Investigating the Gentrification of the Fountain Square

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Culturaldistrict 2012 Layout 1

INDIANA INDIANA UNIVERSITY PUBLIC POLICY INSTITUTE PUBLIC POLICY RESEARCH FOR INDIANA JULY 2012 Indianapolis Cultural Trail sees thousands of users during Super Bowl The Indianapolis Cultural Trail: A Legacy of Gene and Marilyn data for the Indy Greenways trail network. PPI began counting Glick (Cultural Trail) started with a vision of an urban trail net- trail traffic at four locations along the Monon Trail in February work that would highlight the many culturally rich neighbor- 2001, and is currently monitoring a network of 19 locations on hoods and promote the walkability of the city of Indianapolis. seven trails in Indianapolis including the Monon, Fall Creek, Based upon the success of the Monon Trail and the Indy Canal Towpath, Eagle Creek, White River, Pennsy, and Pleasant Greenways system, the Cultural Trail was designed to connect the Run trails. There were two primary goals for setting up counters five Indianapolis cultural districts (the Wholesale District, Indiana along the Cultural Trail: first, to show the benefit and potential Avenue, the Canal & White River State Park, Fountain Square, uses of trail data, and second, to analyze the impact of a large and Mass Ave) and Broad Ripple Village. While each cultural dis- downtown event like the Super Bowl. trict exhibits unique characteristics and offers much to visitors This report presents data collected at two points along the and residents alike, connecting the districts offers greater poten- Cultural Trail (Alabama Street and Glick Peace Walk) during a tial to leverage the cities’ assets and promote its walkability. The three-week period around the 2012 Super Bowl festivities. -

Assessment of the Impact of the Indianapolis Cultural Trail: a Legacy of Gene and Marilyn Glick

Assessment of the Impact of the Indianapolis Cultural Trail: A Legacy of Gene and Marilyn Glick 334 N. Senate Avenue, Suite 300 Indianapolis, IN 46204 Assessment of the Impact of the Indianapolis Cultural Trail: A Legacy of Gene and Marilyn Glick March 2015 15-C02 Authors List of Tables .......................................................................................................................... iii Jessica Majors List of Maps ............................................................................................................................ iii Graduate Assistant List of Figures ......................................................................................................................... iv IU Public Policy Institute Executive Summary ................................................................................................................ 1 Key findings ....................................................................................................................... 1 Sue Burow An eye on the future .......................................................................................................... 2 Senior Policy Analyst Introduction ............................................................................................................................. 3 IU Public Policy Institute Background ....................................................................................................................... 3 Measuring the Use of the Indianapolis Cultural Trail: A Legacy of Gene -

COMPLETE Board Packet for September 27, 2018 Meeting

Board Report September 27, 2018 www.IndyGo.net 317.635.3344 INDIANAPOLIS PUBLIC TRANSPORTATION CORPORATION –INDYGO BOARD OF DIRECTORS’ PUBLIC MEETING AGENDA – SEPTEMBER 27, 2018 New Business RECOGNITIONS ACTION ITEMS A – 1 Consideration of Approval of Minutes from Board Meeting held on August 23, 2018 – Danny Crenshaw A – 2 Consideration and Approval of Procurement of Two (2) Non-Revenue Para transit Supervisor Support Vehicles from State QPA – Vicki Learn A—3 Consideration and Approval of two (2) Non-revenue Fully Electric Support Vehicles – Vicki Learn A – 4 Approval of Administrative Office Construction Bid – LaTeeka Washington A – 5 Consideration and Approval of Bus Shelter Procurement – Annette Darrow A – 6 Consideration and Approval of Tire Lease Contract – Roscoe Brown A – 7 Task Order for Red Line Traffic Signal Timing Development – Sri Venugopalan A – 8 Approval of Red Line Construction Change Orders (FA Wilhelm & Rieth Riley) – Sri Venugopalan A – 9 Approval of Red Line Design Amendment (CDM Smith) – Sri Venugopalan Old Business INFORMATION ITEMS I – 1 Consideration of Receipt of Mobility Advisory Committee Report – Ryan Malone, Chair I – 2 Consideration of Receipt of the Finance Report for August 2018 – Nancy Manley I – 3 2017 Corporation Audit Report – Nancy Manley I – 4 Presentation on Service Standards – Bryan Luellen I – 5 CEO Update – Mike Terry Department Reports in Board Packet: R – 1 Public Affairs & Communications Report for August 2018 – Bryan Luellen R – 2 Planning & Capital Projects Report for August 2018 –Justin Stuehrenberg R – 3 Operations Report for August 2018 – Roscoe Brown R – 4 Human Resources Report for August 2018 – Phalease Crichlow Executive Session Prior to Board Meeting [Per IC 5-14- 1.5.6.1(b) (2) (A) and (B) & IC 5-14-1.5.6.1 (b) (9)] __________________________________________________________________________________________ Our next Board Meeting will be Thursday, October 25, 2018 IndyGo Agenda September 27, 2018 Item No. -

