A Public Health Approach to Community Violence

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The TTC Belongs to Toronto

TAKE ACTION! The TTC belongs to Call Premier Ford and the Minister of Transportation and tell them that the TTC belongs to Toronto! Urge them to oppose the plan to upload the TTC subway. It only Toronto. takes a few minutes and it makes a huge difference. We pay for it at the fare box and through our Hello, my name is ____ and my postal code is property taxes. But Premier Doug Ford wants ____. I strongly oppose your plan to upload the TTC because it will mean higher fares, break apart the TTC to break apart the TTC and take over the reduced service, and less say for riders. The subway. Transit riders will pay the price with TTC belongs to Toronto. We pay for it through higher fares, less say, and reduced service. our property taxes and our TTC fares. Consituency MPP Phone Etobicoke North Hon. Doug Ford 416-325-1941 higher fares Say no to higher fares Renfrew-Nipissing-Pembroke Hon. John Yakabuski 416-327-9200 Minister of Transportation A single TTC fare lets us transfer between bus, subway, and Etobicoke Centre Kinga Surma 416-325-1823 Parliamentary Assistant to Minister of Transportation streetcar. But the provincial transit agency Metrolinx is considering Beaches East York Rima Berns-McGown 416-325-2881 raising fares on the subway, charging more to ride longer Davenport Marit Stiles 416-535-3158 distances, and charging separate fares for the subways and buses. Don Valley East Michael Coteau 416-325-4544 If the province takes over the TTC subways, Metrolinx can carry Don Valley North Vincent Ke 416-325-3715 out its plan to charge us more. -

Turtle Island Reads

TABLE OF CONTENTS Video Summary & Related Content 3 Video Review 4 Before Viewing 5 While Viewing 6 Talk Prompts 9 After Viewing 12 The Story 15 Activity #1: “The Year of the Gun” Photo Essay 23 Activity #2: Take Action to Prevent Gun Violence 25 Sources 27 CREDITS News in Review is produced by Visit www.curio.ca/newsinreview for an archive of all CBC NEWS and curio.ca previous News In Review seasons. As a companion resource, go to www.cbc.ca/news for additional GUIDE articles. Writer: Chris Coates Editor: Sean Dolan CBC authorizes reproduction of material contained VIDEO in this guide for educational purposes. Please Host: Michael Serapio identify source. Senior Producer: Jordanna Lake News In Review is distributed by: Packaging Producer: Marie-Hélène Savard curio.ca | CBC Media Solutions Associate Producer: Francine Laprotte Supervising Manager: Laraine Bone © 2018 Canadian Broadcasting Corporation UNDER THE GUN: Toronto's War Against Firearm Violence Video duration – 14:25 In 2018 Canada’s largest city, Toronto, saw a massive increase in gun violence on its streets. Shootings were frequent and often flagrant, taking place in broad daylight and near children’s playgrounds. The numbers were so high it had people worried that gun deaths in 2018 would surpass that of the so-called “Summer of the Gun” back in 2005. Police, politicians, social advocates and residents all made suggestions on what was needed to decrease the gun violence. But the solutions remain as contentious as the problem. RELATED CONTENT • News in Review, January 2006 – Guns and Gangs: Toronto Fights Back • News in Review, February 2006 – Gang Wars: Bloodbath in Vancouver • News in Review, November 2008 – A Community Fights Gangs and Guns • News in Review, April 2013 – U.S. -

