Chek Jawa, Pulau Ubin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Singapore | October 17-19, 2019

BIOPHILIC CITIES SUMMIT Singapore | October 17-19, 2019 Page 3 | Agenda Page 5 | Site Visits Page 7 | Speakers Meet the hosts Biophilic Cities partners with cities, scholars and advocates from across the globe to build an understanding of the importance of daily contact with nature as an element of a meaningful urban life, as well as the ethical responsibility that cities have to conserve global nature as shared habitat for non- human life and people. Dr. Tim Beatley is the Founder and Executive Director of Biophilic Cities and the Teresa Heinz Professor of Sustainable Communities, in the Department of Urban and Environmental Planning, School of Architecture at the University of Virginia. His work focuses on the creative strategies by which cities and towns can bring nature into the daily lives of thier residents, while at the same time fundamentally reduce their ecological footprints and becoming more livable and equitable places. Among the more than variety of books on these subjects, Tim is the author of Biophilic Cities and the Handbook of Bophilic City Planning & Design. The National Parks Board (NParks) of Singapore is committed to enhancing and managing the urban ecosystems of Singapore’s biophilic City in a Garden. NParks is the lead agency for greenery, biodiversity conservation, and wildlife and animal health, welfare and management. The board also actively engages the community to enhance the quality of Singapore’s living environment. Lena Chan is the Director of the National Biodiversity Centre (NBC), NParks, where she leads a team of 30 officers who are responsible for a diverse range of expertise relevant to biodiversity conservation. -

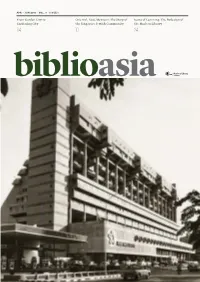

Apr–Jun 2013

VOL. 9 iSSUe 1 FEATURE APr – jUn 2013 · vOL. 9 · iSSUe 1 From Garden City to Oriental, Utai, Mexican: The Story of Icons of Learning: The Redesign of Gardening City the Singapore Jewish Community the Modern Library 04 10 24 01 BIBLIOASIA APR –JUN 2013 Director’s Column Editorial & Production “A Room of One’s Own”, Virginia Woolf’s 1929 essay, argues for the place of women in Managing Editor: Stephanie Pee Editorial Support: Sharon Koh, the literary tradition. The title also makes for an apt underlying theme of this issue Masamah Ahmad, Francis Dorai of BiblioAsia, which explores finding one’s place and space in Singapore. Contributors: Benjamin Towell, With 5.3 million people living in an area of 710 square kilometres, intriguing Bernice Ang, Dan Koh, Joanna Tan, solutions in response to finding space can emerge from sheer necessity. This Juffri Supa’at, Justin Zhuang, Liyana Taha, issue, we celebrate the built environment: the skyscrapers, mosques, synagogues, Noorashikin binte Zulkifli, and of course, libraries, from which stories of dialogue, strife, ambition and Siti Hazariah Abu Bakar, Ten Leu-Jiun Design & Print: Relay Room, Times Printers tradition come through even as each community attempts to find a space of its own and leave a distinct mark on where it has been and hopes to thrive. Please direct all correspondence to: A sense of sanctuary comes to mind in the hubbub of an increasingly densely National Library Board populated city. In Justin Zhuang’s article, “From Garden City to Gardening City”, he 100 Victoria Street #14-01 explores the preservation and the development of the green lungs of Sungei Buloh, National Library Building Singapore 188064 Chek Jawa and, recently, the Rail Corridor, as breathing spaces of the city. -

How to Prepare the Final Version of Your Manuscript for the Proceedings of the 11Th ICRS, July 2007, Ft

