Languages: the Next Generation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fitzalan High School Ysgol Uwchradd Fitzalan

Fitzalan High School Ysgol Uwchradd Fitzalan ANNUAL GOVERNORS’ REPORT TO PARENTS 2014/2015 Letter from the Chair of Governors Fitzalan High School I take this opportunity to thank you for your support and look forward to Lawrenny Avenue another successful year for Fitzalan. Cardiff Fitzalan pupils have continued to buck national trends by improving their A2 CF11 8XB and AS results for the 4th year running. Over 92% of year 13 students secured 2 or more A* - E grades with pleasing results achieved at AS. The school is particularly delighted that their first ever Oxbridge applicant, Tel No: 029 2023 2850 Mohamed Eghleilib has secured his place at Pembroke College, Oxford to Fax: 029 2087 7800 study medicine by achieving an outstanding 4 A* grades in Maths, Biology, Chemistry, Arabic and Welsh Baccalaureate (WBQ). E-mail: [email protected] Notable other successes were Head girl Laila Nazzal who achieved an A* in History and As in English, Psychology and WBQ as well as an A grade in AS Polish. She will now study International relations at Cardiff University. Andrew Boczek secured an A* in Biology as well as A grades in Chemistry, Maths and WBQ. Amongst the highest achievers at AS were Connie Wu who achieved an impressive 4 A grades along with Raihan Azad and Livvy Forrest who both secured 3 A grades. Fitzalan pupils have continued to excel with over 83% achieving 5 A*-C grades. All the hard work has paid off and staff and students are delighted with the results of their efforts. Over a dozen pupils secured 8 or more A*s with our top boy Jack Cicero obtaining an impressive 12 A*s and our top girl Asia Dirie achieving 10 A*s. -

My Ref: NJM/LS Your Ref

Your Ref: FOI 02146 Dear Mr McEvoy, Thank you for your request under the Freedom of Information Act 2000 about school governors, received on 13/07/12. Your Request asked for: Can you list governors in all primary and secondary schools in the LEA? Can you list all county and community councillors and the governing bodies on which they serve? Can you list the Chair of governors for all primary and secondary schools in the LEA? Can you give the total spend on supply teaching agency staff in the LEA, specifying schools and specifying how much goes to each agency from each school? We have considered your request and enclose the following information: Attached excel files containing information requested. With regards to the information supplied on agency spend, we cannot break the figures down by agency as Cardiff Council has no recorded information relating to chequebook schools and the agencies they may use, as they hold their own financial information. You can contact them directly for further details. If you have any queries or concerns, are in any way dissatisfied with the handling of your request please do not hesitate to contact us. If you believe that the information supplied does not answer your enquiry or if you feel we have not fully understood your request, you have the right to ask for an independent review of our response. If you wish to ask for an Internal Review please set out in writing your reasons and send to the Operational Manager, Improvement & Information, whose address is available at the bottom of this letter. -

Television Journalism Awards

T E L E V I S I O N J O U R N A L I S M A W A R D S Camera Operator of the Year Mehran Bozorgnia - Channel 4 News ITN for Channel 4 Darren Conway - BBC Ten O'clock News/BBC Six O'clock News BBC News for BBC One Arnold Temple - Africa Journal Reuters Television Current Affairs - Home The Drug Trial That Went Wrong - Dispatches In Focus Productions for Channel 4 Exposed - The Bail Hostel Scandal - Panorama BBC Current Affairs for BBC One Prescription for Danger - Tonight with Trevor McDonald ITV Productions for ITV1 Current Affairs - International Iraq - The Death Squads Quicksilver Media Productions for Channel 4 Iraq's Missing Billions - Dispatches Guardian Films for Channel 4 Killer's Paradise - This World BBC Current Affairs for BBC Two Innovation and Multimedia Live Court Stenography Sky News Justin Rowlatt - Newsnight's 'Ethical Man' BBC News for BBC Two War Torn - Stories of Separation - Dispatches David Modell Productions for Channel 4 Nations and Regions Current Affairs Award Facing The Past - Spotlight BBC Northern Ireland Parking - Inside Out (BBC North East and Cumbria) BBC Newcastle Stammer - Inside Out East BBC East Nations and Regions News Coverage Award Aberfan - BBC Wales Today BBC Wales The Morecambe Bay Cockling Tragedy - A Special Edition of Granada Reports ITV Granada Scotland Today STV News - Home Assisted Suicide - BBC Ten O'clock News BBC News for BBC One Drugs - BBC Six O'clock News BBC News for BBC One Selly Oak - A Soldier's Story - ITV Evening News ITN for ITV News News - International Afghanistan Patrol - BBC -