Doug Ford's Coming Tuition Announcement Is

Queen’s Park Today – Daily Report January 17, 2019 Quotation of the day “Doug Ford’s coming tuition announcement is going to turn out to be a smoke and mirrors exercise.” NDP MPP Chris Glover joined the chorus of post-secondary advocates concerned about today’s expected announcement about tuition fee cuts and OSAP changes. Today at Queen’s Park On the schedule The House is recessed until February 19. Government sources have told Queen’s Park Today, and reportedly the CBC, that cabinet will convene today. Sources say caucus meets as well. The premier’s office remains on lock. Premier watch A “Game Changer of the Year” award was bestowed upon Premier Doug Ford Tuesday night at a gala put on by the Coalition of Concerned Manufacturers and Businesses of Canada, a group that bills itself as a “growing and powerful voice” for manufacturing firms. The guest list for the Scarborough event included the finance and environment ministers, treasury board president and a few Tory MPPs. The premier wrapped up a two-day stint at the Detroit auto show earlier that day after meetings with executives from Toyota Canada and General Motors as well as Michigan Governor Gretchen Whitmer. In the park The Legislature’s public galleries are getting a fresh look. NDP ask why deputy minister didn’t recuse himself in Taverner hiring Let’s get ethical. That’s the message from NDP community safety critic Kevin Yarde, who wrote to soon-to-be-retired Cabinet Secretary Steve Orsini Wednesday asking why Deputy Community Safety Minister Mario Di Tommaso didn’t recuse himself from the hiring committee that picked Ron Taverner for OPP commissioner, given the pair’s history. -

Student Alliance

ONTARIO UNDERGRADUATE STUDENT ALLIANCE ADVOCACY CONFERENCE 2020 November 16-19th ABOUT OUSA The Ontario Undergraduate Student Alliance (OUSA) represents the interests of approximately 150,000 professional and undergraduate, full-time and part-time university students at eight student associations across Ontario. Our vision is for an accessible, affordable, accountable and high quality post-secondary education in Ontario. OUSA’s approach to advocacy is based on creating substantive, student driven, and evidence-based policy recommendations. INTRODUCTION Student leaders representing over 150,000 undergraduate students from across Ontario attended OUSA’s annual Student Advocacy Conference from November 16th to the 19th. Delegates met with over 50 MPPs from four political parties and sector stakeholders to discuss the future of post-secondary education in Ontario and advance OUSA’s advocacy priorities. Over five days, the student leaders discussed student financial aid, quality of education, racial equity, and student mental health. As we navigate the global pandemic, OUSA recommends improvements to the Ontario Student Assistance Program (OSAP), guidance and support for quality online learning, training and research to support racial equity, and funding for student mental health services. Overall, OUSA received a tremendous amount of support from members and stakeholders. ATTENDEES Julia Periera (WLUSU) Eric Chappell (SGA-AGÉ) Devyn Kelly (WLUSU) Nathan Barnett (TDSA) Mackenzy Metcalfe (USC) Rayna Porter (TDSA) Matt Reesor (USC) Ryan Tse (MSU) Megan Town (WUSA) Giancarlo Da-Ré (MSU) Abbie Simpson (WUSA) Tim Gulliver (UOSU-SÉUO) Hope Tuff-Berg (BUSU) Chris Yendt (BUSU) Matthew Mellon (AMS) Alexia Henriques (AMS) Malek Abou-Rabia (SGA-AGÉ) OUSA MET WITH A VARIETY OF STAKEHOLDERS MPPS CABINET MINISTERS Minister Michael Tibollo MPP Stephen Blais Office of Minister Monte McNaughton MPP Jeff Burch Office of Minister Peter Bethlenfalvy MPP Teresa Armstrong . -

