Islands" of Memory As a Mechanism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Psychogenic and Organic Amnesia. a Multidimensional Assessment of Clinical, Neuroradiological, Neuropsychological and Psychopathological Features

Behavioural Neurology 18 (2007) 53–64 53 IOS Press Psychogenic and organic amnesia. A multidimensional assessment of clinical, neuroradiological, neuropsychological and psychopathological features Laura Serraa,∗, Lucia Faddaa,b, Ivana Buccionea, Carlo Caltagironea,b and Giovanni A. Carlesimoa,b aFondazione IRCCS Santa Lucia, Roma, Italy bClinica Neurologica, Universita` Tor Vergata, Roma, Italy Abstract. Psychogenic amnesia is a complex disorder characterised by a wide variety of symptoms. Consequently, in a number of cases it is difficult distinguish it from organic memory impairment. The present study reports a new case of global psychogenic amnesia compared with two patients with amnesia underlain by organic brain damage. Our aim was to identify features useful for distinguishing between psychogenic and organic forms of memory impairment. The findings show the usefulness of a multidimensional evaluation of clinical, neuroradiological, neuropsychological and psychopathological aspects, to provide convergent findings useful for differentiating the two forms of memory disorder. Keywords: Amnesia, psychogenic origin, organic origin 1. Introduction ness of the self – and a period of wandering. According to Kopelman [33], there are three main predisposing Psychogenic or dissociative amnesia (DSM-IV- factors for global psychogenic amnesia: i) a history of TR) [1] is a clinical syndrome characterised by a mem- transient, organic amnesia due to epilepsy [52], head ory disorder of nonorganic origin. Following Kopel- injury [4] or alcoholic blackouts [20]; ii) a history of man [31,33], psychogenic amnesia can either be sit- psychiatric disorders such as depressed mood, and iii) uation specific or global. Situation specific amnesia a severe precipitating stress, such as marital or emo- refers to memory loss for a particular incident or part tional discord [23], bereavement [49], financial prob- of an incident and can arise in a variety of circum- lems [23] or war [21,48]. -

Fullness, and Tinni- Tus

Neurology® Clinical Practice The evaluation of a patient with dizziness Kevin A. Kerber, MD Robert W. Baloh, MD Summary Dizziness is the quintessential symptom presenta- tion in all of clinical medicine. It can stem from a disturbance in nearly any system of the body. Pa- tient descriptions of the symptom are often vague and inconsistent, so careful probing is essential. The physical examination is performed by observ- ing the patient at rest and following simple move- ments or bedside tests. In general, no special tools are required. The causes of dizziness range from benign to life-threatening disorders, and features that distinguish among these may be subtle. When diagnostic testing is considered, parsimony should be the rule. Identifying common peripheral vestibu- lar disorders is a priority. Picking this “low hanging fruit” can be the key component to excluding more serious central causes of dizziness. eurologists play an important role in the evaluation and management of pa- tients with dizziness. The possibility of a serious neurologic disorder is un- Nnerving to front-line physicians who have ranked decision support for identifying central causes of vertigo as a top priority.1 Although dangerous cen- tral disorders do not commonly present as isolated dizziness, stroke and other neurologic disorders can occur in this manner. The history and physical examination are the critical elements in determining the management of these patients. In this article, we review the approach to the evaluation and management of patients with dizziness. History The first step in assessing a patient presenting with dizziness is to define the symptom (table 1). -

Vertebral Artery Dissection Presenting As Transient Global Amnesia: a Case Report and Review of Literature