Proceedings of the 12th International Coral Reef Symposium, Cairns, Australia, 9-13 July 2012 22A Social, economic and cultural perspectives Conservation of our natural heritage: The Singapore experience Jeffrey Low, Liang Jim Lim National Biodiversity Centre, National Parks Board, 1 Cluny Road, Singapore 259569 Corresponding author: [email protected] Abstract. Singapore is a highly urbanised city-state of approximately 710 km2 with a population of almost 5 million. While large, contiguous natural habitats are uncommon in Singapore, there remains a large pool of biodiversity to be found in its four Nature Reserves, 20 Nature Areas, its numerous parks, and other pockets of naturally vegetated areas. Traditionally, conservation in Singapore focused on terrestrial flora and fauna; recent emphasis has shifted to marine environments, showcased by the reversal of development works on a unique intertidal shore called Chek Jawa (Dec 2001), the legal protection of Sungei Buloh Wetland Reserve (mangrove and mudflat habitats) and Labrador Nature Reserve (coastal habitat) in 2002, the adoption of a national biodiversity strategy (September 2009) and an integrated coastal management framework (November 2009). Singapore has also adopted the “City in a Garden” concept, a 10-year plan that aims to not only heighten the natural infrastructure of the city, but also to further engage and involve members of the public. The increasing trend of volunteerism, from various sectors of society, has made “citizen-science” an important component in many biodiversity conservation projects, particularly in the marine biodiversity-rich areas. Some of the key outputs from these so-called “3P” (people, public and private) initiatives include confirmation of 12 species of seagrasses in Singapore (out of the Indo-Pacific total of 23), observations of new records of coral reef fish species, long term trends on the state of coral reefs in one of the world's busiest ports, and the initiation of a Comprehensive Marine Biodiversity Survey project. -

ST/LIFE/PAGE<LIF-008>

C8 life happenings | THE STRAITS TIMES | FRIDAY, MARCH 13, 2020 | FILMS John Lui Film Correspondent recommends Roll With The Trolls Movie Event Trolls World Tour (2020, PG) is the sequel to the 2016 animated film Picks Trolls. It tells the story of Poppy and Branch, who discover they are from one of six Troll tribes, each dedicated Film to a different genre of music. They set out to unite the tribes as Queen Barb, a member of hard-rock royalty, plans to destroy all other kinds of music. The ticket price includes an activity pack, sand-art activity and chocolate popcorn with marshmallow. WHERE: Cathay Cineplex Parkway Parade, Level 7 Parkway Parade, 80 Marine Parade Road MRT: Eunos WHEN: Tomorrow, 10.30am - 3pm ADMISSION: $15 (single ticket), $58 (family bundle of four tickets) INFO: www.cathaycineplexes.com.sg In The Name Of The Land (PG13) Pierre is 25 when he returns from Wyoming to find Claire, his fiancee, has taken over the family farm. Two decades later, despite the expansion of his farm and family, the accumulated debts and work take a toll on Pierre. The screening will be followed by a live Skype question- and-answer session with French director Edouard Bergeon (nominated for Cesar Awards: Best First Feature Film and Audience Award) and writer Emmanuel Courcol (Ceasefire, 2016; Face Down, 2015). Part of the Francophonie Festival. WHERE: Alliance Francaise, 1 Sarkies Road MRT: Newton WHEN: Wed, 8pm ADMISSION: $15 INFO: alliancefrancaise.org.sg The Lighthouse (M18) From Robert Eggers, the film-maker behind modern horror masterpiece PRINCESS MONONOKE (PG) work, Spirited Away (2001). -

The Singapore Urban Systems Studies Booklet Seriesdraws On

Biodiversity: Nature Conservation in the Greening of Singapore - In a small city-state where land is considered a scarce resource, the tension between urban development and biodiversity conservation, which often involves protecting areas of forest from being cleared for development, has always been present. In the years immediately after independence, the Singapore government was more focused on bread-and-butter issues. Biodiversity conservation was generally not high on its list of priorities. More recently, however, the issue of biodiversity conservation has become more prominent in Singapore, both for the government and its citizens. This has predominantly been influenced by regional and international events and trends which have increasingly emphasised the need for countries to show that they are being responsible global citizens in the area of environmental protection. This study documents the evolution of Singapore’s biodiversity conservation efforts and the on-going paradigm shifts in biodiversity conservation as Singapore moves from a Garden City to a City in a Garden. The Singapore Urban Systems Studies Booklet Series draws on original Urban Systems Studies research by the Centre for Liveable Cities, Singapore (CLC) into Singapore’s development over the last half-century. The series is organised around domains such as water, transport, housing, planning, industry and the environment. Developed in close collaboration with relevant government agencies and drawing on exclusive interviews with pioneer leaders, these practitioner-centric booklets present a succinct overview and key principles of Singapore’s development model. Important events, policies, institutions, and laws are also summarised in concise annexes. The booklets are used as course material in CLC’s Leaders in Urban Governance Programme. -