CCAA Creditors List

ROSEBUD CREEK FINANCIAL CORP. AND 957855 ALBERTA LTD. Preliminary list of creditors as at June 17, 2020 as submitted by Rosebud Creek Financial Corp. and 957855 Alberta Ltd., (Unaudited) Creditor Address Amount due (CDN$)* #1 CONVENIENCE 924 EDMONTON TRAIL N.E. CALGARY AB T2E 3J9 3,306.39 #1 CONVENIENCE STORE 1 - 10015 OAKFIELD DR.S.W. CALGARY AB T2V 1S9 313.20 1178160 ALBERTA LTD. DEALER #3424 15416 BEAUMARIS ROAD EDMONTON AB T5X 4C1 1,364.04 12TH AVENUE PHARMACY 529 1192 - 101ST STREET NORTH BATTLEFORD SK S9A 0Z6 1,017.80 21 VARIETY BOX 729 PETROLIA ONN0N 1R0 1,498.12 2867-8118 QC INC (PJC 06 501 MONT ROYAL EST MONTREAL QC H2J 1W6 191.53 329985 ONTARIO LIMITED o/a KISKO PRODUCTS 50 ROYAL GROUP CRES, Unit 1 WOODBRIDGE ON L4H 1X9 44,357.47 3RD AVENUE MARKET 148 - 3 AVENUE WEST BOX 2382 MELVILLE SK S0A 2P0 613.72 407 ETR PO BOX 407, STN D SCARBOROUGH ONM1R 5J8 1,224.96 5 CORNERS CONVENIENCE 176 THE QUEENSWAY SOUTH KESWICK ON L4P 2A4 1,077.00 649 MEGA CONVENIENCE 5651 STEELES AVE E, UNIT 22 SCARBOROUGH ON M1V 5P6 853.72 7-ELEVEN CANADA INC 13450 102ND AVE, SUITE 2400 SURREY BC V3T 5X5 1,602.73 881 CORNER GAS BOX 360, 67165 LAKELAND DR LAC LA BICHE AB T0A 2C0 1,700.24 9334-3580 QUEBE 289 BOUL ST-JEAN POINTE CLAIRE QC H9R 3J1 15,964.29 957855 ALBERTA LTD. 120 SINNOTT ROAD SCARBOROUGH ON M1L 4N1 1,000,000.00 9666753 CANADA CORP. -

Waterfront Toronto Annual Report

June 28, 2018 Annual Report 2017/2018 2017/18 Annual Report / Contents Surveying by the Keating Channel. This work is related to the Cherry Street lakefilling project, part of the $1.25-billion Port Lands flood protection initiative, which began in December 2017. See pages 26-31 for more on this transformative project. 11 Vision 13 Message from the Chair 15 Message from the CEO 16 Who we are 17 Areas of focus 18 Our board 19 Committees and panels 21 Projects 24 What we achieved in 2017/18 26 The Port Lands 32 Complete Communities 36 Quayside 40 Public Places 44 Eastern Waterfront Transit 48 Financials 52 Capital investment 53 Capital funding 54 Corporate operating costs 55 Corporate capital costs 56 Resilience and risk management 59 Appendix I 63 Appendix 2 64 Executive team 2 3 Waterfront Toronto came together in 2001 to tackle big issues along the waterfront that only powerful collaboration across all three orders of government could solve. So far we’ve transformed over 690,000 square metres of land into active and welcoming public spaces that matter to Torontonians. A midsummer edition of Movies on the Common, a free public screening series at Corktown Common. The centrepiece of the emerging West Don Lands neighbourhood, Corktown Common is a 7.3-hectare Waterfront Toronto park that quickly became a beloved local gathering place after it opened in 2014. 4 5 Today, we’re creating a vibrant and connected waterfront that belongs to everyone. And we face one of the most exciting city- building opportunities on earth. -