Dementia and Neurocognitive Disorders 2014; 13: 46-49 CASE REPORT http://dx.doi.org/10.12779/dnd.2014.13.2.46 Vertebral Artery Dissection Presenting as Transient Global Amnesia: A Case Report and Review of Literature , Yeonsil Moon*, Seol-Heui Han* † Vertebral artery dissection is one of the most common causes of stroke in young adults. The course of the vertebral artery dissection is usually benign, and pure transient amnesia as an initial symptom has Department of Neurology*, Konkuk University Medical Center, Seoul; Center for Geriatric been rarely reported. We describe a patient with vertebral artery dissection who presented with acute Neuroscience Research, Institute of transient amnesia, and review the medical literatures about the pathophysiological mechanism of tran- Biomedical Science†, Konkuk University, sient global amenesia (TGA). This case could be a one of evidence which supports the cerebrovascular Seoul, Korea mechanism of TGA. Received: May 19, 2014 Revision received: June 26, 2014 Accepted: June 26, 2014 Address for correspondence Seol-Heui Han, M.D. Department of Neurology, Konkuk University School of Medicine, 120-1 Neungdong-ro, Gwangjin-gu, Seoul 143-729, Korea Tel: +82-2-2030-7561 Fax: +82-2-2030-7469 E-mail: [email protected] Key Words: Transient global amnesia, Vertebral artery dissection, Cerebrovascular Vertebral artery dissection is one of the most common longed cognitive decline and review the medical literatures causes of stroke in young adults [1]. The course of the verte- about the pathophysiological mechanism of transient global bral artery dissection is usually benign, but seldom reaches to amenesia (TGA). severe complication, such as brainstem infarction, subarach- noid hemorrhage (SAH) or death [2]. -

Second Edition

COVID-19 Evidence Update COVID-19 Update from SAHMRI, Health Translation SA and the Commission on Excellence and Innovation in Health Updated 4 May 2020 – 2nd Edition “What is the prevalence, positive predictive value, negative predictive value, sensitivity and specificity of anosmia in the diagnosis of COVID-19?” Executive Summary There is widespread reporting of a potential link between anosmia (loss of smell) and ageusia (loss of taste) and SARS-COV-2 infection, as an early sign and with sudden onset predominantly without nasal obstruction. There are calls for anosmia and ageusia to be recognised as symptoms for COVID-19. Since the 1st edition of this briefing (25 March 2020), there has been a significant expansion of literature on this topic, including 3 systematic reviews. Predictive value: The reported prevalence of anosmia/hyposmia and ageusia/hypogeusia in SARS-COV-2 positive patients are in the order of 36-68% and 33-71% respectively. There are reports of anosmia as the first symptom in some patients. Estimates from one study for hyposmia and hypogeusia: • Positive likelihood ratios: 4.5 and 5.8 • Sensitivity: 46% and 62% • Specificity: 90% and 89% The US Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has added new loss or taste or smell to its list of recognised symptoms for SARS-COV-2 infection. To date, the World Health Organization has not. Conclusion: There is sufficient evidence to warrant adding loss of taste and smell to the list of symptoms for COVID-19 and promoting this information to the public. Context • Early detection of COVID-19 is key to the ongoing management of the pandemic. -

COVID-19 Vaccines: Update on Allergic Reactions, Contraindications, and Precautions

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Center for Preparedness and Response COVID-19 Vaccines: Update on Allergic Reactions, Contraindications, and Precautions Clinician Outreach and Communication Activity (COCA) Webinar Wednesday, December 30, 2020 Continuing Education Continuing education will not be offered for this COCA Call. To Ask a Question ▪ All participants joining us today are in listen-only mode. ▪ Using the Webinar System – Click the “Q&A” button. – Type your question in the “Q&A” box. – Submit your question. ▪ The video recording of this COCA Call will be posted at https://emergency.cdc.gov/coca/calls/2020/callinfo_123020.asp and available to view on-demand a few hours after the call ends. ▪ If you are a patient, please refer your questions to your healthcare provider. ▪ For media questions, please contact CDC Media Relations at 404-639-3286, or send an email to [email protected]. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Center for Preparedness and Response Today’s First Presenter Tom Shimabukuro, MD, MPH, MBA CAPT, U.S. Public Health Service Vaccine Safety Team Lead COVID-19 Response Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Center for Preparedness and Response Today’s Second Presenter Sarah Mbaeyi, MD, MPH CDR, U.S. Public Health Service Clinical Guidelines Team COVID-19 Response Centers for Disease Control and Prevention National Center for Immunization & Respiratory Diseases Anaphylaxis following mRNA COVID-19 vaccination Tom Shimabukuro, MD, MPH, MBA CDC COVID-19 Vaccine -