Nparks Biodiversity Week (For Community) in Conjunction with the International Day for Biological Diversity, Members of the Publ

ANNEX NParks Biodiversity Week (for Community) In conjunction with the International Day for Biological Diversity, members of the public can participate in a series of Community in Nature (CIN) activities from 16 to 22 May 2016. Interested participants are welcome to register with NParks at http://www.nparks.gov.sg/biodiversityweek to participate in the activities. Activity Details Sungei Buloh Wetland Reserve Members of the public are invited to share Photo Exhibition (New) photos of their experiences at Sungei Buloh Wetland Reserve. Interested participants can email their photos and accompanying captions about their experience at Sungei Buloh Wetland Reserve, as well as their name, contact number and email address with the subject “SBWR Moments” to [email protected] by 19 May 2016. Selected photos will be exhibited at the Sungei Buloh Wetland Reserve Visitor Centre from 22 May to 30 June 2016. For more information, visit https://www.nparks.gov.sg/gardens-parks- and-nature/parks-and-nature- reserves/sungei-buloh-wetland-reserve. Firefly Survey @ Pasir Ris Park (New) Volunteers can survey the population of fireflies and firefly larvae at Pasir Ris Park Mangrove as part of the NParks CIN Biodiversity Watch. Date: 20 and 21 May 2016 Time: 7.30pm to 10.00pm Meeting Point: Carpark C of Pasir Ris Park Fees: Free Interested participants can email their name, contact number, email address and preferred date to [email protected] and [email protected]. Registration is on a first-come, first-served basis, and will close when all available slots are taken up, or on 9 May 2016, whichever comes first. -

Volunteer-Opportunities.Pdf

Choose from a wide range of volunteer opportunities and find an area that suits your interests and skillset: Outreach & Events Be involved in preparing for and running exciting events for the School & Corporate Programme community. Nature Education Looking for platforms to involve your company or school in conservation, Be a guide in our parks and gardens, and share your knowledge Biodiversity Volunteering at Bike Clinics research, outreach or education initiatives? These group volunteering Roadshows Park Events Park Connector on history, heritage, as well as flora and fauna with visitors. Central Nature Fort Canning Park Network activities will cultivate a love for the environment and promote a sense of ownership of our natural heritage: Reserve HortPark Community Nature Appreciation Mangrove Guided Walk Sungei Buloh Community in Plant-a-Tree Junior Guide Wetland Reserve Networking Garden Festival Walks Pasir Ris Park Nature Programe Programme Programme Central Nature Reserve Pulau Ubin Rides Park Connector Singapore Sungei Buloh Wetland Reserve Nature & Heritage Walk Network Garden Festival Fort Canning Park Gardeners’ Coney Island The Southern Ridges Day Out Bishan-Ang Mo Kio Park HortPark PCN Telok Ayer Park Appreciation Days Children’s Programmes Empress Place & Jezebel Artists Park Connector Esplanade Park Painting Central Nature Reserve HortPark Network Operation No Release Other Guide Opportunities Art in Nature Habitat Car Free Central Nature Reserve Sisters’ Island Marine Park Central Nature Enhancement Horticulture Guided Walk Sundays SG Reserve Civic District Operation Deadline Istana Open House Nature Play an active role in supporting Work closely with our horticulturists Pulau Ubin and promoting Singapore’s and support them in managing the Guided Walk natural heritage by maintaining landscapes in parks and gardens. -

