Fde776c218b0de52042fd92ccd1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Battle with Grendel

That Herot would be his to command. And then He declared: 385 ' "No one strange to this land Has ever been granted what I've given you, No one in all the years of my rule. Make this best of all mead-halls yours, and then Keep it free of evil, fight 390 With glory in your heart! Purge Herot And your ship will sail home with its treasure-holds full." . The feast ends. Beowulf and his men take the place of Hrothgar's followers and lie down to sleep in Herot. Beowulf, however, is wakeful, eager to meet his enemy. The Battle with Grendel 8 Out from the marsh, from the foot of misty Hills and bogs, bearing God's hatred, Grendel came, hoping to kill 395 Anyone he could trap on this trip to high Herot. He moved quickly through the cloudy night, Up from his swampland, sliding silently Toward that gold-shining hall. He had visited Hrothgar's Home before, knew the way— 4oo But never, before nor after that night, Found Herot defended so firmly, his reception So harsh. He journeyed, forever joyless, Bronze coin showing a Straight to the door, then snapped it open, warrior killing a monster. Tore its iron fasteners with a touch, 405 And rushed angrily over the threshold. He strode quickly across the inlaid Floor, snarling and fierce: His eyes Gleamed in the darkness, burned with a gruesomeX Light. Then he stopped, seeing the hall 4io Crowded with sleeping warriors, stuffed With rows of young soldiers resting together. And his heart laughed, he relished the sight, Intended to tear the life from those bodies By morning; the monster's mind was hot 415 With the thought of food and the feasting his belly Would soon know. -

Hollywood North Rising Star Nicole Laplaca

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Hollywood North Rising Star Nicole LaPlaca Vancouver, October 20, 2013 - Canadian-born Nicole LaPlaca is one of Hollywood North’s brightest rising stars. The Leo Award-nominated actress received the accolade in 2004 for her performance in the short film Beachbound. Nicole most recently appeared on screen in the Lifetime television movie Secret Liaison co-starring Meredith Monroe. She can also be seen on City TV in an episode of the sitcom Package Deal ("Kim vs. Karaoke") and has just wrapped a guest appearance on Steven Spielberg’s popular sci-fi tv series Falling Skies, episode 1, season 4, set to air next summer. Audiences will recognize Nicole from her most notable role as Natalia in the hit Warner Brothers film Another Cinderella Story, in which she starred alongside Selena Gomez and Jane Lynch. According to Nicole, one of her favorite things about inhabiting that character was that she found it "exhilarating to play the enemy.” She says her dream role would be the character of “Deb” from the Showcase series Dexter because “she’s so raw and unpredictable.” Nicole hopes to one day work with renowned film director Martin Scorsese. Nicole made her industry debut at the age of 9, after following in her sister Jennifer's footsteps. She has appeared in over 40 professional projects to-date, with numerous guest and supporting roles in television shows, films, commercials and stage productions including: Falling Skies, Package Deal, Alcatraz, Supernatural, American Dreams, Stephen King's The Dead Zone and End Game. In addition to Another Cinderella Story and Secret Liaison, her other film credits include John Tucker Must Die, Mount Pleasant and The Lizzie McGuire Movie. -

Organisms and Human Bodies As Contagions in the Post-Apocalyptic State

CHAPTER 1 Organisms and Human Bodies as Contagions in the Post-Apocalyptic State Robert A. Booth n this chapter, I show how discourses of contagion and pollution not only imbue many post-apocalyptic cinema and television narratives but also mirror public discourse about immigration. Further, I examine the often- I 1 racialized immigrant in post-apocalyptic film and television that is, in essence, a discourse on insider–outsider social divisions and relationships of power. Finally, I elucidate the argument that post-apocalyptic film and television rein- force the primacy of centralized political authority, namely the State, and post- 9/11 post-apocalyptic film in particular reinforces the hegemony of the State. The post-apocalyptic subgenre of science fiction and/or horror has become popular fodder for cinema and television. As Susan Sontag notes, “the science fiction film . is concerned with the aesthetics of destruction, with the pecu- liar beauties to be found in wreaking havoc, making a mess. And it is in the imagery of destruction that the core of a good science fiction film lies.”2 Portrayals of the post-apocalypse often index or echo visual memories of terrible societal traumatic events of the past.3 With the experience of the social, political, economic, and emotional trauma of the 9/11 attacks, one might reasonably assume that Americans would acquire a distaste for graphic destructive violence. Certainly, after the attacks, filmmakers occasionally felt pressured to remove images of the Twin Towers or to change content that might evoke the tragedy, such as planes crashing into skyscrapers. However, post-apocalyptic genres remain ever popular in American television and cinema. -

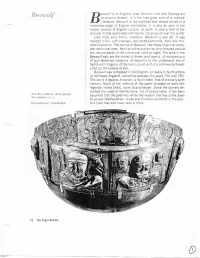

Beowulf to Ancient Greece: It Is T^E First Great Work of a Nationai Literature

\eowulf is to England what Hcmer's ///ac/ and Odyssey are Beowulf to ancient Greece: it is t^e first great work of a nationai literature. Becwulf is the mythical and literary record of a formative stage of English civilization; it is also an epic of the heroic sources of English cuitu-e. As such, it uses a host of tra- ditional motifs associated with heroic literature all over the world. Liks most early heroic literature. Beowulf is oral art. it was hanaes down, with changes, and embe'lishrnents. from one min- strel to another. The stories of Beowulf, like those of all oral epics, are traditional ones, familiar to tne audiences who crowded around the harp:st-bards in the communal halls at night. The tales in the Beowulf epic are the stories of dream and legend, of monsters and of god-fashioned weapons, of descents to the underworld and of fights with dragons, of the hero's quest and of a community threat- ened by the powers of evil. Beowulf was composed in Old English, probably in Northumbria in northeast England, sometime between the years 700 and 750. The world it depicts, however, is much older, that of the early sixth century. Much of the material of the poem is based on early folk legends—some Celtic, some Scandinavian. Since the scenery de- scribes tne coast of Northumbna. not of Scandinavia, it has been A Celtic caldron. MKer-plateci assumed that the poet who wrote the version that has come down i Nl ccnlun, B.C.). to us was Northumbrian. -

An Examination of Scandinavian War Cults in Medieval Narratives of Northwestern Europe from the Late Antiquity to the Middle Ages

PETTIT, MATTHEW JOSEPH, M.A. Removing the Christian Mask: An Examination of Scandinavian War Cults in Medieval Narratives of Northwestern Europe From the Late Antiquity to the Middle Ages. (2008) Directed by Dr. Amy Vines. 85 pp. The aim of this thesis is to de-center Christianity from medieval scholarship in a study of canonized northwestern European war narratives from the late antiquity to the late Middle Ages by unraveling three complex theological frameworks interweaved with Scandinavian polytheistic beliefs. These frameworks are presented in three chapters concerning warrior cults, war rituals, and battle iconography. Beowulf, The History of the Kings of Britain, and additional passages from The Wanderer and The Dream of the Rood are recognized as the primary texts in the study with supporting evidence from An Ecclesiastical History of the English People, eighth-century eddaic poetry, thirteenth- century Icelandic and Nordic sagas, and Le Morte d’Arthur. The study consistently found that it is necessary to alter current pedagogical habits in order to better develop the study of theology in medieval literature by avoiding the conciliatory practice of reading for Christian hegemony. REMOVING THE CHRISTIAN MASK: AN EXAMINATION OF SCANDINAVIAN WAR CULTS IN MEDIEVAL NARRATIVES OF NORTHWESTERN EUROPE FROM THE LATE ANTIQUITY TO THE MIDDLE AGES by Matthew Joseph Pettit A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of The Graduate School at The University of North Carolina at Greensboro in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts Greensboro 2008 Approved by ______________________________ Committee Chair APPROVAL PAGE This thesis has been approved by the following committee of the Faculty of The Graduate School at The University of North Carolina at Greensboro. -

Introduction the Waste-Ern Literary Canon in the Waste-Ern Tradition

Notes Introduction The Waste-ern Literary Canon in the Waste-ern Tradition 1 . Zygmunt Bauman, Wasted Lives: Modernity and Its Outcasts (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2004), 26. 2 . M a r y D o u g las, Purity and Danger: An Analysis of the Concepts of Pollution and Taboo (London: Routledge, 1966/2002), 2, 44. 3 . S usan Signe Morrison, E xcrement in the Late Middle Ages: Sacred Filth and Chaucer’s Fecopoeticss (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2008), 153–158. The book enacts what Dana Phillips labels “excremental ecocriticism.” “Excremental Ecocriticism and the Global Sanitation Crisis,” in M aterial Ecocriticism , ed. Serenella Iovino and Serpil Oppermann (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2014), 184. 4 . M o r r i s o n , Excrementt , 123. 5 . Dana Phillips and Heather I. Sullivan, “Material Ecocriticism: Dirt, Waste, Bodies, Food, and Other Matter,” Interdisci plinary Studies in Literature and Environment 19.3 (Summer 2012): 447. “Our trash is not ‘away’ in landfills but generating lively streams of chemicals and volatile winds of methane as we speak.” Jane Bennett, Vibrant Matter: A Political Ecology of Things (Durham: Duke University Press, 2010), vii. 6 . B e n n e t t , Vibrant Matterr , viii. 7 . I b i d . , vii. 8 . S e e F i gures 1 and 2 in Vincent B. Leitch, Literary Criticism in the 21st Century: Theory Renaissancee (London: Bloomsbury, 2014). 9 . Pippa Marland and John Parham, “Remaindering: The Material Ecology of Junk and Composting,” Green Letters: Studies in Ecocriticism 18.1 (2014): 1. 1 0 . S c o t t S lovic, “Editor’s Note,” Interdisciplinary Studies in Literature and Environment 20.3 (2013): 456. -

The Herodotos Project (OSU-Ugent): Studies in Ancient Ethnography

Faculty of Literature and Philosophy Julie Boeten The Herodotos Project (OSU-UGent): Studies in Ancient Ethnography Barbarians in Strabo’s ‘Geography’ (Abii-Ionians) With a case-study: the Cappadocians Master thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master in Linguistics and Literature, Greek and Latin. 2015 Promotor: Prof. Dr. Mark Janse UGent Department of Greek Linguistics Co-Promotores: Prof. Brian Joseph Ohio State University Dr. Christopher Brown Ohio State University ACKNOWLEDGMENT In this acknowledgment I would like to thank everybody who has in some way been a part of this master thesis. First and foremost I want to thank my promotor Prof. Janse for giving me the opportunity to write my thesis in the context of the Herodotos Project, and for giving me suggestions and answering my questions. I am also grateful to Prof. Joseph and Dr. Brown, who have given Anke and me the chance to be a part of the Herodotos Project and who have consented into being our co- promotores. On a whole other level I wish to express my thanks to my parents, without whom I would not have been able to study at all. They have also supported me throughout the writing process and have read parts of the draft. Finally, I would also like to thank Kenneth, for being there for me and for correcting some passages of the thesis. Julie Boeten NEDERLANDSE SAMENVATTING Deze scriptie is geschreven in het kader van het Herodotos Project, een onderneming van de Ohio State University in samenwerking met UGent. De doelstelling van het project is het aanleggen van een databank met alle volkeren die gekend waren in de oudheid. -

The Middle Ages. 449- 1485 Life and Culture • Middle Ages Is the Period of Time

The Middle Ages 449-1485 The Middle Ages The Middle Ages. 449- 1485 Life and culture • Middle Ages is the period of time Art that extends between the ancient classical period and the Language history Renaissance • Middle Ages extends from the The spread of Christianity Roman withdrawal and the Anglo Saxon invasion in 5th century to the accession of the House of Tudor in Beowulf th the late 15 century 1 Maspa Sadari The Middle Ages 449-1485 The Middle Ages The earlier part of this period is called The dark Ages • Middle Ages is divided in two parts: the first is named Anglo Saxon Period or Old English Period (449-1066); the second is named the Anglo Norman Period or Middle English period (1066- 1485) 2 Maspa Sadari The Middle Ages 449-1485 Anglo Saxon or Old English period (449-1066) • In 449 the tribes of Jutes, angles and Saxons from Denmark and Northern Germany started to invade Britain defeating original Celtic people who escaped to Cornwall, Wales and Scotland. 3 Maspa Sadari The Middle Ages 449-1485 The language of these tribes was the Anglo- Saxon • The country was divided into 7 kingdoms, which soon had to face Viking invasions. The joined the forces and managed to defeat Vikings 4 Maspa Sadari The Middle Ages 449-1485 Life and culture • Life in Saxon England: society was based on the family unit, the clan, the tribe • The code of values was based on courage, loyalty to the ruler, generosity. The most important hero in a poem of this period is Beowulf 5 Maspa Sadari The Middle Ages 449-1485 The culture was military, based on war -

Medievalism and the Shocks of Modernity: Rewriting Northern Legend from Darwin to World War II

Medievalism and the Shocks of Modernity: Rewriting Northern Legend from Darwin to World War II by Dustin Geeraert A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies of The University of Manitoba In partial fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of English, Film, and Theatre University of Manitoba Winnipeg Copyright © 2016 by Dustin Geeraert 1 Abstract Literary medievalism has always been critically controversial; at various times it has been dismissed as reactionary or escapist. This survey of major medievalist writers from America, England, Ireland and Iceland aims to demonstrate instead that medievalism is one of the characteristic literatures of modernity. Whereas realist fiction focuses on typical, plausible or common experiences of modernity, medievalist literature is anything but reactionary, for it focuses on the intellectual circumstances of modernity. Events such as the Enlightenment, the Industrial Revolution, many political revolutions, the world wars, and the scientific discoveries of Isaac Newton (1643-1727) and above all those of Charles Darwin (1809-1882), each sent out cultural shockwaves that changed western beliefs about the nature of humanity and the world. Although evolutionary ideas remain controversial in the humanities, their importance has not been lost on medievalist writers. Thus, intellectual anachronisms pervade medievalist literature, from its Romantic roots to its postwar explosion in popularity, as some of the greatest writers of modern times offer new perspectives on old legends. The first chapter of this study focuses on the impact of Darwin’s ideas on Victorian epic poems, particularly accounts of natural evolution and supernatural creation. The second chapter describes how late Victorian medievalists, abandoning primitivism and claims to historicity, pushed beyond the form of the retelling by simulating medieval literary genres. -

Tolkien's Creative Technique: <I>Beowulf</I> and <I>The Hobbit</I>

Volume 15 Number 3 Article 1 Spring 3-15-1989 Tolkien's Creative Technique: Beowulf and The Hobbit Bonniejean Christensen Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore Part of the Children's and Young Adult Literature Commons Recommended Citation Christensen, Bonniejean (1989) "Tolkien's Creative Technique: Beowulf and The Hobbit," Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature: Vol. 15 : No. 3 , Article 1. Available at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore/vol15/iss3/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Mythopoeic Society at SWOSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature by an authorized editor of SWOSU Digital Commons. An ADA compliant document is available upon request. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To join the Mythopoeic Society go to: http://www.mythsoc.org/join.htm Mythcon 51: A VIRTUAL “HALFLING” MYTHCON July 31 - August 1, 2021 (Saturday and Sunday) http://www.mythsoc.org/mythcon/mythcon-51.htm Mythcon 52: The Mythic, the Fantastic, and the Alien Albuquerque, New Mexico; July 29 - August 1, 2022 http://www.mythsoc.org/mythcon/mythcon-52.htm Abstract Asserts that “The Hobbit, differing greatly in tone, is nonetheless a retelling of the incidents that comprise the plot and the digressions in both parts of Beowulf.” However, his retelling is from a Christian point of view. Additional Keywords Beowulf—Influence on The Hobbit; olkien,T J.R.R. -

Cgpt1; MAGNA GERMANIA; CLAUDIUS PTOLEMY BOOK 2, CHAPTER 10; FACT OR FICTION

cgPt1; MAGNA GERMANIA; CLAUDIUS PTOLEMY BOOK 2, CHAPTER 10; FACT OR FICTION SYNOPSIS The locations of some +8000 settlements and geographical features are included within the text of Claudius Ptolemy‟s „Geographia‟. To control the text and ensure readers understood the methodology there-in utilised it is evident that Claudius Ptolemy determined a strict order and utilisation of the information he wished to disseminate. That strict methodology is maintained through the first 9 chapters of Book 2, but the 10th chapter breaks all of the rules that had been established. Chapters 11 to 15 then return to the established pattern. Magna Germania was basically unknown territory and in such a situation Claudius Ptolemy was able to ignore any necessity to guess thus leaving an empty landscape as is evinced in Book 3, chapter 5, Sarmatian Europe. Why in an unknown land there are 94 settlements indicated in Germania when the 3 provinces of Gallia have only a total of 114 settlements, is a mystery? And, why does Claudius Ptolemy not attribute a single settlement to a tribal group? It appears there are other factors at play, which require to be investigated. BASIC PTOLEMY When analysing a map drawn from the data provided by Claudius Ptolemy it is first necessary to ensure that it is segregated into categories. Those are; 1) reliable information i.e. probably provided via the Roman Army Cosmographers and Geometres; 2) the former information confirmed or augmented by various itineraries or from Bematists; 3) the possibility of latitudinal measurements from various settlements (gnomon ratios); 4) basic travellers tales with confirmed distances „a pied‟; 5) basic sailing distances along coastlines and those which can be matched to land distances; 6) guesses made by travellers who did not actually record the days travelled but only the length of time for the overall journey; 7) obscure references from ancient texts which cannot be corroborated. -

06 7-26-11 TV Guide.Indd

Page 6 THE NORTON TELEGRAM Tuesday, July 26, 2011 Monday Evening August 1, 2011 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 KHGI/ABC The Bachelorette The Bachelorette Local Nightline Jimmy Kimmel Live WEEK OF FRIDAY , JULY 29 THROUGH THURSDAY , AUG . 4 KBSH/CBS How I Met Mike Two Men Mike Hawaii Five-0 Local Late Show Letterman Late KSNK/NBC America's Got Talent Law Order: CI Harry's Law Local Tonight Show w/Leno Late FOX Hell's Kitchen MasterChef Local Cable Channels A&E Hoarders Hoarders Intervention Intervention Hoarders AMC The Godfather The Godfather ANIM I Shouldn't Be Alive I Shouldn't Be Alive Hostage in Paradise I Shouldn't Be Alive I Shouldn't Be Alive CNN In the Arena Piers Morgan Tonight Anderson Cooper 360 To Be Announced Piers Morgan Tonight DISC Jaws of the Pacific Rogue Sharks Summer of the Shark Rogue Sharks Summer of the Shark DISN Good Luck Shake It Bolt Phineas Phineas Wizards Wizards E! Sex-City Sex-City Ice-Coco Ice-Coco True Hollywood Story Chelsea E! News Chelsea Norton TV ESPN MLB Baseball Baseball Tonight SportsCenter Baseball NFL Live ESPN2 SportsNation Soccer World, Poker World, Poker FAM Secret-Teen Switched at Birth Secret-Teen The 700 Club My Wife My Wife FX Earth Stood Earth Stood HGTV House Hunters Design Star High Low Hunters House House Design Star HIST Pawn Pawn American Pickers Pawn Pawn Top Gear Pawn Pawn LIFE Craigslist Killer The Protector The Protector Chris How I Met Listings: MTV True Life MTV Special Teen Wolf Teen Wolf Awkward.