Dizziness Related to Anxiety and Stress

Dizziness Related to Anxiety and Stress Author: Laura O. Morris, PT, NCS Fact Sheet Why does anxiety and stress cause me to be dizzy? Dizziness is a common symptom of anxiety stress and, and If one is experiencing anxiety, dizziness can result. On the other hand, dizziness can be anxiety producing. The vestibular system is responsible for sensing body position and movement in our surroundings. The vestibular system is made up of an inner ear on each side, specific areas of the brain, and the nerves that connect them. This system is responsible for the sense of dizziness when things go wrong. Scientists believe that the areas in the brain responsible for dizziness interact with the areas responsible for anxiety, and cause both symptoms. Produced by The dizziness that accompanies anxiety is often described as a sense of lightheadedness or wooziness. There may be a feeling of motion or spinning inside rather than in the environment. Sometimes there is a sense of swaying even though you are standing still. Environments like grocery stores, crowded malls or wide-open spaces may cause a sense of imbalance and disequilibrium. These symptoms are caused by legitimate physiologic changes within the brain. A Special Interest Group of If there is an abnormality in the vestibular system, the symptom of dizziness can be the result. If one already has a tendency toward anxiety, dizziness from the vestibular system and anxiety can interact, making symptoms worse. Often the anxiety and the dizziness must be treated together in order for improvement to be made. How does physical therapy help? Contact us: ANPT Scientists are starting to better understand how dizziness and 5841 Cedar Lake Rd S. -

PAVOL JOZEF ŠAFARIK UNIVERSITY in KOŠICE Dissociative Amnesia: a Clinical and Theoretical Reconsideration DEGREE THESIS

PAVOL JOZEF ŠAFARIK UNIVERSITY IN KOŠICE FACULTY OF MEDICINE Dissociative amnesia: a clinical and theoretical reconsideration Paulo Alexandre Rocha Simão DEGREE THESIS Košice 2017 PAVOL JOZEF ŠAFARIK UNIVERSITY IN KOŠICE FACULTY OF MEDICINE FIRST DEPARTMENT OF PSYCHIATRY Dissociative amnesia: a clinical and theoretical reconsideration Paulo Alexandre Rocha Simão DEGREE THESIS Thesis supervisor: Mgr. MUDr. Jozef Dragašek, PhD., MHA Košice 2017 Analytical sheet Author Paulo Alexandre Rocha Simão Thesis title Dissociative amnesia: a clinical and theoretical reconsideration Language of the thesis English Type of thesis Degree thesis Number of pages 89 Academic degree M.D. University Pavol Jozef Šafárik University in Košice Faculty Faculty of Medicine Department/Institute Department of Psychiatry Study branch General Medicine Study programme General Medicine City Košice Thesis supervisor Mgr. MUDr. Jozef Dragašek, PhD., MHA Date of submission 06/2017 Date of defence 09/2017 Key words Dissociative amnesia, dissociative fugue, dissociative identity disorder Thesis title in the Disociatívna amnézia: klinické a teoretické prehodnotenie Slovak language Key words in the Disociatívna amnézia, disociatívna fuga, disociatívna porucha identity Slovak language Abstract in the English language Dissociative amnesia is a one of the most intriguing, misdiagnosed conditions in the psychiatric world. Dissociative amnesia is related to other dissociative disorders, such as dissociative identity disorder and dissociative fugue. Its clinical features are known -

Paranoid Or Bizarre Delusions, Or Disorganized Speech and Thinking, and It Is Accompanied by Significant Social Or Occupational Dysfunction

