0025 Intravascular imaging of renal vessels IVUS renal vessels 0028 Intravascular imaging, other specified vessel(s) Intravascul imaging NEC 0029 Intravascular -

Lung Cancer Biopsies

UNDERSTANDING LUNG CANCER BIOPSIES 1-800-298-2436 LungCancerAlliance.org 1 1 CONTENTS What is a Biopsy? ..............................................................................................................3 Non-Surgical Biopsies .....................................................................................................4 Surgical Biopsies ...............................................................................................................6 Risks of Having a Biopsy .................................................................................................7 Questions to Ask ...............................................................................................................8 For More Information ......................................................................................................9 About Lung Cancer Alliance ...................................................................................... 10 2 WHAT IS A BIOPSY? WHAT DOES A BIOPSY TELL US? A biopsy is a procedure to determine if a suspicious area is cancer. In a biopsy, tissue or fluid is removed from the body and examined under a microscope by a doctor called a pathologist. If the biopsy indicates there is cancer present, it also identifies the type of cancer. If it is lung cancer, the biopsy should show the type of lung cancer, either non- small cell or small cell. There are a number of ways that tissue or fluid can be removed for biopsy. The type of procedure is determined by what is being studied, where it is located in -

Weekend RUSH Biopsy Scanning Protocol

01/2020 Weekend RUSH Biopsy Protocol Background: While many cases are labelled “RUSH” in Beaker, not all are clinically rush cases, and may have just received that label due to protocols (ie most biopsy specimens). These protocols help ensure that cases are processed as swiftly, efficiently and accurately as possible by all anatomic pathology staff who encounter the case. During the week, in most cases this distinction is not as significant. However, for cases accessioned on Fridays, it is important to make the distinction between cases that are truly rush and those that are not. True rush cases need to be looked at by a pathologist the following day (Saturday), and a preliminary result may need to be communicated to the clinicians if indicated. Cases that are not truly rush do not need to be looked at over the weekend. True rush cases can be scanned by histology Saturday morning, and available for digital review. How do I tell if a case is a true rush? Is the case flagged as rush? Check the protocol assigned to the case. o Some protocols are commonly associated with a true rush status (ie: Kidney, Biopsy) o Some protocols are rarely associated with a true rush status: (ie: Breast, Core Biopsy) Check the clinical context. o In broad terms, some clinical questions are a rush and some are not, even if the tissue that was collected may seem like it (i.e. a biopsy specimen) o Examples: . Tumor diagnoses generally are not a rush I.e.: biopsies of the breast, cervix, liver for tumor, lymph nodes, etc One exception could be if the patient in the hospital, requiring diagnosis for immediate treatment. -

ICD-9-CM Procedure Version 23

Procedure Code Set General Equivalence Mappings ICD-10-PCS to ICD-9-CM and ICD-9-CM to ICD-10-PCS 2008 Version Documentation and User’s Guide Preface Purpose and Audience This document accompanies the 2008 update of the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Studies (CMS) public domain code reference mappings of the ICD-10 Procedure Code System (ICD-10- PCS) and the International Classification of Diseases 9th Revision (ICD-9-CM) Volume 3. The purpose of this document is to give readers the information they need to understand the structure and relationships contained in the mappings so they can use the information correctly. The intended audience includes but is not limited to professionals working in health information, medical research and informatics. General interest readers may find section 1 useful. Those who may benefit from the material in both sections 1 and 2 include clinical and health information professionals who plan to directly use the mappings in their work. Software engineers and IT professionals interested in the details of the file format will find this information in Appendix A. Document Overview For readability, ICD-9-CM is abbreviated “I-9,” and ICD-10-PCS is abbreviated “PCS.” The network of relationships between the two code sets described herein is named the General Equivalence Mappings (GEMs). • Section 1 is a general interest discussion of mapping as it pertains to the GEMs. It includes a discussion of the difficulties inherent in linking two coding systems of different design and structure. The specific conventions and terms employed in the GEMs are discussed in more detail.