PEO GOVERNMENT LIAISON PROGRAM Volume 13, 2019 GLP WEEKLY Issue 30 PEO OAKVILLE CHAPTER ATTENDS PC MPP COMMUNITY EVENT

September 27, PEO GOVERNMENT LIAISON PROGRAM Volume 13, 2019 GLP WEEKLY Issue 30 PEO OAKVILLE CHAPTER ATTENDS PC MPP COMMUNITY EVENT PEO Oakville Chapter GLP Co-coordinator Jeffrey Lee, P.Eng. (left), and Chapter Treasurer, Edward Gerges, P.Eng. (second to left), attended a community event on September 14 hosted by Effie Triantafilopoulos, MPP (Oakville–North Burlington), Parliamentary Assistant to the Minister of Long-Term Care (centre). Also in the photo is Peter Bethlenfalvy, MPP (Pickering— Uxbridge), President of the Treasury Board (second to right). For more on this story, see page 6. The GLP Weekly is published by the Professional Engineers of Ontario (PEO). Through the Professional Engineers Act, PEO governs over 89,000 licence and certificate holders, and regulates and advances engineering practice in Ontario to protect the public interest. Professional engineering safeguards life, health, property, economic interests, the public welfare and the environment. Past issues are available on the PEO Government Liaison Program (GLP) website at www.glp.peo.on.ca. To sign up to receive PEO’s GLP Weekly newsletter please email: [email protected]. *Deadline for submissions is the Thursday of the week prior to publication. The next issue will be published October 4. 1 | PAGE TOP STORIES THIS WEEK 1. PEO WINDSOR-ESSEX CHAPTER GLP CHAIR SPEAKS WITH NDP MPP AT A COMMUNITY EVENT 2. PEO EAST TORONTO CHAPTER ATTENDS PROJECT SPACES EVENT WITH NDP MPP 3. ENGINEERS PRESENTED WITH ONTARIO VOLUNTEER SERVICE AWARDS BY MPPS 4. NEW ONTARIO LEGISLATURE INTERNSHIP PROGRAMME INTERNS SELECTED FOR 2019/2020 5. PC AND NDP MPPs TO SPEAK AT PEO GLP ACADEMY AND CONGRESS ON OCTOBER 5 EVENTS WITH MPPs PEO WINDSOR-ESSEX CHAPTER GLP CHAIR SPEAKS WITH NDP MPP AT A COMMUNITY EVENT (WINDSOR) - PEO Windsor-Essex Chapter GLP Chair Asif Khan, P.Eng., had a chance to speak with NDP Community and Social Services Critic Lisa Gretzky, MPP (Windsor West), at a community event in Windsor on September 8. -

PEO GOVERNMENT LIAISON PROGRAM November 1, Volume 13, 2019 GLP WEEKLY Issue 34 PEO PRESIDENT & CEO/REGISTRAR MEET with ATTORNEY GENERAL

PEO GOVERNMENT LIAISON PROGRAM November 1, Volume 13, 2019 GLP WEEKLY Issue 34 PEO PRESIDENT & CEO/REGISTRAR MEET WITH ATTORNEY GENERAL PEO President Nancy Hill, P.Eng. (left), and CEO/Registrar Johnny Zuccon, P.Eng. (right), met with Attorney General Doug Downey, MPP (PC—Barrie—Springwater—Oro-Medonte) (centre), at his Queen’s Park office on October 29. For more on this story, see page 6. The GLP Weekly is published by the Professional Engineers of Ontario (PEO). Through the Professional Engineers Act, PEO governs over 89,000 licence and certificate holders, and regulates and advances engineering practice in Ontario to protect the public interest. Professional engineering safeguards life, health, property, economic interests, the public welfare and the environment. Past issues are available on the PEO Government Liaison Program (GLP) website at www.glp.peo.on.ca. To sign up to receive PEO’s GLP Weekly newsletter please email: [email protected]. *Deadline for submissions is the Thursday of the week prior to publication. The next issue will be published November 8. 1 | PAGE TOP STORIES THIS WEEK 1. PEO WEST TORONTO CHAPTER REPS PRESENTED WITH VOLUNTEER SERVICE AWARDS 2. PEO LAKE ONTARIO CHAPTER CHAIR MEETS PRESIDENT OF THE TREASURY BOARD 3. PEO PRESIDENT SPEAKS WITH MPPS AT TVO EVENT EVENTS WITH MPPs KINGSTON MPP TO SPEAK AT EASTERN REGION GLP ACADEMY AND CONGRESS ON NOVEMBER 23 Kingston will be the site of the PEO Eastern Ontario GLP Academy and Congress on November 23 (KINGSTON) - NDP Environment Critic Ian Arthur, MPP (Kingston & the Islands), has agreed to speak at the 2019 PEO Eastern Region GLP Academy in Kingston on November 23. -

2018 Ontario Candidates List May 8.Xlsx

Riding Ajax Joe Dickson ‐ @MPPJoeDickson Rod Phillips ‐ @RodPhillips01 Algoma ‐ Manitoulin Jib Turner ‐ @JibTurnerPC Michael Mantha ‐ @ M_Mantha Aurora ‐ Oak Ridges ‐ Richmond Hill Naheed Yaqubian ‐ @yaqubian Michael Parsa ‐ @MichaelParsa Barrie‐Innisfil Ann Hoggarth ‐ @AnnHoggarthMPP Andrea Khanjin ‐ @Andrea_Khanjin Pekka Reinio ‐ @BI_NDP Barrie ‐ Springwater ‐ Oro‐Medonte Jeff Kerk ‐ @jeffkerk Doug Downey ‐ @douglasdowney Bay of Quinte Robert Quaiff ‐ @RQuaiff Todd Smith ‐ @ToddSmithPC Joanne Belanger ‐ No social media. Beaches ‐ East York Arthur Potts ‐ @apottsBEY Sarah Mallo ‐ @sarah_mallo Rima Berns‐McGown ‐ @beyrima Brampton Centre Harjit Jaswal ‐ @harjitjaswal Sara Singh ‐ @SaraSinghNDP Brampton East Parminder Singh ‐ @parmindersingh Simmer Sandhu ‐ @simmer_sandhu Gurratan Singh ‐ @GurratanSingh Brampton North Harinder Malhi ‐ @Harindermalhi Brampton South Sukhwant Thethi ‐ @SukhwantThethi Prabmeet Sarkaria ‐ @PrabSarkaria Brampton West Vic Dhillon ‐ @VoteVicDhillon Amarjot Singh Sandhu ‐ @sandhuamarjot1 Brantford ‐ Brant Ruby Toor ‐ @RubyToor Will Bouma ‐ @WillBoumaBrant Alex Felsky ‐ @alexfelsky Bruce ‐ Grey ‐ Owen Sound Francesca Dobbyn ‐ @Francesca__ah_ Bill Walker ‐ @billwalkermpp Karen Gventer ‐ @KarenGventerNDP Burlington Eleanor McMahon ‐@EMcMahonBurl Jane McKenna ‐ @janemckennapc Cambridge Kathryn McGarry ‐ Kathryn_McGarry Belinda Karahalios ‐ @MrsBelindaK Marjorie Knight ‐ @KnightmjaKnight Carleton Theresa Qadri ‐ @TheresaQadri Goldie Ghamari ‐ @gghamari Chatham‐Kent ‐ Leamington Rick Nicholls ‐ @RickNichollsCKL Jordan -

Children and Youth in Care Day 2020: Political Engagement Summary

Children and Youth in Care Day 2020: Political Engagement Summary Total Engagement • 42 Members of Provincial Parliament • 18 Stakeholders PC Party Title Riding Doug Ford Premier (see video here) Etobicoke North Christine Elliott Deputy Premier, Minister of Health Newmarket—Aurora Todd Smith Minister of Children, Community and Social Bay of Quinte Services Jill Dunlop Associate Minister (see video here and news Simcoe North release here) Michael Tibollo Minister Without Portfolio Vaughan—Woodbridge Associate Minister of Mental Health and Addictions Michael Parsa Member, Standing Committee on Estimates Aurora—Oak Ridges—Richmond Hill Member, Standing Committee on Public Accounts Parliamentary Assistant to the President of the Treasury Board Vincent Ke Parliamentary Assistant to the Minister of Don Valley North Heritage, Sport, Tourism and Culture Industries (Culture and Sport) Lorne Coe Member, Standing Committee on Government Whitby Agencies Member, Standing Committee on Estimates Chief Government Whip Roman Baber Chair, Standing Committee on Justice Policy York Centre Goldie Ghamari Chair, Standing Committee on General Carleton Government Donna Skelly Member, Standing Committee on the Legislative Flamborough—Glanbrook Assembly Member, Standing Committee on Finance and Economic Affairs Parliamentary Assistant to the Minister of Economic Development, Job Creation and Trade (Job Creation and Trade) Bob Bailey Member, Standing Committee on General Sarnia—Lambton Government 2 | Ontario Association of Children’s Aid Societies Parliamentary -

GLP WEEKLY Issue 28 PEO LONDON CHAPTER PARTICIPATES in EVENT with THREE LOCAL NDP MPPS

September 13, PEO GOVERNMENT LIAISON PROGRAM Volume 13, 2019 GLP WEEKLY Issue 28 PEO LONDON CHAPTER PARTICIPATES IN EVENT WITH THREE LOCAL NDP MPPS PEO London Chapter GLP representative Raul Moraes, P. Eng., (left) and Chapter Vice-Chair Manish Dalal, P. Eng., (right) spoke with three London NDP MPPs: Peggy Sattler (London West) (centre right), Teresa Armstrong (London—Fanshawe) (centre left), and Terence Kernaghan (London North-Centre) (top) at a Labour Day event on September 2. The GLP Weekly is published by the Professional Engineers of Ontario (PEO). Through the Professional Engineers Act, PEO governs over 89,000 licence and certificate holders, and regulates and advances engineering practice in Ontario to protect the public interest. Professional engineering safeguards life, health, property, economic interests, the public welfare and the environment. Past issues are available on the PEO Government Liaison Program (GLP) website at www.glp.peo.on.ca. To sign up to receive PEO’s GLP Weekly newsletter please email: [email protected]. *Deadline for submissions is the Thursday of the week prior to publication. The next issue will be published September 20. 1 | PAGE TOP STORIES THIS WEEK 1. PEO SCARBOROUGH CHAPTER ATTENDS PC MPP BBQ 2. NDP DEPUTY LEADER AND MPP PARTICIPATES IN PEO BRAMPTON CHAPTER ANNUAL SUMMER EVENT 3. PEO YORK CHAPTER ENGINEERS MEET FORMER MPPS 4. PEO MISSISSAUGA CHAPTER PARTICIPATES IN EVENT WITH ASSOCIATE MINISTER AND FOUR OTHER MPPS EVENTS WITH MPPs PEO SCARBOROUGH CHAPTER ATTENDS PC MPP BBQ Aris Babikian, MPP (PC—Scarborough—Agincourt) (centre), meets PEO Scarborough Chapter GLP Chair Santosh Gupta, P.Eng. -

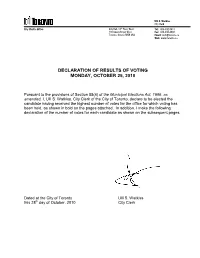

2010 Clerk's Official Declaration of Election Results

Ulli S. Watkiss City Clerk City Clerk’s Office City Hall, 13th Floor, West Tel: 416-392-8011 100 Queen Street West Fax: 416-392-4900 Toronto, Ontario M5H 2N2 Email: [email protected] Web: www.toronto.ca DECLARATION OF RESULTS OF VOTING MONDAY, OCTOBER 25, 2010 Pursuant to the provisions of Section 55(4) of the Municipal Elections Act, 1996, as amended, I, Ulli S. Watkiss, City Clerk of the City of Toronto, declare to be elected the candidate having received the highest number of votes for the office for which voting has been held, as shown in bold on the pages attached. In addition, I make the following declaration of the number of votes for each candidate as shown on the subsequent pages. Dated at the City of Toronto Ulli S. Watkiss this 28th day of October, 2010 City Clerk MAYOR CANDIDATE NAME VOTES ELECTED Rob Ford 383501 X George Smitherman 289832 Joe Pantalone 95482 Rocco Rossi 5012 George Babula 3273 Rocco Achampong 2805 Abdullah-Baquie Ghazi 2761 Michael Alexander 2470 Vijay Sarma 2264 Sarah Thomson 1883 Jaime Castillo 1874 Dewitt Lee 1699 Douglas Campbell 1428 Kevin Clarke 1411 Joseph Pampena 1319 David Epstein 1202 Monowar Hossain 1194 Michael Flie 1190 Don Andrews 1032 Weizhen Tang 890 Daniel Walker 804 Keith Cole 801 Michael Brausewetter 796 Barry Goodhead 740 Tibor Steinberger 735 Charlene Cottle 733 Christopher Ball 696 James Di Fiore 655 Diane Devenyi 629 John Letonja 592 Himy Syed 582 Carmen Macklin 575 Howard Gomberg 477 David Vallance 444 Mark State 438 Phil Taylor 429 Colin Magee 401 Selwyn Firth 394 Ratan Wadhwa 290 Gerald Derome 251 10/28/2010 Page 1 of 14 COUNCILLOR WARD NO.