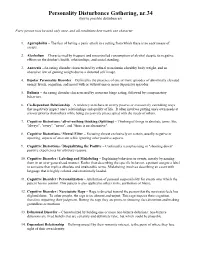

Personality Disturbance Gathering, nr.34 (key to possible disturbances) Every person may be used only once, and all conditions best match one character. 1. Agoraphobia – The fear of having a panic attack in a setting from which there is no easy means of escape. 2. Alcoholism – Characterized by frequent and uncontrolled consumption of alcohol despite its negative effects on the drinker's health, relationships, and social standing. 3. Anorexia –An eating disorder characterized by refusal to maintain a healthy body weight, and an obsessive fear of gaining weight due to a distorted self image. 4. Bipolar Personality Disorder – Defined by the presence of one or more episodes of abnormally elevated energy levels, cognition, and mood with or without one or more depressive episodes. 5. Bulimia – An eating disorder characterized by recurrent binge eating, followed by compensatory behaviors. 6. Co-Dependant Relationship – A tendency to behave in overly passive or excessively caretaking ways that negatively impact one's relationships and quality of life. It often involves putting one's own needs at a lower priority than others while being excessively preoccupied with the needs of others. 7. Cognitive Distortions / all-of-nothing thinking (Splitting) – Thinking of things in absolute terms, like "always", "every", "never", and "there is no alternative". 8. Cognitive Distortions / Mental Filter – Focusing almost exclusively on certain, usually negative or upsetting, aspects of an event while ignoring other positive aspects. 9. Cognitive Distortions / Disqualifying the Positive – Continually reemphasizing or "shooting down" positive experiences for arbitrary reasons. 10. Cognitive Disorder / Labeling and Mislabeling – Explaining behaviors or events, merely by naming them in an over-generalized manner. -

Practitioner's Guide to the Dizzy Patient

PRACTITIONER’S GUIDE TO THE DIZZY PATIENT Alan L. Desmond, AuD Wake Forest Baptist Health Otolaryngology ABOUT THE PRACTITIONER’S GUIDE TO THE DIZZY PATIENT The information in this guide has been reviewed for accuracy by specialists in Audiology, Otolaryngology, Neurology, Physical Therapy and Emergency Medicine ABOUT THE AUTHOR Alan L. Desmond, AuD, is the director of the Balance Disorders Program at Wake Forest Baptist Medical Center and a faculty member of Wake Forest School of Medicine. He is the author of Vestibular Function: Evaluation and Treatment (Thieme, 2004), and Vestibular Function: Clinical and Practice Management (Thieme, 2011). He is a co-author of Clinical Practice Guideline: Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo. He serves as a representative of the American Academy of Audiology at the American Medical Association and received the Academy Presidents Award in 2015 for contributions to the profession. He also serves on several advisory boards and has presented numerous articles and lectures related to vestibular disorders. HOW TO MAKE AN APPOINTMENT WITH THE WAKE FOREST BAPTIST HEALTH BALANCE DISORDERS TEAM Physician referrals can be made through the STAR line at 336-713-STAR (7827). PRACTITIONER’S GUIDE TO THE DIZZY PATIENT TABLE OF CONTENTS How to Use the Practitioner’s Guide to the Dizzy Patient . 2 Typical Complaints of Various Vestibular and non-Vestibular Disorders . 3 Structure and Function of the Vestibular System . 4 Categorizing the Dizzy Patient . 5 Timing and Triggers of Common Disorders . 6 Initial Examination Checklist for Acute Vertigo: Peripheral versus Central . 7 Diagnosing Acute Vertigo . 8 Fall Risk Questionnaire . 10 Physician’s Guide to Fall Risk Questionnaire . -