Has TV Eaten Itself? RTS STUDENT TELEVISION AWARDS 2014 5 JUNE 1:00Pm BFI Southbank, London SE1 8XT

May 2015 Has TV eaten itself? RTS STUDENT TELEVISION AWARDS 2014 5 JUNE 1:00pm BFI Southbank, London SE1 8XT Hosted by Romesh Ranganathan. Nominated films and highlights of the awards ceremony will be broadcast by Sky www.rts.org.uk Journal of The Royal Television Society May 2015 l Volume 52/5 From the CEO The general election are 16-18 September. I am very proud I’d like to thank everyone who has dominated the to say that we have assembled a made the recent, sold-out RTS Futures national news agenda world-class line-up of speakers. evening, “I made it in… digital”, such a for much of the year. They include: Michael Lombardo, success. A full report starts on page 23. This month, the RTS President of Programming at HBO; Are you a fan of Episodes, Googlebox hosts a debate in Sharon White, CEO of Ofcom; David or W1A? Well, who isn’t? This month’s which two of televi- Abraham, CEO at Channel 4; Viacom cover story by Stefan Stern takes a sion’s most experienced anchor men President and CEO Philippe Dauman; perceptive look at how television give an insider’s view of what really Josh Sapan, President and CEO of can’t stop making TV about TV. It’s happened in the political arena. AMC Networks; and David Zaslav, a must-read. Jeremy Paxman and Alastair Stew- President and CEO of Discovery So, too, is Richard Sambrook’s TV art are in conversation with Steve Communications. Diary, which provides some incisive Hewlett at a not-to-be missed Leg- Next month sees the 20th RTS and timely analysis of the election ends’ Lunch on 19 May. -

Jo Drake Hair & Make-Up Artist

Jo Drake Hair & Make-Up Artist Television/Film/Photographic 07803 501983 www.jodrake.co.uk [email protected] I am highly experienced and qualified broadcast, film and photographic make- up artist based in London having worked extensively for major UK broadcasters and production companies including ITV, BBC, Channel 4, Sky, Hat Trick, ITN and Flame Television. I’ve covered all genres including news, entertainment, ob docs, scripted reality, sport, current affairs and live events. Television Credits (Selected) xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx Charles at 70 Nov 2018 BBC Studios/BBC1 Documentary of the life of Prince Charles as he turns 70. Harry and Meghan: A Royal Engagement Nov 2017 Renegade Pictures/BBC1 Documentary presented by Kirsty Young about the royals Elizabeth & Philip: Love and Duty July – Sept 2017 BBC Studios/BBC Documentary presented by Kirsty Young for BBC1 World War One Remembered: Passchendaele July 2017 BBC Studios/BBC1 Show presented by Dan Snow and Kirtsy Young covering the commemorations of the Battle of Passchendaele in Belgium. John Bishop In Conversation With April 2016 BBC Studios/BBC1 Prime time series with John Bishop interviewing guests Her Majesty the Queens 90th Birthday. June 2016 Lola Entertainment/BBC1 Live coverage celebrating the queen’s 90 birthday presented by Kirsty Young BBC History Quiz: The Tudors. Sept 2015 BBC Studios/BBC2 Make up designer for the guests Attenborough At 90 Sept 2015 BBC Studios/BBC1 Celebration of David Attenborough career presented by Kirsty Young Battle of Britain 75th Anniversary service at Westminster Abbey Sept 2015 BBC Studios/BBC1 Live broadcast of from Westminster Abbey presented by Dan Snow and Kirsty Young The Festival of Quilts Exhibition & The Knitting & Stitching Show Aug 2014 Create & Craft TV Live show presented from the NEC Unbelievable Moments Caught on Camera Dec 2014 Celebro Studios/ITV1 Page 1 Series presented by Alistair Stewart Made in Chelsea 2013 - 2014 Monkey Kingdom Productions/ITV Make-up & hair designer for the cast. -

PICTURE QUIZ ANSWERS 1 Ringo Starr 41 Roy Orbison 81 Janet Jackson 2 Marie Osmond 42Vincent Price 82 Daniel O Donnell 3 Kenney E

PICTURE QUIZ ANSWERS 1 Ringo Starr 41 Roy Orbison 81 Janet Jackson 2 Marie Osmond 42Vincent Price 82 Daniel o Donnell 3 Kenney Everett 43 Tutter 83 Eddie Izzard 4 David Walliams 44 Whoopi Goldberg 84Barry White 5 Nicolas Cage 45 Orson Wells 85 Sacha Distel 6 Ingrid Bergman 46 Johnny Cash 86 Barbra Streisand 7 Dustin Hoffman 47 Vincent Van Gough 87 Peter Kay 8Jim Bowen 48 Mike 88 Julie Andrews 9 Shirley Temple 49 Britney Spears 89 Gene Pitney 10 Fats Domino 50 Rowan Akinson 90 Charlotte Church 11 Norman Wisdom 51 Su Pollard 91 Amanda Redman 12 Norman Collier 52 Shirley Crabtree 92 Nina Simone 13 Lester Piggott 53 Sammy Davis Jnr 93 Ray Reardon 14 Nigella Lawson 54 Little Weed 94 Christina Aguilera 15 Placido Domingo 55 Bette Midler 95 Bonnie Tyler 16 Gok Wan 56 Thora Hird 96 Peter Cushing 17 Angela Lansbury 57 Kathy Staff 97 Bobby Vee 18 Trevor McDonald 58 Gary Newman 98 Amanda Holden 19 Sid James 59 Bill Cosby 99 Tom Jones 20 Megan Markle 60 Ina Garten 100 Dr Hillary Jones 21 Bamber Gascoigne 61 Benny Hill 101 Jerry Lee Lewis 22 Sandra Bullock 62 Michael Schumacher 102 Omar Sharif 23 Harry Enfield 63 Steve Davis 103 Bruno Sanmartino 24 Andy Williams 64 Sally Gunnell 104 Neil Morrissey 25 Dusty Springfield 65 Johnny Depp 105 Timon 26 Robbie Williams 66 Elizabeth Taylor 106 Jimmy Hendrix 27 Vera Lynne 67 J.K.Rowling 107 Patsy Cline 28 Julian Clary 68 Alexandra Burke 108 Simon Cowell 29 Boris Karloff 69 Danny Dyer 109 Derrick Evans 30 Bruce Lee 70 Princess Eugenie 110 Val Doonican 31 Nana Mouskouri 71 John Thaw 111 Barry Hawkins 32 Paloma Faith 72 Boris Johnson 112 Margaret Rutherford 33 Virginia McKenna 73 Len Goodman 113 Upsy Daisy 34 Alan Wicker 74 Marlon Brando 114 Stephanie Powers 35 Elaine Paige 75 Ozzy Osbourne 115 John Cena 36 Susan Boyle 76 Karl Malden 116 Leslie Grantham 37 Daniel Craig 77 Tara Palmer Tomkinson 117 Michael Barrymore 38 Dusty Bin 78 Looby Loo 118 Judy Garland 39 Dale Winton 79 Anita Harris 119 Demi Moore 40 Oliver Hardy 80 Marcus Wareing 120 Shrek . -

Commonwealth Women Parliamentarians

British Islands and Mediterranean Region Commonwealth Women Parliamentarians The National Assembly for Wales is the Content democratically elected body that represents the interests of Wales and its people, Foreword ................................................................................................................5 makes laws for Wales, agrees Welsh taxes Programme ..........................................................................................................9 and holds the Welsh Government to account. Biographies .......................................................................................................19 Speakers .............................................................................................................59 Performers .........................................................................................................71 Conference Management .......................................................................75 CONTACT US 0300 200 6565 [email protected] www.assembly.wales @AssemblyWales © National Assembly for Wales Commission Copyright 2017 The text of this document may be reproduced free of charge in any format or medium providing that it is reproduced accurately and not used in a misleading or derogatory context. The material must be acknowledged as copyright of the National Assembly for Wales Commission and the title of the document specified. 3 Foreword Foreword Foreword Joyce Watson AM BIMR CWP Chair Croeso i Gymru – Welcome to Wales! It is difficult to avoid the B-word, -

Newsletter Dec 2016

Brynmawr Foundation School DecemberBrynmawr 2016 Newsletter Foundation School Ysgol Sylfaenol Brynmawr December 2016 Newsletter Dear Parent, Time this year has flown by but the year so far has been packed full of achievements born from the efforts of our students, staff and school community. Every day I continue to be inspired by the students and my colleagues and all that they do together to make Brynmawr Foundation School special, unique and outstanding. All the activities and achievements since September continue to highlight how impressive our students are and the energy, talent, enthusiasm and commitment they bring to our school, Dates for your Diary illustrating the continued dedication of all our staff I am proud of the commitment our students have shown in December representing their school when on trips and also at events in 15th – End of Term the school. 16th – INSET Day For some families, of course, Christmas does not bring the joy January and happiness with which others are so blessed. With this in 3rd – Start of Spring Term mind I am extremely proud of our pupils and their efforts in 19th – Year 9/10 Options Evening raising money for charity including, once again, a significant th amount of money to buy presents for the Barnardo’s appeal. 25 – 6pm Year 11 Prom Catwalk Show Our focus in January continues to be student progress and ensuring that students are positively engaged with their February learnin g. We have had over 200 applicants for a maximum 151 7th – 9th School Production entry in September 2017. Staff have maintained incredibly 15th – Year 11 Parents Evening high standards as a team, so that all functions of the school 16th – 20th Florida Trip are focused on supporting the students’ learning and progress. -

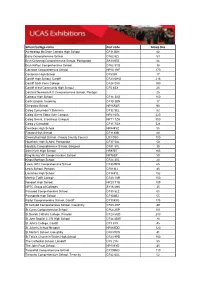

School/College Name Post Code Group Size

School/college name Post code Group Size Archbishop McGrath Catholic High School CF312DN 82 Barry Comprehensive School CF62 8ZJ 53 Bryn Celynnog Comprehensive School, Pontypridd SA131ES 84 Bryn Hafren Comprehensive School CF62 9YQ 38 Caerleon Comprehensive School NP18 1NF 170 Cantonian High School CF53JR 17 Cardiff High School, Cardiff CF23 6WG 216 Cardiff Sixth Form College CF24 0AA 190 Cardiff West Community High School CF5 4SX 25 Cardinal Newman R C Comprehensive School, Pontypri 25 Cathays High School CF14 3XG 160 Celtic English Academy CF10 3BN 17 Chepstow School NP16RLR 90 Coleg Cymunedol Y Dderwen CF32 9EL 82 Coleg Gwent Ebbw Vale Campus NP23 6GL 220 Coleg Gwent, Crosskeys Campus NP11 7ZA 500 Coleg y Cymoedd CF15 7QX 524 Cwmbran High School NP444YZ 55 Fitzalan High School CF118XB 80 Gwernyfed High School - Powys County Council LD3 0SG 100 Hawthorn High School, Pontypridd CF37 5AL 50 Heolddu Comprehensive School, Bargoed CF81 8XL 30 John Kyrle High School HR97ET 165 King Henry VIII Comprehensive School NP76EP 50 Kings Monkton School CF24 3XL 20 Lewis Girls' Comprehensive School CF381RW 65 Lewis School, Pengam CF818LJ 45 Llanishen High School CF145YL 152 Merthyr Tydfil College CF48 1AR 150 Newport High School NP20 7YB 109 NPTC Group of Colleges SY16 4HU 35 Pencoed Comprehensive School CF35 5LZ 65 Pontypridd High School CF104BJ 55 Radyr Comprehensive School, Cardiff CF158XG 175 St Cenydd Comprehensive School, Caerphilly CF83 2RP 49 St Cyres Comprehensive School CF64 2XP 101 St Davids Catholic College, Penylan CF23 5QD 200 St John Baptist -

Andrea-Levy-Special-Issue-FINAL.Pdf

ENTERTEXT Special Issue on Andrea Levy Issue 9, 2012 Guest Editor: Wendy Knepper In memory of Cosmo (1993-2010) A cat who lived happily in Toronto, Berlin, and London ‘I’ve never seen him so upset. He really loves that cat. He’s going to miss her. He said he’d never have another one because you just get attached to them and they die. I think she’s dead, Ange–went somewhere to die. But I didn’t say that to yer dad. He’s too upset. He loves that cat. I hope he finds her.’ —Andrea Levy, Never Far from Nowhere Table of Contents Introduction: Andrea Levy’s Dislocating Narratives 1 Wendy Knepper The Familiar Made Strange: The Relationship between the Home and Identity in 14 Andrea Levy’s Fiction Jo Pready Crossing Over: Postmemory and the Postcolonial Imaginary in Andrea Levy’s 31 Small Island and Fruit of the Lemon Claudia Marquis “Telling Her a Story”: Remembering Trauma in Andrea Levy’s Writing 53 Ole Laursen Identity as Cultural Production in Andrea Levy’s Small Island 69 Alicia E. Ellis Women Writers and the Windrush Generation: A Contextual Reading of Beryl 84 Gilroy’s In Praise of Love and Children and Andrea Levy’s Small Island Sandra Courtman Representations of Ageing and Black British Identity in Andrea Levy’s Every Light 105 in the House Burnin’ and Joan Riley’s Waiting in the Twilight Charlotte Beyer Stranger in the Empire: Language and Identity in the ‘Mother Country’ 122 Ann Murphy A Written Song: Andrea Levy’s Neo-Slave Narrative 135 Maria Helena Lima Coloured 154 Mohanalakshmi Rajakumar Letter to Motherwell 162 Rhona Hammond Contributors 169 Andrea Levy’s Dislocating Narratives1 Wendy Knepper This special issue on Andrea Levy (1956- ), the first of its kind, considers the author’s contribution to contemporary literature by exploring how her narratives represent the politics of place2 as well as the dislocations associated with empire, migration, and social transformation. -

Why Expand and Replace Cantonian High School?

Contents Introduction • What is this booklet about? • Background • What are we proposing to do? Consultation • How can you find out more and let us know your views? • Your views are important to us Explanation of terms used in this document Background Why are we proposing these changes? • The provision of school places • Condition & Suitability • What is the Band B 21st Century Schools Programme? Community Secondary School Places • Demand for Places • Autism Spectrum Condition (ASC) Provision • Special School Places Why expand and replace Cantonian High School? • Schools serving the area at present • Demand for places • Condition & Suitability Why expand the Specialist Resource Base (SRB)? Why expand Riverbank Special School and Woodlands High School? Why move these schools? • The provision of special school places • Why move Riverbank Special School and Woodlands High School to the Cantonian High School site? • Condition & Suitability How would other schools be affected? Facilities included in a school Site Plan Quality and Standards • Estyn • Welsh Government categorisation of schools • Cantonian High School • Riverbank Special School • Woodlands High School How would standards in school be affected by the changes? • Standards • Teaching and learning experience • Care support and guidance • Leadership and management How would nursery provision be affected? 21st Century Schools Century 21st School, High Cantonian of The redevelopment School High Woodlands School and Special Riverbank How would Post 16 provision be affected? • Cantonian -

21St Century Schools Consultation Document 2021 the EXPANSION and REDEVELOPMENT of CATHAYS HIGH SCHOOL

21st Century Schools Consultation Document 2021 THE EXPANSION AND REDEVELOPMENT OF CATHAYS HIGH SCHOOL 29 January - 19 March 2021 This document can be made available in Braille. A summary version of this document is available at www.cardiff.gov.uk/cathayshighproposals Information can also be made available in other community languages if needed. Please contact us on 029 2087 2720 to arrange this Contents Introduction • What is this booklet about? • Background • What are we proposing to do? Consultation • Views of children on the proposed changes • How can you find out more and let us know your views? • Your views are important to us Explanation of terms used in this document What is the Band B 21st Century Schools Programme? • The provision of school places • Condition & Suitability Schools serving the Cathays High School catchment area Why expand and replace Cathays High School? • Demand for places city-wide • Demand for places in the Cathays High School catchment area and neighbouring areas • Cathays High School Condition & Suitability Autistic Spectrum Condition (ASC) Provision • Why expand the Specialist Resource Base (SRB)? How would Post 16 Provision be affected? Land Matters including improving community facilities Facilities included in a school Site Map Quality and Standards • Estyn • Welsh Government categorisation of schools • Cathays High School How would standards be affected by the changes? • Standards • Teaching and learning experiences • Care support and guidance • Leadership and management Additional Support for pupils