Issue 58 Apr – Jun 2016

ISSUE 58 APR – JUN 2016 Guarding Our Sustaining A Living In Greenery Green City Nature THE PRESERVATION RESOURCE CONSTRAINTS OF OTTERS, PENGUINS OF SINGAPORE’S COMPEL SMARTER AND ROBOTIC TREES GREEN SPACES PLANNING AND SOLUTIONS EXPERIENCE SINGAPORE NATURE, new and old The signifi cant role of fl ora and fauna in Singapore life A NEWSLETTER OF THE SINGAPORE COOPERATION PROGRAMME ExpSG Cover V2.indd 2 14/6/16 10:37 AM Ed’s Note CONTENTS 3 FOCUS Guarding our greenery Dear readers, As its ultra-urban environment continues to grow, protecting and reen is the theme for this issue of Experience Singapore. preserving Singapore’s green spaces The ‘green spaces’ that make Singapore a ‘City in a becomes an increasingly important aim. G Garden’, that is. Nature reserves in land-scarce Singapore account for 3,300 hectares of our land mass. Close to a tenth REFLECTIONS of the island state is devoted to green spaces. Guarding our 6 greenery reveals why protecting and preserving these spaces Sustaining a green city is an important aim. Singapore’s whole-of-government approach Living in nature gives an idea of the fl ora and fauna that towards sustainable development in the abound in Singapore (who would have associated penguins and face of resource constraints otters with this urbanised city-state?) as well as how policies and schemes enable this biodiversity to fl ourish. 8 IN SINGAPORE The helping hands of many passionate players behind- Living in nature the-scenes play a huge part too. Nurturing nature puts the Though wired-up, Singapore’s fl ora spotlight on four such individuals, including a marine scientist and fauna abound in biodiversity and an arborist, who ensure that Singapore’s green spaces get — both indigenous and imported. -

Singapore Bucket List Here Are 30 Activities for Your Singapore Bucket List If You Are Visiting Singapore with Kids

Singapore Bucket List Here are 30 activities for your Singapore Bucket List if you are visiting Singapore with kids. Singapore is an expensive city to visit, so where possible we have included links to discounted tickets, and highlighted which activities are FREE! Scroll down for a checklist so you can tick off the attractions and activities as you go. Have fun! 1. Singapore Zoo A visit to Singapore with kids wouldn’t be complete without a trip to the Singapore Zoo. Often regarded as one of the best zoos in the world, the Singapore Zoo is set in a natural rainforest setting with spacious landscaped enclosures. Don’t miss Breakfast with the Orang Utans! Read all our Tips for Visiting Singapore Zoo here. Click here to buy discounted tickets. 2. Jurong Bird Park The Jurong Bird Park houses over 8,000 birds from over 600 species and is set in a beautifully landscaped park. Visit the world’s largest walk-in aviary, feed the Loris, Ostriches and Pelicans and watch the fun shows, including Birds n Buddies Show and the Thunderstorm Experience. Click here to buy discounted tickets. 3. SEA Aquarium There is an amazing variety of sea creatures to see at the SEA Aquarium in Resorts World Sentosa – over 800 species are represented across the 49 different habitats. With over 100,000 marine creatures in all, it is hard not to be impressed – especially when you reach the grand finale: the Open Ocean – a panoramic marine vista complete with manta rays, sharks, and goliath grouper. Click here to buy discounted tickets. -

Conserving Our Biodiversity Singapore’S National Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan

Conserving Our Biodiversity Singapore’s National Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan National Parks Board 2009 Conserving Our Biodiversity 2009 Contents 3 Introduction 5 Principles & Goals Strategies and Actions 6 Strategy 1 Safeguard Our Biodiversity 9 Strategy 2 Consider Biodiversity Issues in Policy and Decision-making 11 Strategy 3 Improve Knowledge of Our Biodiversity and the Natural Environment 14 Strategy 4 Enhance Education and Public Awareness 17 Strategy 5 Strengthen Partnerships with All Stakeholders and Promote International Collaboration 20 Monitoring and Evaluation 2 Conserving Our Biodiversity 2009 Introduction “Conserving Our Biodiversity” maps out Singapore’s master plan for Singapore Today — A Garden City, A Haven biodiversity. It aims to promote biodiversity conservation, keeping for Biodiversity in mind that as a densely populated country with no hinterland, we would have to adopt a pragmatic approach to conservation and Singapore’s green policies, beginning with the “Garden City” plan develop unique solutions to our challenges. It intends to establish in the 1960s, and continuing into the next century as a “City in a both policy frameworks and specific measures to ensure better Garden” vision, have transformed the city-state into a distinctive and planning and co-ordination in the sustainable use, management and vibrant global city. The clean and green environment mitigates the conservation of our biodiversity. harsh concrete urban environment and improves our quality of life. This has allowed Singapore to meet the lifestyle and recreational Biodiversity conservation cannot be achieved with only efforts from needs of an increasingly sophisticated population, and enhanced one agency. A holistic approach must be adopted and the inputs Singapore’s attractiveness as a destination for foreign businesses of various public sector agencies and nature groups have been and talents. -