Neuropsychiatric Manifestations of COVID-19 Can Be Clustered in Three

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Neuropsychiatric manifestations of COVID‑19 can be clustered in three distinct symptom categories Fatemeh Sadat Mirfazeli1,8, Atiye Sarabi‑Jamab2,8, Amin Jahanbakhshi3, Alireza Kordi4, Parisa Javadnia4, Seyed Vahid Shariat1, Oldooz Aloosh5, Mostafa Almasi‑Dooghaee6 & Seyed Hamid Reza Faiz7* Several studies have reported clinical manifestations of the new coronavirus disease. However, few studies have systematically evaluated the neuropsychiatric complications of COVID‑19. We reviewed the medical records of 201 patients with confrmed COVID‑19 (52 outpatients and 149 inpatients) that were treated in a large referral center in Tehran, Iran from March 2019 to May 2020. We used clustering approach to categorize clinical symptoms. One hundred and ffty‑one patients showed at least one neuropsychiatric symptom. Limb force reductions, headache followed by anosmia, hypogeusia were among the most common neuropsychiatric symptoms in COVID‑19 patients. Hierarchical clustering analysis showed that neuropsychiatric symptoms group together in three distinct groups: anosmia and hypogeusia; dizziness, headache, and limb force reduction; photophobia, mental state change, hallucination, vision and speech problem, seizure, stroke, and balance disturbance. Three non‑ neuropsychiatric cluster of symptoms included diarrhea and nausea; cough and dyspnea; and fever and weakness. Neuropsychiatric presentations are very prevalent and heterogeneous in patients with coronavirus 2 infection and these heterogeneous presentations may be originating from diferent underlying mechanisms. Anosmia and hypogeusia seem to be distinct from more general constitutional‑like and more specifc neuropsychiatric symptoms. Skeletal muscular manifestations might be a constitutional or a neuropsychiatric symptom. In December 2019 a number of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) were reported in Wuhan, China that became eventually a pandemic infection with over 8 million reported cases until June 2020 1. -

Cognitive Disorders: a Perspective from the Neurology Clinic

This is a repository copy of Functional (Psychogenic) Cognitive Disorders: A Perspective from the Neurology Clinic. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/93827/ Version: Accepted Version Article: Stone, J., Pal, S., Blackburn, D. et al. (3 more authors) (2015) Functional (Psychogenic) Cognitive Disorders: A Perspective from the Neurology Clinic. Journal of Alzheimer's Disease, 49 (s1). S5-S17. ISSN 1387-2877 https://doi.org/10.3233/JAD-150430 Reuse Unless indicated otherwise, fulltext items are protected by copyright with all rights reserved. The copyright exception in section 29 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 allows the making of a single copy solely for the purpose of non-commercial research or private study within the limits of fair dealing. The publisher or other rights-holder may allow further reproduction and re-use of this version - refer to the White Rose Research Online record for this item. Where records identify the publisher as the copyright holder, users can verify any specific terms of use on the publisher’s website. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ Functional (psychogenic) memory disorders - a perspective from the neurology clinic Jon Stone1 , Suvankar Pal1,2, Daniel Blackburn2, Markus Reuber2, Parvez Thekkumpurath1, Alan Carson1,3 1Centre for Clinical Brain Sciences, University of Edinburgh, Western General Hospital, Crewe Rd, Edinburgh EH4 2XU, UK. -

Dizziness: Approach to Evaluation and Management HERBERT L

Dizziness: Approach to Evaluation and Management HERBERT L. MUNCIE, MD, Louisiana State University School of Medicine, New Orleans, Louisiana SUSAN M. SIRMANS, PharmD, University of Louisiana at Monroe School of Pharmacy, Monroe, Louisiana ERNEST JAMES, MD, Louisiana State University School of Medicine, New Orleans, Louisiana Dizziness is a common yet imprecise symptom. It was traditionally divided into four categories based on the patient’s history: vertigo, presyncope, disequilibrium, and light-headedness. However, the distinction between these symp- toms is of limited clinical usefulness. Patients have difficulty describing the quality of their symptoms but can more consistently identify the timing and triggers. Episodic vertigo triggered by head motion may be due to benign parox- ysmal positional vertigo. Vertigo with unilateral hearing loss suggests Meniere disease. Episodic vertigo not associated with any trigger may be a symptom of vestibular neuritis. Evaluation focuses on determining whether the etiology is peripheral or central. Peripheral etiologies are usually benign. Central etiologies often require urgent treatment. The HINTS (head-impulse, nystagmus, test of skew) examination can help distinguish peripheral from central etiologies. The physical examination includes orthostatic blood pressure measurement, a full cardiac and neurologic examina- tion, assessment for nystagmus, and the Dix-Hallpike maneuver. Laboratory testing and imaging are not required and are usually not helpful. Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo can