Petroleum Import Infrastructure in Australia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CLYDE TERMINAL CONVERSION PROJECT APPENDIX D ECOLOGICAL ASSESSMENT Clyde Terminal Conversion Project the Shell Company of Australia Ltd 23-Aug-2013

CLYDE TERMINAL CONVERSION PROJECT APPENDIX D ECOLOGICAL ASSESSMENT Clyde Terminal Conversion Project The Shell Company of Australia Ltd 23-Aug-2013 Ecological Assessment Clyde Terminal Conversion Environmental Impact Statement AECOM Clyde Terminal Conversion Project Ecological Assessment Ecological Assessment Clyde Terminal Conversion Environmental Impact Statement Client: The Shell Company of Australia Ltd ABN: 46004610459 Prepared by AECOM Australia Pty Ltd Level 21, 420 George Street, Sydney NSW 2000, PO Box Q410, QVB Post Office NSW 1230, Australia T +61 2 8934 0000 F +61 2 8934 0001 www.aecom.com ABN 20 093 846 925 23-Aug-2013 Job No.: 60236231 AECOM in Australia and New Zealand is certified to the latest version of ISO9001, ISO14001, AS/NZS4801 and OHSAS18001. © AECOM Australia Pty Ltd (AECOM). All rights reserved. AECOM has prepared this document for the sole use of the Client and for a specific purpose, each as expressly stated in the document. No other party should rely on this document without the prior written consent of AECOM. AECOM undertakes no duty, nor accepts any responsibility, to any third party who may rely upon or use this document. This document has been prepared based on the Client’s description of its requirements and AECOM’s experience, having regard to assumptions that AECOM can reasonably be expected to make in accordance with sound professional principles. AECOM may also have relied upon information provided by the Client and other third parties to prepare this document, some of which may not have been verified. Subject to the above conditions, this document may be transmitted, reproduced or disseminated only in its entirety. -

The$Future$Of$ Clyde$Refinery$

SUBMISSION 9 - ATTACHMENT 2 THE$FUTURE$OF$ CLYDE$REFINERY$ Shell’s Clyde refinery: proposed closure and use as an import-only terminal A"report"to"CFMEU" Mining"&"Energy" and"AMWU" " July"2011" Strategic Economics and SGS Economics and Planning 2 $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ Any representation, statement, opinion or advice expressed or implied in this report is made in good faith but on the basis that Strategic Economics is not liable to any person for any damage or loss that has occurred or may occur in relation to that person taking or not taking action in respect of any representation, statement, opinion or advice referred to above. 3 Table of contents Preface 5 Executive Summary 6 1 Setting the scene 9 1.1 Background 9 1.2 Refinery economics 10 2 The Australian Refining Industry 13 2.1 Refinery participants location and capacity 13 2.2 Evolution of the Australian refining system 14 2.3 Current market structure 15 2.4 Supply and demand trends 15 2.5 The modest role of independent wholesalers 16 2.6 Recent processes of change in the structure of the retail market sector 18 2.7 Profitability of the petroleum refining industry 20 2.8 Profitability trends in the Australian wholesale and retail petroleum markets 22 2A Appendix The Caltex Window on the refining industry outlook in Australia 24 3 Clyde Refinery 31 3.1 Overview 31 3.2 NSW transport fuels and infrastructure hub 33 3.3 Access to growing markets 33 3.4 Flexibility 34 3.5 Skilled workforce 35 3.6 Complementary industries 35 3.7 Challenges -

United Petroleum Retail Fuel Outlets Compliance Activity Outcomes

United Petroleum retail fuel outlets: Summary of compliance activity outcomes April 2017 © Commonwealth of Australia 2017 Background The Fair Work Ombudsman (FWO) and its predecessor agencies have received a number of requests for assistance from United Petroleum franchise and commission agent employees. On 3 September 2015, a media article was published containing allegations United Petroleum employees were underpaid minimum hourly rates, in some cases receiving as low as $10 an hour. These allegations were consistent with the pattern of requests for assistance received by the FWO, and as a result, a broader compliance activity (the Activity) was undertaken to assess United Petroleum retail fuel outlets compliance with Commonwealth workplace laws. Consistent with other significant compliance activities involving franchise networks, the Activity assessed the levels of compliance by United Petroleum, its associated entities, franchisees and commission agents. During the Activity, United Petroleum operated a 100% franchise and commission agent model. Approximately 40 of their 440 outlets were franchised and the remainder operated as commission agents. However United Petroleum has since informed the FWO of its intention to move away from a franchise model and operate stores through commission agents, the company directly or on a supply-only basis in the future. United Petroleum [ACN 085 779 255] is based in Abbotsford Victoria, and is an Australian owned proprietary company first registered in 1999. United Petroleum does not operate any retail fuel sites itself and does not directly enter into the franchise or commission agent agreements. That role is performed by United Petroleum Franchise [ACN 127 764 989], an associated entity also based in Abbotsford. -

2017 Biofuels Annual Australia

THIS REPORT CONTAINS ASSESSMENTS OF COMMODITY AND TRADE ISSUES MADE BY USDA STAFF AND NOT NECESSARILY STATEMENTS OF OFFICIAL U.S. GOVERNMENT POLICY Required Report - public distribution Date: 8/15/2017 GAIN Report Number: AS1712 Australia Biofuels Annual 2017 Approved By: Sarah Hanson, Agricultural Counselor Prepared By: Roger Farrell, Agricultural Specialist Report Highlights: The Australian biofuel industry and market remain small because mandates do not cover the entire country and remain modest compared to other countries with biofuel programs, and tax relief alone has not boosted biofuel use. With minimal mandate support, biodiesel production and imports have collapsed since 2014 due to lower world crude oil prices and high feedstock prices. Total biofuel production for 2017 is estimated at 290 million liters (ML), comprised of 250 million ML of fuel ethanol and a sharply reduced 40 million ML of biodiesel. Production of fuel ethanol has declined less (just over 15 percent since 2013) because of its value as an oxygenate in gasoline, and it is supported by a mandate in New South Wales (NSW) and a new 2017 mandate in Queensland. Second-generation biofuels, such as energy crops and algae-based fuels, have been successfully tested but are not yet commercially viable. However, the Queensland government has provided support for an advanced biofuels plant to produce fuel for military, aviation and marine applications. Post: Canberra I EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Australia is a major importer of crude oil and refined products for transport fuels; although overall it is a leading international exporter of energy. There has been a continued decline in domestic refining capacity for transport fuels and a significant rise in import dependence, with 85 per cent of refinery feedstock and 45 per cent of refined production consumption now met from imports. -

Public Hearing Transcript Tuesday 5 May 2020 Litchfield Room

LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY OF THE NORTHERN TERRITORY 13th Assembly PUBLIC ACCOUNTS COMMITTEE Public Hearing Transcript Tuesday 5 May 2020 Litchfield Room Members: Mrs Kate Worden MLA, Chair, Member for Sanderson Mr Gerry Wood MLA, Member for Nelson Mr Terry Mills MLA, Deputy Chair, Member for Blain Mr Tony Sievers MLA, Member for Brennan Mr Gary Higgins MLA, Member for Daly (via videoconference) Witnesses: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission Mr Matthew Schroder, General Manager, Infrastructure and Transport – Access and Pricing Mr Gary Dobinson, Director, Fuel Prices and Market Analysis Automobile Association of the Northern Territory Mr Anthony Hill, Chief Executive Officer Mr Edon Bell, Senior Manager – Operations Puma Energy Australia Mr Steve Niebling, Fuel Pricing Manager Mr Alan Plews, General Manager – Retail Mr Mark McKenzie, Chief Executive Officer, Australasian Convenience and Petroleum Marketers Association United Petroleum PTY LTD Mr David Szymczak, Chief Operating Officer Viva Energy Ms Megan Foster, Executive General Manager, Consumer Ms Edwina Pribyl, Head of External Communications FuelXpress Mr Mark McKenzie, Chief Executive Officer, Australasian Convenience and Petroleum Marketers Association Vopak Mr Mark Haggerty, Commercial and Business Development Manager Mr Fulco van Geuns, Managing Director Mr Paul Birch, Terminal Manager, Darwin Caltex Australia Mr Prasad Kholkute, Head of Retail Pricing Mr Todd Loydell, Head of Government Affairs Public Accounts Committee – Tuesday 5 May 2020 The committee convened at 9.00 am. PUBLIC HEARING ON NORTHERN TERRITORY FUEL PRICES Australian Competition and Consumer Commission Madam CHAIR: On behalf of the committee I welcome everyone to this public hearing into Northern Territory fuel prices. I welcome to the table to give evidence to the committee Mr Matthew Schroder, General Manager, Infrastructure and Transport - Access and Pricing from the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission. -

World Oil Outlook 2012

World Oil Outlook 2012 Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries The data, analysis and any other information (‘Content’) contained in this publication is for infor- mational purposes only and is not intended as a substitute for advice from your business, finance, investment consultant or other professional. Whilst reasonable efforts have been made to ensure the accuracy of the Content of this publication, the OPEC Secretariat makes no warranties or represen- tations as to its accuracy, currency or comprehensiveness and assumes no liability or responsibility for any error or omission and/or for any loss arising in connection with or attributable to any action or decision taken as a result of using or relying on the Content of this publication. This publication may contain references to material(s) from third parties whose copyright must be acknowledged by obtaining necessary authorization from the copyright owner(s). The OPEC Secretariat will not be liable or responsible for any unauthorized use of third party material(s). The views expressed in this publication are those of the OPEC Secretariat and do not necessarily reflect the views of individual OPEC Member Countries. The material contained in this publication may be used and/or reproduced for educational and other non-commercial purposes without prior written permission from the OPEC Secretariat provided that the copyright holder is fully acknowledged. © OPEC Secretariat, 2012 Helferstorferstrasse 17 A-1010 Vienna, Austria www.opec.org ISBN 978-3-9502722-4-6 4 OPEC is a permanent, intergovernmental organization, established in Baghdad, Iraq, 10–14 September 1960. The Organization comprises 12 Members: Algeria, Angola, Ecuador, Islamic Republic of Iran, Iraq, Kuwait, Libya, Nigeria, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, United Arab Emirates and Venezuela. -

Monitoring of the Australian Petroleum Industry

Monitoring of the Australian petroleum industry: Monitoring of the Australian petroleum Report of the ACCC into the prices, costs and prots of unleaded petrol in Australia of unleaded petrol Report of the ACCC into prices, costs and prots Monitoring of the Australian petroleum industry Report of the ACCC into the prices, costs and prots of unleaded petrol in Australia DECEMBER 2009 www.accc.gov.au December 2009 Monitoring of the Australian petroleum industry Report of the ACCC into the prices, costs and profi ts of unleaded petrol in Australia DECEMBER 2009 Australian Competition and Consumer Commission 23 Marcus Clarke Street, Canberra, Australian Capital Territory 2601 First published by the ACCC 2009 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 © Commonwealth of Australia 2009 This work is copyright. Apart from any use permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced without prior written permission from the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission. Requests and inquiries concerning reproduction and rights should be addressed to the Director Publishing, ACCC, GPO Box 3131, Canberra ACT 2601, or [email protected]. Important notice The information in this publication is for general guidance only. It does not constitute legal or other professional advice, and should not be relied on as a statement of the law in any jurisdiction. Because it is intended only as a general guide, it may contain generalisations. You should obtain professional advice if you have any specifi c concern. The ACCC has made every reasonable effort to provide current and accurate information, but it does not make any guarantees regarding the accuracy, currency or completeness of that information. -

Australian Refining – Issues Paper

SUBMISSION 18 SUBMISSION 18 SUBMISSION 18 Department of Resources, Energy and Tourism Submission to the Parliamentary Inquiry into Australia’s Oil Refinery Industry 23 November 2012 SUBMISSION 18 Contents 1. Introduction.............................................................................................2 2. Background.............................................................................................3 2.1. Overview of the liquid fuels sector .......................................................3 2.2. The Australian Refining Sector .............................................................5 2.2.1. History of the Sector ......................................................................6 2.2.2. Current Capacity and Production .................................................7 3. Terms of Reference 1 - International and Domestic Trends and Pressures .......................................................................................................9 3.1. Australian refining capacity in Regional and Global Context ........9 3.2. Liquid fuel demand by region .........................................................10 3.3. Capacity expansion in Asia and the Middle East ..........................11 3.4. Pressures on Refining Globally ......................................................11 3.5. Competitive pressures on OECD Refineries..................................12 3.6. Competitive pressures on Australian Refineries...........................13 4. Terms of Reference 2 – Impact of Declining Refinery Capacity in -

Australian Petroleum Exploration Association Limited Members of the Professional Division

AUSTRALIAN PETROLEUM EXPLORATION ASSOCIATION LIMITED MEMBERS OF THE PROFESSIONAL DIVISION New South Wales Nate Affiliation Name Affiliation Nand Affiliation D. Esso Abbott. Earl O. Continental Gerrard. M. J. Beaver McEvoy. McGarry. D. 1. Australian Oil & Gas Agnew. J. D. Inter. Oil & Minerals Ins. Gidley. P. R. McGee. J. B. Arco Andrejewskis. A. J. Ampol Glucksnrann. D. A. G. H. Andresen. Finn Target Goddard. G. G. Zapata McIntosh. McKay. B. G. Esso Angus. A. L Macdonald. Wagner & Priddle Graham. Miss B. McWilliams, F. W. Continental Armstrobng. R. A. Burmah Graham. T. APEA Mahoney. M. J. Auchincloss. G. Greases. S. R. Manhoff, C. N. Esso Bain. J. S. Esso Grand. R. B. Continental J. Marshall, A. J. Pacmines Barr. J. R. Garrett Lance & Co. Guest. D. W. J. & North Consultants Matzkows. A. L. PI B Bartlett. R. J. Esso Hackfonh-Jones. Paul BCA Management Maughan. D. M. Esso Beddoes. L. R.. Jnr. Hall, H. E Burmah Maxwell. W. G. H. Appraisals Mining & Geological Bein. J. Esso Hall. J. R. Aust. Groundwater Consultants Melzer, A. D. Tricentrol Bichan. H. K. Robertson Research Hall. P. C. Esso Meyer, R. R. Bros Biggers. G. C. Esso Hall. R. G. William Meyers. N. A. Birmingham. P. J. Esso Hall. R. K. Oil Drilling & Exploration Milne. N. F. Burmah Black. J. R. Faso Hammaa. H. R. Ayrshire Exploration Miskelly. N. Ord. Minnest. T. J. Thompson & Ptnrs Blau. E_ J. Burmah Hancock. R. A. W. Es so Blanden. I. D. Esso Harrington. H. J. University of New England Moffett. A. Blunter. J. M. Beaver Harris, A. G. Bridge Montano, R. -

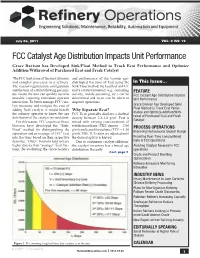

FCC Catalyst Age Distribution Impacts Unit Performance

July 06, 2011 VOL: 2 ISS: 12 FCC Catalyst Age Distribution Impacts Unit Performance Grace Davison has Developed Sink/Float Method to Track Ecat Performance and Optimize Addition/Withrawal of Purchased Ecat and Fresh Catalyst The FCC unit is one of the most dynamic and performance of the various age- and complex processes in a refinery. distributed fractions of Ecat using the In This Issue... The reactor-regeneration configuration Sink/Float method, the health of an FCC and the tons of catalyst flowing per min- unit’s catalyst inventory (e.g., remaining FEATURE ute means the unit can quickly become activity, metals poisoning, etc.) can be FCC Catalyst Age Distribution Impacts unstable, requiring immediate operator determined and steps can be taken to Unit Performance interaction. To better manage FCC cata- improve operations. lyst inventory and mitigate the cost of Grace Davison has Developed Sink/ adding fresh catalyst, it would benefit Float Method to Track Ecat Perfor- Why Separate Ecat? mance and Optimize Addition/With- the refinery operator to know the age FCC Ecat generally displays a skeletal rawal of Purchased Ecat and Fresh distribution of the catalyst in circulation. density between 2.4-2.8 g/ml. Ecat is Catalyst For this reason, FCC experts at Grace mixed with varying concentrations of Davison have developed the “Sink/ tetrabromoethane (TBE density = 2.96 PROCESS OPERATIONS Float” method for distinguishing the g/ml) and tetrachloroethane (TCE = 1.58 Improving Hydrocracker Quench Design separation and percentage of FCC Ecat g/ml). TBE:TCE ratios are adjusted until into fractions based on their respective the desired split is achieved. -

Weekly Construction Law Review Selected from Our Daily Bulletins Covering Construction

Friday, 21 February 2020 Weekly Construction Law Review Selected from our Daily Bulletins covering Construction Search Engine Click here to access our search engine facility to search legal issues, case names, courts and judges. Simply type in a keyword or phrase and all relevant cases that we have reported in Benchmark since its inception in June 2007 will be available with links to each case. Executive Summary (1 minute read) Commissioner of Taxation v Scone Race Club Limited (FCAFC) - superannuation - taxation - employment - respondent not liable to pay 'superannuation guarantee charge' to jockeys - appeal dismissed Australian Broadcasting Corporation v Kane (No 2) (FCA) - administrative law - constitutional law - criminal law - applicant challenged warrant issued to Agent of Australian Federal Police under s3E Crimes Act 1914 (Cth) - application dismissed Super Vision Resources Ltd v AC Holdings Co Pty Ltd (NSWSC) - conveyancing - plaintiff sought to set aside second defendant’s sale of properties to first defendant under s37A Conveyancing Act 1919 (NSW) - proceedings dismissed United Petroleum Australia Pty Ltd v Herbert Smith Freehills (VSCA) - retainer - solicitors' costs - costs - indemnity costs - leave to appeal in respect of 'fees proceeding' refused - appeals against costs orders dismissed Australia Pacific LNG Pty Limited & Ors v The Treasurer, Minister for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Partnerships and Minister for Sport (QCA) - administrative law - refusal to grant declaration that Minister had adopted method of -

Petroleum Products

INDUSTRY COMMISSION Petroleum Products REPORT NO. 40 5 July 1994 Australian Government Printing Service Melbourne TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ABBREVIATIONS X GLOSSARY XIII TERMS OF REFERENCE XV PART A: OVERVIEW XVII FINDINGS AND RECOMMENDATIONS XLII PART B: 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS v PART A: v PART B: v 1v 3 INDUSTRY PERFORMANCE 21 vi V PETROLEUM PRODUCTS 6 PRICES OVERSIGHT AND COMPETITION 107 vii 10 ENVIRONMENTAL CONSIDERATIONS 199 ix 11 TRANSPORT 227 ix 12 TEMPERATURE CORRECTION 243 ix 13 TAXES AND CHARGES 251 x PART C: xi APPENDICES xi REFERENCES xi ABBREVIATIONS xii GLOSSARY xv TERMS OF REFERENCE xvii TABLE OF CONTENTS v PART A: v PART B: v 1v 3 INDUSTRY PERFORMANCE 21 vi 6 PRICES OVERSIGHT AND COMPETITION 107 vii 10 ENVIRONMENTAL CONSIDERATIONS 199 ix 11 TRANSPORT 227 ix 12 TEMPERATURE CORRECTION 243 ix 13 TAXES AND CHARGES 251 x PART C: xi APPENDICES xi REFERENCES xi ABBREVIATIONS xii GLOSSARY xv TERMS OF REFERENCE xvii 3 INDUSTRY PERFORMANCE 21 3.1 Use of capital 21 3.2 Use of labour 29 3.3 General indications of performance 36 3.4 Conclusion 46 TABLE OF CONTENTS v PART A: v VI PART B: v 1v 3 INDUSTRY PERFORMANCE 21 vi 6 PRICES OVERSIGHT AND COMPETITION 107 vii 10 ENVIRONMENTAL CONSIDERATIONS 199 ix 11 TRANSPORT 227 ix 12 TEMPERATURE CORRECTION 243 ix 13 TAXES AND CHARGES 251 x PART C: xi APPENDICES xi REFERENCES xi ABBREVIATIONS xii GLOSSARY xv TERMS OF REFERENCE xvii TABLE OF CONTENTS v PART A: v PART B: v 1v 3 INDUSTRY PERFORMANCE 21 vi 6 PRICES OVERSIGHT AND COMPETITION 107 vii 10 ENVIRONMENTAL CONSIDERATIONS 199 ix 11 TRANSPORT 227