ST/LIFE/PAGE<LIF-007>

| FRIDAY, JULY 13, 2018 | THE STRAITS TIMES | happenings life D7 John Lui Film Correspondent and Yip Wai Yee Entertainment Correspondent Picks recommend Film SHOPLIFTERS (M18) 121 minutes/ Ideas explored in this winner of the Cannes Film Festival’s highest prize, the Palme d’Or, include the meaning of family and how society’s definition of family often runs counter to how people actually behave. These are familiar themes for fans of Japanese director Hirokazu Kore-eda’s work, but here, they are packaged in a story that might be his strongest and most accessible yet. A crew of petty thieves and day labourers find a pre-schooler who appears to be abused. The older man, Osamu (Lily Franky, right), wants to give shelter to the girl, but the others in the group say she should be returned to her family. The film also stars Kirin Kiki (far right). John Lui JJANG WEDNESDAY PHOTOS: GOLDEN Fans of South Korean films should VILLAGE keep their Wednesdays free because one new Korean movie will be screened every hump day for six consecutive weeks, from now until the middle of next month. One of the films is crime thriller The Vanished (2018), about the mysterious disappearance of a powerful woman’s corpse from the morgue. Another is romantic comedy What A Man Wants (2018, right, with Lee El and Shin Ha-kyun), about how a married taxi driver’s cheating ways start to rub off on his brother-in-law. HONG KONG FILM FESTIVAL Better yet, all of them will be Sounds like a “jjang” (Korean slang In Hong Kong director Peter Chan’s showing in their original Cantonese for awesome) line-up. -

Pocket Singapore (Lonely Planet Pocket Guide)

Contents QuickStart Guide Welcome to Singapore Singapore Top Sights Singapore Local Life Singapore Day Planner Need to Know Explore Singapore Colonial District, the Quays & Marina Bay Orchard Road Chinatown, CBD & Tanjong Pagar Little India & Kampong Glam Sentosa Holland Village & Tanglin Village Southwest Singapore The Best of Singapore Singapore's Best Walks Colonial Singapore New-Millennium Singapore Singapore's B est... Tours Festivals Shopping Street Food Dining for Kids Drinking Entertainment Views & Vistas For Free Museums Escapes Survival Guide Before You Go Arriving in Singapore Getting Around Essential Information Language Behind the Scenes Our Writer Singapor e Neighbourhoods Colonial District, the Quays & Marina Bay Orchard Road Chinatown, CBD & Tanjong Pagar Little India & Kampong Glam Sentosa Holland Village & Tanglin Village Southwest Singapore Welcome to Singapore Merlion, designed by Fraser Brunner, Merlion Park, Marina Bay (Map Click here) RICHARD L’ANSON/LONELY PLANET IMAGES © Smart, sharp and just a little sexy, Singapore is Southeast Asia’s new ‘It kid’, subverting staid old stereotypes with ambitious architecture, dynamic museums, celebrity chefs and hip boutiques. Spike it all with smoky temples, gut-rumble- inducing food markets and pockets of steamy jungle, and you too might find that Asia’s ‘wallflower’ is a much more intriguing bloom than you ever gave it credit for. Sing apore Top Sights Singapore Zoo (Click here) Singapore Zoo is one of the world’s most inviting, enlightened animal sanctuaries, and a family- friendly must. Breakfast with orang-utans, sail on a jungle-fringed reservoir and purr over rare white tigers. FELIX HUG/LONELY PLANET IMAGES © Singapore T op Sights Singapore Botanic Gardens (Click here) Singapore’s Garden of Eden is the perfect antidote to the city’s rat-race tendencies.