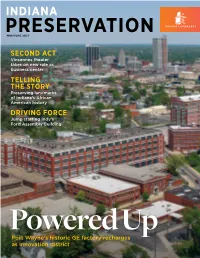

Second Act Telling the Story Driving Force

MAY/JUNE 2021 SECOND ACT Vincennes theater takes on new role as business center TELLING THE STORY Preserving landmarks of Indiana’s African American history DRIVING FORCE Jump starting Indy’s Ford Assembly Building Powered Up Fort Wayne’s historic GE factory recharges as innovation district FROM THE PRESIDENT STARTERS BOARD OF DIRECTORS OFFICERS Olon F. Dotson Muncie Hon. Randall T. Shepard Honorary Chair Melissa Glaze Roanoke Sara Edgerton Chair Tracy Haddad What’s Columbus Parker Beauchamp Rightful Recognition Past Chair David A. Haist Wabash Doris Anne Sadler in a Name? JUNETEENTH IS GAINING RIGHTFUL recognition as a day of Vice Chair Emily J. Harrison Attica Marsh Davis IN CHOOSING THE NAME national celebration and reflection. On June 19, 1865—two months President Sarah L. Lechleiter Indianapolis Electric Works—the mixed- after the surrender of Confederate forces at Appomattox—U.S. Hilary Barnes Secretary/Assistant Treasurer Shelby Moravec use innovation district being LaPorte Major General Gordon Granger arrived with roughly 2,000 Union Thomas H. Engle Assistant Secretary Ray Ontko developed on the site of the troops on Galveston Island with word that the Civil War was over Richmond Brett D. McKamey former General Electric (GE) and enslaved people were free. On that date, General Granger Treasurer Martin E. Rahe Cincinnati, OH Judy A. O’Bannon campus in Fort Wayne— NOT SO COMMON issued General Order No. 3, which stated: Secretary Emerita James W. Renne Newburgh development group RTM s malls began drawing shoppers to the suburbs in the 1960s, DIRECTORS David A. Resnick, CPA Ventures took inspiration leaders in Columbus, Indiana, sought ways to keep business The people of Texas are informed that, in accordance with a Carmel Sarah Evans Barker downtown. -

Task 4/6 Report: Programming & Destinations

Tasks Four/Six: Destinations and Programming In these tasks, the team developed an understanding for destinations, events, programming, and gathering places along the White River. The team evaluated existing and potential destinations in both Hamilton and Marion Counties, and recommended new catalyst sites and destinations along the River. The following pages detail our process and understanding of important destinations for enhanced or new protection, preservation, programming and activation for the river. Core Team DEPARTMENT OF METROPOLITAN DEVELOPMENT HAMILTON COUNTY TOURISM, INC. VISIT INDY RECONNECTING TO OUR WATERWAYS Project Team AGENCY LANDSCAPE + PLANNING APPLIED ECOLOGICAL SERVICES, INC. CHRISTOPHER B. BURKE ENGINEERING ENGAGING SOLUTIONS FINELINE GRAPHICS HERITAGE STRATEGIES HR&A ADVISORS, INC. LANDSTORY LAND COLLECTIVE PORCH LIGHT PROJECT PHOTO DOCS RATIO ARCHITECTS SHREWSBERRY TASK FOUR/SIX: DESTINATIONS AND PROGRAMMING Table of Contents Destinations 4 Programming 18 Strawtown Koteewi 22 Downtown Noblesville 26 Allisonville Stretch 30 Oliver’s Crossing 34 Broad Ripple Village 38 Downtown Indianapolis 42 Southwestway Park 46 Historic Review 50 4 Destinations Opportunities to invest in catalytic projects exist all along the 58-mile stretch of the White River. Working together with the client team and the public, the vision plan identified twenty-seven opportunity sites for preservation, activation, enhancements, or protection. The sites identified on the map at right include existing catalysts, places that exist but could be enhanced, and opportunities for future catalysts. All of these are places along the river where a variety of experiences can be created or expanded. This long list of destinations or opportunity sites is organized by the five discovery themes. Certain locations showed clear overlap among multiple themes and enabled the plan to filter through the long list to identify seven final sites to explore as plan ‘focus areas’ or ‘anchors’. -

All Indiana State Historical Markers As of 2/9/2015 Contact Indiana Historical Bureau, 317-232-2535, [email protected] with Questions

All Indiana State Historical Markers as of 2/9/2015 Contact Indiana Historical Bureau, 317-232-2535, [email protected] with questions. Physical Marker County Title Directions Latitude Longitude Status as of # 2/9/2015 0.1 mile north of SR 101 and US 01.1977.1 Adams The Wayne Trace 224, 6640 N SR 101, west side of 40.843081 -84.862266 Standing. road, 3 miles east of Decatur Geneva Downtown Line and High Streets, Geneva. 01.2006.1 Adams 40.59203 -84.958189 Standing. Historic District (Adams County, Indiana) SE corner of Center & Huron Streets 02.1963.1 Allen Camp Allen 1861-64 at playground entrance, Fort Wayne. 41.093695 -85.070633 Standing. (Allen County, Indiana) 0.3 mile east of US 33 on Carroll Site of Hardin’s Road near Madden Road across from 02.1966.1 Allen 39.884356 -84.888525 Down. Defeat church and cemetery, NW of Fort Wayne Home of Philo T. St. Joseph & E. State Boulevards, 02.1992.1 Allen 41.096197 -85.130014 Standing. Farnsworth Fort Wayne. (Allen County, Indiana) 1716 West Main Street at Growth Wabash and Erie 02.1992.2 Allen Avenue, NE corner, Fort Wayne. 41.078572 -85.164062 Standing. Canal Groundbreaking (Allen County, Indiana) 02.19??.? Allen Sites of Fort Wayne Original location unknown. Down. Guldin Park, Van Buren Street Bridge, SW corner, and St. Marys 02.2000.1 Allen Fort Miamis 41.07865 -85.16508333 Standing. River boat ramp at Michaels Avenue, Fort Wayne. (Allen County, Indiana) US 24 just beyond east interchange 02.2003.1 Allen Gronauer Lock No. -

Downtown Indianapolis Restaurant Sites

Downtown Indianapolis Restaurant Sites Maxine's Chicken and Waffles 132 N East St, Indianapolis, IN 46204 Barcelona Tapas 201 N Delaware St, Indianapolis, IN 46204 Saffron Cafe 621 Fort Wayne Avenue, Indianapolis, IN 46204 Downtown Olly's 822 N Illinois St, Indianapolis, IN 46204 Bourbon Street Restaurant & Distillery 361 N Indiana Ave, Indianapolis, IN 46204 Iaria's Italian Restaurant 317 S College Ave, Indianapolis, IN 46202 South of Chicago Pizza & Beef 619 Virginia Avenue, Indianapolis, IN 46203 Bluebeard 653 Virginia Ave, Indianapolis, IN 46203 Acapulco Joe's Mexican Food 365 N Illinois St, Indianapolis, IN 46204 Tortas Guicho Dominguez y el Cubanito 641 Virginia Avenue, Indianapolis, IN 46203 City Cafe 443 N Pennsylvania St, Indianapolis, IN 46204 India Garden 207 N Delaware St, Indianapolis, IN 46204 Le Peep 301 N Illinois St, Indianapolis, IN 46204 Milano Inn 231 S College Ave, Indianapolis, IN 46202 Elbow Room Pub & Deli 605 N Pennsylvania St, Indianapolis, IN 46204 Ralph's Great Divide 743 E New York St, Indianapolis, IN 46202 English Ivy's 944 N Alabama St, Indianapolis, IN 46202 Hong Kong 1524 N Illinois St, Indianapolis, IN 46202 Milktooth 534 Virginia Ave, Indianapolis, IN 46203 Bangkok Restaurant & Jazz Bar 225 East Ohio St, Indianapolis, IN 46204 Datsa Pizza 907 N Pennsylvania St, Indianapolis, IN 46204 Plow and Anchor 43 9th St, Indianapolis, IN 46204 Calvin Fletcher's Coffee Company 647 Virginia Ave, Indianapolis, IN 46203 Sahm's Tavern 433 N. Capitol, Indianapolis, IN 46204 Bearcats Restaurant 1055 N Senate Ave, Indianapolis, -

White River State Park Development Commission Agency Overview

WHITE RIVER STATE PARK DEVELOPMENT COMMISSION AGENCY OVERVIEW In 1979, the Indiana General Assembly created the White River State Park Development Commission (WRSPDC) to develop and operate White River State Park (WRSP). Enhancing the health and well-being of visitors is the mission of the Park, providing cultural, entertainment, and recreational benefits to millions of Indiana citizens and visitors from all over the world. Mission Statement 1. To develop on the banks of the White River in the State’s Capitol city an urban park of unique character that: Captures the history and traditions that have marked Indiana’s growth and development; Provides an aesthetic gathering place that celebrates the State’s natural endowments; Creates new recreational, cultural, and educational opportunities for the general public; and Contributes to the economic well-being of the State. 2. To provide continuity in the development process for the Park and to establish an environment that can attract investment and commitment. Park Attractions and Tenants The Park owns over 250-acres of property on the east and west sides of the White River in downtown Indianapolis. The list of Park attractions, tenants and features includes: Open Areas Celebration Plaza and Amphitheater Children’s Maze Historic Central Canal (West Street to White River) Historic Military Park Historic Old Washington Street Pedestrian Bridge Historic Pumphouse Amphitheater Historic Pumphouse Island Indiana State Museum Lawn Terraced Gardens The Governor’s Lawn The Old National Road (Historic U.S. 40) The Oval White River Promenade and Amphitheater Tenants Eiteljorg Museum of American Indians & Western Art IMAX ® Theater (inside Indiana State Museum – Park operated) Indiana State Museum Indianapolis Zoo & White River Gardens Victory Field (Indianapolis Indians Baseball) NCAA ® Hall of Champions NCAA ® Headquarters National Federation of State High School Associations National Institute for Fitness & Sport (on Indiana University owned land) Other Attractions/Features Congressional Medal of Honor Memorial Dr. -

NEIGHBORHOODS MAP a B C D E F G 18Th St

NEIGHBORHOODS MAP A B C D E F G 18th St. Fall Herron-Morton Place Creek 17th St. 18th St. Place Aqueduct St. 17th St. 17th St. New Jersey St. Central Ave. 17th St. 16th St. Pl. Senate Blvd. Pennsylvania St. 16th St. 16th St. College Ave. Park Ave. 16 Tech 15th St. Delaware St. 15th St. Alabama St. 1 1 14th St. Illinois St. 14th St. Capitol Ave. Milburn St. Milburn Old Northside Montcalm St. 13th St. 13th St. Exit 114 I-65 North 12th St. Fall Creek Pkwy E Dr. Exit 113 Dr. MartinDr. Luther King, St. Jr. Indiana Ave. Exit 112A 11th St. Exit 113 tson Blvd. I-70 East ber Ro I-70 West 2 r 2 a c I-65 South s I-70 East NESCO O I-70 West I-65 North 10th St. 10th St. Neighborhoods I-65 South Upper Canal North Meridian St. Joseph St. Ransom Place 10th St. St. Joseph Fayette Street 9th St. Chatham Arch Indiana Ave. & Mass Ave Haughville Meridian St. WilsonSt. St. Clair St. Wishard Blvd. 3 Walnut St. 3 Walnut St. Exit 111 Indiana Avenue Fort Wayne Ave. & IUPUI Pennsylvania St. North St. North St. Riley Hospital Dr. Cottage Senate Ave. Barnhill Dr. Home Michigan St. Michigan St. ParkAve. Vermont St. Vermont St. California St. Beauty Ave. Vermont St. Massachusetts Ave. 4 4 Lockerbie St. Holy Illinois St. Blackford St. College Ave. Capitol Ave. University Blvd. Lockerbie Square Cross West St. New York St. New York St. Delaware St. Ohio St. I-70 East Alabama St. I-65 North New Jersey St. -

543 Indiana Ave Flyer.Ai

Museum INDIANA AVENUE WEST STREET MICHIGAN STREET SITE N For Sale or Lease BUILDING CAN BE DEMISED 543 Indiana Avenue, Indianapolis, IN 46202 GROUND FLOOR IDEAL FOR RESTAURANT: 3,722 S.F. 2ND AND 3RD FLOOR OFFERS GREAT VIEWS OF DOWNTOWN • First Floor can be Leased Apart from Full Building • 2nd Floor 3,420 S.F. / 3rd Floor 3,172 S.F. • Ideal for Delivery Service or Fast Casual Concepts • Full Balcaony on 2nd Floor with Stunning Views of Downtown and White River • Easy Access to IUPUI, Downtown & Hotels • Elevator Access - Can Lock Floors for Privacy • Full Kitchen & Upgraded Mechanicals • Ground Floor Rate NegoƟable • Fully Sprinkled Asking Price: $1,550,000 • Billboard Signage to Over 36,000 Vehicles Per Day • $18.00 S.F. Modified Gross • On Site Parking Meridian Eagle Broad 36 Creek Ripple Demographics: (1 & 3 mile radius / 2017 es mates) For addiƟonal informaƟon contact: 74 65 136 Indianapolis Popula on 15,090 Jacque Haynes, CCIM Clermont 70 Average HH Income $74,926 465 IMS jhaynes@midlandatlanƟc.us 70 Speedway Warren 465 Number of Businesses 4,945 Park Phone.317.580.9900 40 Number of Employees 134,504 36 74 65 70 52 40 Popula on 107,744 Mars Average HH Income $50,958 www.midlandatlanƟc.com Hill 74 Number of Businesses 8,821 Indianapolis Wanamaker @midlandatlanƟc International 465 Airport Number of Employees 203,392 70 Valley 67 Mills Southport 65 Indianapolis Office Camby 31 9000 Keystone Crossing, Suite 850, Indianapolis, IN 46240 MIDLAND ATLANTIC PROPERTIES • DEVELOPMENT • BROKERAGE • ACQUISITIONS • MANAGEMENT ed reliable but is not -

Downtown Livingtour 2014 6 Must-See Urban Properties

SPECIAL ADVERTISING SUPPLEMENT TO INDIANAPOLIS MONTHLY downtown livingtour 2014 6 must-see urban properties SEPtEMBEr 12&13 For details, see pages 4–5. ony valainis t event sponsors photo by by photo SPECIAL ADVERTISING SUPPLEMENT TO INDIANAPOLIS MONTHLY GREETINGS AND WELCOME TO DOWNTOWN! t’s an exciting time for downtown Indianapolis! Our dynamic city with its vibrant downtown offers plenty to experience, explore, and enjoy. From the 20,000 residents who call downtown home to the 22 million guests who visit every year, we thank you for your interest and welcome you. New residential options downtown, coupled with charm- ing historic neighborhoods with brand-new shopping and grocery options—and more on the way—show why the de- I mand for downtown living is at an all-time high. There’s a seem- ingly endless array of day and nighttime activities and entertainment from sporting events and concerts to live theater and cultural celebrations that enhance our quality of life. For example, we are so fortunate to have the Indianapolis Symphony Orchestra, Indiana Repertory Theatre, Madame Walker Theatre, and many other local theatres producing award-winning performances that allow us to enjoy world-class entertainment—usually within walking distance from each other. These venues share the spotlight with contemporary acts at the Farm Bureau Insurance Lawn at White River State Park, Bankers Life Fieldhouse, Old National Centre, Rathskeller, Cha- tham Tap, Slippery Noodle Inn, and other local hotspots. The Colts, Indians, Pacers, Fever, and our newest addition to the line-up of professional sports teams, pro soccer’s Indy Eleven, give us plenty of hometown teams for which to cheer. -

Pioneer Founders of Indiana 2014

The Society of Indiana Pioneers "To Honor the Memory and the Work of the Pioneers of Indiana" Pioneer Founders of Indiana 2014 The Society of Indiana Pioneers is seeking to identify Indiana Pioneers to recognize and honor their efforts in building early Indiana foundations. Each year, 15-20 counties are to be selected for honoring pioneers at each annual meeting. The task of covering all 92 counties will be completed by 2016, the year we celebrate the centennial of the founding of the Society of Indiana Pioneers. For 2014, the Indiana counties include the following: Adams, Decatur, Fountain, Grant, Jasper, Jay, Jennings, LaGrange, Marion Martin, Owen, Pulaski, Ripley, Spencer, Steuben, Vermillion, Wabash, Warrick Office: 140 North Senate Avenue, Indianapolis, Indiana 46204-2207 (317) 233-6588 www.indianapioneers.org [email protected] The Pioneer Founders of Indiana Program 2014 “To honor the memory and the work of the pioneers of Indiana” has been the purpose and motto of The Society of Indiana Pioneers from the very beginning. In fact, these words compose the second article of our Articles of Association. We carry out this mission of the Society in three distinct ways: 1.) we maintain a rich Pioneer Ancestor Database of proven ancestors of members across one hundred years; 2.) Spring and Fall Hoosier Heritage Pilgrimages to significant historic and cultural sites across Indiana; and 3.) educational initiatives, led by graduate fellowships in pioneer Indiana history at the master’s thesis and doctoral dissertation levels. To commemorate the Society’s centennial and the state’s bicentennial in 2016, the Society is doing something new and dipping its toes in the world of publishing.